Art and Peformance in Mali Stephen Wooten

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine; ff^VoS SISIB Anglo American Corporation Services Limited T1HTO The Rio Tinto Foundation APEXAPEZCOBTCOBPOBATION OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht ^RISTON ^.Tanganda Tea Company Limited A-"^" * ETWORK •yvcoDBultaots NDORO Contents March 1997 Artnotes : the AICA conference on Art Criticism & Africa Burning fires or slumbering embers? : ceramics in Zimbabwe by Jack Bennett The perceptive eye and disciplined hand : Richard Witikani by Barbara Murray 11 Confronting complexity and contradiction : the 1996 Heritage Exhibition by Anthony Chennells 16 Painting the essence : the harmony and equilibrium of Thakor Patel by Barbara Murray 20 Reviews of recent work and forthcoming exhibitions and events including: Earth. Water, Fire: recent work by Berry Bickle, by Helen Lieros 10th Annual VAAB Exhibition, by Busani Bafana Explorations - Transformations, by Stanley Kurombo Robert Paul a book review by Anthony Chennells Cover: Tendai Gumbo, vessel, 1995, 25 x 20cm, terracotta, coiled and pit-fired (photo credit: Jack Bennett & Barbara Murray) Left: Crispen Matekenya, Baboon Chair, 1996, 160 x 1 10 x 80cm, wood © Gallery Publications Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Design & typesetting: Myrtle Mollis. Originaiion: HPP Studios. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Paper: Magno from Graphtec Lid. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta, the publisher or the editor Articles are invited for submission. -

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: APEX CDRPORATIDN OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht NDORO ^RISTON Contents December 1998 2 Artnotes 3 New forms for old : Dak" Art 1998 by Derek Huggins 10 Charting interior and exterior landscapes : Hilary Kashiri's recent paintings by Gillian Wright 16 'A Changed World" : the British Council's sculpture exhibition by Margaret Garlake 21 Anthills, moths, drawing by Toni Crabb 24 Fasoni Sibanda : a tribute 25 Forthcoming events and exhibitions Front Cover: TiehenaDagnogo, Mossi Km, 1997, 170 x 104cm, mixed media Back Cover: Tiebena Dagnogo. Porte Celeste, 1997, 156 x 85cm, mixed media Left: Tapfuma Gutsa. /// Winds. 1996-7, 160 x 50 x 62cm, serpentine, bone & horn © Gallery Publications ISSN 1361 - 1574 Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Designer: Myrtle Mallis. Origination: Crystal Graphics. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta. Gallery Publications, the publisher or the editor Articles and Letters are invited for submission. Please address them to The Editor Subscriptions from Gallery Publications, c/o Gallery Delta. 110 Livingstone Avenue, P.O. Box UA 373. Union Avenue, Harare. Zimbabwe. Tel & Fa.x: (263-4) 792135, e-mail: <[email protected]> Artnotes A surprising fact: Zimbabwean artworks are Hivos give support to many areas of And now, thanks to Hivos. -

Structure and Meaning in the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe

STRUCTURE AND MEANING IN THE PREHISTORIC ART OF ZIMBABWE PETER S. GARLAKE Seventeenth Annual Mans Wolff Memorial Lecture April 15, 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana Copyright 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University All rights reserved ISBN 0-941934-51-9 PETER S. GARLAKE Peter S. Garlake is an archaeologist and the author of many books on Africa. He has conducted fieldwork in Somalia, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Qatar, the Comoro Islands and Mozambique, and has directed excavations at numerous sites in Zimbabwe. He was the Senior Inspector of Monuments in Rhodesia from 1964 to 1970, and a senior research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ife from 1971 to 1973. From 1975 to 1981, he was a lecturer in African archaeology and material culture at the Department of Anthropology, University College, University of London. F.rom 1981 to 1985, he was attached to the Ministry of Education and Culture in Zimbabwe and in 1984-1985 was a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Zimbabwe. For the past year, he has been conducting full time research on the prehistoric rock art of Zimbabwe. He is the author of Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast, 1966; Great Zimbabwe, 1973; The Kingdoms of Africa, 1978; Great Zimbabwe Described and Exglained, 1982; Life qt Great Zimbabwe, 1982; People Making History, 1985; and is currently writing The Painted Caves. Peter Garlake is a contributor to the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archaeology, the hpggqn ---Encyclopedia --- ---- of Africa and the MacMillan Dictionary of big, and is the author of many journal and newspaper articles. -

Zimbabwe Mobilizes ICAC’S Shift from Coup De Grâce to Cultural Coup

dialogue Zimbabwe Mobilizes ICAC’s Shift from Coup de Grâce to Cultural Coup Ruth Simbao, Raphael Chikukwa, Jimmy Ogonga, Berry Bickle, Marie Hélène Pereira, Dulcie Abrahams Altass, Mhoze Chikowero, and N’Goné Fall To whom does Africa belong? Whose Africa are we talking about? … R S is a Professor of Art History and Visual Culture and It’s time we control our narrative, and contemporary art is a medium the National Research Foundation/Department of Science and Tech- that can lead us to do this. nology SARChI Chair in the Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa in the National Gallery of Zimbabwe () Fine Art Department at Rhodes University, South Africa. r.simbao@ ru.ac.za Especially aer having taken Zimbabwe to Venice, we needed to bring R C is the Chief Curator at the National Gallery of the world to Zimbabwe to understand the context we are working in. Zimbabwe in Harare, and has been instrumental in establishing the Raphael Chikukwa (Zvomuya b) Zimbabwe Platform at the Venice Biennale. J O is an artist and producer based in Malindi, Kenya. he International Conference on African Cultures His work interweaves between artistic practice and curatorial strate- (ICAC) was held at the National Gallery of gies, and his curatorial projects include e Mombasa Billboard Proj- Zimbabwe in Harare from September –, ect (2002, Mombasa), and Amnesia (2006-2009, Nairobi). In 2001, . Eight delegates write their reections on he founded Nairobi Arts Trust/Centre of Contemporary Art, Nairobi (CCAEA), an organization that works as a catalyst for the visual arts the importance of this Africa-based event. -

Following the Stone: Zimbabwean Sculptors Carving a Place in 21St Century Art Worlds

FOLLOWING THE STONE: ZIMBABWEAN SCULPTORS CARVING A PLACE IN 21ST CENTURY ART WORLDS BY LANCE L. LARKIN DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology with a minor in African Studies with a minor in Museum Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2014 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Alma Gottlieb, Chair Professor Matti Bunzl Associate Professor Theresa Barnes Krannert Art Museum Curator Allyson Purpura ABSTRACT This dissertation follows the historical trajectory of the products of Zimbabwean stone sculptors to examine the interplay between international art markets and the agency of the artists themselves. Although this 1960s arts movement gained recognition within global art circuits during the colonial era – and greater acclaim following independence – by the turn of the 21st century only a few sculptors were able to maintain international success. Following the depreciation on the markets, I ask: (1) for what reasons do international art buyers now devalue Zimbabwean stone sculpture after having valorized it in the 1960s-80s? (2) How do Zimbabwean artists react to these vicissitudes of the international art markets? In the first half of the dissertation I examine how the stone sculpture was framed by European patrons as a Modernist art that valorized indigenous beliefs in contrast to the Rhodesian colonial regime’s oppression. Following independence in 1980, the movement continued to be framed as a link to pre-state carving traditions – solidifying links with “tradition” – while the political economic situation in Zimbabwe began to deteriorate by the end of the 1990s. -

Attwell Mamvuto D. Phil 2013 1 .Pdf

VISUAL EXPRESSION AMONG CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS: IMPLICATIONS FOR ART EDUCATION BY ATTWELL MAMVUTO A THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF TEACHER EDUCATION FACULTY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF ZIMBABWE 2013 i Dedication To my family and uncle Davies who have always been a source of inspiration. ii Acknowledgements I would like to extend my sincere appreciation to all contemporary artists, Chikonzero Chazunguza (Chiko), David Chinyama, Charles Kamangwana, Doris Kampira and Chenjerai Mutasa, who granted me the chance to interview and observe them as they worked in their ateliers, and provided artworks for analyses. It was through an analysis of their practice that I gained valuable insights into contemporary visual practice in Zimbabwe. Their co-operation and contribution is greatly appreciated. I am also grateful to colleges and art lecturers, schools and art teachers for the provision of documents for analyses as well as interviews and discussions. The documents were insightful and informative as they contained the much needed data on the implementation of art curricula at various levels of education. Thank you for the valuable information and candid views that made my understanding of current art education in Zimbabwe more informed. Great thanks go to Mr and Mrs Chawatama for the efficient and reliable audio tape recorder that was used in the study. It made the transcription process an easier task than I thought as all the interviews were clear and audible. I am greatly indebted to my supervisors: Dr Natsa, Professor Zindi and Dr Matiure, for their invaluable guidance throughout the entire study. -

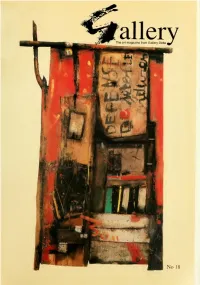

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: \t ify(fi /Siti, TINTC The RioTinto Foundation APEX COMCORPORATION OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht nETWORK NDORO IHt Commonwealth lOUNDATION Ai I IV (^ A- allery Contents September 1997 Luis Meque ; painting Zimbabwean darkness by Barbara Murray Namibia — a new creative mood by Laura Henderson An opening window in Bulawayo — Yvonne Vera : an interview witii Godfrey Moyo Contemporary maskings — Bulelwa Madekurozwa and Tendai Gumbo by Doreen Sibanda Looking from afar : a collectt)r's view by Gianni Baiocchi Throw a six and go to Venice by Margaret Garlake Bernard Takawira — a tribute by Roy Guthrie Forthcoming events and exhibitions Cover: Luis Meque, City Boys (with details on back cover). 1997. 90 X 99cm. mixed media. Photo: Barbara Murray Left: Keston Beaton. Acoustics, 1997, 127 x 35 x 1 1cm. found objects © Gallery Publications Publisher: Derek Huggiiis. Editor: Barbara Murray. Design & Layout: Myrtle Mallis. Origination: HPP Studios. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta, the publisher or the editor. Articles are invited for submission. Please address them to The Editor Subscriptions Irom Gallery Publications, c/o Gallery Delta. 1 10 Livingstone Avenue, P.O. Box UA 37.^. Union Avenue. Harare. Zimbabwe. Tel & Fax: (26.3-4)792135 e-mail: [email protected] Luis Meque is now fairly widely recognised as one of Zimbabwe's most talented artists. -

Crafts and Visual Arts

SEED WORKING PAPER No. 51 Series on Upgrading in Small Enterprise Clusters and Global Value Chains Promoting the Culture Sector through Job Creation and Small Enterprise Development in SADC Countries: Crafts and Visual Arts by The Trinity Session InFocus Programme on Boosting Employment through Small EnterprisE Development Job Creation and Enterprise Department International Labour Office · Geneva Copyright © International Labour Organization 2003 First published 2003 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; e-mail: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; e-mail: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ILO Promoting the Culture Sector through Job Creation and Small Enterprise Development in SADC Countries: Crafts and Visual Arts Geneva, International Labour Office, 2003 ISBN 92-2-115418-1 The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Rock Art Incorporated: an Archaeological and Interdisciplinary Study of Certain Human Figures in San Art

ROCK ART INCORPORATED: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDY OF CERTAIN HUMAN FIGURES IN SAN ART Anne Solomon Town Cape of Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of Cape Town UniversityAugust 1995 #·-:-•.. ~ ,r::,,_,,_--·I The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the Universityof of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University Abstract Rock art incorporated: an archaeological and interdisciplinary study of certain human figures in San art. Anne Solomon Department of Archaeology, University of Cape Town August 1995 Understanding a widespread motif in San rock art - a human figure depicted in frontal perspective with distinctive bodily characteristics - is the aim of this study. A concentration of these figures in north eastern Zimbabwe was first described by researchers in the 1930s and subsequently, when one researcher, Elizabeth Goodall, described them as 'mythic women'. Markedly similar figures in the South African art have receiyed little attention. On the basis of fieldwork in the KwaZulu-Natal Drakensberg, the south western Cape (South Africa) and Zimbabwe, and an extensive literature survey, a spectrum of these figures is described. In order to further understanding of the motif, existing interpretive methods and the traditions which inform them are examined, with a view to outlining a number of areas in need of attention. -

Educational Change and Cultural Politics: National Identity- Formation in Zimbabwe

EDUCATIONAL CHANGE AND CULTURAL POLITICS: NATIONAL IDENTITY- FORMATION IN ZIMBABWE A Dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Education of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Douglas Mpondi March 2004 This dissertation entitled EDUCATIONAL CHANGE AND CULTURAL POLITICS: NATIONAL IDENTITY- FORMATION IN ZIMBABWE BY DOUGLAS MPONDI has been approved for the Department of Educational Studies and the College of Education by W.S. Howard Professor of Educational Studies James Heap Dean, College of Education, Ohio University Abstract MPONDI, DOUGLAS PH.D March 2004. Cultural Studies Educational change and cultural politics: national identity-formation in Zimbabwe (240pages) Director of Dissertation: Stephen Howard The study investigates how the post-independent government of Zimbabwe, as seen through the lens of its cultural critics, used the institution of education as a focal point for nation-building and social transformation. The project examines how critics respond to the use of educational change as a way of political legitimization. Whilst a number of scholars have focused on post-colonial Zimbabwe during the post-1980 period, they did not have the chance to study it during the post-2000 era, which was a critical and dramatic historical juncture because of the turmoil and a reversal trend of the promises that were made at independence. The qualitative research approach was formulated to collect data on education and language policy, politics and culture from a cross-section of people of the Zimbabwean society. Brief case study interviews were conducted to provide newer and richer details on Zimbabwean cultural landscape. -

Shona Sculpture'

The African e-Journals Project has digitized full text of articles of eleven social science and humanities journals. This item is from the digital archive maintained by Michigan State University Library. Find more at: http://digital.lib.msu.edu/projects/africanjournals/ Available through a partnership with Scroll down to read the article. Zambezia (1993), XX (H). THE MYTH OF 'SHONA SCULPTURE' CAROLE PEARCE Abstract 'Shona sculpture' has always relied heavily for its commercial success on its supposed authenticity and autonomy. However, the genre is neither rooted in the spontaneous expression of traditional Black spirituality, nor is it an autonomous contemporary Black art form. The sculpture is easily explained as a deliberate product of the modernist tastes of White expatriates during the 1950s and 1960s and, in particular, those of the first Director of the National Gallery. THIS ARTICLE ARISES from reflections on the way in which, over time, views originally thought to be daringly radical and avant-garde become incorporated into the general stream of thought. Here their brilliant lustre fades and they congeal into the solid rock of the commonplace. The myth of 'Shona sculpture' is an illustration of this process. Thirty years ago the notion of a serious, non-functional and non- ritualistic contemporary Black art would have been given little popular credence. During that time, however, 'Shona sculpture' has earned itself a secure niche in the art galleries and markets of the developed world and is collected on a large scale, exported by the tonne by galleries and private dealers, exhibited in universities, museums, galleries and parks in the West and is the subject of numerous journal articles and a few monographs. -

The Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe The publisher and editor gratefully acknowledge the following who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: APEX CORFDRATION OF ZIMBABWE LIMITEB Joerg Sorgenicht ft j/M © Gallery Publications Contents March 2000 ISSN 1561 -1574 Publislner: Derel^ Muggins Editor: Barbara Murray Designer: Myrtle Mallis Animating the image : a video art project by Barbara Murray Origination: Crystal Graptiics Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co 11 Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be Advances and retreats : the study of rock painting in Zimbabwe reproduced in any manner or form by Peter Garlake without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves 17 and not necessahly those of Gallery Delta. Gallery Publications, the Painting = Present by Jerry Zeniiik Publisher or the Editor. Cover: Berry Bickle, Age of Iron I & // and Articles and Letters are invited for video stills, 1999, 21 submission. Please address them mixed media to the Editor. Missing the object : still-life painting in the Zimbabwean context by Frances above: Paul Wade, Marks Subscriptions from Gallery millenium, 1999, Publications, c/o Gallery Delta, 1 1 Livingstone Avenue, 113 X 135 X 11cm, P.O. Box UA 373. Union Avenue. mixed media 25 Harare. Zimbabwe. Forthcoming events photo credit: David and exhibitions Tel & Fax: (263-4)792135 Brazier E-mail: <[email protected]> Animating tlie image Barbara Murray writes about an experimental project that introduced a new medium to the Zimbabwean art scene Searching for ever 'better' means of expressing ideas was the 'new' communication technology but it was and communicating more effectively with society is institution-based, expensive, largely commercial and part of the artist's role.