Rock Art Incorporated: an Archaeological and Interdisciplinary Study of Certain Human Figures in San Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehistoric Art: Their Contribution for Understanding on Prehistoric Society

Prehistoric Art: Their Contribution for Understanding on Prehistoric Society Sofwan Noerwidi Balai Arkeologi Yogyakarta The pictures indicated as an art began their human invasion of the symbolic world, just started around 100.000 BP and more intensively since 30.000 years. The meaning of the relations between the men and with their world is produced by organization of representations in graphic systems by images, expression and communication in the same time. Since the first appearance of genus Homo, the development of cerebral and social evolution probably causes the ability to symbolize. Human uses the image to the modernity which is gives a symbolic way to the meaning for the beings and to the things (Vialou, 2009). This paper is a short report about development of contribution on study of symbolic behavior for interpreting of prehistoric society, from beginning period until recent times by several scholars. When late nineteenth and early twentieth century scientists have accept that Upper Paleolithic art is being genuinely of great antiquity. At that times, paleolithic art was interpreted merely as “art for art’s sake”. The first systematic study of Ice Age art was undertaken by Abbé Henri Breuil, a great French archeologist. He carefully copied images from a lot of sites and reconstructs a development chronology based on artistic style during the first half of the twentieth century. He believed that the art would grow more complicated through time (Lewin, et.al., 2004). After the beginning study by Breuil, as a summary they are several contributions on study of symbolic behavior for interpreting of prehistoric society, such as for reconstruction of prehistoric religion, social structure of their society, information exchange system between them, and also as indication of cultural and historical change in prehistoric times. -

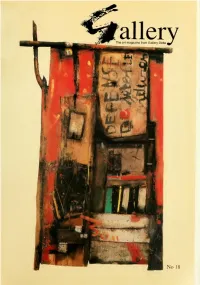

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine; ff^VoS SISIB Anglo American Corporation Services Limited T1HTO The Rio Tinto Foundation APEXAPEZCOBTCOBPOBATION OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht ^RISTON ^.Tanganda Tea Company Limited A-"^" * ETWORK •yvcoDBultaots NDORO Contents March 1997 Artnotes : the AICA conference on Art Criticism & Africa Burning fires or slumbering embers? : ceramics in Zimbabwe by Jack Bennett The perceptive eye and disciplined hand : Richard Witikani by Barbara Murray 11 Confronting complexity and contradiction : the 1996 Heritage Exhibition by Anthony Chennells 16 Painting the essence : the harmony and equilibrium of Thakor Patel by Barbara Murray 20 Reviews of recent work and forthcoming exhibitions and events including: Earth. Water, Fire: recent work by Berry Bickle, by Helen Lieros 10th Annual VAAB Exhibition, by Busani Bafana Explorations - Transformations, by Stanley Kurombo Robert Paul a book review by Anthony Chennells Cover: Tendai Gumbo, vessel, 1995, 25 x 20cm, terracotta, coiled and pit-fired (photo credit: Jack Bennett & Barbara Murray) Left: Crispen Matekenya, Baboon Chair, 1996, 160 x 1 10 x 80cm, wood © Gallery Publications Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Design & typesetting: Myrtle Mollis. Originaiion: HPP Studios. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Paper: Magno from Graphtec Lid. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta, the publisher or the editor Articles are invited for submission. -

Gallery : the Art Magazine from Gallery Delta

Sponsoring art for Zimbabwe Gallery Delta, the publisher and the editor gratefully acknowledge the following sponsors who have contributed to the production of this issue of Gallery magazine: APEX CDRPORATIDN OF ZIMBABWE LIMITED Joerg Sorgenicht NDORO ^RISTON Contents December 1998 2 Artnotes 3 New forms for old : Dak" Art 1998 by Derek Huggins 10 Charting interior and exterior landscapes : Hilary Kashiri's recent paintings by Gillian Wright 16 'A Changed World" : the British Council's sculpture exhibition by Margaret Garlake 21 Anthills, moths, drawing by Toni Crabb 24 Fasoni Sibanda : a tribute 25 Forthcoming events and exhibitions Front Cover: TiehenaDagnogo, Mossi Km, 1997, 170 x 104cm, mixed media Back Cover: Tiebena Dagnogo. Porte Celeste, 1997, 156 x 85cm, mixed media Left: Tapfuma Gutsa. /// Winds. 1996-7, 160 x 50 x 62cm, serpentine, bone & horn © Gallery Publications ISSN 1361 - 1574 Publisher: Derek Huggins. Editor: Barbara Murray. Designer: Myrtle Mallis. Origination: Crystal Graphics. Printing: A.W. Bardwell & Co. Contents are the copyright of Gallery Publications and may not be reproduced in any manner or form without permission. The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the writers themselves and not necessarily those of Gallery Delta. Gallery Publications, the publisher or the editor Articles and Letters are invited for submission. Please address them to The Editor Subscriptions from Gallery Publications, c/o Gallery Delta. 110 Livingstone Avenue, P.O. Box UA 373. Union Avenue, Harare. Zimbabwe. Tel & Fa.x: (263-4) 792135, e-mail: <[email protected]> Artnotes A surprising fact: Zimbabwean artworks are Hivos give support to many areas of And now, thanks to Hivos. -

Art and Symbolism: the Case Of

ON THE EMERGENCE OF ART AND SYMBOLISM: THE CASE OF NEANDERTAL ‘ART’ IN NORTHERN SPAIN by Amy Chase B.A. University of Victoria, 2011 A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2017 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ABSTRACT The idea that Neandertals possessed symbolic and artistic capabilities is highly controversial, as until recently, art creation was thought to have been exclusive to Anatomically Modern Humans. An intense academic debate surrounding Neandertal behavioural and cognitive capacities is fuelled by methodological advancements, archaeological reappraisals, and theoretical shifts. Recent re-dating of prehistoric rock art in Spain, to a time when Neandertals could have been the creators, has further fuelled this debate. This thesis aims to address the underlying causes responsible for this debate and investigate the archaeological signifiers of art and symbolism. I then examine the archaeological record of El Castillo, which contains some of the oldest known cave paintings in Europe, with the objective of establishing possible evidence for symbolic and artistic behaviour in Neandertals. The case of El Castillo is an illustrative example of some of the ideas and concepts that are currently involved in the interpretation of Neandertals’ archaeological record. As the dating of the site layer at El Castillo is problematic, and not all materials were analyzed during this study, the results of this research are rather inconclusive, although some evidence of probable symbolic behaviour in Neandertals at El Castillo is identified and discussed. -

Structure and Meaning in the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe

STRUCTURE AND MEANING IN THE PREHISTORIC ART OF ZIMBABWE PETER S. GARLAKE Seventeenth Annual Mans Wolff Memorial Lecture April 15, 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana Copyright 1987 African Studies Program Indiana University All rights reserved ISBN 0-941934-51-9 PETER S. GARLAKE Peter S. Garlake is an archaeologist and the author of many books on Africa. He has conducted fieldwork in Somalia, Tanzania, Kenya, Nigeria, Qatar, the Comoro Islands and Mozambique, and has directed excavations at numerous sites in Zimbabwe. He was the Senior Inspector of Monuments in Rhodesia from 1964 to 1970, and a senior research fellow at the Institute of African Studies, University of Ife from 1971 to 1973. From 1975 to 1981, he was a lecturer in African archaeology and material culture at the Department of Anthropology, University College, University of London. F.rom 1981 to 1985, he was attached to the Ministry of Education and Culture in Zimbabwe and in 1984-1985 was a lecturer in archaeology at the University of Zimbabwe. For the past year, he has been conducting full time research on the prehistoric rock art of Zimbabwe. He is the author of Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast, 1966; Great Zimbabwe, 1973; The Kingdoms of Africa, 1978; Great Zimbabwe Described and Exglained, 1982; Life qt Great Zimbabwe, 1982; People Making History, 1985; and is currently writing The Painted Caves. Peter Garlake is a contributor to the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Archaeology, the hpggqn ---Encyclopedia --- ---- of Africa and the MacMillan Dictionary of big, and is the author of many journal and newspaper articles. -

Denisovan News: Keeping These Remarkable Yet Enigmatic People up Front by Tom Baldwin

BUSINESSBUSINESS NAMENAME BUSINESSBUSINESS NAMENAME Pleistocene coalition news VOLUME 11, ISSUE 6 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2019 Inside -- ChallengingChallenging thethe tenetstenets ofof mainstreammainstream scientificscientific aagg e e n n d d a a s s -- We at PCN want to thank everyone for making our 10th Anniversary Issue (Issue #61, P A G E 2 September-October 2019) such a success and we thank everyone for writing us. Denisovan news: As most now realize, founding member and central figure of the Pleistocene Coaltiion, Dr. Vir- Keeping these re- markable though ginia Steen-McIntyre’s, recent stroke and other illnesses have become a concern for all those enigmatic people who know her and work Readers were taken by surprise with Tim Holmes’ up front with her as well as for our ‘Paleolithic human dispersals via natural floating readers. The loss of her Tom Baldwin platforms, Part 1 ’ last issue. crucial roles as writer, In contrast to presumed ocean P A G E 4 travel via sailing or paddling scientific advisor, core 10 years ago in PCN manmade watercraft Holmes PCN editor, writer organ- From comparing aerial Dr. Virginia Steen- suggested a third way has izer, etc., while she recov- views of the Middle East with South McIntyre’s first been downplayed in anthro- ers has also added to our A natural pumice raft African cir- In Their Own Words pology and readers re- other editors’ responsibili- cles over column sponded, asking, “Why is this idea not better ties and difficulty in keep- known?” Holmes is still working to finish Part 2. 6,000 miles Virginia Steen-McIntyre ing up. -

The Cradle of Humanity: Prehistoric Art and Culture/ by Georges Bataille : Edited and Introduced by Stum Kendall ; Translated by Michelle Kendall and Stum Kendall

The Cradle of Humanity Prehistoric Art and Culture Georges Bataille Edited and Introduced by Stuart Kendall Translated by Michelle Kendall and Stuart Kendall ZONE BOOKS · NEW YORK 2005 � 2005 UrzoneInc ZONE B001[S 1226 Prospect Avenue Brooklyn, NY 11218 All rights reserved. No pm of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfihning,recording, or otherwise (except for that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright uw and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the Publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Georges Bataille's writings are O Editions Gallimard, Paris. Distributed by The MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bataille, Georges, 1897-1962 The cradle of humanity: prehistoric art and culture/ by Georges Bataille : edited and introduced by Stum Kendall ; translated by Michelle Kendall and Stum Kendall. P· cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 1-890951-55-2 l. Art, prehistoric and science. I. Kendall, Stuart. II. Title. N5310.B382 2004 709'.01 -dc21 Original from Digitized by UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Google Contents Editor's Introduction: The Sediment ofthe Possible 9 A Note on the Translation 33 Primitive Art 35 I The Frobenius Exhibit at the Salle Pleyel 45 II A Visit to Lascaux: A Lecture at the Sociiti d'A9riculture, Sciences, Belles-Lettres III et Arts d'Orlians 47 The Passa9efrom -

Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art

Bataille on Lascaux and the Origins of Art Richard White Creighton University Bataille’s book Lacaux has not received much scholarly attention. This essay attempts to fill in a gap in the literature by explicating Bataille’s scholarship on Lascaux to his body of writing as a whole—an exercise that, arguably, demonstrates the significance of the book and, consequently, the shortsightedness of its neglect by critics who have not traditionally grasped the relevance of the text for illuminating Bataille’s theory of art and transgression. Bataille’s major work on the Lascaux cave paintings, Prehistoric Paint- ing: Lascaux or the Birth of Art, was originally published as the first volume in a series called “The Great Centuries of Painting.”1 It is an impressive book with color photographs and supporting documents, and in his text, Bataille deals conscientiously with the existing state of prehistoric studies and scholarly accounts of Lascaux. But in spite of this—or rather because of it—Lascaux the book has received very little attention from prehistoric scholars, art historians or even Bataille enthusiasts.2 For one thing, the format of this work seems to undermine the power of transgression which is the subject as well as the driving force behind most of Bataille’s writings. The very context of a multi-volume series on great art and artists suggests an uncritical perception of art as a universal which remains the same from Lascaux to Manet.3 In Lascaux, as opposed to most of his other writings, Bataille offers his own contribution to an existing historical controversy, and he is constrained in advance by the terms of this debate. -

Of the Nineteenth-Century Maloti- Drakensberg Mountains1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by UCL Discovery The ‘Interior World’ of the Nineteenth-Century Maloti- Drakensberg Mountains1 Rachel King*1, 2, 3 and Sam Challis3 1 Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom 2 McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom 3 Rock Art Research Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Over the last four decades archaeological and historical research has the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains as a refuge for Bushmen as the nineteenth-century colonial frontier constricted their lifeways and movements. Recent research has expanded on this characterisation of mountains-as-refugia, focusing on ethnically heterogeneous raiding bands (including San) forging new cultural identities in this marginal context. Here, we propose another view of the Maloti-Drakensberg: a dynamic political theatre in which polities that engaged in illicit activities like raiding set the terms of colonial encounters. We employ the concept of landscape friction to re-cast the environmentally marginal Maloti-Drakensberg as a region that fostered the growth of heterodox cultural, subsistence, and political behaviours. We introduce historical, rock art, and ‘dirt’ archaeological evidence and synthesise earlier research to illustrate the significance of the Maloti-Drakensberg during the colonial period. We offer a revised southeast-African colonial landscape and directions for future research. Keywords Maloti-Drakensberg, Basutoland, AmaTola, BaPhuthi, creolisation, interior world 1 We thank Lara Mallen, Mark McGranaghan, Peter Mitchell, and John Wright for comments on this paper. This research was supported by grants from the South African National Research Foundation’s African Origins Platform, a Clarendon Scholarship from the University of Oxford, the Claude Leon Foundation, and the Smuts Memorial Fund at Cambridge. -

Zimbabwe Mobilizes ICAC’S Shift from Coup De Grâce to Cultural Coup

dialogue Zimbabwe Mobilizes ICAC’s Shift from Coup de Grâce to Cultural Coup Ruth Simbao, Raphael Chikukwa, Jimmy Ogonga, Berry Bickle, Marie Hélène Pereira, Dulcie Abrahams Altass, Mhoze Chikowero, and N’Goné Fall To whom does Africa belong? Whose Africa are we talking about? … R S is a Professor of Art History and Visual Culture and It’s time we control our narrative, and contemporary art is a medium the National Research Foundation/Department of Science and Tech- that can lead us to do this. nology SARChI Chair in the Geopolitics and the Arts of Africa in the National Gallery of Zimbabwe () Fine Art Department at Rhodes University, South Africa. r.simbao@ ru.ac.za Especially aer having taken Zimbabwe to Venice, we needed to bring R C is the Chief Curator at the National Gallery of the world to Zimbabwe to understand the context we are working in. Zimbabwe in Harare, and has been instrumental in establishing the Raphael Chikukwa (Zvomuya b) Zimbabwe Platform at the Venice Biennale. J O is an artist and producer based in Malindi, Kenya. he International Conference on African Cultures His work interweaves between artistic practice and curatorial strate- (ICAC) was held at the National Gallery of gies, and his curatorial projects include e Mombasa Billboard Proj- Zimbabwe in Harare from September –, ect (2002, Mombasa), and Amnesia (2006-2009, Nairobi). In 2001, . Eight delegates write their reections on he founded Nairobi Arts Trust/Centre of Contemporary Art, Nairobi (CCAEA), an organization that works as a catalyst for the visual arts the importance of this Africa-based event. -

![Repainting of Images on Rock in Australia and the Maintenance of Aboriginal Culture [1988]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7256/repainting-of-images-on-rock-in-australia-and-the-maintenance-of-aboriginal-culture-1988-1707256.webp)

Repainting of Images on Rock in Australia and the Maintenance of Aboriginal Culture [1988]

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/269164534 REPAINTING OF IMAGES ON ROCK IN AUSTRALIA AND THE MAINTENANCE OF ABORIGINAL CULTURE [1988] Article in Antiquity · December 1988 DOI: 10.1017/S0003598X00075086 CITATIONS READS 34 212 4 authors, including: Graeme K Ward Australian National University 75 PUBLICATIONS 1,081 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Cosmopolitanism, Social Justice and Global Archaeology View project Pathway Project View project All content following this page was uploaded by Graeme K Ward on 06 December 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. REPAINTING OF IMAGES ON ROCK IN AUSTRALIA AND THE MAINTENANCE OF ABORIGINAL CULTURE [1988] David MOWALJARLAI Wanang Ngari Corporation, PO Box 500, Derby WA 6723 Patricia VINNICOMBE Department of Aboriginal Sites, Western Australian Museum, Perth WA 6005 Graeme K WARD Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601 Christopher CHIPPINDALE Cambridge University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Downing Street, Cambridge CB2 3DZ Published in Antiquity 62 (237): 690-696 (December 1988) Introduction This paper has grown out of public and private discussions at the First AURA (Australian Rock Art Research Association) Congress held in Darwin (NT), Australia, in August 1988. DM is a traditional Aboriginal ‘lawman’ concerned to make his viewpoint known to a wider audience following controversy over the repainting of images in rock-shelters in his territory, A highlight of the AURA Congress was the participation of Australian Aboriginal people. They and their ancestors are the source of the painted and engraved images discussed in Australian sections of the conference and seen on field excursions. -

Southern African Rock Art : Problems of Interpretation*

SOUTHERN AFRICAN ROCK ART : PROBLEMS OF INTERPRETATION* by Kyalo Mativo This essay sets out to investigate the concepts and ideas behind the current controversy surrounding different interpretations of Southern African rock art. These interpretations fall into three categories: the aesthetic interpretation, the functionalist perception and the materialist viewpoint. Each of these 'models' is discussed briefly to delineate the assumptions underlying corresponding arguments. The implications of the whole question of interpreting southern African rock art are drawn to inculpate the interpreters in the tragic 'disappearance' of the southern San community whose artistic wealth the interpreters have inherited. For their audible silence on the genocidal crime committed against this African people incriminates them as historical accomplices in the act. The extent to which indigenous participation is excluded from the interpretation gives the debate a foreign taste, thereby removing it farther away from the reality of the African people. Needless to say, the arguments advanced in this analysis are not a detached academic description of the "main trends" genre. The thesis here is that the ' model' of interpretation one adopts l eads to definite conclusions with definite social implications. There are two perceptions under investigation here: the idealist approach and the materialist point of reference. The generalisations corresponding to the one are necessarily different from, and in certain cases actually antagonistic to the other. In this matrix of opposing viewpoints, an eclectic approach would seem to be a sure loser. Nevertheless, inasmuch as a ' model ' acknowledges contributions by others, any approach is electic in function. It is only when a given 'model' make~ a unilateral declaration of independence of perception that it ceases to be eclectic and assumes full responsibility for the consequences of its action.