The Life and Times of Jesus the Messiah Edersheim, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Among Good Women: the Social and Religious Impact of the Cathar Perfectae in the Thirteenth-Century Lauragais

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 12-2017 Life among Good Women: The Social and Religious Impact of the Cathar Perfectae in the Thirteenth-Century Lauragais Derek Robert Benson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the European History Commons, and the History of Gender Commons Recommended Citation Benson, Derek Robert, "Life among Good Women: The Social and Religious Impact of the Cathar Perfectae in the Thirteenth-Century Lauragais" (2017). Master's Theses. 2008. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/2008 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIFE AMONG GOOD WOMEN: THE SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS IMPACT OF THE CATHAR PERFECTAE IN THE THIRTEENTH-CENTURY LAURAGAIS by Derek Robert Benson A thesis submitted to the Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts History Western Michigan University December 2017 Thesis Committee: Robert Berkhofer III, Ph.D., Chair Larry Simon, Ph.D. James Palmitessa, Ph.D. LIFE AMONG GOOD WOMEN: THE SOCIAL AND RELIGIOUS IMPACT OF THE CATHAR PERFECTAE IN THE THIRTEENTH-CENTURY LAURAGAIS Derek Robert Benson, M.A. Western Michigan University, 2017 This Master’s Thesis builds on the work of previous historians, such as Anne Brenon and John Arnold. It is primarily a study of gendered aspects in the Cathar heresy. -

THE CORRUPTION of ANGELS This Page Intentionally Left Blank the CORRUPTION of ANGELS

THE CORRUPTION OF ANGELS This page intentionally left blank THE CORRUPTION OF ANGELS THE GREAT INQUISITION OF 1245–1246 Mark Gregory Pegg PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD COPYRIGHT 2001 BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PUBLISHED BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 41 WILLIAM STREET, PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY 08540 IN THE UNITED KINGDOM: PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS, 3 MARKET PLACE, WOODSTOCK, OXFORDSHIRE OX20 1SY ALL RIGHTS RESERVED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA PEGG, MARK GREGORY, 1963– THE CORRUPTION OF ANGELS : THE GREAT INQUISITION OF 1245–1246 / MARK GREGORY PEGG. P. CM. INCLUDES BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND INDEX. ISBN 0-691-00656-3 (ALK. PAPER) 1. ALBIGENSES. 2. LAURAGAIS (FRANCE)—CHURCH HISTORY. 3. INQUISITION—FRANCE—LAURAGAIS. 4. FRANCE—CHURCH HISTORY—987–1515. I. TITLE. DC83.3.P44 2001 272′.2′0944736—DC21 00-057462 THIS BOOK HAS BEEN COMPOSED IN BASKERVILLE TYPEFACE PRINTED ON ACID-FREE PAPER. ∞ WWW.PUP.PRINCETON.EDU PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA 13579108642 To My Mother This page intentionally left blank CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ix 1 Two Hundred and One Days 3 2 The Death of One Cistercian 4 3 Wedged between Catha and Cathay 15 4 Paper and Parchment 20 5 Splitting Heads and Tearing Skin 28 6 Summoned to Saint-Sernin 35 7 Questions about Questions 45 8 Four Eavesdropping Friars 52 9 The Memory of What Was Heard 57 10 Lies 63 11 Now Are You Willing to Put That in Writing? 74 12 Before the Crusaders Came 83 13 Words and Nods 92 14 Not Quite Dead 104 viii CONTENTS 15 One Full Dish of Chestnuts 114 16 Two Yellow Crosses 126 17 Life around a Leaf 131 NOTES 133 BIBLIOGRAPHY OF WORKS CITED 199 INDEX 219 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS HE STAFF, librarians, and archivists of Olin Library at Washing- ton University in St. -

Cathar Or Catholic: Treading the Line Between Popular Piety and Heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271

Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. Master’s Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Department of History William Kapelle, Advisor In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Master’s Degree by Elizabeth Jensen May 2013 Copyright by Elizabeth Jensen © 2013 ABSTRACT Cathar or Catholic: Treading the line between popular piety and heresy in Occitania, 1022-1271. A thesis presented to the Department of History Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Waltham, Massachusetts By Elizabeth Jensen The Occitanian Cathars were among the most successful heretics in medieval Europe. In order to combat this heresy the Catholic Church ordered preaching campaigns, passed ecclesiastic legislation, called for a crusade and eventually turned to the new mechanism of the Inquisition. Understanding why the Cathars were so popular in Occitania and why the defeat of this heresy required so many different mechanisms entails exploring the development of Occitanian culture and the wider world of religious reform and enthusiasm. This paper will explain the origins of popular piety and religious reform in medieval Europe before focusing in on two specific movements, the Patarenes and Henry of Lausanne, the first of which became an acceptable form of reform while the other remained a heretic. This will lead to a specific description of the situation in Occitania and the attempts to eradicate the Cathars with special attention focused on the way in which Occitanian culture fostered the growth of Catharism. In short, Catharism filled the need that existed in the people of Occitania for a reformed religious experience. -

MTG-Pl Documentation Release 0.10.1B

MTG-pl Documentation Release 0.10.1b Dominik Kozaczko & strefa-gry.pl Nov 12, 2018 Contents 1 Instrukcje 1 2 Tłumaczenie dodatków 3 2.1 Standard...............................................3 2.2 Modern................................................3 2.3 Pozostałe...............................................4 2.4 Specjalne karty............................................4 3 Warto przeczytac´ 5 4 Ostatnie zmiany 7 5 Ekipa 9 5.1 Origins................................................9 5.2 Battle for Zendikar.......................................... 25 5.3 Dragons of Tarkir........................................... 41 5.4 Uzasadnienie tłumaczen´....................................... 57 5.5 Innistrad............................................... 58 5.6 Dark Ascension........................................... 73 5.7 Avacyn Restored........................................... 83 5.8 Magic the Gathering - Basic Rulebook............................... 95 5.9 Return to Ravnica.......................................... 122 5.10 Gatecrash............................................... 136 5.11 Dragon’s Maze............................................ 150 5.12 Magic 2014 Core Set......................................... 159 5.13 Theros................................................ 171 5.14 Heroes of Theros........................................... 185 5.15 Face the Hydra!........................................... 187 5.16 Commander 2013.......................................... 188 5.17 Battle the Horde!.......................................... -

Peter Saccio

Great Figures of the New Testament Parts I & II Amy-Jill Levine, Ph.D. PUBLISHED BY: THE TEACHING COMPANY 4840 Westfields Boulevard, Suite 500 Chantilly, Virginia 20151-2299 1-800-TEACH-12 Fax—703-378-3819 www.teach12.com Copyright © The Teaching Company, 2002 Printed in the United States of America This book is in copyright. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written permission of The Teaching Company. Amy-Jill Levine, Ph.D. E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Professor of New Testament Studies Vanderbilt University Divinity School/ Vanderbilt University Graduate Department of Religion Amy-Jill Levine earned her B.A. with high honors in English and Religion at Smith College, where she graduated magna cum laude and was a member of Phi Beta Kappa. Her M.A. and Ph.D. in Religion are from Duke University, where she was a Gurney Harris Kearns Fellow and W. D. Davies Instructor in Biblical Studies. Before moving to Vanderbilt, she was Sara Lawrence Lightfoot Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religion at Swarthmore College. Professor Levine’s numerous publications address Second-Temple Judaism, Christian origins, Jewish-Christian relations, and biblical women. She is currently editing the twelve-volume Feminist Companions to the New Testament and Early Christian Literature for Continuum, completing a manuscript on Hellenistic Jewish narratives for Harvard University Press, and preparing a commentary on the Book of Esther for Walter de Gruyter (Berlin). -

Bogomils of Bulgaria and Bosnia

BOGOMILS OF BULGARIA AND BOSNIA The Early Protestants of the East. AN ATTEMPT TO RESTORE SOME LOST LEAVES OF PROTESTANT HISTORY. BY L. P. BROCKETT, M. D. Author of: "The Cross and the Crescent," "History of Religious Denominations," etc. PHILADELPHIA AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY, 1420 CHESTNUT STREET. Entered to Act of Congress, in the year 1879, by the AMERICAN BAPTIST PUBLICATION SOCIETY, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. CONTENTS _______ SECTION I. Introduction.—The Armenian and other Oriental churches. SECTION II. Dualism and the phantastic theory of our Lord's advent in the Oriental churches —The doctrines they rejected.—They held to baptism. SECTION III. Gradual decline of the dualistic doctrine —The holy and exemplary lives of the Paulicians. SECTION IV. The cruelty and bloodthirstiness of the Empress Theodora —The free state and city of Tephrice. SECTION V. The Sclavonic development of the Catharist or Paulician churches.—Bulgaria, Bosnia, and Servia its principal seats —Euchites, Massalians, and Bogomils SECTION VI. The Bulgarian Empire and its Bogomil czars. SECTION VII. A Bogomil congregation and its worship —Mostar, on the Narenta. SECTION VIII. The Bogomilian doctrines and practices —The Credentes and Perfecti —Were the Credentes baptized? SECTION IX. The orthodoxy of the Greek and Roman churches rather theological than practical —Fall of the Bulgarian Empire. SECTION X. The Emperor Alexius Comnenus and the Bogomil Elder Basil —The Alexiad of the Princess Anna Comnena. SECTION XI. The martyrdom of Basil —The Bogomil churches reinforced by the Armenian Paulicians under the Emperor John Zimisces. SECTION XII. The purity of life of the Bogomils —Their doctrines and practices —Their asceticism. -

PROMOTIONAL ORIGINAL (Un-Lim & A/B)

The Official TLG Redemption® CCG Price Guide AUGUST 2018 V1.0 Job $20.00 Stillness $2.50 PROMOTIONAL John $2.50 The Serpent $20.00 Year: N/A Cards: 96 Set: $875.00* Includes Product & Tournament cards Jonathan, son of Joiada $5.00 The Tabernacle $30.00 *Price does not include (’__ Nats) cards Joshua (District) $4.50 The Watchman $5.00 ______________________________________________________________________________________ A Child is Born $4.00 Joshua (Settlers) $7.25 Thorn in the Flesh $4.00 Abram’s Army $26.00 King David $16.50 Walking on Water $4.00 Adonijah $2.50 King Solomon $5.00 Water to Wine $2.00 Angel at Shur $4.00 Laban $5.00 Whirlwind/Everlasting Ground$30.00 Angel Food $2.00 Laban (2018) $15.00 Windows of Narrow Light $2.00 Angel of the Lord (‘16 Nats) $75.00 Lost Soul $2.00 Wings of Calamity $2.00 Angel of the Lord (‘17 Nats) $75.00 Lost Soul 2016 $15.00 Zerubbabel $4.00 Angel of the Lord (‘18 Nats) $75.00 Love $2.00 Authority of Christ $7.75 Majestic Heavens $15.00 ORIGINAL (un-lim & a/b) Mary (Chriatmas) $2.00 Year: ’95/’96 Cards: 170 Set: $65.00 Bartimaeus $2.50 Sealed Box: $40.50 Pack: $.90 Blank (both sides) $2.50 Mary's Prophetic Act $2.50 Sealed Deck: $25.00 ______________________________________________________________________________________ Meditiation $2.00 Blank (w/ Redemption back) $4.00 Aaron's Rod $0.50 Michael (‘17 Nats) $75.00 Boaz’s Sandal $5.00 Abaddon the Destroyer $0.75 Mighty Warrior $2.00 Book of the Covenant $5.00 Abandonment $0.50 New Jerusalem $9.75 Brass Serpent $5.25 Abihu $0.25 Nicanor $4.00 Burial -

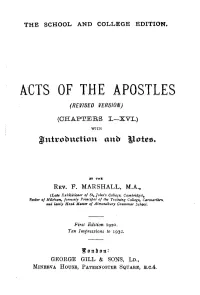

A:Cts of the Apostles (Revised Version)

THE SCHOOL AND COLLEGE EDITION. A:CTS OF THE APOSTLES (REVISED VERSION) (CHAPTERS I.-XVI.) WITH BY THK REV. F. MARSHALL, M.A., (Lau Ezhibition,r of St, John's College, Camb,idge)• Recto, of Mileham, formerly Principal of the Training College, Ca11narthffl. and la1ely Head- Master of Almondbury Grammar School, First Edition 1920. Ten Impressions to 1932. Jonb.on: GEORGE GILL & SONS, Ln., MINERVA HOUSE, PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.4. MAP TO ILLUSTRATE THE ACTS OPTBE APOSTLES . <t. ~ -li .i- C-4 l y .A. lO 15 20 PREFACE. 'i ms ~amon of the first Sixteen Chapters of the Acts of the Apostles is intended for the use of Students preparing for the Local Examina tions of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge and similar examinations. The Syndicates of the Oxford and Cambridge Universities often select these chapters as the subject for examination in a particular year. The Editor has accordingly drawn up the present Edition for the use of Candidates preparing for such Examinations. The Edition is an abridgement of the Editor's Acts of /ht Apostles, published by Messrs. Gill and Sons. The Introduction treats fully of the several subjects with which the Student should be acquainted. These are set forth in the Table of Contents. The Biographical and Geographical Notes, with the complete series of Maps, will be found to give the Student all necessary information, thns dispensing with the need for Atlas, Biblical Lictionary, and other aids. The text used in this volume is that of the Revised Version and is printed by permission of the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, but all editorial responsibility rests with the editor of the present volume. -

The Adorabyssal Oracle

THE ADORABYSSAL ORACLE The Adorabyssal Oracle is an oracle deck featuring the cutest versions of mythological, supernatural, and cryptozoological creatures from around the world! Thirty-six spooky cuties come with associated elements and themes to help bring some introspection to your day-to-day divinations and meditations. If you’re looking for something a bit more playful, The Adorabyssal Oracle deck doubles as a card game featuring those same cute and spooky creatures. It is meant for 2-4 players and games typically take 5-10 minutes. If you’re interested mainly in the card game rules, you can skip past the next couple of sections. However you choose to use your Adorabyssal Deck, it is my hope that these darkly delightful creatures will bring some fun to your day! WHAT IS AN ORACLE DECK? An Oracle deck is similar to, but different from, a Tarot deck. Where a Tarot deck has specific symbolism, number of cards, and a distinct way of interpreting card meanings, Oracle decks are a bit more free-form and their structures are dependent on their creators. The Adorabyssal Oracle, like many oracle decks, provides general themes accompanying the artwork. The basic and most prominent structure for this deck is the grouping of cards based on elemental associations. My hope is that this deck can provide a simple way to read for new readers and grow in complexity from there. My previous Tarot decks have seen very specific interpretation and symbolism. This Oracle deck opens things up a bit. It can be used for more general or free-form readings, and it makes a delightful addition to your existing decks. -

The Castle and the Virgin in Medieval

I 1+ M. Vox THE CASTLE AND THE VIRGIN IN MEDIEVAL AND EARLY RENAISSANCE DRAMA John H. Meagher III A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 1976 Approved by Doctoral Committee BOWLING GREEN UN1V. LIBRARY 13 © 1977 JOHN HENRY MEAGHER III ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 11 ABSTRACT This study examined architectural metaphor and setting in civic pageantry, religious processions, and selected re ligious plays of the middle ages and renaissance. A review of critical works revealed the use of an architectural setting and metaphor in classical Greek literature that continued in Roman and medieval literature. Related examples were the Palace of Venus, the House of Fortune, and the temple or castle of the Virgin. The study then explained the devotion to the Virgin Mother in the middle ages and renaissance. The study showed that two doctrines, the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption of Mary, were illustrated in art, literature, and drama, show ing Mary as an active interceding figure. In civic pageantry from 1377 to 1556, the study found that the architectural metaphor and setting was symbolic of a heaven or structure which housed virgins personifying virtues, symbolically protective of royal genealogy. Pro tection of the royal line was associated with Mary, because she was a link in the royal line from David and Solomon to Jesus. As architecture was symbolic in civic pageantry of a protective place for the royal line, so architecture in religious drama was symbolic of, or associated with the Virgin Mother. -

Hamlet the Heretic: the Prince's Albigensian Rhetoric

religions Article Hamlet the Heretic: The Prince’s Albigensian Rhetoric Benjamin Lockerd Department of English, Grand Valley State University, Allendale, MI 49401, USA; [email protected] Received: 19 November 2018; Accepted: 28 December 2018; Published: 29 December 2018 Abstract: Some of Hamlet’s speeches reflect a dualistic view of the world and of humanity, echoing in particular some of the heretical beliefs of the Albigensians in southern France some centuries earlier. The Albigensians thought that the evil deity created the human body as a trap for the souls created by the good god, and Hamlet repeatedly expresses disgust with the body, a “quintessence of dust” (II.ii.304–305). Because they regarded the body as a soul trap, the Albigensians believed that marriage and procreation should be avoided. “Why wouldst thou be a breeder of sinners?” Hamlet demands of Ophelia, adding that “it were better my mother had not borne me” (III.i.121–24). He sounds most like a heretic when he goes on to say “we will have no more marriage” (III.i.147). Though Hamlet continues with dualistic talk nearly to the end, there is some turning toward orthodox Christianity. Keywords: Hamlet; Albigensian heresy; Dualism; Catholicism This essay will suggest that some of Hamlet’s speeches reflect a dualistic view of the world and of humanity, echoing in particular some of the heretical beliefs of the Albigensians in southern France a couple of centuries earlier. I do not propose this interpretation as a definitive one that supersedes all the excellent scholarship of the past but as one more layer of meaning in this astonishingly complex and mysterious play, which continues to challenge us with “thoughts beyond the reaches of our souls” (I.iv.56). -

Ntral Railroad

: •-.- ,: . nor .Vrranprmfnil 356, - , utral Railroad I . Mpta/irao! "Uajruo. iJuolii.iiB, .,„. - „ . , .. nte Irnitih arirt ilir"ttfh Iff. »., . ' . .. 'r^&jJR i f|. ring uitqtinletl f«i UIIIM -.* i itoraT*w Ji.|»»y, PfaWeHr.jwaj; je;l«M •».( VUKlnla. fluww H •. - . • jt.tilav Wifl'fli.jHi'ti ne^fnl atsil We.tn. ii , i.. I'.alnmurr am. Uhit '•'•>',», . • ' ', ~,•i j, s. * n.:«. |l (Vni.«iOr,h>.l.HileMtaai»v.v'l niUH.KSTO\VX, JEfFERSON COUXTY, VIRGINIA, nil, a <'rnlt«l Ibrt'Mh IB. ,>.•'., I Itwie IP Tana on ,| l |,.,. i tin. trad the 25,. 1856. ll,,!,,! w.., ,. 11,.,-Milatd » - ~ I-AIMMIIIC NUNTIMHMTit. n. \v. m;ititi;uB, BALTIMORE LOCK HOSPITAL. Kn'inM™ TiUri'it Mfrr riign, innu.il of «n« POLJTIGAL ,,,'mV., ,,,.,.„»..„ In all POETRX. rtng-t* hin lirt-ii ii'ii.l m loob ormifonl Tha Killmor's an.l Donabon Ol»»nrf HPott- hranchr* of IKe In.nranci* Ro«ln^«n anil I. tor. Joiiruioti* jiratiuo Itct .press Upou llio'ihroe Bri.t tilts the nmnlt WM, I- •, I I, .>..!,< VI.IH1I -•-. LIFE, AND PIIIK IN8UB- lEIl OP THIS ORUCtmATED laurf, KT , rrcentl) trrsl'J » tron undom- . l i n-.'i.i-it. i> «;...nt,i . A; In nttjr «ninunl» n,put. 4. in Hi.. 11.ml,,1,1 tffft* i\\f mn«i Certain, Hfw«0jr, thil Mr. J. I! lltnotm, nf (M.nl.f, •* p»)« in honur of thrlr c»n<JiJ«»'» 1'reri- •iid oolr effectual ttnrAy In I h* wot til for »T I* P" AT1I T «« II CUT. I'rr.ljeutuf t^e,.Amer- PVfNiM-i «**>;*• ''Tmif^rg'fyi *•*"•* -*•.» , ,,„.,.