Middlebrow Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Tribute to Kishore Kumar

Articles by Prince Rama Varma Tribute to Kishore Kumar As a child, I used to listen to a lot of Hindi film songs. As a middle aged man, I still do. The difference however, is that when I was a child I had no idea which song was sung by Mukesh, which song by Rafi, by Kishore and so on unlike these days when I can listen to a Kishore song I have never heard before and roughly pinpoint the year when he may have sung it as well as the actor who may have appeared on screen. On 13th October 1987, I heard that Kishore Kumar had passed away. In the evening there was a tribute to him on TV which was when I discovered that 85% of my favourite songs were sung by him. Like thousands of casual music lovers in our country, I used to be under the delusion that Kishore sang mostly funny songs, while Rafi sang romantic numbers, Mukesh,sad songs…and Manna Dey, classical songs. During the past twenty years, I have journeyed a lot, both in music as well as in life. And many of my childhood heroes have diminished in stature over the years. But a few…..a precious few….have grown……. steadily….and continue to grow, each time I am exposed to their brilliance. M.D.Ramanathan, Martina Navratilova, Bruce Lee, Swami Vivekananda, Kunchan Nambiar, to name a few…..and Kishore Kumar. I have had the privilege of studying classical music for more than two and a half decades from some truly phenomenal Gurus and I go around giving lecture demonstrations about how important it is for a singer to know an instrument and vice versa. -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Oscar-Winning 'Slumdog Millionaire:' a Boost for India's Global Image?

ISAS Brief No. 98 – Date: 27 February 2009 469A Bukit Timah Road #07-01, Tower Block, Singapore 259770 Tel: 6516 6179 / 6516 4239 Fax: 6776 7505 / 6314 5447 Email: [email protected] Website: www.isas.nus.edu.sg Oscar-winning ‘Slumdog Millionaire’: A Boost for India’s Global Image? Bibek Debroy∗ Culture is difficult to define. This is more so in a large and heterogeneous country like India, where there is no common language and religion. There are sub-cultures within the country. Joseph Nye’s ‘soft power’ expression draws on a country’s cross-border cultural influences and is one enunciated with the American context in mind. Almost tautologically, soft power implies the existence of a relatively large country and the term is, therefore, now also being used for China and India. In the Indian case, most instances of practice of soft power are linked to language and literature (including Indians writing in English), music, dance, cuisine, fashion, entertainment and even sport, and there is no denying that this kind of cross-border influence has been increasing over time, with some trigger provided by the diaspora. The film and television industry’s influence is no less important. In the last few years, India has produced the largest number of feature films in the world, with 1,164 films produced in 2007. The United States came second with 453, Japan third with 407 and China fourth with 402. Ticket sales are higher for Bollywood than for Hollywood, though revenue figures are much higher for the latter. Indian film production is usually equated with Hindi-language Bollywood, often described as the largest film-producing centre in the world. -

A Case of Street Vendor Evictions in Bengaluru

The Role of Informality in Shaping Public Space in India: A Case of Street Vendor Evictions in Bengaluru (Mohandas, Meghna) ([email protected]) 1 Abstract: The unequal treatment of citizens based on identity, class and income is a phenomenon that can be observed in most countries of the world, including democracies. In the particular case of street vending, which is a socially and economically relevant informal activity that is prevalent in both rural and urban areas of India, the issue of evictions from public spaces by authorities is a regular phenomenon. In recent years, multiple civil society organizations have formed coalitions and developed a voice to protect street vendors from exploitation by various groups that hold positions of power (Lintelo, 2010). Their efforts have resulted in policies and acts that aim to regulate the act of street vending in India. However, the legal systems introduced by the government to resolve issues of street vendors have many loopholes. Some of these drawbacks have been utilized by people in positions of power to evict street vendors from their locations of work. An example of this is the evictions of street vendors from outside the Lakshmi Devi Park, Bengaluru, that was orchestrated by the local resident’s association, along with the police force. This article aims to raise questions on the illegal status of street vending in India, and its relevance in a neo-liberal context of growing inequality. Keywords: Street Vending, Informality, Public Space, Urban 2 “The cities everyone wants to live in should be clean and safe, possess efficient public services, be supported by a dynamic economy, provide cultural stimulation, and also do their best to heal society's divisions of race, class, and ethnicity. -

Games+Production.Pdf

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Banks, John& Cunningham, Stuart (2016) Games production in Australia: Adapting to precariousness. In Curtin, M & Sanson, K (Eds.) Precarious creativity: Global media, local labor. University of California Press, United States of America, pp. 186-199. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/87501/ c c 2016 by The Regents of the University of California This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. License: Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.ucpress.edu/ book.php?isbn=9780520290853 CURTIN & SANSON | PRECARIOUS CREATIVITY Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Precarious Creativity Precarious Creativity Global Media, Local Labor Edited by Michael Curtin and Kevin Sanson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. -

Koel Chatterjee Phd Thesis

Bollywood Shakespeares from Gulzar to Bhardwaj: Adapting, Assimilating and Culturalizing the Bard Koel Chatterjee PhD Thesis 10 October, 2017 I, Koel Chatterjee, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: Date: 10th October, 2017 Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the patience and guidance of my supervisor Dr Deana Rankin. Without her ability to keep me focused despite my never-ending projects and her continuous support during my many illnesses throughout these last five years, this thesis would still be a work in progress. I would also like to thank Dr. Ewan Fernie who inspired me to work on Shakespeare and Bollywood during my MA at Royal Holloway and Dr. Christie Carson who encouraged me to pursue a PhD after six years of being away from academia, as well as Poonam Trivedi, whose work on Filmi Shakespeares inspired my research. I thank Dr. Varsha Panjwani for mentoring me through the last three years, for the words of encouragement and support every time I doubted myself, and for the stimulating discussions that helped shape this thesis. Last but not the least, I thank my family: my grandfather Dr Somesh Chandra Bhattacharya, who made it possible for me to follow my dreams; my mother Manasi Chatterjee, who taught me to work harder when the going got tough; my sister, Payel Chatterjee, for forcing me to watch countless terrible Bollywood films; and my father, Bidyut Behari Chatterjee, whose impromptu recitations of Shakespeare to underline a thought or an emotion have led me inevitably to becoming a Shakespeare scholar. -

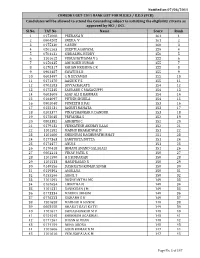

Rank List to Be Published in Web Final

Notified on 07/06/2011 COMEDK UGET2011 RANK LIST FOR M.B.B.S / B.D.S (PCB) Candidates will be allowed to attend the Counseling subject to satisfying the eligibility criteria as approved by MCI / DCI. Sl.No. TAT No Name Score Rank 1 0172008 PRERANA N 161 1 2 0804505 SNEHA V 161 2 3 0175330 S ARUN 160 3 4 0501263 DEEPTI AGARWAL 159 4 5 0704132 SIDDALING REDDY 156 5 6 1101615 PURUSHOTHAMA V S 155 6 7 0150435 ABHISHEK KUMAR 155 7 8 0170317 ROHAN KRISHNA C R 155 8 9 0902487 SWATHI S B 155 9 10 0603497 G N DEVAMSH 155 10 11 0171470 AASHIK Y S 155 11 12 0702583 DIVYACRAGATE 154 12 13 0175345 SAURABH C MASAGUPPI 154 13 14 0603609 ASAF ALI K KAMMAR 154 14 15 0164097 PIYUSH SHUKLA 154 15 16 0902048 PUNEETH K PAI 153 16 17 0155131 JAGRITI NAHATA 153 17 18 0203377 VINAYSHANKAR R DANDUR 153 18 19 0175045 PRIYANKA S 152 19 20 0803382 ABHIJITH C 152 20 21 0179132 VENKATESH AKSHAY RAAG 152 21 22 1101582 MADHU BHARADWAJ N 151 22 23 1101600 SHRINIVAS RAGHUPATHI BHAT 151 23 24 0177363 SAMYUKTA DUTTA 151 24 25 0174477 ANUJ S 151 25 26 0170418 HIMANI ANAND GALAGALI 151 26 27 0602214 VINAY PATIL S 150 27 28 1101590 H S SIDDARAJU 150 28 29 1101533 HARIPRASAD R 150 29 30 0149556 DASHRATH KUMAR SINGH 150 30 31 0159392 AMULLYA 150 31 32 0155266 AKHIL S 150 32 33 1101592 DUSHYANTHA MC 149 33 34 0167654 LIKHITHA N 149 34 35 1101531 RAVIKIRAN J M 149 35 36 0173334 MARINA AKHAM 149 36 37 0176223 RISHABH R K 149 37 38 1201628 MADHAV H HANDE 149 38 39 0603558 BHARAT RAVI KATTI 149 39 40 1101617 SHIVASHANKAR M V 148 40 41 0154545 SHUBHAM AGARWAL 148 41 42 0171261 SUSAN KURIAN 148 42 43 0174159 NEHA ARORA 148 43 44 1101606 ARUN KUMAR N M 147 44 45 1101616 VENUGOPALA K M 147 45 Page No. -

Magazine1-4Final.Qxd (Page 2)

Comical and illogical...Page 4 SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 2016 INTERNET EDITION : www.dailyexcelsior.com/magazine Why disrespect....Page 3 TALWARA goes organic Dr. Banarsi Lal Jammu and Kashmir is a mountainous state in which Jammu region is predominantly sub-tropical while Kashmir and Ladakh regions are temperate. The total geographical area of Jammu & Kashmir state is 2, 22, 236 sq. km and its population is 1, 25, 48,926 as per 2011 Census. Agriculture is the mainstay of Jammu and Kashmir state. This sector provides employment to about 70 per cent of the state population. Agriculture contributes about 65 per cent of the state revenue which signi- fies the overdependence of the state on agriculture. The average size of land holding of the state is only 0.67 hectare against 1.33 hectares' land holding size on national basis. Organic farming is picking up pace in the state and there is need of awareness and trainings of farmers for organic farming. J&K has huge potential for organic farming as the large area in the state is already under semi- organic cultivation in hilly districts of the state due to the lack of availability of chemical fertilizers in these areas and the farmers of these areas avoid to apply the chemical fertilizers. Basmati rice of R. S. Pura, rajmash of Bhaderwah, pota- to of Gurez and Machil and red rice of Tangdar, Kupwara, ginger and turmer- ic of Pouni, Reasi are major exportable organic products in the state and have the potential to fetch more returns in the market. Organic farming means holis- tic production systems which refer earth friendly methods for cultivation and food processing. -

Global Digital Cultures: Perspectives from South Asia

Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Revised Pages Revised Pages Global Digital Cultures Perspectives from South Asia ASWIN PUNATHAMBEKAR AND SRIRAM MOHAN, EDITORS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS • ANN ARBOR Revised Pages Copyright © 2019 by Aswin Punathambekar and Sriram Mohan All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by the University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid- free paper First published June 2019 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication data has been applied for. ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 13140- 2 (Hardcover : alk paper) ISBN: 978- 0- 472- 12531- 9 (ebook) Revised Pages Acknowledgments The idea for this book emerged from conversations that took place among some of the authors at a conference on “Digital South Asia” at the Univer- sity of Michigan’s Center for South Asian Studies. At the conference, there was a collective recognition of the unfolding impact of digitalization on various aspects of social, cultural, and political life in South Asia. We had a keen sense of how much things had changed in the South Asian mediascape since the introduction of cable and satellite television in the late 1980s and early 1990s. We were also aware of the growing interest in media studies within South Asian studies, and hoped that the conference would resonate with scholars from various disciplines across the humanities and social sci- ences. -

Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas the Indian New Wave

This article was downloaded by: 10.3.98.104 On: 28 Sep 2021 Access details: subscription number Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: 5 Howick Place, London SW1P 1WG, UK Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas K. Moti Gokulsing, Wimal Dissanayake, Rohit K. Dasgupta The Indian New Wave Publication details https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 Ira Bhaskar Published online on: 09 Apr 2013 How to cite :- Ira Bhaskar. 09 Apr 2013, The Indian New Wave from: Routledge Handbook of Indian Cinemas Routledge Accessed on: 28 Sep 2021 https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203556054.ch3 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR DOCUMENT Full terms and conditions of use: https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/legal-notices/terms This Document PDF may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproductions, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The publisher shall not be liable for an loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. 3 THE INDIAN NEW WAVE Ira Bhaskar At a rare screening of Mani Kaul’s Ashad ka ek Din (1971), as the limpid, luminescent images of K.K. Mahajan’s camera unfolded and flowed past on the screen, and the grave tones of Mallika’s monologue communicated not only her deep pain and the emptiness of her life, but a weighing down of the self,1 a sense of the excitement that in the 1970s had been associated with a new cinematic practice communicated itself very strongly to some in the auditorium. -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways.