A Case of Street Vendor Evictions in Bengaluru

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribute to Kishore Kumar

Articles by Prince Rama Varma Tribute to Kishore Kumar As a child, I used to listen to a lot of Hindi film songs. As a middle aged man, I still do. The difference however, is that when I was a child I had no idea which song was sung by Mukesh, which song by Rafi, by Kishore and so on unlike these days when I can listen to a Kishore song I have never heard before and roughly pinpoint the year when he may have sung it as well as the actor who may have appeared on screen. On 13th October 1987, I heard that Kishore Kumar had passed away. In the evening there was a tribute to him on TV which was when I discovered that 85% of my favourite songs were sung by him. Like thousands of casual music lovers in our country, I used to be under the delusion that Kishore sang mostly funny songs, while Rafi sang romantic numbers, Mukesh,sad songs…and Manna Dey, classical songs. During the past twenty years, I have journeyed a lot, both in music as well as in life. And many of my childhood heroes have diminished in stature over the years. But a few…..a precious few….have grown……. steadily….and continue to grow, each time I am exposed to their brilliance. M.D.Ramanathan, Martina Navratilova, Bruce Lee, Swami Vivekananda, Kunchan Nambiar, to name a few…..and Kishore Kumar. I have had the privilege of studying classical music for more than two and a half decades from some truly phenomenal Gurus and I go around giving lecture demonstrations about how important it is for a singer to know an instrument and vice versa. -

Looking at Popular Muslim Films Through the Lens of Genre

Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, Vol. IX, No. 1, 2017 0975-2935 DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v9n1.17 Full Text: http://rupkatha.com/V9/n1/v9n117.pdf Is Islamicate a Genre? Looking at Popular Muslim Films through the Lens of Genre Asmita Das Department of Film Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. ORCID: 0000-0002-7307-5818. Email: [email protected] Received February 25, 2017; Revised April 9, 2017; Accepted April 10, 2017; Published May 7, 2017. Abstract This essay engages with genre as a theory and how it can be used as a framework to determine whether Islamicate or the Muslim films can be called a genre by themselves, simply by their engagement with and representation of the Muslim culture or practice. This has been done drawing upon the influence of Hollywood in genre theory and arguments surrounding the feasibility / possibility of categorizing Hindi cinema in similar terms. The essay engages with films representing Muslim culture, and how they feed into the audience’s desires to be offered a window into another world (whether it is the past or the inner world behind the purdah). It will conclude by trying to ascertain whether the Islamicate films fall outside the categories of melodrama (which is the most prominent and an umbrella genre that is represented in Indian cinema) and forms a genre by itself or does the Islamicate form a sub-category within melodrama. Keywords: genre, Muslim socials, socials, Islamicate films, Hindi cinema, melodrama. 1. Introduction The close association between genre and popular culture (in this case cinema) ensured generic categories (structured by mass demands) to develop within cinema for its influence as a popular art. -

Nation, Fantasy, and Mimicry: Elements of Political Resistance in Postcolonial Indian Cinema

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA Aparajita Sengupta University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sengupta, Aparajita, "NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA" (2011). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 129. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Aparajita Sengupta The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2011 NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Aparajita Sengupta Lexington, Kentucky Director: Dr. Michel Trask, Professor of English Lexington, Kentucky 2011 Copyright© Aparajita Sengupta 2011 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION NATION, FANTASY, AND MIMICRY: ELEMENTS OF POLITICAL RESISTANCE IN POSTCOLONIAL INDIAN CINEMA In spite of the substantial amount of critical work that has been produced on Indian cinema in the last decade, misconceptions about Indian cinema still abound. Indian cinema is a subject about which conceptions are still muddy, even within prominent academic circles. The majority of the recent critical work on the subject endeavors to correct misconceptions, analyze cinematic norms and lay down the theoretical foundations for Indian cinema. -

Find Kindle // the Dialogue of Pyaasa: Guru Dutt`S Immortal Classic

XESF2STZLVRV ^ Book » The Dialogue of Pyaasa: Guru Dutt`s Immortal Classic Th e Dialogue of Pyaasa: Guru Dutt`s Immortal Classic Filesize: 3.54 MB Reviews A fresh e-book with a new viewpoint. Better then never, though i am quite late in start reading this one. I am happy to explain how here is the very best ebook i actually have study during my individual lifestyle and may be he greatest pdf for actually. (Diana Flatley) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GR3ZYMZ7DP9G ^ PDF # The Dialogue of Pyaasa: Guru Dutt`s Immortal Classic THE DIALOGUE OF PYAASA: GURU DUTT`S IMMORTAL CLASSIC Om Books International, Noida, Uttar Pradesh, India, 2011. So cover. Condition: New. Great films come from great writing and the aim of The Dialogue of Pyaasa, Guru Dutt's Immortal Classic is to preserve in book form the film's complete dialogue by Abrar Alvi and songs/poems by Sahir Ludhianvi. These are presented in Hindi, Urdu and Romanised scripts. Generously illustrated, the dialogue is also accompanied by an English translation, introduction and extensive commentary by Nasreen Munni Kabir. First-rate screenwriter, Abrar Alvi has created superb scenes and subtle lines. Skilled in giving personality to every Pyaasa character, Alvi's flair for lived-in expression turns Guru Dutt as Vijay or Johnny Walker as Abdul Sattar into real people. Pyaasa's other excellent writing comes from Sahir Ludhianvi's sublime songs and poetry. This master Urdu poet has been widely acknowledged for elevating the film songs to a poetic form and this is in full evidence in the film. Sahir's Marxist ideology, brilliant imagination and deep understanding of human emotions are the soul of Pyaasa. -

Deutsch-Indischer Filmclub Im Restaurant RADHA

Deutsch-Indischer Filmclub im Restaurant RADHA Jeden Mittwoch um 20:00 Uhr (Achtung: neue Anfangszeit!) werden anspruchsvolle Filme und Fernsehsendungen zu einem indischen Thema in kulinarisch-relaxter Atmosphäre präsentiert. Die Filme stammen aus den Genres: - Klassiker des indischen Films und des deutschen Films zu indischen Themen - Dokumentationen über indische Filme und die indische Filmindustrie - Deutsche Filme und Fernsehsendungen zu indischen Themen - Gute neuere Filmproduktionen aus Indien EINTRITT FREI – Indisches Filmclub-Spezial-Büffet nur 4,95 Euro Das Restaurant RADHA befindet sich in der Hardenbergstraße 9a, 10623 Berlin -Charlottenburg, zwischen Steinplatz und Ernst-Reuter-Platz, gegenüber TU-Mensa, Bus 245, Tel: 030 – 31 51 83 82 Gute Ideen und Mitarbeit beim Filmclub sind herzlich willkommen! Kontakt: [email protected] 4. Juli: MAQBOOL Regie: Vishal Bharadwaj, Indien, 2003, 132 Min., Literaturadaption/Spielfilm, Farbe, Urdu und Hindi mit englischen Untertiteln (UT) Cast: Pankaj Kapoor, Irfan Khan, Tabu, Om Puri, Naseeruddin Shah, Piyush Mishra, Ajay Gehi Macbeth meets the Godfather in present-day Bombay. The Scottish tragedy set in the contemporary underworld of India's commercial capital; two corrupt, fortune telling policemen (Om Puri and Naseeruddin Shah respectively) take the roles of the weird sisters. Jahangir Khan/Abbaji (Pankaj Kapoor) is the aging leader of a criminal gang. Nimmi (Tabu) is his mistress. Members of the gang include Maqbool (Irfan Khan), Kaka (Piyush Mishra) and his son Guddu (Ajay Gehi). Things turn ugly when his mistress, Nimmi, starts to have an affair with one of his men, Maqbool, who has aspirations of succeeding Abbaji one day. Nimmi and Maqbool plot and carry out his death; the sea plays the role of Birnham wood. -

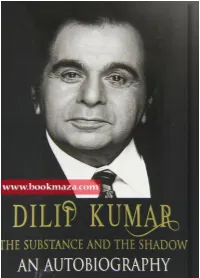

Dilip-Kumar-The-Substance-And-The

No book on Hindi cinema has ever been as keenly anticipated as this one …. With many a delightful nugget, The Substance and the Shadow presents a wide-ranging narrative across of plenty of ground … is a gold mine of information. – Saibal Chatterjee, Tehelka The voice that comes through in this intriguingly titled autobiography is measured, evidently calibrated and impossibly calm… – Madhu Jain, India Today Candid and politically correct in equal measure … – Mint, New Delhi An outstanding book on Dilip and his films … – Free Press Journal, Mumbai Hay House Publishers (India) Pvt. Ltd. Muskaan Complex, Plot No.3, B-2 Vasant Kunj, New Delhi-110 070, India Hay House Inc., PO Box 5100, Carlsbad, CA 92018-5100, USA Hay House UK, Ltd., Astley House, 33 Notting Hill Gate, London W11 3JQ, UK Hay House Australia Pty Ltd., 18/36 Ralph St., Alexandria NSW 2015, Australia Hay House SA (Pty) Ltd., PO Box 990, Witkoppen 2068, South Africa Hay House Publishing, Ltd., 17/F, One Hysan Ave., Causeway Bay, Hong Kong Raincoast, 9050 Shaughnessy St., Vancouver, BC V6P 6E5, Canada Email: [email protected] www.hayhouse.co.in Copyright © Dilip Kumar 2014 First reprint 2014 Second reprint 2014 The moral right of the author has been asserted. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All photographs used are from the author’s personal collection. All rights reserved. -

What Is It Called Good Friday? Joy Ruskin: Agency.On This His Own Sacrifice

WEEKLY www.swapnilsansar.org Simultaneously Published In Hindi Daily & Weekly VOL.23, ISSUE 14, LUCKNOW, 28 MARCH, 2018,PAGE 08,PRICE :1/- What is it called Good Friday? Joy Ruskin: Agency.On this His own sacrifice. But the question is, that if with the Jewish observance of guilt in Jesus; Pilate resolved to day Jesus Christ died on the He was made fun of, insulted Jesus Christ was crucified on this Passover.The etymology of the have Jesus whipped and released term "good" in the context of (Luke 23:3–16). Under the Good Friday is contested. Some guidance of the chief priests, the 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 30th March 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 123456789012345678901234567890121234567890123456789012 sources claim it is from the senses crowd asked for Barabbas, who pious, holy of the word "good", had been imprisoned for while others contend that it is a committing murder during an corruption of "God Friday".The insurrection. Pilate asked what Oxford English Dictionary they would have him do with supports the first etymology, Jesus, and they demanded, giving "of a day or season "Crucify him" (Mark 15:6–14). observed as holy by the church" Pilate's wife had seen Jesus in a as an archaic sense of good, and dream earlier that day, and she providing examples of good tide forewarned Pilate to "have meaning "Christmas" or "Shrove nothing to do with this righteous Tues day", and Good Wednesday man" (Matthew 27:19). Pilate had meaning the Wednesday in Jesus flogged and then brought HolyWeek.Conflicting him out to the crowd to release testimony against Jesus was him. -

The Laxmi Chhaya DVD

The Laxmi Chhaya DVD Introduction As with many other of the actors and actors in classic Indian films, not much (meaning practically nothing) of Laxmi Chhaya's personal life and her career in films is known. We know that she passed away way too early, dying of cancer about 6 years ago. Beyond that, nothing. If anyone can fill in details - family members, friends, friends of friends - perhaps you'd be so kind as to comment in memsaab's blog (link at bottom), maybe in her "My 10 Favorite Laxmi Chhaya Songs" post. There are many people around the world who love her, her dancing, and her acting in the movies available, and you'd be sure to receive a warm reception. Apparently she began her film career in 1963. I say 'apparently' because the information available is so sketchy that there's just no way to be sure it's accurate. I think her first film was 1963's Bluff Master starring Shammi Kapoor and Saira Banu (memsaab gets the credit for spotting her before the qawaali begins). I think this may have been her first film because she isn't listed in the film's credits, where for the other 2 films IMDB says she appeared in that year, she is listed in the credits. Here she is, standing beside Saira Banu: Hers was a speaking role with several lines of dialog, which makes her not appearing in the film's credits all the more peculiar. In the other 2 films she was in that year she (probably) performed her first dances. -

EROS INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION of INDIAN CINEMA on DVD Last Update: 2008-05-21 Collection 26

EROS INTERNATIONAL COLLECTION OF INDIAN CINEMA ON DVD Last Update: 2008-05-21 Collection 26 DVDs grouped by year of original theatrical release Request Titles by Study Copy No. YEAR OF THEATRICAL COLOR / RUNNING STUDY COPY NO. CODE FILM TITLE RELEASE B&W TIME GENRE DIRECTOR(S) CAST 1 DVD5768 M DVD-E-079 MOTHER INDIA 1957 color 2:43:00 Drama Mehoob Khan Nargis, Sunil Dutt, Raj Kumar 2 DVD5797 M DVD-E-751 KAAGAZ KE PHOOL 1959 color 2:23:00 Romance Guru Dutt Guru Dutt, Waheeda Rehman, Johnny Walker 3 DVD5765 M DVD-E-1060 MUGHAL-E-AZAM 1960, 2004 color 2:57:00 Epic K. Asif Zulfi Syed, Yash Pandit, Priya, re-release Samiksha 3.1 DVD5766 M DVD-E-1060 MUGHAL-E-AZAM bonus material: premier color in Mumbai; interviews; "A classic redesigned;" deleted scene & song 4 DVD5815 M DVD-E-392 CHAUDHVIN KA CHAND 1960 b&w 2:35:00 Romance M. Sadiq Guru Dutt, Waheeda Rehman, Rehman 5 DVD5825 M DVD-E-187 SAHIB BIBI AUR GHULAM 1962 b&w 2:42:00 Drama Abrar Alvi Guru Dutt, Meena Kuman, Waheeda Rehman 6 DVD5772 M DVD-E-066 SEETA AUR GEETA 1972 color 2:39:00 Drama Ramesh Sippy Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Hema Malini 7 DVD5784 M DVD-E-026 DEEWAAR 1975 color 2:40:00 Drama Yash Chopra Amitabh Bachchan, Shashi Kapoor, Parveen Babi, Neetu Singh 8 DVD5788 M DVD-E-016 SHOLAY 1975 color 3:24:00 Action Ramesh Sippy Amitabh Bachchan, Dharmendra, Sanjeev Kumar, Hema Malini 9 DVD5807 M DVD-E-256 HERA PHERI 1976 color 2:37:00 Comedy Prakash Mehra Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna, Saira Banu, Sulakshana Pandit 10 DVD5802 M DVD-E-140 KHOON PASINA 1977 color 2:31:00 Drama Rakesh Kumar Amitabh Bachchan, Vinod Khanna, Rekha 11 DVD5816 M DVD-E-845 DON 1978 color 2:40:00 Action Chandra Barot Amitabh Bachchan, Zeenat Aman, Pran 12 DVD5811 M DVD-E-024 MR. -

Middlebrow Cinema

3 MUMBAI MIDDLEBROW Ways of thinking about the middle ground in Hindi cinema Rachel Dwyer The word ‘middlebrow’, associated with Victorian phrenology and cultural snobbery, is usually a derogatory term and may not seem useful as a way of understanding Hindi cinema, now usually known as Bollywood (Rajadhyaksha 2003; Vasudevan 2010). However, the social and economic changes of the last twenty-five years, which are producing India’s growing new middle classes, a social group whose culture is closely linked to the cultural phenomenon of Bollywood (Dwyer 2000; 2014a), suggest that the term may usefully be deployed to look at the often ignored middle ground of Hindi cinema, which lies somewhere between the highbrow art cinema and lowbrow masala (‘spicy’, entertainment) films (Dwyer 2011a). I suggest that the term can be used for a certain type of contemporary Hindi cinema which can be traced back several decades, in parallel with the changes that have affected India’s middle classes. Defining the middlebrow In academic discourse, commentators have turned to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of ‘culture moyenne’ (outlined, for example, in his study of photography), to describe the middlebrow as a cultural category that is imitative of legitimate, high cul- ture, and makes art accessible in a popular form (Bourdieu 1996; 1999, 323). Beth Driscoll’s study of middlebrow literature over the twenty-first century offers eight features of the category: middle-class, reverential, commercial, feminized, medi- ated, recreational, emotional and earnest (2014, 3). Sally Faulkner, on the other hand, defines middlebrow cinema as combining high production values, subject matter that is serious but not challenging and cultural references that are presented in an accessible form (2013, 8). -

Artist Index

Artist Index A Asha Parekh (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Bharati (1960s) A.K. Hangal (1970s, 1980s) Asha Potdar (1970s) Bharti (1970s) Aamir Khan (1970s, 1980s) Asha Sachdev (1970s) Bhola (1970s) Aarti (1970s) Ashish Vidyarthi (1990s) Bhudo Advani (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Abhi Bhattacharya (1950s, 1960s, Ashok Kumar (1930s, 1940s, 1950s, Bhupinder Singh (1960s) 1970s) 1960s, 1970s) Bhushan Tiwari (1970s) Achala Sachdev (1950s, 1960s, Ashoo (1970s, 1980s) Bibbo (1940s) 1970s) Asit Sen (1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Bihari (1970s) Aditya Pancholi (1980s) Aspi Irani- director (1950s) Bikram Kapoor (1960s) Agha (1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s) Asrani (1970s) Bina Rai (1950s, 1960s) Ahmed- dancer (1950s) Avtar Gill (1990s) Bindu (1960s, 1970s) Ajay Devgan (1990s) Azad (1960s) Bipin Gupta (1940s, 1960s, 1970s) Ajit (1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s) Azim (1950s, 1960s) Bir Sakhuja (1950s, 1960s) Alan Figueiredo- musician, dancer Azra (1960s, 1970s) Birbal (1970s) (1960s) Bismillah (1930s) Alankar (Master) (1970s) B Bittoo (Master) (1970s) Alka (1970s) B.M. Vyas (1960s) Biswajeet (1960s) Amar (1940s, 1960s) B. Nandrekar (1930s) Bob Christo (1980s, 1990s) Amarnath (1950s, 1960s) Babita (1960s, 1970s) Brahm Bhardwaj (1960s, 1970s) Ameerbai Karnataki (1940s, 1960s) Baburao Pendharkar (1930s, 1940s) Ameeta (1950s, 1960s) Baby Farida (see Farida) C Amitabh Bachchan (1970s, 1980s, Baby Leela (see Leela) C.S. Dubey (1970s, 1980s) 1990s) Baby Madhuri (see Madhuri) Chaman Puri (1970s) Amjad Khan (1950s, 1980s) Baby Naaz (see Kumari Naaz) Chandramohan (1930s, 1940s) Amol Palekar (1970s) -

Hindi Cinema Artists 1950S

Hindi Cinema Artists 1950s http://memsaabstory.wordpress.com Abhi Bhattacharya (1957) Achala Sachdev (1950) Agha (1955) Ahmed (1957) Ajit (1954) Amarnath (1950) Ameeta (1959) Amjad Khan (1957) Anita Guha (1959) Anwar Hussain (1958) Asha Parekh (1959) Ashok Kumar (1952) Asit Sen (1959) Aspi Irani (1950) Azim (1952) Badri Prasad (1959) Balam (1950) Balraj Sahni (1958) All content on this page is for informational purposes only, and has been compiled from movies and other sources in my possession. If any copyright has been infringed, please contact me: memsaabstory [at] gmail [dot] com or leave a comment on my blog at http://memsaabstory.wordpress.com. Hindi Cinema Artists 1950s ~ page 2 http://memsaabstory.wordpress.com Bela Bose (1959) Bhagwan (1956) Bhagwan I (1959) Bhagwan Sinha (1954) Bharat Bhushan (1959) Bhudo Advani (1958) Bina Rai (1955) Bir Sakhuja (1958) Chandrashekhar (1955) Chetan Anand (1957) Chitra (1955) Cuckoo (1950) Daisy Irani (1958) Daljit (1955) Dalpat (1953) David Abraham (1959) Dev Anand (1955) Dhumal (1957) All content on this page is for informational purposes only, and has been compiled from movies and other sources in my possession. If any copyright has been infringed, please contact me: memsaabstory [at] gmail [dot] com or leave a comment on my blog at http://memsaabstory.wordpress.com. Hindi Cinema Artists 1950s ~ page 3 http://memsaabstory.wordpress.com Dilip Kumar (1951) Dog Moti I (1958) Dulari (1952) D.K. Sapru (1955) Durga Khote (1952) Edwina (1959) Fearless Nadia (1953) Feroz Khan (1959) Geeta Bali (1953) Gemini Ganeshan (1953) Goldstein (1951) Gope (1951) Gulab (1957) Guru Dutt (1953) Habib (1951) Helen (1955) Hiralal (1951) Honey Irani (1959) All content on this page is for informational purposes only, and has been compiled from movies and other sources in my possession.