Of Education and Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1Gary Middle College 21St Century Charter School at Gary GEO Next Generation High School-Indianapolis

1Gary Middle College 21st Century Charter School at Gary GEO Next Generation High School-Indianapolis COVID-19 Fall 2021 Learning/Reopening Plan Integrated ESSER III Plan DRAFT – for public comment Email comments to: [email protected] Date of Last Update: May 27, 2021 Summary All Indiana GEO Academies have implemented a robust plan for faculty, students and families to return to in person school for the 2021-2022 school year. You can't have a full recovery without full-strength schools. Increased vaccination opportunities combined with unfortunate learning loss, as documented by 2020-2021 assessment results, prove the need and the ability for the return to in-person education. However, GEO Academies also acknowledge that some families found virtual learning to be the best option for their students, and therefore we will also offer a virtual option - with certain provisions - for those families that found virtual learning to be a success. This plan was designed using all information currently available from the Indiana State Department of Health, the Indiana Department of Education, and the Center for Disease Control; however, it is subject to change at any time. STAKEHOLDER INPUT: ● In an effort to capture the input and needs of our families, a survey was administered that provided the district with an understanding of the preferred learning environment for the 2021-2022 school year. This survey is in addition to the outreach that was conducted from each school which included; calls, emails, Facebook Live sessions, and Parent Universities. The results from the survey revealed that the majority of families are ready to return to in- person instruction with a very small percentage wanting to remain fully virtual. -

2021 Chesterfield County Leadership for the 21St Century Scholarship Winners

BLACK HISTORY MONTH 2021 The Black Family REPRESENTATION, IDENTITY, AND DIVERSITY 2021 CHESTERFIELD COUNTY LEADERSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY SCHOLARSHIP WINNERS TERRY LEE JOHNSON, JR. is the 2020-2021 JAMAR JOHNSON is the 2020-2021 Bermuda Matoaca District scholarship recipient, attends District scholarship recipient and attends Matoaca High School and has a current 4.8 GPA. Thomas Dale High School with a 4.0 GPA. Terry Lee’s plans are to attend a Virginia college Jamar’s plans are to attend a Virginia college or or university with the intent of majoring in university with the intent of majoring in computer science. Terry has been active in track mechanical engineering. Jamar has and field events, played on the Chesterfield participated in the following activities: African Basketball League and participated in the American Culture Club, DECA and been an avid Chesterfield S.T.E.A.M Expo. athlete in football, wrestling and lacrosse. AMENAH HOLT is the 2020-2021 Midlothian MARY HALL is the 2020-2021 Clover Hill District scholarship recipient, attends District scholarship recipient and attends Midlothian High School and has a current 4.4 Monacan High School with a current 4.7 GPA. GPA. Amenah’s plans are to attend a Virginia Mary’s plans are to attend a Virginia college or college or university with the intent of university with the intent of majoring in majoring in neuroscience. Amenah has political science. Mary has been engaged in a participated in the Midlothian High School host of activities that includes Monacan Color Guard (part of the Marching Band), Theater, Monacan Choir, Monacan Tribe, Future Business Leaders of America (FBLA) Club, Midlothian Trojan Ecology Club, and served as a Freshman mentor to students at Nations, Jack and Jill of America, Inc. -

The New Insurgents: a Select Review of Recent Literature on Terrorism and Insurgency

The New Insurgents: A Select Review of Recent Literature on Terrorism and Insurgency George Michael US Air Force Counterproliferation Center Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama THE NEW INSURGENTS: A Select Review of Recent Literature on Terrorism and Insurgency by George Michael USAF Counterproliferation Center 325 Chennault Circle Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama 36112-6427 March 2014 Disclaimer The opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Air University, Air Force, or Department of Defense. ii Contents Chapter Page Disclaimer .............................................................................................. ii About the Author..................................................................................... v Introduction ........................................................................................... vii 1 Domestic Extremism and Terrorism in the United States ....................... 1 J.M. Berger, Jihad Joe: Americans Who Go to War in the Name of Islam ................................................................................................ 3 Catherine Herridge, The Next Wave: On the Hunt for Al Qaeda’s American Recruits ........................................................................... 8 Martin Durham, White Rage: The Extreme Right and American Politics ........................................................................................... 11 2 Jihadist Insurgent Strategy .................................................................... -

21St Century Cultures of War: Advantage Them

FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The Philadelphia Papers 21st Century Cultures of War: Advantage Them By Anna Simons Naval Postgraduate School April 2013 THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS st 21 Century Cultures of War: Advantage Them By Anna Simons, Naval Postgraduate School April 2013 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE www.fpri.org Published in April 2013 Note: This paper was initially submitted to the Office of Net Assessment (Office of the Secretary of Defense) in October 2012 and subsequently cleared for public release. It does not reflect the views of ONA, OSD, the U.S. Navy, or any other branch of U.S. government. Foreign Policy Research Institute 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 About the Author Anna Simons is a Professor of Defense Analysis at the Naval Postgraduate School. Prior to teaching at NPS she was both an assistant and then an associate professor of anthropology at UCLA, as well as chair of the Masters in African Area Studies Program. She holds a PhD in social anthropology from Harvard University and an A.B. from Harvard College. She is the author of Networks of Dissolution: Somalia Undone and The Company They Keep: Life Inside the U.S. Army Special Forces. Most recently she is the co-author of The Sovereignty Solution: A Commonsense Approach to Global Security. Simons' focus has been on conflict, intervention, and the military from an anthropological perspective. Her work examines ties that bind members of groups together as well as divides which drive groups apart. Articles have appeared in The American Interest, The National Interest, Small Wars & Insurgencies, Annual Review of Anthropology, Parameters, and elsewhere. -

Historical Developments in Public Health and the 21St Century

CHAPTER 2 Historical Developments in Public Health and the 21st Century James A. Johnson, James Allen Johnson III, and Cynthia B. Morrow LEARNING OBJECTIVES t To better understand the historical context of public health t To gain perspective on the role of public health in society t To grasp the key milestones in the evolution of public health practice and policy t To understand recent reform and its implications for the future of public health Chapter Overview 1VCMJDIFBMUIBENJOJTUSBUJPOBOEQSBDUJDFDPNQSJTFTPSHBOJ[FEFêPSUTUPJNQSPWFUIFIFBMUI PGQPQVMBUJPOT1VCMJDIFBMUIQSFWFOUJPOTUSBUFHJFTUBSHFUQPQVMBUJPOTSBUIFSUIBOJOEJWJEVBMT ɨSPVHIPVUIJTUPSZ QVCMJDIFBMUIFêPSUTIBWFGPDVTFEPOUIFDPOUSPMPGDPNNVOJDBCMFEJTFBTFT SFEVDJOHFOWJSPONFOUBMIB[BSET BOEQSPWJEJOHTBGFESJOLJOHXBUFS#FDBVTFTPDJBM FOWJSPO - NFOUBM BOECJPMPHJDGBDUPSTJOUFSBDUUPEFUFSNJOFIFBMUI QVCMJDIFBMUIQSBDUJDFNVTUVUJMJ[FB CSPBETFUPGTLJMMTBOEJOUFSWFOUJPOT%VSJOHUIFUIDFOUVSZ UIFIJTUPSJDFNQIBTJTPGQVCMJD IFBMUIPOQSPUFDUJOHQPQVMBUJPOTGSPNJOGFDUJPVTEJTFBTFBOEFOWJSPONFOUBMUISFBUTFYQBOEFEUP JODMVEFUIFQSFWFOUJPOBOESFEVDUJPOPGDISPOJDEJTFBTFUISPVHICFIBWJPSBMBOEMJGFTUZMFJOUFS - WFOUJPOT"TXFNPWFGPSXBSEJOUIFTUDFOUVSZOFXDIBMMFOHFTXJMMFNFSHFBOEOFXTUSBUFHJFT BOEJOJUJBUJWFTXJMMOFFEUPCFEFWFMPQFEɨFSPMFPGQVCMJDIFBMUIXJMMVOEPVCUFEMZCFDFOUSBM UPUIFXFMMCFJOHPGUIFOBUJPOBOEUIFXPSME 11 9781449657413_CH02_PASS02.indd 11 23/04/13 10:03 AM 12 Chapter 2 Historical Developments in Public Health and the 21st Century Early History of Public Health -JUUMF JT LOPXO BCPVU UIF IFBMUI PG UIF IVOUJOH BOE HBUIFSJOH QFPQMF PG QSFIJTUPSJD -

21St Century Town Hall Meetings in the 1990S and 2000S: Deliberative Demonstrations and the Commodification of Oliticalp Authenticity in an Era of Austerity

Journal of Public Deliberation Volume 15 Issue 2 Town Meeting Politics in the United States: The Idea and Practice of an American Article 2 Myth 2019 21st Century Town Hall Meetings in the 1990s and 2000s: Deliberative Demonstrations and the Commodification of oliticalP Authenticity in an Era of Austerity Caroline W. Lee Lafayette College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd Recommended Citation Lee, Caroline W. (2019) "21st Century Town Hall Meetings in the 1990s and 2000s: Deliberative Demonstrations and the Commodification of oliticalP Authenticity in an Era of Austerity," Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 15 : Iss. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol15/iss2/art2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Public Deliberation. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Public Deliberation by an authorized editor of Public Deliberation. 21st Century Town Hall Meetings in the 1990s and 2000s: Deliberative Demonstrations and the Commodification of oliticalP Authenticity in an Era of Austerity Abstract The public participation field grew dramatically in the United States during the 1990s and 2000s, in part due to the flagship dialogue and deliberation organization AmericaSpeaks and its trademarked 21st Century Town Hall Meeting method for large group decision-making. Drawing on participant observation of three such meetings and a multi-method ethnography of the larger field, I place these meetings in context as experimental deliberative demonstrations during a time of ferment regarding declining citizen capacity in the United States. AmericaSpeaks’ town meetings were branded as politically authentic alternatives to ordinary politics, but as participatory methods and empowerment discourses became popular with a wide variety of public and private actors, the organization failed to find a sustainable business model. -

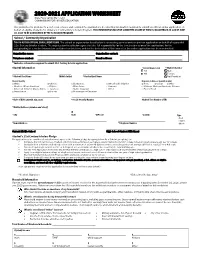

2020-2021 APPLICATION WORKSHEET State Form 56495 (R2 / 7-20) COMMISSION for HIGHER EDUCATION

2020-2021 APPLICATION WORKSHEET State Form 56495 (R2 / 7-20) COMMISSION FOR HIGHER EDUCATION This worksheet is provided to assist local schools and community organizations in collecting information required to submit an official online application on behalf of eligible students for Indiana’s 21st Century Scholars Program. THIS INFORMATION MUST BE SUBMITTED ONLINE AT WWW.SCHOLARTRACK.IN.GOV BY JUNE 30, 2021 TO BE CONSIDERED BY THE SCHOLARS PROGRAM. School / Community Organization THIS IS NOT AN OFFICIAL ENROLLMENT FORM. The school or organization listed below is requesting permission to submit an application on behalf of a potential 21st Century Scholar student. The organization listed below agrees to take full responsibility for the timely submission of the application, for the safeguarding of sensitive information contained on this form, and for the destruction of this form after the online application has been submitted. Organization name: Organization contact: Telephone number: E-mail address: * Indicates information required to submit 21st Century Scholar application. Student Information *Current Grade Level *Student Gender □ 7th □ Male □ 8th □ Female *Student First Name Middle Initial *Student LastName □ Not Provided Racial Identity Hispanic, Latino or Spanish Origin? □ White □ Chinese □ Vietnamese □ Other Pacific Islander □ None □ Cuban □ Other □ Black or African American □ Filipino □ Other Asian □ Samoan □ Mexican, Mexican American, Chicano □ American Indian or Alaska Native □ Japanese □ Native Hawaiian □ Other □ Puerto Rican □ Asian Indian □ Korean □ Guamanian or Chamorro *Date of Birth (month, day, year) *Social Security Number Student Test Number (STN) *Mailing Address (number and street) IN *City State *ZIP Code *County Type □ Cell □ Home *E-mail Address *Telephone Number □ Work Current Middle School High School Student Will Attend Student’s 21st Century Scholars Pledge For application to be considered, a student must agree to the following pledge by signing below. -

Asia and Japan in the 21St Century—The Decade of the 2000S

This article was translated by JIIA from Japanese into English as part of a research project to promote academic studies on Japan’s diplomacy. JIIA takes full responsibility for the translation of this article. To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your personal use and research, please contact JIIA by e-mail ([email protected]). Citation: Japan’s Diplomacy Series, Japan Digital Library, http://www2.jiia.or.jp/en/digital_library/japan_s_diplomacy.php Asia and Japan in the 21st Century —The Decade of the 2000s* Taizo Miyagi Once characterized by war, conflict, and poverty, Asia had transformed itself into a region of remarkable economic growth and development by the end of the 20th century. This in fact was what Japan had hoped and striven for Asia throughout the postwar period. However, the emergence of China and other devel- opments have eclipsed Japan’s presence in Asia, so that Japan can no longer claim an unchallenged posi- tion even in economic matters. While 21st century Asia stands proud as the growth center for the world economy, there are undeniable signs that this region is becoming the stage for a new power game that is now unfolding. How is Japan to live and prosper in this environment? In the final analysis, the 21st cen- tury signifies the advent of a new age that can no longer be understood in terms of the “postwar” construct. I. The Koizumi Cabinet and Asia 1. Breaking Free of Conventional Wisdom with Bold Actions Before assuming the post of prime minister, Junichiro Koizumi was long considered to be a maverick within a Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) dominated by the Keiseikai Group (Takeshita Faction), which claimed the postal business lobby as a powerful source of support. -

REN21 Renewables 2010 Global Status Report

GSR_2010_final 14.07.2010 12:23 Uhr Seite 1 GSR_2010_final 27.09.2010 16:13 Uhr Seite 2 2 RENEWABLES 2010 GLOBAL STATUS REPORT Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century REN21 convenes international multi-stakeholder leadership to enable a rapid global transition to renewable energy. It pro- motes appropriate policies that increase the wise use of renewable energies in developing and industrialized economies. Open to a wide variety of dedicated stakeholders, REN21 connects governments, international institutions, nongovernmental organizations, industry associations, and other partnerships and initiatives. REN21 leverages their successes and strengthens their influence for the rapid expansion of renewable energy worldwide. REN21 Steering Committee Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber Hans-Jorgen Koch Mark Radka Ministry of Foreign Affairs Danish Energy Agency Division of Technology, Industry and Economics United Arab Emirates Ministry of Climate and Energy United Nations Environment Programme Denmark Corrado Clini Peter Rae Ministry for the Environment and Territory Li Junfeng World Wind Energy Association/ Italy National Development and Reform Commission, International Renewable Energy Alliance Energy Research Institute/ Chinese Renewable Robert Dixon Energy Industries Association Tineke Roholl Climate and Chemicals Team China Ministry of Foreign Affairs Global Environment Facility The Netherlands Bindu Lohani Michael Eckhart Asian Development Bank Athena Ronquillo Ballesteros American Council on Renewable Energy World Resources Institute/ Ernesto -

Conflict and Violence in the 21St Century Current Trends As Observed in Empirical Research and Statistics

CONFLICT AND VIOLENCE IN THE 21ST CENTURY CURRENT TRENDS AS OBSERVED IN EMPIRICAL RESEARCH AND STATISTICS Mr. Alexandre Marc, Chief Specialist, Fragility, Conflict and Violence World Bank Group In the 21st century, conflicts have increased sharply since 2010 Global trends in armed conflict, 1946-2014 120000 100000 80000 60000 40000 * 20000 0 Battle-related deaths Terrorist casualties Source: Center for Systemic Peace 2014 Source: Uppsala Conflict Database and Global Terrorism Database • In 2015 the number of ongoing conflicts increased to 50 compared to 41 in 2014 (Institute of Economics and Peace) 2 Battle deaths are now largely concentrated in Middle East Source:Gates et. al. “Trends in Armed Conflict, 1946-2014.” (PRIO Conflict Trends, January 2016). 3 World record in forced displacement since WWII Conflicts are increasingly affecting civilians Source: Center for Systemic Peace 2014 Interpersonal violence and gang violence kill much more people than political violence • Interpersonal violence exacts a high human cost Interpersonal violence and political violence tend to be increasingly interrelated, particularly where institutions are weak and social norms have become tolerant of violence. Source: Center for Systemic Peace 2014 6 Interpersonal violence seems to be declining but remains very high in some regions Source: Global status report on violence prevention 2014 Source: UNODC Global Study on Homicide Gender based violence remains very high, with negative consequences for both societies and economies • 1 in 3 women in the world -

Iraq War? Current Situation and Issues for Congress

Order Code RL31715 Report for Congress Received through the CRS Web Iraq War? Current Situation and Issues for Congress Updated February 26, 2003 Raymond W. Copson (Coordinator) Specialist in International Relations Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Trade Division Congressional Research Service ˜ The Library of Congress Iraq War? Current Situation and Issues for Congress Summary On November 8, 2002, the United Nations Security Council, acting at U.S. urging, adopted Resolution 1441, giving Iraq a final opportunity to “comply with its the disarmament obligations” or “face serious consequences.” During January and February 2003, the U.S. military buildup in the Persian Gulf continued, and analysts speculated that mid-March seemed the most likely time for U.S. forces to launch a war. President Bush, other top U.S. officials, and British Prime Minister Tony Blair have repeatedly indicated that Iraq has little time left to offer full cooperation with U.N. weapons inspectors. However, leaders of France, Germany, Russia, and China, are urging that the inspections process be allowed more time. The Administration asserts that Iraq is in defiance of 17 Security Council resolutions requiring that it fully declare and eliminate its weapons of mass destruction (WMD). Skeptics, including many foreign critics, maintain that the Administration is exaggerating the Iraqi threat. In October 2002, Congress authorized the President to use the armed forces of the United States to defend U.S. national security against the threat posed by Iraq and to enforce all relevant U.N. resolutions regarding Iraq (P.L. 107-243). Some Members of Congress have expressed dissatisfaction with the level of Administration consultation on Iraq, and suggested that the Administration should provide more information on why Iraq poses an immediate threat requiring early military action. -

How Can the 2020S Be a Progressive Decade?

ACTION PAPER HOW CAN THE 2020S BE A PROGRESSIVE DECADE? BY GEOFF MULGAN #pgs21 progressive-governance.eu HOW CAN THE 2020S BE A PROGRESSIVE DECADE? #pgs21 How can the 2020s be a progressive decade? by Geoff Mulgan n recent years progressives have been embat- third way, full-blooded socialism, tighter discipline, I tled. In many countries they have clung to a better communications ...all would be fine. This shrinking centre-ground – often defending glo- piece suggests some different ways to respond: balisation despite its evident failings, uncertain how to respond to new patterns of inequality, • Renew the central idea of being progres- struggling to address threatened feelings of sive – the view that the best years lie ahead, belonging, and squeezed into defense of past not behind; achievements against attacks rather than offering much vision of the future. • Translate that into programmes that are ambitious and engaging (on jobs and life- The result has been a narrowing of ambition and time learning, care services and housing, an emotional hollowing out that has left pro- climate justice and democracy); gressive parties cool, technocratic and unexciting and without either a compelling explanation of • Use these to grow broad coalitions; how to the present or a roadmap for the future. Even as adopt a new philosophy of how to govern; disastrous a President as Trump was only just and how to rethink political style and cul- defeated and would probably have won had it ture in a social media era. not been for the pandemic. The central argument is that progressive poli- Many analyses extrapolate from these problems tics has to offer both practical policies for the and predict inevitable decline.