A Crisis of Identity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chwa Nima Ab'aj ( Mixco Viejo)

1 2 Chwa Nima Ab’aj ( Mixco Viejo) “Recordación Florida”, o, “Historia del Reyno de Goathemala”, es una obra escrita por el Capitán Francisco Fuentes y Guzmán en 1690, o sea unos 165 años después de que fuerzas invasoras españolas ocuparan el territorio de la actual Guatemala. A Fuentes y Guzmán se le considera el primer historiador criollo guatemalteco, ya que en esta obra narra lo que se acredita como la primera historia general del país. Por los cargos ocupados: Cronista de Ciudad nombrado por el Rey, Regidor Perpetuo del Ayuntamiento y Alcalde Mayor tuvo acceso a numerosos documentos (muchos desaparecidos) que le permitió hacer esa monumental obra. Hoy día, con la aparición de otros antiguos documentos con narraciones tanto de indígenas, como de españoles y mestizos, algunos de los datos y hechos consignados en la famosa “Recordación Florida” han sido refutados, negados o impugnados, sin que por esos casos se ponga en cuestión la trascendencia de la obra del “Cronista de la Ciudad”. Esta obra es de capital importancia pues en ella se consigna por vez primera la existencia de Mixco, (Chwa Nima Ab’aj) así como los sucesos acaecidos en la batalla que finalizó con su destrucción por parte de los españoles. Sin embargo, a pesar de la autenticidad narrativa de Fuentes y Guzmán sobre la batalla librada para ocupar Mixco, el nombre que le dio a esta inigualable ciudadela ceremonial, así como los datos sobre la etnia indígena que la habitaba y defendió ante la invasión española, los Pokomames, han sido impugnados sobre la base de estudios antropológicos, arqueológicos y documentos indígenas escritos recién terminada la conquista. -

Eta Y Iota En Guatemala

Evaluación de los efectos e impactos de las depresiones tropicales Eta y Iota en Guatemala México Belice Petén Huehuetenango Guatemala Quiché Alta Verapaz Izabal Baja Verapaz San Marcos Zacapa Quetzaltenango Chiquimula Honduras Guatemala Sololá Suchitepéquez Jutiapa Escuintla El Salvador Nicaragua Gracias por su interés en esta publicación de la CEPAL Publicaciones de la CEPAL Si desea recibir información oportuna sobre nuestros productos editoriales y actividades, le invitamos a registrarse. Podrá definir sus áreas de interés y acceder a nuestros productos en otros formatos. www.cepal.org/es/publications Publicaciones www.cepal.org/apps Evaluación de los efectos e impactos de las depresiones tropicales Eta y Iota en Guatemala Este documento fue coordinado por Omar D. Bello, Oficial de Asuntos Económicos de la Oficina de la Secretaría de la Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), y Leda Peralta, Oficial de Asuntos Económicos de la Unidad de Comercio Internacional e Industria de la sede subregional de la CEPAL en México, en el marco de las actividades del Programa Ordinario de Cooperación Técnica implementado por la CEPAL. Fue preparado por Álvaro Monett, Asesor Regional en Gestión de Información Geoespacial de la División de Estadísticas de la CEPAL, y Juan Carlos Rivas y Jesús López, Oficiales de Asuntos Económicos de la Unidad de Desarrollo Económico de la sede subregional de la CEPAL en México. Participaron en su elaboración los siguientes consultores de la CEPAL: Raffaella Anilio, Horacio Castellaro, Carlos Espiga, Adrián Flores, Hugo Hernández, Francisco Ibarra, Sebastián Moya, María Eugenia Rodríguez y Santiago Salvador, así como los siguientes funcionarios del Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo (BID): Ginés Suárez, Omar Samayoa y Renato Vargas, y los siguientes funcionarios del Banco Mundial: Osmar Velasco, Ivonne Jaimes, Doris Souza, Juan Carlos Cárdenas y Mariano González. -

Plan-Maestro-2015-2025.Pdf

PLAN MAESTRO DE TURISMO SOSTENIBLE DE GUATEMALA 2015 - 2025 PLAN MAESTRO DE TURISMO SOSTENIBLE DE GUATEMALA 2015 - 2025 PLAN MAESTRO DE TURISMO SOSTENIBLE DE GUATEMALA 2015 - 2025 PLAN MAESTRO DE TURISMO SOSTENIBLE DE GUATEMALA 2015 - 2025 Prólogo Guatemala es un destino cultural único, con una constituye un compromiso de nación para el historia que se remonta a más de 3500 años, desarrollo competitivo. que se evidencia en sitios monumentales de la Civilización Maya, así como con 3 sitios declarados Este Plan, es una visión compartida del sector público Patrimonio Mundial por la UNESCO; es un país rico y privado, que orientará el desarrollo sostenible en manifestaciones culturales y tradiciones con 22 del turismo para los próximos diez años, lo cual etnias Mayas, Garífuna y Xinca. Su entorno natural ha sido posible, gracias al liderazgo del Instituto megadiverso, lo componen 7 biomas, 14 zonas de Guatemalteco de Turismo, al decidido apoyo de la vida, más de 300 microclimas, con un 31.04% del Organización Mundial de Turismo sector privado territorio nacional como reserva protegida. turístico organizado y al esfuerzo y experiencia de diversos actores. Aunado a la hospitalidad de su gente, el país brinda condiciones inigualables para consolidar al turismo Mientras la Política ha creado el marco general de como una alternativa eficaz e incluyente para el acción a través de ocho ejes estratégicos, el Plan combate a la pobreza, a través de más y mejores establece y prioriza, de manera integral, el rumbo de empleos, especialmente en micro, pequeñas y la industria turística y se constituye en un articulador medianas empresas. -

Public Space and a Marketplace at Tenam Puente, Chiapas, Mexico La Construcción De Una Plaza: Espacios Públicos Y Áreas De Mercado En Tenam Puente, Chiapas, México

ESTUDIOS DE CULTURA MAYA LVIII: 45-83 (OTOÑO-INVIERNO 2021) The Making of a Plaza: Public Space and a Marketplace at Tenam Puente, Chiapas, Mexico La construcción de una plaza: espacios públicos y áreas de mercado en Tenam Puente, Chiapas, México ELIZABETH H. PARIS Universidad de Calgary, Canadá RobeRto López bRavo Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, México GabRieL LaLó Jacinto Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Centro Chiapas, México ABSTRACT: This study investigates the shifting meanings and practices inscribed on the Main Plaza at the ancient Maya city of Tenam Puente. Plazas are fundamental features of ancient Mesoamerican cities that were important sites for civic activities such as mass spectacles, ceremonies, private rituals, feasting. More recently, certain plazas have also been documented as permanent or periodic marketplaces. New radiocarbon dates and stratigraphic test excavations provide evidence for several important transformations in the built landscape of Tenam Puente’s Main Plaza, including renovations to the site’s principal ballcourt, a large filling and resurfacing event, and a significant addition to the plaza’s volume for the purpose of building a semi-enclosed marketplace plaza. These results provide insight into the evolving nature of public space at the site, from a focus on private rituals and dynastic rule, to an emphasis on mass spectacle, commercial activity, and civic engagement. KEY WORDS: Chiapas; Maya; Tenam Puente; chronology; plaza; marketplace. RESUMEN: El presente estudio investiga los cambiantes significados y prácticas ins- critas en la Plaza Principal de la antigua ciudad maya de Tenam Puente. Las plazas son elementos arquitectónicos fundamentales en las antiguas ciudades mesoame- PARIS, LÓPEZ Y LALÓ / THE MAKING OF A PLAZA AT TENAM PUENTE 45 ricanas que fueron sitios importantes para actividades cívicas como espectáculos, ceremonias, rituales privados y banquetes. -

Complicada Marañas Políticas En La Batalla De Las Aspiraciones

JULIO 2003 EL FARO 1 AÑO 5 EDICIÓN 42 CABO ROJO JULIO 2003 GRATIS Complicada marañas políticas en la batalla de las aspiraciones populares y penepeístas el público respaldo de Pérez y con quien como funcionario municipal para unirse trabajó arduamente, y Eduardo Burgos, al personal administrativo de campaña quien también tiene el respaldo abierto de la oficina del senador por el Distrito del alcalde de San Germán, Isidro Mayagüez-Aguadilla, licenciado Rafael Negrón. Otros nombres barajeados con Irizarry Cruz. De igual manera, se tuvo posibilidades de radicar sus candidaturas conocimiento de la renuncia de Ramírez antes del 1 de agosto son la profesora Rivera, aspirante al escaño del Distrito Evelyn Alicea e Israel Rivera. También #20 por el PNP de la posición que se hizo mención de las posibilidades de ocupaba en la administración de Padilla postulación del hermano del fenecido Ferrer. senador Jorge Alberto Ramos Comas, El representante Harry Luis Pérez René Ramos Comas, y del ex candidato aseguró que Bianchi, a quien respalda a la alcaldía de Cabo Rojo, Luis Enrique como su sucesor, ha sido un fiel empleado Ojeda Martínez. El primero, según se Carlos Segarra Emilio Carlo Acosta Por Reinaldo Silvestri Ferrer, quien hasta el momento no ha sido El Faro retado a procesos primaristas internos. De igual manera, se ha hecho mención de la En el complicado drama de las posibilidad de postulación por el mismo postulaciones para la Cámara de distrito representativo de la profesora Representantes como la Poltrona Maureen Marchany y del comerciante Municipal caborrojeña, a esta fecha Edobel Santiago. se han fortalecido las posibilidades de En cuanto a las aspiraciones a la Casa triunfo de algunos aspirantes, otros han del Pueblo por parte de las filas rojas, declinado mantenerse en el proceso, y figuran como candidatos Emilio Carlo varios o están en un estado de indecisión Acosta, quien preside la colectividad; al o sencillamente sus posibilidades igual que el licenciado Nelson Vincenty Lcdo. -

Maya Skeletal Remains from the Copan and El Puente Sites in Honduras YUJI MIZOGUCHI1*, SEIICHI NAKAMURA2

ANTHROPOLOGICAL SCIENCE Vol. 114, 75–88, 2006 Maya skeletal remains from the Copan and El Puente sites in Honduras YUJI MIZOGUCHI1*, SEIICHI NAKAMURA2 1Department of Anthropology, National Science Museum, 3-23-1 Hyakunin-cho, Shinjuku-ku, Tokyo, 169-0073 Japan 2Copan Archaeological Project, Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History, Copan Ruins, Honduras Received 31 March 2004; accepted 29 March 2005 Abstract The permanent teeth of two individuals from the 10J-45 compound in the Classic Maya site of Copan, Honduras, and the whole skeletons of two individuals from the El Puente site, a secondary Maya center of Copan, were morphologically observed and measured. Preliminary analyses of the well-preserved permanent teeth of the two El Puente individuals show that one is closest to Native South Americans and the other to Native North Americans. Although many human skeletal remains have already been excavated at these two sites, they have not fully been studied. In addition, many other archaeological sites in Honduras also remain to be investigated. Key words: skull, permanent teeth, postcranial skeleton, Q-mode correlation, Native Americans Introduction centers (Fash, 2001), and the El Puente site, a secondary Maya center (Nakamura, 1996). At the Copan site, some Many Maya archaeological sites have been found in the hundreds of skeletal remains have been uncovered up to the area of southeastern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, western present (Maca and Rhoads, 2002). At least one series of Honduras, and western El Salvador. The most flourishing skeletal remains was excavated in 1938 and 1939, though period of the Maya civilization is called the Classic period, these were badly preserved (Longyear, 1940), and another which lasted from 250 to 900 AD. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

LOS OTROS KAQCHIKELES: LOS CHAJOMA VINAK Roberc M. Hill 11* Resumen Los chajomá eran una entidad política iiriportanre de habla kaqchikel durante el posclásico tardío. Un pequefio conjunto de documentos del siglo XVI nos permite identificar los orígenes de los chajomá, aproximar el momento de su llegada a su terrirorio histórico y definir su extensión. Junto con datos arqueológicos, podemos caracterizar la organización y calcular el total de su población de manera provisional. Abstract THEOTHER KAQCHIKEL: THE CHAIOMA VINAK Duririg the Late Postclassic the Chajomá were an important political segment of rhe Kaqchikel-speaking population. A small collection of documents from the sixteenth century allows us to identify the Chajomás' origins, to establish approximately when rhey arrived at their historical territory, and to define rhe size of their region. Comhined ivith archaeological findings, we are able to describe the group's oganization and to make a provisional calculation of their total population size. El presente informe se enfoca en los antiguos hablantes del idioma kaqchikel a quienes se les refiere consistentemente en los Anales de lmXzhilo CüschiqueIer como los akajal vinak. Ellos mismos se denominaban los Chajo-má. Probablemente sean los mismos a quienes se menciona en el Popol Vuh como los &u1 vinak (siendo akul la versión k'iche' de akajalen kaqchikel, palabras que en ambos idiomas quieren decir "colmena"). Desafortuna-damente, los antiguos señores de esta nación no escribieron (o, por lo menos, desconocemos) una historia tan amplia o detallada como el Popol Vuh o los AizaIes. Por eso, conocemos con frustración poco de su historia y composición socio-política. -

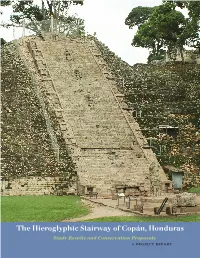

Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán, Honduras

The Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán, Honduras Study Results and Conservation Proposals The Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán,a project Honduras report Study Results and Conservation Proposals a project report The Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán, Honduras The Hieroglyphic Stairway of Copán, Honduras Study Results and Conservation Proposals a project report The Getty Conservation Institute, Los Angeles Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia, Tegucigalpa Copyright © 2006 J. Paul Getty Trust and Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia Design: Joe Molloy, Mondo Typo, Inc. Every effort has been made to contact the copyright holders of the material in this book and to obtain permission to publish. Any omissions will be corrected in future volumes if the publisher is notified in writing. Getty Conservation Institute 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 700 Los Angeles, CA 90049-1684, United States Telephone 310 440-7325 Fax 310 440-7702 E-mail [email protected] www.getty.edu/conservation Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia Villa Roy Barrio Buenos Aires Tegucigalpa, Apartado 1518, Honduras Telephone 504 222-3470 Fax 504 222-2552 E-mail [email protected] www.ihah.hn/ The Getty Conservation Institute works internationally to advance the field of conservation through scientific research, field projects, education and training, and the dissemination of information in various media. In its programs, the gci focuses on the creation and delivery of knowledge that will benefit the professionals and organizations responsible for the conserva- tion of the visual arts. The Instituto Hondureño de Antropología e Historia (ihah) is an autonomous agency of the Honduran state charged with protecting, conserving, and researching the cultural heritage of Honduras. -

March 2001 Japan International Cooperation

No. STUDY REPORT ON THE PROJECT FOR IMPROVEMENT OF EQUIPMENT FOR ARCHAEOLOGICAL ACTIVITIES ON MAYA CIVILIZATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF HONDURAS MARCH 2001 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) G R 2 CR (1) 01 - 091 CONTENTS PREFACE LOCATION MAP CHAPTER 1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT--------------------------------------------------1 CHAPTER 2 CONTENTS OF THE PROJECT -------------------------------------------------------4 2.1 Basic Concept of the Project ------------------------------------------------------------------------4 2.2 Basic Design for Requested Japanese Assistance------------------------------------------------6 2.2.1 Design Policy -----------------------------------------------------------------------------7 2.2.2 Basic Plan (Equipment Plan) -----------------------------------------------------------8 2.2.3 Implementation Plan ------------------------------------------------------------------- 25 2.3 Obligations of Recipient Country ---------------------------------------------------------------- 28 2.4 Project Operation Plan ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 30 CHAPTER 3 PROJECT EVALUATION AND RECOMMENDATIONS---------------------- 31 3.1 Project Effects--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 31 3.2 Recommendations ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 35 APPENDICES 1. Member List of the Study Team--------------------------------------------------------------------- 39 2. Study Schedule----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

Inventario Nacional De Los Humedales De Guatemala / Editores Margareth Dix, Juan F

UICN - La Unión Mundial para la Naturaleza fue fundada en 1948 Consejo Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONAP) y reúne a 79 estados, 112 dependencias gubernamentales, 760 ONG, 37 afiliados y unos 10.000 científicos y expertos procedentes El CONAP, es una entidad pública, que depende de la de 181 países en una asociación mundial única. Su misión es de Presidencia de la República , establecida en el año de 1989, Inventario Nacional de los Humedales Guatemala influenciar, alentar y ayudar a las sociedades de todo el mundo a regula sus actuaciones según lo establecido en la Ley de Áreas conservar la integridad y diversidad de la naturaleza, y asegurar Protegidas (Decreto 4-89, y sus reformas). Es el órgano máximo que cualquier utilización de los recursos naturales se haga de de dirección y coordinación del Sistema Guatemalteco de Áreas manera equitativa y ecológicamente sostenible. Dentro del marco Protegidas -SIGAP-, con jurisdicción en todo el territorio de los convenios mundiales de conservación, la UICN promueve nacional, sus costas marítimas y su espacio aéreo. la sostenibilidad y ha ayudado a más de 75 países a preparar e implementar estrategias nacionales de la conservación y de la El propósito del CONAP, es asegurar la conservación de niveles diversidad biológica. La UICN es una organización global que socialmente deseables de diversidad biológica (ecosistemas, cuenta con unos 1.000 empleados en 42 países, cien de los especies y material genético), a través de las áreas protegidas y Inventario cuales trabajan en su sede de Gland, Suiza. otros mecanismos de conservación in situ y ex situ, y asegurar la generación de servicios ambientales, para el desarrollo social UICN / Mesoamérica – Oficina Regional para Mesoamérica y económico sostenible de Guatemala y el beneficio de las presentes y futuras generaciones. -

Asociaciones Inscritas

ASOCIACIONES INSCRITAS No. Partida Folio Libro Nombre Entidad Fecha Inscripción 1 31 31 1 Asociación que se denomina "ALAS DE AGUILA" 26/07/2006 2 32 32 1 de Vecinos del Residencial Naciones Unidas Dos 26/07/2006 3 33 33 1 CIVIL RED REGIONAL DE JUSTICIA Y PAZ 26/07/2006 4 34 34 1 NACIONAL DE EMPLEADOS MUNICIPALES A.N.E.M. 26/07/2006 5 35 35 1 DE DESARROLLO COMUNITARIO 26/07/2006 6 38 38 26/07/2006 1 DE JUBILADOS MUNICIPALES CHINAUTLA "AJ-MUNICH" 7 64 64 1 de Desarrollo para el Progreso 31/07/2006 8 66 66 01/08/2006 1 ASOCIACION PRO FORTALECIMIENTO DE LA JUSTICIA 9 67 67 01/08/2006 1 CATOLICA RESIDENCIAL LOS OLIVOS DE GUATEMALA 10 68 68 1 DE MICROBUCEROS LOS LACANDONES. 01/08/2006 11 95 95 01/08/2006 1 ASOCIACION DE TRANSPORTISTAS LINDA SANTA TERESA 12 96 96 ASOCIACION CIVIL ESTEREO RENOVACION CARISMATICA 01/08/2006 1 ESPIRITU SANTO 13 99 99 01/08/2006 1 DE CRIMINOLOGOS Y CRIMINALISTAS DE GUATEMALA 14 103 103 1 EVANGELICA NAZARENA BELLO HORIZONTE 02/08/2006 15 104 104 1 SHALOM 02/08/2006 16 105 105 1 INTEGRAL BASE SOLIDA 02/08/2006 17 134 134 ASOCIACIÓN CIVIL DE MUJERES UN NUEVO DÍA, SECTOR 02/08/2006 1 CHAPINAS, SAN LORENZO SUCHITEPEQUEZ. 18 137 137 02/08/2006 1 ASOCIACION CLUB DEPORTIVO LANQUIN (ASODERSA) 19 138 138 ASOCIACION INTEGRAL DE CRIADORES DE POLLOS DE 02/08/2006 1 ENGORDE DE SAN CRISTOBAL ACASAGUASTLAN 20 140 140 DE GANADEROS Y AGRICULTORES DE SAN JERONIMO, 02/08/2006 1 BAJA VERAPAZ (AGASANJE). -

Demos a La Niñez Un Futuro De Paz

libro niñez 1 A.FH10 Mon Jun 25 02:18:11 2007 Page 1 Demos a la Niñez Un Futuro de Paz OFICINA DE DERECHOS ODHAG HUMANOS DEL ARZOBISPADO DE GUATEMALA Composite libro niñez 1 A.FH10 Mon Jun 25 02:18:11 2007 Page 2 OFICINA DE DERECHOS HUMANOS DEL ARZOBISPADO DE GUATEMALA Dirección: 6a. calle 7-70 zona 1 Guatemala, Guatemala, C.A. PBX: (502) 2285-0456 Fax: (502) 2232-8384 Correo Electrónico: [email protected] Guatemala, Abril 2006 Monseñor Gonzalo de Villa s.j. Coordinador General Nery Estuardo Rodenas Director Ejecutivo Carlos Alarcón Novoa Coordinador del Area de Cultura de Paz Miriam Lemus Investigación y Redacción Arturo Aguilar Consejo Editorial Carolina Rendón Patricia Ogaldes Ninfa Alarcón Oscar Reyes Cristian Ozaeta Paola Godoy Claudia Agreda Celia Ovalle Apoyo Técnico y Redacción Gustavo Ortiz Diseño de Portada Tinta y Papel Impresión Esta publicación se realizó gracias al apoyo de DIAKONIA y MISEREOR. Composite libro niñez 1 A.FH10 Mon Jun 25 02:18:11 2007 Page 3 AGRADECIMIENTOS Durante la investigación se realizaron acercamientos a diversas instituciones que nos abrieron las puertas proporcionando información acerca de la niñez víctima y participando en esta publicación, ellas son: Hijos e Hijas por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio, H.I.J.O.S. Familiares de Desaparecidos de Guatemala, FAMDEGUA Asociación ¿Dónde Están los Niños y las Niñas? Centro de Análisis Forense y Ciencias Aplicadas, CAFCA Equipo de Estudios Comunitarios y Análisis Psicosocial, ECAP Asociación Utz K'aslemal Paz y Reconciliación de Pastoral Social de la Diócesis de El Quiché Grupo de Apoyo Mutuo, GAM Comisión Nacional de Búsqueda de Niñez Desaparecida CNBND Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala, FAFG Centro Maya Saqb'e Conferencia Nacional de Ministros de la Espiritualidad Maya Composite libro niñez 1 A.FH10 Mon Jun 25 02:18:11 2007 Page 4 Composite libro niñez 1 A.FH10 Mon Jun 25 02:18:11 2007 Page 5 CONTENIDO Homenaje a la memoria .......................................................................................