R. Needham Mourning-Terms In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal-, Land- En

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 405 265 SO 026 916 TITLE Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program: Malaysia 1995. Participants' Reports. INSTITUTION Center for International Education (ED), Washington, DC.; Malaysian-American Commission on Educational Exchange, Kuala Lumpur. PUB DATE 95 NOTE 321p.; Some images will not reproduce clearly. PUB TYPE Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) Reports Descriptive (141) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Area Studies; *Asian History; *Asian Studies; Cultural Background; Culture; Elementary Secondary Education; Foreign Countries; Foreign Culture; *Global Education; Human Geography; Instructional Materials; *Non Western Civilization; Social Studies; *World Geography; *World History IDENTIFIERS Fulbright Hays Seminars Abroad Program; *Malaysia ABSTRACT These reports and lesson plans were developed by teachers and coordinators who traveled to Malaysia during the summer of 1995 as part of the U.S. Department of Education's Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Program. Sections of the report include:(1) "Gender and Economics: Malaysia" (Mary C. Furlong);(2) "Malaysia: An Integrated, Interdisciplinary Social Studies Unit for Middle School/High School Students" (Nancy K. Hof);(3) "Malaysian Adventure: The Cultural Diversity of Malaysia" (Genevieve M. Homiller);(4) "Celebrating Cultural Diversity: The Traditional Malay Marriage Ritual" (Dorene H. James);(5) "An Introduction of Malaysia: A Mini-unit for Sixth Graders" (John F. Kennedy); (6) "Malaysia: An Interdisciplinary Unit in English Literature and Social Studies" (Carol M. Krause);(7) "Malaysia and the Challenge of Development by the Year 2020" (Neale McGoldrick);(8) "The Iban: From Sea Pirates to Dwellers of the Rain Forest" (Margaret E. Oriol);(9) "Vision 2020" (Louis R. Price);(10) "Sarawak for Sale: A Simulation of Environmental Decision Making in Malaysia" (Kathleen L. -

The Response of the Indigenous Peoples of Sarawak

Third WorldQuarterly, Vol21, No 6, pp 977 – 988, 2000 Globalizationand democratization: the responseo ftheindigenous peoples o f Sarawak SABIHAHOSMAN ABSTRACT Globalizationis amulti-layered anddialectical process involving two consequenttendencies— homogenizing and particularizing— at the same time. Thequestion of howand in whatways these contendingforces operatein Sarawakand in Malaysiaas awholeis therefore crucial in aneffort to capture this dynamic.This article examinesthe impactof globalizationon the democra- tization process andother domestic political activities of the indigenouspeoples (IPs)of Sarawak.It shows howthe democratizationprocess canbe anempower- ingone, thus enablingthe actors to managethe effects ofglobalization in their lives. Thecon ict betweenthe IPsandthe state againstthe depletionof the tropical rainforest is manifested in the form of blockadesand unlawful occu- pationof state landby the former as aform of resistance andprotest. Insome situations the federal andstate governmentshave treated this actionas aserious globalissue betweenthe international NGOsandthe Malaysian/Sarawakgovern- ment.In this case globalizationhas affected boththe nation-state andthe IPs in different ways.Globalization has triggered agreater awareness of self-empow- erment anddemocratization among the IPs. These are importantforces in capturingsome aspects of globalizationat the local level. Globalization is amulti-layered anddialectical process involvingboth homoge- nization andparticularization, ie the rise oflocalism in politics, economics, -

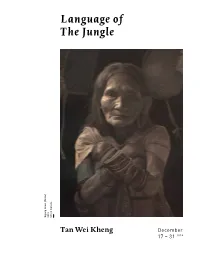

Language of the Jungle

Language of The Jungle Oil on Canvas Sigang Kesei (Detail) Sigang Kesei 2013 Tan Wei Kheng December 17 – 31 2014 Has the jungle become more beautiful? The artist Tan Wei Kheng paints portraits of the unseen heroes of the nomadic Penan tribe in Sarawak, Malaysia. He invites us to discover the values and dreams of the Penans, who continue with their struggles in order to live close to nature. Tan is also involved in other initiatives and often brings with him rudimentary Language Of supplies for the Penans such as rice, sugar, tee shirts, and toothpaste. As natural – Ong Jo-Lene resources are destroyed, they now require supplements from the modern world. The Jungle Kuala Lumpur, 2014 Hunts do not bear bearded wild pigs, barking deers and macaques as often anymore. Now hunting takes a longer time and yields smaller animals. They fear that the depletion of the tajem tree from which they derive poison for their darts. The antidote too is from one specific type of creeper. The particular palm tree that provides leaves for their roofs can no longer be found. Now they resort to buying tarpaulin for roofing, which they have to carry with them every time they move Painting the indigenous peoples of Sarawak is but one aspect of the relationship from camp to camp. Wild sago too is getting scarcer. The Penans have to resort to that self-taught artist, Tan Wei Kheng has forged with the tribal communities. It is a farming or buying, both of which need money that they do not have. -

Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key?

sustainability Article Adaptation to Climate Change: Does Traditional Ecological Knowledge Hold the Key? Nadzirah Hosen 1,* , Hitoshi Nakamura 2 and Amran Hamzah 3 1 Graduate School of Engineering and Science, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan 2 Department of Planning, Architecture and Environmental Systems, Shibaura Institute of Technology, Saitama City, Saitama 337-8570, Japan; [email protected] 3 Department of Urban and Regional Planning, Faculty of Built Environment and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai 81310, Johor Bahru, Johor, Malaysia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 25 December 2019; Accepted: 15 January 2020; Published: 16 January 2020 Abstract: The traditional knowledge of indigenous people is often neglected despite its significance in combating climate change. This study uncovers the potential of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) from the perspective of indigenous communities in Sarawak, Malaysian Borneo, and explores how TEK helps them to observe and respond to local climate change. Data were collected through interviews and field work observations and analysed using thematic analysis based on the TEK framework. The results indicated that these communities have observed a significant increase in temperature, with uncertain weather and seasons. Consequently, drought and wildfires have had a substantial impact on their livelihoods. However, they have responded to this by managing their customary land and resources to ensure food and resource security, which provides a respectable example of the sustainable management of terrestrial and inland ecosystems. The social networks and institutions of indigenous communities enable collective action which strengthens the reciprocal relationships that they rely on when calamity strikes. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/29/2021 05:11:55PM Via Free Access 174 Bibliography

Bibliography Ahmed, Sara 1997 ‘Intimate touches; Proximity and distance in international feminist dialogues’, Oxford Literary Review 19:19-46. Alvarez, Claude 1992 Science, development and violence; The revolt against modernity. Delhi: Oxford University Press. Barreirro, J. 1991 ‘Indigenous peoples are the “miners’ canary” of the human family’, in: B. Willers (ed.), Learning to listen to the land, pp. 199-201. Washington DC: Island. Barui, Fraser 2000 ‘Govt serious in helping Penan community’, Sarawak Tribune 16 Sep- tember. Blaikie, Piers and Harold Brookfield 1987 Land degradation and society. London: Methuen. Blowpipes and bulldozers 1988 ‘Blowpipes and bulldozers; A story of the Penan tribe and Bruno Mansur’. [Gaia Films.] Bourdieu, Pierre 1977 Outline of a theory of practice. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1979 Distinction; A social critique of the judgement of taste. Translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Brosius, J. Peter 1986 ‘River, forest and mountain; The Penan Gang landscape’, Sarawak Museum Journal 36:173-89. 1988 ‘A separate reality; Comments on Hoffman’s “The Punan; Hunters and gatherers of Borneo”’, Borneo Research Bulletin 20-2:81-106. 1991 ‘Foraging in tropical rainforests; The case of the Penan of Sarawak, East Malaysia (Borneo)’, Human Ecology 19-2:123-50. 1992 ‘Perspectives on Penan development in Sarawak’, Sarawak Gazette 119- 1:5-22. 1993 ‘Contrasting subsistence ecologies of Eastern and Western Penan foragers (Sarawak, East Malaysia)’, in: C.M. Hladik, A. Hladik, O.F. Linares, H. Pagezy, A. Semple and M. Hadley (eds), Tropical forests, people and food; Biocultural interactions and applications to development, pp. 515-22. -

Keynote Address Human Rights and the Environment: Common Ground

Keynote Address Human Rights and the Environment: Common Ground Kerry Kennedy Cuomot I want to thank Guido Calibresi, Jacki Hamilton, Jacob Scherr, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science for inviting me to Yale today, and I want to thank all of you for coming. As an international human rights attorney, I have focused my efforts on individuals who, in their pursuit of human rights, have stood up to govern- ment oppression at great personal risk. Many of these individuals have been imprisoned, tortured, or killed for their political beliefs. Untold numbers of journalists have been silenced, lawyers jailed, scientists stifled, and trade unionists crushed. What all of these brave individuals have in common is their commitment to justice, non-violence, and the rule of law. Like civil rights lawyers in the United States who look to the Bill of Rights under the Constitution to guide their practice, international human rights lawyers look to a number of international instruments for the laws by which we expect governments to abide. Most human rights norms are based upon the Universal Declaration of Human Rights1 and the International Covenants on human rights.2 The Declaration was signed in 1948 in reaction to the Nazi atrocities during World War II, and set forth principles which members of the United Nations agreed to recognize. The Covenants were drafted and signed a few years later, and they set forth specific rights which states are bound to uphold. If states violate the terms of the CoVenants, they can be brought before a tribunal and held accountable. -

Wood for the Trees: a Review of the Agarwood (Gaharu) Trade in Malaysia

WOOD FOR THE TREES : A REVIEW OF THE AGARWOOD (GAHARU) TRADE IN MALAYSIA LIM TECK WYN NOORAINIE AWANG ANAK A REPORT COMMISSIONED BY THE CITES SECRETARIAT Published by TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia © 2010 The CITES Secretariat. All rights reserved. All material appearing in this publication is copyrighted and may be reproduced with permission. Any reproduction in full or in part of this publication must credit the CITES Secretariat as the copyright owner. This report was commissioned by the CITES Secretariat. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not however necessarily reflect those of the CITES Secretariat. The geographical designations employed in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or its authorities, or concerning the definition of its frontiers or boundaries. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership is held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint programme of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Lim Teck Wyn and Noorainie Awang Anak (2010). Wood for trees: A review of the agarwood (gaharu) trade in Malaysia TRAFFIC Southeast Asia, Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia ISBN 9789833393268 Cover: Specialised agarwood retail shops have proliferated in downtown Kuala Lumpur for the Middle East tourist market Photograph credit: James Compton/TRAFFIC Wood for the trees :A review of the agarwood (gaharu) -

Identity and Eastern Penan in Borneo1

Journal of Modern Languages Vol. 30, (2020) https://doi.org/10.22452/jml.vol30no1.2 Identity and Eastern Penan in Borneo1 Peter Sercombe [email protected] Newcastle University, UK Abstract This paper considers aspects of identity among the Eastern Penan of Borneo, 2 in the approximately half century since many have transitioned from full-time hunting and gathering to a partial or fully sedentary existence, in both Brunei Darussalam (henceforth, Brunei) and East Malaysia. Despite settlement, many Eastern Penan continue to project aspects of hunting and gathering behaviour (at both the individual and community level) through a number of traits such as: social organisation, lifestyle, and nostalgia for the past. Nonetheless, following their move to settlement, there has been more continuous and intense interaction with settled neighbours and state proxies. Through this, Eastern Penan have come to demonstrate identity features that align with neighbours, as well as the nation state in each country, in a number of ways. This paper is based on periods of field work (spanning several decades), in both Brunei and East Malaysia, during a time of considerable change, especially regarding how the physical environment has been exploited in Malaysia. This paper provides a snapshot of Eastern Penan identity which, rather than having fundamentally shifted, appears to have diversified over time as reflected through evolving social circumstances and ways these have impinged on lifestyle, language repertoire, and cultural affiliations among the Eastern Penan. Keywords: Eastern Penan, identity, Borneo, hunter-gatherer, settlement 1 This is a revised, updated and expanded paper, derived from Sercombe (2000). 2 Penan in Sarawak are generally divided between those referred to as ‘Eastern’ or ‘Western’. -

The Indigenous World 2008

THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2008 Copenhagen 2008 THE INDIGENOUS WORLD 2008 Compilation and editing: Kathrin Wessendorf Regional editors: The Circumpolar North & North America: Kathrin Wessendorf Central and South America: Alejandro Parellada Australia and the Pacific: Kathrin Wessendorf Asia: Christian Erni and Mille Lund Africa: Marianne Wiben Jensen International Processes: Lola García-Alix Cover and typesetting: Jorge Monrás Maps: Berit Lund and Jorge Monrás English translation and proof reading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks-Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark © The authors and The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), 2008 - All Rights Reserved The reproduction and distribution of HURRIDOCS CIP DATA information contained in The Indige- Title: The Indigenous World 2008 nous World is welcome as long as the Edited by: Kathrin Wessendorf source is cited. However, the transla- Pages: 578 tion of articles into other languages ISSN: 1024-0217 and the reproduction of the whole ISBN: 9788791563447 BOOK is not allowed without the con- Language: English sent of IWGIA. The articles in The In- Index: 1. Indigenous Peoples – 2. Yearbook – digenous World reflect the authors’ 3. International Processes own views and opinions and not nec- Geografical area: World essarily those of IWGIA itself, nor can Publication date: April 2008 IWGIA be held responsible for the ac- curacy of their content. The Indigenous World is published Distribution in North America: annually in English and Spanish. Transaction Publishers 300 McGaw Drive Director: Lola García-Alix Edison, NJ 08837 Administrator: Anni Hammerlund www.transactionpub.com This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, NORAD, Sida and the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. -

P. Metcalf Birds and Deities in Borneo In: Bijdragen Tot De Taal

P. Metcalf Birds and deities in Borneo In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 132 (1976), no: 1, Leiden, 96-123 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/25/2021 11:07:48PM via free access PETER METCALF BIRDS AND DEITIES IN BORNEO From the earliest days of contact, Western observers have been struck by the deep significance of birds in Bomean religions. Birds are a well- nigh universal feature of religious symbolism, but in Borneo systems of augury are found that are unparalleled in their complexity and in the compelling nature of the omens taken from them. Not only the domain of ritual, but also economie activity, social organisation, even warfare, are in part regulated by them. For those with a classical education, Roman and Greek comparisons immediately suggested themselves. Hose, who wrote extensively about his experiences as an officer of the Brooke regime in Sarawak, tells us that after watching a Kenyah chief call an omen bird he "feit as though I had just lived through a book of the Aeneid" (Hose and McDougall 1912, vol. II: 54). The classical scholar W. Warde Fowler, having stumbled onto Hose's account, developed the comparison further (1920). Despite this early interest, accounts of particular systems of augury are almost entirely lacking, with the exception of Dr. Freeman's pioneer work among the Iban of Western Borneo. The first aim of this paper is to describe another system, that of the Berawan1 of Central North The Berawan are usually, and dubiously, classified as part of the Kenyah tribe. -

CHAGS Programme

the community effects of global climate change, and his regional focus areas include the Workshops and events circumpolar North and the former Soviet Union. He became interested in the hunters and gatherers of Siberia during the 1980s, when their mere existence remained largely unacknowledged for political and typological reasons. CHAGS 7 in Moscow (1993) was among the first major conferences to correct this misconception, and Schweitzer was co-editor of the volume resulting from that meeting, Hunters and Gatherers in the Mod- (E46) Hunter-gatherer resources in the Human Rela- ern World (Berghahn, 2000). Since then, he has been working with Alaskan h unters and tions Area Files (HRAF) gatherers (primarily with Inupiat of Northwest Alaska), as well as continued research in Thursday 26th July, 2:00 – 3:30 PM. Room: SK205 Siberia, with hunters and gatherers and others alike. In 2015, he served as the convenor of CHAGS 11 in Vienna. For extended biography, see https://chags.usm.my/index.php/ Organiser: Alissa Jordan, Human Relations Area Files confprogramme/speakers/peter. Presenter: Teferi Adem, Human Relations Area Files Learn how to find, research, compare, and use ethnographic and archaeological hunter-gatherer research collections in the electronic Human Relations Area Files (eHRAF). Human Relations Area Files (HRAF) has an ever-expanding collec- tion of resources on hunter-gatherers and foragers, with thousands of pages of ethnographic texts about hunter-gatherers, all expertly coded for cross-cultural comparison. This workshop will first briefly introduce participants to the many relevant open access materials on hunter-gatherers located on a hraf.yale.edu, and then demonstrate how to use the full search abilities of eHRAF databases to con- duct powerful research sessions geared exactly to participants’ research interests. -

ART + ARCHITECTURE AUCTION 30 JUNE 2019 LOT 166 IBRAHIM HUSSEIN, DATUK Dark Voices, 1969 LOT 169 SYED AHMAD JAMAL, DATUK Hijrah, 1999

ART + ARCHITECTURE AUCTION 30 JUNE 2019 LOT 166 IBRAHIM HUSSEIN, DATUK Dark Voices, 1969 LOT 169 SYED AHMAD JAMAL, DATUK Hijrah, 1999 LOT 71 AWANG DAMIT AHMAD, E.O.C ‘Hari Kelabu’, 1993 IMPORTANT NOTICE All lots are sold subject to our Conditions of Business printed at the back of this catalogue which apply to both buyers and sellers. Prospective buyers should also read our Buying At HBArt guide. Catalogue descriptions do not state any imperfections. However, condition reports can be obtained by contacting the personnel listed below. This service is provided for the convenience of prospective buyers and cannot be taken as the sole and absolute representation of the actual condition of the work. Prospective buyers are advised to personally examine the works and not rely solely on HBAA’s description on the catalogue or any references made in the conditions reports. Our team will be present during all viewing times and available for consultation regarding artworks included in this auction. Whenever possible, our team will be pleased to provide additional information that may be required. The buyer’s premium shall be 12% of hammer price plus any applicable taxes. All lots from this sale not collected from HBAA seven days after the auction will incur storage and insurance charges, which will be payable by the buyer. CONTACT INFORMATION Polenn Sim Elizabeth Wong General +6016 273 3628 +6013 355 6578 +603 2691 3089 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 2 SPECIAL EDITION ART + ARCHITECTURE AUCTION AUCTION DAY 30 JUNE 2019, 1PM GALERI PRIMA, BALAI BERITA BANGSAR VIEWING 21 - 29 June 2019 Mondays - Sundays 10am - 6pm Galeri Prima, Balai Berita Bangsar 31, Jalan Riong, Bangsar 59100 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia I LIVE ONLINE BIDDING 3 LOT 37 CHUAH THEAN TENG, DATO’, Lullaby, c.