For Solo Cello, Pablo Ortiz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

559288 Bk Wuorinen US

559373-74 bk Lincoln US 12/12/08 12:58 PM Page 16 Also available: AMERICAN CLASSICS ABRAHAM LINCOLN PORTRAITS Ives • Persichetti • Harris • Bacon Gould • McKay • Turok • Copland Nashville Symphony • Leonard Slatkin 8.559328 2 CDs 8.559373-74 16 559373-74 bk Lincoln US 12/12/08 12:58 PM Page 2 ABRAHAM LINCOLN PORTRAITS Also available: CD 1 60:54 1 Charles Ives (1874-1954): Lincoln, the Great Commoner 3:39 2 Vincent Persichetti (1915-1987): A Lincoln Address, Op. 124 13:22 3 Roy Harris (1898-1979): Abraham Lincoln Walks at Midnight 14:10 Ernst Bacon (1898-1990): Ford’s Theatre: A Few Glimpses of Easter Week, 1865 29:43 4 Preamble 1:43 5 Walt Whitman and the Dying Soldier 2:42 6 Passing Troops 2:42 7 The Telegraph Fugue (an Etude for Strings - with Timpani) 5:07 8 Moonlight on the Savannah 2:03 9 The Theatre 1:26 0 The River Queen 2:26 ! Premonitions (a duett with a hall clock) 1:51 @ Pennsylvania Avenue, April 9, 1865 3:35 # Good Friday, 1865 3:15 $ The Long Rain 1:17 % Conclusion 1:35 CD 2 51:43 1 Morton Gould (1913-1996): Lincoln Legend 16:36 George Frederick McKay (1899-1970): To a Liberator (A Lincoln Tribute) 11:18 2 Evocation 3:10 3 Choral Scene 2:49 4 March 2:06 5 Declaration 0:43 6 Epilogue 2:30 7 Paul Turok (b. 1929): Variations on an American Song: Aspects of Lincoln and Liberty, Op. 20 9:18 8 Aaron Copland (1900-1990): Lincoln Portrait 14:31 Publishers: Edwin F. -

Identidade Latino-Americana Na Obra Para Violoncelo De José Bragato

Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Identidade latino-americana na obra para violoncelo de José Bragato Leonardo Medina João Pessoa 2018 Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Identidade latino-americana na obra para violoncelo de José Bragato Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal da Paraíba como requisito parcial para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música, área de concentração Etnomusicologia, linha de pesquisa Música, Cultura e Performance. Leonardo Medina Orientadora: Dra. Alice Lumi Satomi João Pessoa 2018 Un arco capataz sube la cuesta, el arco que dictó, después y antes. Un arco iris bravo y ondulante, sabido de preguntas y respuestas. La gloria enamoró a tu violonchelo, El monumento tuyo es ser tanguista, Y el mío, ser tu hermano, mi Bragato. Horacio Ferrer, Soneto para el mejor en violonchelo y amor. Y así termina el relato de este músico de Udinese Que se escuda en su modestia y es más de lo que parece […] Maestro usted lo merece –y no me haga usted un desaire- Una calle con su nombre necesita Buenos Aires Alberto Francisco Lande, Del piano al chelo Dedicado a José Bragato (in memoriam) e a sua esposa, Gina Lotufo, por tudo o carinho e compreensão para realizar este trabalho. Para meus pais, Suad e Orlando; meus irmãos Sebastián e Federico; meus sobrinhos Valentín, Juan Bautista e Sol; e Inaê; por todo o amor e apoio recebido neste tempo, fazendo possível chegar a cumprir esta meta tão desejada. -

THE BALDWIN PIANO COMPANY * Singing Boys of Norway Springfield (Mo.) Civic Symphony Orchestra St

Music Trade Review -- © mbsi.org, arcade-museum.com -- digitized with support from namm.org Each artist has his own reason for choosing Baldwin as the piano which most nearly approaches the ever-elusive goal of perfection. As new names appear on the musical horizon, an ever-increasing number of them are joining their distinguished colleagues in their use of the Baldwin. Kurt Adler Cloe Elmo Robert Lawrence Joseph Rosenstock Albuquerque Civic Symphony Orchestra Victor Alessandro Daniel Ericourt Theodore Lettvin Aaron Rosand Atlanta Symphony Orchestra Ernest Ansermet Arthur Fiedler Ray Lev Manuel Rosenthal Baton Rouge Symphony Orchestra Claudio Arrau Kirsten Flagstad Rosina Lhevinne Jesus Maria Sanroma Beaumont Symphony Orchestra Wilhelm Bachaus Lukas Foss Arthur Bennett Lipkin Maxim Schapiro Berkshire Music Center and Festival Vladimir Bakaleinikoff Pierre Fournier Joan Lloyd George Schick Birmingham Civic Symphony Stefan Bardas Zino Francescatti Luboshutz and Nemenoff Hans Schwieger Boston "Pops" Orchestra Joseph Battista Samson Francois Ruby Mercer Rafael Sebastia Boston Symphony Orchestra Sir Thomas Beecham Walter Gieseking Oian Marsh Leonard Seeber Brevard Music Foundation Patricia Benkman Boris Goldovsky Nino Martini Harry Shub Burbank Symphony Orchestra Erna Berger Robert Goldsand Edwin McArthur Leo Sirota Central Florida Symphony Orchestra Mervin Berger Eugene Goossens Josefina Megret Leonard Shure Chicago Symphony Orchestra Ralph Berkowitz William Haaker Darius Milhaud David Smith Pierre Bernac Cincinnati May Festival Theodor Haig -

Entrevista Antonio Agri Antonio Agri

Entrevista Antonio Agri Antonio Agri: Es muy difícil en Argentina, la Argentina es muy difícil. Entrevistadora: ¿Y por qué cambió? ¿Por Menem? ¿por todo el gobierno? ¿eso? Antonio Agri: No, no, nunca. Siempre, antes de Menem también, si con Piazzolla hemos sufrido horrores. Nosotros con Piazzolla no trabajábamos nada, nos mordíamos la liebre con Astor, una mentira total. Piazzolla por eso se tuvo que ir también. Entrevistadora: Porque acá no dan plata para la cultura. Antonio Agri: No, aparte es… cuando uno intenta hacer algo que es de cierta calidad no sirve, en este país no sirve. La mediocridad es muy grande, o sea, en Europa también existe la mediocridad. Pero el que vale tiene lugar. Acá el que vale no tiene ningún lugar por eso no hay nadie, o sea, hay gente que se merece estar en algún lugar y no tiene dónde trabajar. Entrevistadora: Por eso ya viajaron a Japón ¿no? Antonio Agri: Sí, fuimos y ya nos contactaron otra vez, pero vamos a lugares, digamos, como si fuera… Allá se sorprendieron todos “¿Pero cómo es un conjunto de cámara?” y va con la noticia, claro. Y tocamos los mismos areglos que se han tocado siempre. La música popular, sacando honrosas excepciones, la cuestión matices, no. Un director de sinfónica acá nos decía:“ No se olviden nunca que los músicos malos tocan fuerte. Solamente músicos buenos tocan bien.” Entrevistadora: Sí, sí. Antonio Agri: Es muy difícil, muy difícil. Bueno, usted dirá. Entrevistadora: Bueno. Yo tengo una pregunta quizás un poco grave, pero yo soy de ascendiente judía y escuché mucho la música klezmer ¿no? Y ahora escuchando el violín en el tango yo me pregunté o me pareció que el estilo o la especie de rubato, de llegar a la nota con glissando me hace recordar mucho la música que conozco allá del este. -

TANGO… the Perfect Vehicle the Dialogues and Sociocultural Circumstances Informing the Emergence and Evolution of Tango Expressions in Paris Since the Late 1970S

TANGO… The Perfect Vehicle The dialogues and sociocultural circumstances informing the emergence and evolution of tango expressions in Paris since the late 1970s. Alberto Munarriz A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN MUSIC YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO March 2015 © Alberto Munarriz, 2015 i Abstract This dissertation examines the various dialogues that have shaped the evolution of contemporary tango variants in Paris since the late 1970s. I focus primarily on the work of a number of Argentine composers who went into political exile in the late 1970s and who continue to live abroad. Drawing on the ideas of Russian linguist Mikhail Bakhtin (concepts of dialogic relationships and polyvocality), I explore the creative mechanisms that allowed these and other artists to engage with a multiplicity of seemingly irreconcilable idioms within the framing concept of tango in order to accommodate their own musical needs and inquietudes. In addition, based on fieldwork conducted in Basel, Berlin, Buenos Aires, Gerona, Paris, and Rotterdam, I examine the mechanism through which musicians (some experienced tango players with longstanding ties with the genre, others young performers who have only recently fully embraced tango) engage with these new forms in order to revisit, create or reconstruct a sense of personal or communal identity through their performances and compositions. I argue that these novel expressions are recognized as tango not because of their melodies, harmonies or rhythmic patterns, but because of the ways these features are “musicalized” by the performers. I also argue that it is due to both the musical heterogeneity that shaped early tango expressions in Argentina and the primacy of performance practices in shaping the genre’s sound that contemporary artists have been able to approach tango as a vehicle capable of accommodating the new musical identities resulting from their socially diverse and diasporic realities. -

February 1931

Ir• february 1931 Je~nelle Vol. 2 . No.4. M'Donold WAVE-LENGTH GUIDE .,. d NATIOIIAL a: WHAT'S ON THE AIR COLUMBIA .,. z ... .... BIAl RWIN8 ! 8ROABCASTIN8 8ROABCASTIN8 <.:> t:; (Registered in U . S. Patent Office) .. SYSTtl( COMpm t: =- 1 WKRO WGR-ltSD 660 645 .- Vol. II. MAGAZINE FOR THE RADIO USTENER No.4 2 KLZ·WQAM WFI-WmO 660 636 .- ffi 670 626 =r- 3 WWNC-WKBN .- r- J;'UBLISHED MONTHLY AT NINTH AND CUTTER STS., CINOINNATI, 0., 4 WIBW-WNAX WTAG 680 617 .- r----- BY WHAT'S ON THE AIR CO. PRINTED IN U. S. A. 6 WMT WOW-WEEI 690 608 I-- .- r- EDITORIAL AND OIROULATION OFI'IOES: Box 6, STATION N, CINOIN 6 WCAO-WREC 600 600 .- NATI, O. 7 WDAF 610 492 f---- WFAN .- ADVERTISING OFJ'IOES: 11 W. FORTY-SEOOND ST., NEW YORK CITY. 8 WLBZ WTMJ-WFLA 620 484 .- r- PRIOE, 150. PER OOPY; $1.50 PER YEAR . 9 WMAL 630 476 .- I--- 10 WAIU 640 468 .- m (COPYRIGHT, 1930, BY WHAT' ~ ON THE Am CO.) - 11 WSM 660 461 .- - PATENTS APPLIED I'OR OOVER BASIO J'EATURES 01' PROGRAM-I'INDING 12 WEAF 660 464 .- - SERVIOE OI'FERED IN THIS MAGAZINE. 670 447 13 WMAQ .- "ENTERED AS SEOOND-OLASS MATTER APR. 19, 1930, AT THE POST 14 WPTF-CKGW 680 441 .- OI'I'IOE AT CINOINNATI, 0., UNDER THE AOT 01' M.A&oH 3, 1879." 16 WLW 700 428 .- 17 710 422 .- m~ 18 CKAC WGN 720 416 .- r- f--- 20 WSB 740 406 .- r- HOW TO FIND THE The program-finding service covers the 21 760 400 hours of 6 to 12 P. -

Christine Walevska

Dépliant 4 pages / 4 page Folder Design #21002 Christine Walevska Artist bio will be going here. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetuer adipiscing elit. Aenean commodo ligula eget dolor. Aenean massa. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Donec quam felis, ultricies nec, pellentesque eu, pretium quis, sem. Nulla consequat massa quis enim. Donec pede justo, fringilla vel, aliquet nec, vulputate eget, arcu. In enim justo, rhoncus ut, imperdiet a, venenatis vitae, justo. Nullam dictum felis eu pede mollis pretium. Integer tincidunt. Cras dapibus. Vivamus elementum semper nisi. Aenean vulputate eleifend tellus. Aenean leo ligula, porttitor eu, consequat vitae, eleifend ac, enim. Aliquam lorem ante, dapibus in, viverra quis, feugiat a, tellus. Phasellus viverra nulla ut metus varius laoreet. Quisque Christine rutrum. Aenean imperdiet. Etiam ultricies nisi vel augue. Curabitur ullamcorper ultricies nisi. Nam eget dui. Etiam rhoncus. Maecenas tempus, tellus eget condimentum rhoncus, sem quam semper libero, sit amet adipiscing sem neque sed ipsum. Nam quam nunc, blandit vel, luctus pulvinar, hendrerit id, lorem. Maecenas nec odio et ante tincidunt tempus. Donec vitae sapien ut libero Walevska venenatis faucibus. Nullam quis ante. Etiam sit amet orci eget eros faucibus tincidunt. Duis leo. Sed fringilla mauris sit amet nibh. Donec sodales sagittis magna. Sed consequat, leo eget bibendum sodales, augue velit cursus nunc, quis gravida magna mi a libero. Fusce vulputate eleifend sapien. Vestibulum purus quam, scelerisque ut, mollis sed, nonummy id, metus. Nullam accumsan lorem in dui. Cras ultricies mi eu turpis hendrerit fringilla. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; In ac dui quis mi Goddess of Album Credits the Cello Christine Walevska, Cello Akimi Fukuhara, Piano Recording Producer - Martha De Francisco Recording Engineer - Padraig Buttner-Schnirer Recorded at Pollack Concert Hall, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, June 2014. -

CI ILUA 11)Ljl1kiero (I) I-T Iast` I S (.1

TA__A,_ IL) I Co II' 1=1_ Co S CI ILUA 11)LJL1kIEro (I) I-t iAST` I S (.1 9 :30-Walter Winchell molmic-Symphony Oreh., 7:00-Court of Human EelS-6 :30-Genealogy-K. Minot 9 :45-Gould and Shefter, Hans Lange, Conductor; tions-Sketch Pitma,n Piano Duo Poldi Mlldner, Piano 7:45-Wendell Hall, Songs 6:45-Red Lacguer and Jade 5:00-Roses and Drums; SUNDAY, JAN. 14 TODAY, JAN. 7 8:00-Eddie Cantor. Come- 7 :15-News-Gabriel Heatter10 :00-Tiger Ghost-Sketch 1 ductor; Roth String Quartet; Joseph dim ; Rubinoff Orch. 7:30-Johnston Orcil. ; Veron-10 :30-Carlos Gardel. Bert- Road Around Richmond- Szigeti, Violin-WOR. 9:00-Rodemich Orcb. ;Da- ica Wiggins, Contralto; tone; Macian-i Orch. Sketch LEADING EVENTS 3:30-4:00-From London:"Whither Brit- vid Percy,Songs; Male Fred Vettel, Tenor 11 :00-Master Singers 5 :30-Frank Cmumlt and WEAF-660 ho WJZ-'760 Xc Eastern Standard Time Is Used in All Cases; Trio; Tamara, Songs S :00-Vera Brodsky and 11 :15-Ennio Bolognini. Cello Julia Sanderson, Songs 10 :00 A. 51,-The Inward 10 :30 A. M.-Samovar Sere- am?" H. G. Wells, Author-WABC, Stations Arranged in Accordance Frank Harold Trigga, Piano Duo11 :30-Vallee Oreh. 6:00-Muriel Wilson, So- Change-Dr. S. Parkes nade WEAF. 9 :30-Concert Orcb. ; 8:15-Rita Gould, Songs 12 :00-LuncefOrd Orcb. prano;Oliver Smith, (Jan. 7-13.) 9 :30-10 :30-Providence Symphony Orchestra With Dial Locations- Munn, Tenor;Virginia 1.2 :30 A. -

Violin Periphery: Nuevo Tango in Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études and Minimalism in Philip Glass' Sonata for Violin and Piano Jenny Lee Vaughn

Florida State University Libraries 2016 Violin Periphery: Nuevo Tango in Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études and Minimalism in Philip Glass' Sonata for Violin and Piano Jenny Lee Vaughn Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC VIOLIN PERIPHERY: NUEVO TANGO IN ASTOR PIAZZOLLA’S TANGO-ÉTUDES AND MINIMALISM IN PHILIP GLASS’ SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO By JENNY LEE VAUGHN A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music 2016 © 2016 Jenny Lee Vaughn Jenny Lee Vaughn defended this treatise on April 12, 2016. The members of the supervisory committee were: Benjamin Sung Professor Directing Treatise James Mathes University Representative Pamela Ryan Committee Member Corinne Stillwell Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the treatise has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii To Dr. Mary Lee Cochran, who nurtured me in so many ways and introduced me to the music of Astor Piazzolla. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I extend thanks to my major professor, Dr. Benjamin Sung. He made my doctoral work exceedingly enjoyable and fulfilling, and continues to provide a fine example of how to approach challenges with logic and a cool head. I also appreciate the valuable input provided by my committee for this treatise. Additionally, I have known Dr. Mathes and Dr. Ryan for over fifteen years, and happily recognize their individual roles in shaping my undergraduate experience many years ago. -

Image to PDF Conversion Tools

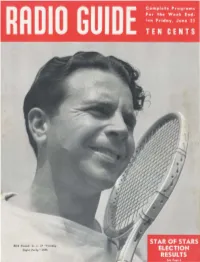

, Dicit: Powell, m. c. of "Tuesday Night Party," CBS , . I,U P • RADIO GUIDE • A weekl y pe riodical of program s, pictures a nd personalities • Nelson Eddy IS El ected Star of Stars by Listeners IN WHAT is probably Paderewsld's De bt: The tour recently made by Marie Dressler Cot the greatest national Ignace Paderewski was marred by illness. At the last, tage: The benefits from poll of radio favorites a heart attack forced him radio are sometimes un· ever conducted, the radio to cancel what was to expected. Who. for in· listeners 01 America have have been a triumphant stance, would have just elected Nelson Eddy farewen performance in thought that the idea as their Star of Stars, New York. Nevertheless, born in the minds of two making him the most he is reported to have Hollywood humanitarians popular entertainer on made enough money to some years ago would the air during the radio keep him in comfort to have given both good season of 1938-1939. In the end of his life. Before entertainment to a nation II surprisingly dose fin- he came to America this of radio listeners as well Edgar Bergen ish, Jessica Dragonette last time, he was penni· as 5220.000 in cash to Marie Dressler look second place, Edgar less. Worse, he was told needy folk in the screen Bergen took third, and Jack Benny placed fourth. that he owed the United capital? On June 4. the Screen Actors Guild show We congratulate them all on their splendid talents States goverOlment about completed its 1939 season. -

Acercamiento a La Interpretación Del Tango En El Violín

Acercamiento a la interpretación del tango en el violín Propuesta de ejecución interpretativa en el violín de tres de los Six Tango-Etudes pour flûte seule de Astor Piazzolla Autor: Sebastián Montoya Vallejo1 [email protected] Resumen Una vez observada la fuerza que ha tenido el tango en la escena musical local y nacional, y a pesar de que dicho género ha sido declarado como patrimonio de la humanidad por la UNESCO, su genuina y mejor interpretación no se encuentra relacionada con exactitud en las partituras originales de sus obras más representativas, toda vez que sus compositores tuvieron una preocupación menor por plasmar en la partitura las herramientas interpretativas típicas, y que eligieron hacer mayor énfasis en la ejecución de las técnicas tangueras concomitante con la interpretación del instrumento. Razón por la cual en el texto se pretende elaborar una propuesta interpretativa del violín en el tango a partir de tres de los Six Tango-Etudes pour flûte seule de Astor Piazzolla mediante el análisis de grabaciones de Astor Piazzola y de los trabajos investigativos realizados por Ramiro Gallo. La propuesta interpretativa realizada en este trabajo permite a violinistas con formación académica acercarse a la interpretación del tango con la técnica tradicional no sin antes advertir que existirán numerosas maneras de tocar tango, como bien lo dice Gallo, por lo que es necesario complementar con observación de grabaciones de otros referentes del tango Palabras clave: Tango, violín, interpretación, Estudios, Tangueros, Piazzolla, Tanguísticos Abstract Strength of the tango in the local and national music scene has been observed. Despite the fact that this genre has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, its genuine and better interpretation is not related with accuracy in the originals scores of their most representative works, maybe, because the composers had a minor concern to capture the interpretive tools in the score, but they chose to place greater emphasis on the execution of tango techniques in the interpretation of the instrument. -

A Performer's Guide to Astor Piazzolla's <I>Tango-Études Pour Flûte Seule</I>: an Analytical Approach

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2018 A Performer’s Guide to Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études pour flûte seule: An Analytical Approach Asis Reyes The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2509 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO ASTOR PIAZZOLLA'S TANGO-ÉTUDES POUR FLÛTE SEULE: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH by ASIS A. REYES A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 ASIS REYES All Rights Reserved ii A Performer’s Guide to Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études pour flûte seule: An Analytical Approach by Asis A. Reyes This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Date Professor Peter Manuel Chair of Examining Committee Date Professor Norman Carey Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Antoni Pizà, Advisor Thomas McKinley, First Reader Tania Leon, Reader THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT A Performer’s Guide to Astor Piazzolla's Tango-Études pour flûte seule: An Analytical Approach by Asis A. Reyes Advisor: Antoni Pizà Abstract/Description This dissertation aims to give performers deeper insight into the style of the Tango- Études pour flûte seule and tango music in general as they seek to learn and apply tango performance conventions to the Tango-Études and other tango works.