Images of Roman Imperial Denarii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

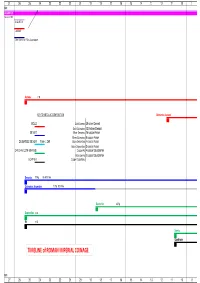

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

Diadumenian from Seleuceia Ad Calycadnum

Coins bearing the image of Diadumenian from Seleuceia ad Calycadnum This ancient city called Seleuceia (by which the modern town of Silifke now stands) was founded in the 3 rd Century BC by Seleucus I (Nicator), known commonly as Seleuceia ad Calycadnum as it is sited close to the river Calycadnus (now the Göksu ). After successfully campaigning as one of Alexander’s generals, Seleucus Nicator named cities after himself and his wife, Apama (e.g. Apameia in Phygria). This particular city produced Roman provincial coinage from the reigns of Hadrian through to that of Gallenius, with the pronounced exception of Elagabalus. Excavations at the city have revealed that the only surviving, identifiable temple from the time seems to have been dedicated to Zeus – dating from 2 nd -3rd century AD, locally known as the temple of the storks due to the colony established there. Figure 1 Figure 2 (Images courtesy of http://www.anatolia.luwo.be ) Figures 1 and 2 show the remains of the Temple of Zeus that can be found today. While examples showing Macrinus also exist there appears to have been two denominations issued specifically for Diadumenian at this mint – during the year or so that Macrinus was in power. One, at 20-21mm and 4-6g and a larger type 28mm and around 11.5g, each with two distinct reverse types associated with them. Example 1 Οb, M O Π ∆ΙΑ∆Ο V ANT ΩN K Rev . CΕΛΕ VKE ΩN Ref. Lindgren 1583 (illustrated with permission); 21mm, 6.1g, Example 1 shows a reverse of Athena and Dionysus. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg's Corpora Of

This is a repository copy of Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/124522/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Jarrett, J orcid.org/0000-0002-0433-5233 (2018) Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata. Numismatic Chronicle, 177. pp. 514-535. ISSN 0078-2696 © 2017 The Author. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Numismatic Chronicle. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ REVIEW ARTICLE Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg’s Corpora of Nomismata* JONATHAN JARRETT FRANZ FÜEG, Corpus of the Nomismata from Anastasius II to John I in Constantinople 713–976: Structure of the Issues; Corpus of Coin Finds; Contribution to the Iconographic and Monetary History, trans. -

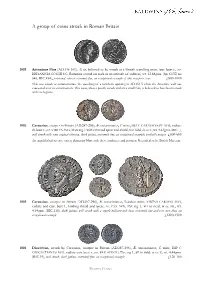

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Deities from Egypt on Coins of Southern Levant Laurent Bricault

Deities from Egypt on Coins of Southern Levant Laurent Bricault To cite this version: Laurent Bricault. Deities from Egypt on Coins of Southern Levant. Israel Numismatic Research, 2006, 1, p. 123-135. hal-00567311 HAL Id: hal-00567311 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00567311 Submitted on 20 Feb 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Israel Numismatic Research Published by the Israel Numismatic Society Volume 1 2006 Contents 3 Upon the Appearance of the First Issue of Israel Numismatic Research 5HAIM GITLER:AHacksilber and Cut Athenian Tetradrachm Hoard from the Environs of Samaria: Late Fourth Century BCE 15 CATHARINE C. LORBER: The Last Ptolemaic Bronze Emission of Tyre 21 DANNY SYON: Numismatic Evidence of Jewish Presence in Galilee before the Hasmonean Annexation? 25 OLIVER D. HOOVER: A Late Hellenistic Lead Coinage from Gaza 37 ANNE DESTROOPER: Jewish Coins Found in Cyprus 51 DANIEL HERMAN: The Coins of the Itureans 73 JEAN-PHILIPPE FONTANILLE and DONALD T. ARIEL: The Large Dated Coin of Herod the Great: The First Die Series 87 DAVID M. HOFFEDITZ: Divus of Augustus: The Influence of the Trials of Maiestas upon Pontius Pilate’s Coins 97 STEPHEN N. -

A Handbook of Greek and Roman Coins

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1891 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library CJ 237.H64 A handbook of Greek and Roman coins. 3 1924 021 438 399 Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021438399 f^antilioofcs of glrcfjaeologj) anU Antiquities A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS A HANDBOOK OF GREEK AND ROMAN COINS G. F. HILL, M.A. OF THE DEPARTMENT OF COINS AND MEDALS IN' THE bRITISH MUSEUM WITH FIFTEEN COLLOTYPE PLATES Hon&on MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY l8 99 \_All rights reserved'] ©jcforb HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY PREFACE The attempt has often been made to condense into a small volume all that is necessary for a beginner in numismatics or a young collector of coins. But success has been less frequent, because the knowledge of coins is essentially a knowledge of details, and small treatises are apt to be un- readable when they contain too many references to particular coins, and unprofltably vague when such references are avoided. I cannot hope that I have passed safely between these two dangers ; indeed, my desire has been to avoid the second at all risk of encountering the former. At the same time it may be said that this book is not meant for the collector who desires only to identify the coins which he happens to possess, while caring little for the wider problems of history, art, mythology, and religion, to which coins sometimes furnish the only key. -

![The Holy Roman Empire [1873]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7391/the-holy-roman-empire-1873-1457391.webp)

The Holy Roman Empire [1873]

The Online Library of Liberty A Project Of Liberty Fund, Inc. Viscount James Bryce, The Holy Roman Empire [1873] The Online Library Of Liberty This E-Book (PDF format) is published by Liberty Fund, Inc., a private, non-profit, educational foundation established in 1960 to encourage study of the ideal of a society of free and responsible individuals. 2010 was the 50th anniversary year of the founding of Liberty Fund. It is part of the Online Library of Liberty web site http://oll.libertyfund.org, which was established in 2004 in order to further the educational goals of Liberty Fund, Inc. To find out more about the author or title, to use the site's powerful search engine, to see other titles in other formats (HTML, facsimile PDF), or to make use of the hundreds of essays, educational aids, and study guides, please visit the OLL web site. This title is also part of the Portable Library of Liberty DVD which contains over 1,000 books and quotes about liberty and power, and is available free of charge upon request. The cuneiform inscription that appears in the logo and serves as a design element in all Liberty Fund books and web sites is the earliest-known written appearance of the word “freedom” (amagi), or “liberty.” It is taken from a clay document written about 2300 B.C. in the Sumerian city-state of Lagash, in present day Iraq. To find out more about Liberty Fund, Inc., or the Online Library of Liberty Project, please contact the Director at [email protected]. -

Stellar Symbols on Ancient Coins of the Roman Empire – Part Iii: 193–235 Ad

STELLAR SYMBOLS ON ANCIENT COINS OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE – PART III: 193–235 AD ELENI ROVITHIS-LIVANIOU1, FLORA ROVITHIS2 1Dept of Astrophysics, Astronomy & Mechanics, Faculty of Physics, Athens University, Panepistimiopolis, Zographos 15784, Athens, Greece Email: [email protected] 2Email: fl[email protected] Abstract. We continue to present and describe some ancient Roman coins with astro- nomical symbols like the Moon, the Zodiac signs, the stars, etc. The coins presented in this Paper correspond to the Roman Empire covering the interval (193 - 235) AD, which corresponds mainly to the Severan dynasty. Key words: Astronomy in culture – Ancient Roman coins – Roman emperors – Stellar symbols. 1. PROLOGUE In a series of papers ancient Greek and Roman coins with astronomical sym- bols were shown, (Rovithis-Livaniou and Rovithis, 2011–2012 and 2014–2015,a&b). Especially the last two of them, hereafter referred as Paper I & II corresponded to the Roman Empire and covered the intervals 27 BD to 95 AD and 96 to 192 AD, re- spectively. Thus, the Roman numismatic system, and its coins has been examined in detail. For this reason, we do not repeat it here, where we continue with coins of the same subject covering the period (193–235) AD that corresponds mainly to the Severan dynasty. What it is worthwhile to be mentioned is that during this time interval, and when there was some numismatic crisis, the silver contain of the denary was reduced. For example during Caracalla’s[1] epoch a specific silver plated coin with less silver than denary was issued the so-called antonianus or the radiative. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship. WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA How to cite: WILLIAMS-REED, ERIS,KATHLYN,LAURA (2018) Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/13052/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Water and Religious Life in the Roman Near East. Gods, Spaces and Patterns of Worship Eris Kathlyn Laura Williams-Reed A thesis submitted for the qualification of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History Durham University 2018 Acknowledgments It is a joy to recall the many people who, each in their own way, made this thesis possible. Firstly, I owe a great deal of thanks to my supervisor, Ted Kaizer, for his support and encouragement throughout my doctorate, as well as my undergraduate and postgraduate studies. -

Byzantine Coinage

BYZANTINE COINAGE Philip Grierson Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. © 1999 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Second Edition Cover illustrations: Solidus of Justinian II (enlarged 5:1) ISBN 0-88402-274-9 Preface his publication essentially consists of two parts. The first part is a second Tedition of Byzantine Coinage, originally published in 1982 as number 4 in the series Dumbarton Oaks Byzantine Collection Publications. Although the format has been slightly changed, the content is fundamentally the same. The numbering of the illustrations,* however, is sometimes different, and the text has been revised and expanded, largely on the advice and with the help of Cécile Morrisson, who has succeeded me at Dumbarton Oaks as advisor for Byzantine numismatics. Additions complementing this section are tables of val- ues at different periods in the empire’s history, a list of Byzantine emperors, and a glossary. The second part of the publication reproduces, in an updated and slightly shorter form, a note contributed in 1993 to the International Numismatic Commission as one of a series of articles in the commission’s Compte-rendus sketching the histories of the great coin cabinets of the world. Its appearance in such a series explains why it is written in the third person and not in the first. It is a condensation of a much longer unpublished typescript, produced for the Coin Room at Dumbarton Oaks, describing the formation of the collection and its publication. * The coins illustrated are in the Dumbarton Oaks and Whittemore collections and are re- produced actual size unless otherwise indicated.