Middle Byzantine Numismatics in the Light of Franz Füeg's Corpora Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

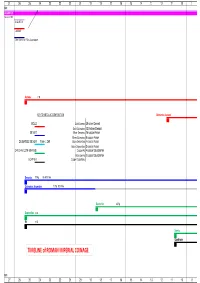

TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE

27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 B.C. AUGUSTUS 16 Jan 27 BC AUGUSTUS CAESAR Other title: e.g. Filius Augustorum Aureus 7.8g KEY TO METALLIC COMPOSITION Quinarius Aureus GOLD Gold Aureus 25 silver Denarii Gold Quinarius 12.5 silver Denarii SILVER Silver Denarius 16 copper Asses Silver Quinarius 8 copper Asses DE-BASED SILVER from c. 260 Brass Sestertius 4 copper Asses Brass Dupondius 2 copper Asses ORICHALCUM (BRASS) Copper As 4 copper Quadrantes Brass Semis 2 copper Quadrantes COPPER Copper Quadrans Denarius 3.79g 96-98% fine Quinarius Argenteus 1.73g 92% fine Sestertius 25.5g Dupondius 12.5g As 10.5g Semis Quadrans TIMELINE of ROMAN IMPERIAL COINAGE B.C. 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 A.D.A.D. denominational relationships relationships based on Aureus Aureus 7.8g 1 Quinarius Aureus 3.89g 2 Denarius 3.79g 25 50 Sestertius 25.4g 100 Dupondius 12.4g 200 As 10.5g 400 Semis 4.59g 800 Quadrans 3.61g 1600 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 19 Aug TIBERIUS TIBERIUS Aureus 7.75g Aureus Quinarius Aureus 3.87g Quinarius Aureus Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine Denarius Sestertius 27g Sestertius Dupondius 14.5g Dupondius As 10.9g As Semis Quadrans 3.61g Quadrans 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 TIBERIUS CALIGULA CLAUDIUS Aureus 7.75g 7.63g Quinarius Aureus 3.87g 3.85g Denarius 3.76g 96-98% fine 3.75g 98% fine Sestertius 27g 28.7g -

SINCONA Auction 17 312.Pdf

Antike Münzen & Siegel Auktion 17 21. Mai 2014 Zürich Hotel Savoy-Baur en Ville Poststrasse 12 CH-8001 Zürich Unter Aufsicht des Stadtammannamtes Zürich SINCONA AG Uraniastrasse 11 CH-8001 Zürich Tel. +41-44-215 10 90 Fax +41-44-215 10 99 © 2014 SINCONA AG, Zürich –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– Auktionsbedingungen Für die SINCONA Auktion 17 gelten folgende Versteigerungsbedingun- Für staatlich geprägte Goldmünzen und das darauf anfallende Auf- gen, welche durch die Abgabe eines schriftlichen, elektronischen, münd- geld wird keine Mehrwertsteuer erhoben. lichen oder telefonischen Gebotes vollumfänglich anerkannt werden: Die Mehrwertsteuer entfällt, sofern die Auktionslose durch den Ver- 1. Die Versteigerung erfolgt freiwillig und öffentlich im Namen der steigerer ins Ausland spediert werden. Käufern mit Wohnsitz aus- SINCONA AG für Rechnung des oder der ungenannt bleibenden serhalb der Schweiz, welchen die ersteigerten Auktionslose in Zürich Einlieferer. ausgehändigt werden, wird die Mehrwertsteuer vorerst in Rechnung gestellt, jedoch nach Vorliegen der definitiven Veranlagungsverfü- 2. Der SINCONA AG (im Folgenden "Versteigerer" genannt) unbe- gung des Schweizer Zolls vom Versteigerer vollumfänglich zurück- kannte Bieter sind gebeten, sich vor der Auktion zu legitimieren. erstattet. Ferner behält sich der Versteigerer vor, nach freiem Ermessen und ohne Angabe von Gründen Personen den Zutritt zu den Auktions- 8. Die Auktionsrechnung ist sofort nach Erhalt, spätestens aber innert räumlichkeiten zu untersagen. 10 Tagen nach Auktionsende zu bezahlen. Nach Ablauf der Zah- lungsfrist fällt der Käufer automatisch in Zahlungsverzug und der Der Versteigerer ist mit Zustimmung der Auktionsaufsicht berech- Versteigerer ist berechtigt, Zinsen in der Höhe von 10% p.a. zu ver- tigt, von der im Katalog vorgesehenen Reihenfolge abzuweichen und langen. Bei Zahlungsverzug des Käufers oder bei Verweigerung der Nummern zu vereinigen. -

How to Collect Coins a Fun, Useful, and Educational Guide to the Hobby

$4.95 Valuable Tips & Information! LITTLETON’S HOW TO CCOLLECTOLLECT CCOINSOINS ✓ Find the answers to the top 8 questions about coins! ✓ Are there any U.S. coin types you’ve never heard of? ✓ Learn about grading coins! ✓ Expand your coin collecting knowledge! ✓ Keep your coins in the best condition! ✓ Learn all about the different U.S. Mints and mint marks! WELCOME… Dear Collector, Coins reflect the culture and the times in which they were produced, and U.S. coins tell the story of America in a way that no other artifact can. Why? Because they have been used since the nation’s beginnings. Pathfinders and trendsetters – Benjamin Franklin, Robert E. Lee, Teddy Roosevelt, Marilyn Monroe – you, your parents and grandparents have all used coins. When you hold one in your hand, you’re holding a tangible link to the past. David M. Sundman, You can travel back to colonial America LCC President with a large cent, the Civil War with a two-cent piece, or to the beginning of America’s involvement in WWI with a Mercury dime. Every U.S. coin is an enduring legacy from our nation’s past! Have a plan for your collection When many collectors begin, they may want to collect everything, because all different coin types fascinate them. But, after gaining more knowledge and experience, they usually find that it’s good to have a plan and a focus for what they want to collect. Although there are various ways (pages 8 & 9 list a few), building a complete date and mint mark collection (such as Lincoln cents) is considered by many to be the ultimate achievement. -

The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1

Year 4: The Roman Empire – Roman Coins Lesson 1 Duration 2 hours. Date: Planned by Katrina Gray for Two Temple Place, 2014 Main teaching Activities - Differentiation Plenary LO: To investigate who the Romans were and why they came Activities: Mixed Ability Groups. AFL: Who were the Romans? to Britain Cross curricular links: Geography, Numeracy, History Activity 1: AFL: Why did the Romans want to come to Britain? CT to introduce the topic of the Romans and elicit children’s prior Sort timeline flashcards into chronological order CT to refer back to the idea that one of the main reasons for knowledge: invasion was connected to wealth and money. Explain that Q Who were the Romans? After completion, discuss the events as a whole class to ensure over the next few lessons we shall be focusing on Roman Q What do you know about them already? that the children understand the vocabulary and events described money / coins. Q Where do they originate from? * Option to use CT to show children a map, children to locate Rome and Britain. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm or RESOURCES Explain that the Romans invaded Britain. http://resources.woodlands-junior.kent.sch.uk/homework/romans.html Q What does the word ‘invade’ mean? for further information about the key dates and events involved in Websites: the Roman invasion. http://www.schoolsliaison.org.uk/kids/preload.htm To understand why they invaded Britain we must examine what http://www.sparklebox.co.uk/topic/past/roman-empire.html was happening in Britain before the invasion. -

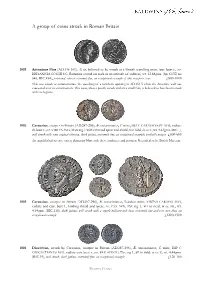

A Group of Coins Struck in Roman Britain

A group of coins struck in Roman Britain 1001 Antoninus Pius (AD.138-161), Æ as, believed to be struck at a British travelling mint, laur. bust r., rev. BRITANNIA COS III S C, Britannia seated on rock in an attitude of sadness, wt. 12.68gms. (Sp. COE no 646; RIC.934), patinated, almost extremely fine, an exceptional example of this very poor issue £800-1000 This was struck to commemorate the quashing of a northern uprising in AD.154-5 when the Antonine wall was evacuated after its construction. This issue, always poorly struck and on a small flan, is believed to have been struck with the legions. 1002 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C CARAVSIVS PF AVG, radiate dr. bust r., rev. VIRTVS AVG, Mars stg. l. with reversed spear and shield, S in field,in ex. C, wt. 4.63gms. (RIC.-), well struck with some original silvering, dark patina, extremely fine, an exceptional example, probably unique £600-800 An unpublished reverse variety depicting Mars with these attributes and position. Recorded at the British Museum. 1003 Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, London mint, VIRTVS CARAVSI AVG, radiate and cuir. bust l., holding shield and spear, rev. PAX AVG, Pax stg. l., FO in field, in ex. ML, wt. 4.14gms. (RIC.116), dark patina, well struck with a superb military-style bust, extremely fine and very rare thus, an exceptional example £1200-1500 1004 Diocletian, struck by Carausius, usurper in Britain (AD.287-296), Æ antoninianus, C mint, IMP C DIOCLETIANVS AVG, radiate cuir. -

Reno Cartwheel February 2021

Page 1 Reno Cartwheel February 2021 Next Meeting: 2020 NA &CT, MA, MD, SC Innovation $1, Bush $1 and 2019S .25 sets here. Tuskegee .25 ordered. MARCH MAYBE??!! F ebruary 19-21, Reno Coin Show, Silver Legacy , Admit: $3, $1 with registration, 10-6 Friday and Saturday, 10-4 on Sunday.(COVID-19 restrictions: first hour maximum of 50 people in the room). Additional hours are $1 when the show is at maximum capacity. PCGS submissions will be accepted. John Ward 559 967-8067 Info www. coinzip.com/Reno-Coin-Show-Silver-Legacy February 23 6:30PM Board Meeting only Dennys, 205, Nugett Ave, Sparks After the Last Cancelled Meeting Reno Coin Show and Board meeting this month. Ordered Tuskegee airmen coin, last S set of all five 2013-2019 quarters in case $5 American the Beautiful .25. Got Kansas butterfly National Park Quarters PDS .50 .25, Bush $1, Hubble $1, and last 2020 Innovation, Native American $1 D P $1.25 Innovation dollar. Call and come by to get any of the new coins if you want. John Ward’s coin New Coins show on, at Silver Legacy February 19-21 Info: The Trump presidential medal with price tripled at 1.5 559 967-8067. Details at CoinZip.com We get a inches for $20 and quadrupled at 3 inch at $160 is back table and will do a raffle. Need help on Friday ordered. I have found a six quarter case to put the S sets 19th. ANA Coin Week April 18-24 Money, Big together for the 2020 and 2021 quarters. -

The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark

The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark Danmarks Nationalbank's building in Copenhagen was designed by the internationally renowned Danish architect Arne Jacobsen and built between 1965-1978 The Coins and Banknotes of Denmark, 2nd edition, August 2005 Text may be copied from this publication provided that This edition closed for contributions in July 2005. Danmarks Nationalbank is specifically stated as the sour- Print: Fr. G. Knudtzon's Bogtrykkeri A/S ce. Changes to or misrepresentation of the content are ISBN 87-87251-55-8 not permitted. For further information about coins and (Online) ISBN 87-87251-56-6 banknotes, please contact: Danmarks Nationalbank, Information Desk Havnegade 5 DK-1093 Copenhagen K Telephone +45 33 63 70 00 (direct) or +45 33 63 63 63 E-mail [email protected] www.nationalbanken.dk 2 Old and new traditions s the central bank of Denmark, Danmarks There are many traditions linked to the appearan- ANationalbank has the sole right to produce ce of banknotes and coins, but the designs are also and issue Danish banknotes and coins. Subject to subject to ongoing renewal and development. For the approval of the Minister for Economic and Bus- instance, the Danish banknote series has been iness Affairs, Danmarks Nationalbank determines upgraded with new security features – holograms the appearance of Danish banknotes and coins and fluorescent colours. The coin series has been and their denominations. supplemented with a tower series and a fairy tale This brochure provides a brief description – in text series, the latter also in silver and gold editions. As and pictures – of the process from the artist's first a consequence of these changes, the time has sketch until the banknotes and coins are put into come to update this publication. -

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi

The Byzantine State and the Dynatoi A struggle for supremacy 867 - 1071 J.J.P. Vrijaldenhoven S0921084 Van Speijkstraat 76-II 2518 GE ’s Gravenhage Tel.: 0628204223 E-mail: [email protected] Master Thesis Europe 1000 - 1800 Prof. Dr. P. Stephenson and Prof. Dr. P.C.M. Hoppenbrouwers History University of Leiden 30-07-2014 CONTENTS GLOSSARY 2 INTRODUCTION 6 CHAPTER 1 THE FIRST STRUGGLE OF THE DYNATOI AND THE STATE 867 – 959 16 STATE 18 Novel (A) of Leo VI 894 – 912 18 Novels (B and C) of Romanos I Lekapenos 922/928 and 934 19 Novels (D, E and G) of Constantine VII Porphyrogenetos 947 - 959 22 CHURCH 24 ARISTOCRACY 27 CONCLUSION 30 CHAPTER 2 LAND OWNERSHIP IN THE PERIOD OF THE WARRIOR EMPERORS 959 - 1025 32 STATE 34 Novel (F) of Romanos II 959 – 963. 34 Novels (H, J, K, L and M) of Nikephoros II Phokas 963 – 969. 34 Novels (N and O) of Basil II 988 – 996 37 CHURCH 42 ARISTOCRACY 45 CONCLUSION 49 CHAPTER 3 THE CHANGING STATE AND THE DYNATOI 1025 – 1071 51 STATE 53 CHURCH 60 ARISTOCRACY 64 Land register of Thebes 65 CONCLUSION 68 CONCLUSION 70 APPENDIX I BYZANTINE EMPERORS 867 - 1081 76 APPENDIX II MAPS 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY 82 1 Glossary Aerikon A judicial fine later changed into a cash payment. Allelengyon Collective responsibility of a tax unit to pay each other’s taxes. Anagraphis / Anagrapheus Fiscal official, or imperial tax assessor, who held a role similar as the epoptes. Their major function was the revision of the tax cadastre. It is implied that they measured land and on imperial order could confiscate lands. -

Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul Area Snelders, B

Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area Snelders, B. Citation Snelders, B. (2010, September 1). Identity and Christian-Muslim interaction : medieval art of the Syrian Orthodox from the Mosul area. Peeters, Leuven. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15917 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/15917 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). 2. The Syrian Orthodox in their Historical and Artistic Settings 2.1 Northern Mesopotamia and Mosul The blossoming of ‘Syrian Orthodox art’ during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries is mainly attested for Northern Mesopotamia. At the time, Northern Mesopotamia was commonly known as the Jazira (Arabic for ‘island’), a geographic entity encompassing roughly the territory which is located between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, and lies north of Baghdad and south of Lake Van. 1 In ecclesiastical terms, this region is called Athur (Assyria). 2 Early Islamic historians and geographers distinguished three different districts: Diyar Mudar, Diyar Bakr, and Diyar Rabi cah. Today, these districts correspond more or less to eastern Syria, south-eastern Turkey, and northern Iraq, respectively. Mosul was the capital of the Diyar Rabi cah district, which ‘extended north from Takrit along both banks of the Tigris to the tributary Ba caynatha river a few kilometres north of Jazirat ibn cUmar (modern Cizre) and westwards along the southern slopes of the Tur cAbdin as far as the western limits of the Khabur Basin’. -

50 State Quarters Lesson Plans, Grades 9 Through 12

5: A World of Money Modern World History CLASS TIME Four 45- to 50-minute sessions OBJECTIVES Students will identify, recognize, and appreciate continuing global traditions related to the creation of national currencies. They will evaluate and analyze the role currency plays in shaping a national or regional identity. They will discuss and predict how regional, cultural, and national identity influences the designers of world currency. NATIONAL STANDARDS The standards used for these lesson plans reference the “10 Thematic Standards in Social Studies” developed by the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). • Culture—Students should be able to demonstrate the value of cultural diversity, as well as cohesion, within and across groups. Students should be able to construct reasoned judgments about specific cultural responses to persistent human issues. • Time, Continuity, and Change—Students should be able to investigate, interpret, and analyze multiple historical and contemporary viewpoints within and across cultures related to important events, recurring dilemmas, and persistent issues, while employing empathy, skepticism, and critical judgment. • Individual Development and Identity—Students should be able to articulate personal connections to time, place, and social and cultural systems. • Individuals, Groups, and Institutions—Students should be able to analyze group and institutional influences on people, events, and elements of culture in both historical and contemporary settings. TERMS AND CONCEPTS: • The United States Mint 50 State Quarters® Program • Medium of exchange • Legal tender • Commemorative • Motto • Emblem • Symbolism • Nationalism • Patriotism • Circulating coin • Obverse (front) • Reverse (back) • Bust • Designer PORTIONS © 2004 U.S. MINT. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. 30 Grades 9 through 12 A World of Money SESSION 1 Materials • Chalkboard or whiteboard • Chalk or markers • Chart paper • Packets of U.S. -

Dumbarton Oaks Papers, No. 55

This is an extract from: Dumbarton Oaks Papers, No. 55 Editor: Alice-Mary Talbot Published by Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection Washington, D.C. Issue year 2001 © 2002 Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University Washington, D.C. Printed in the United States of America www.doaks.org/etexts.html The Normans between Byzantium and the Islamic World LUCIA TRAVAINI hendealing with the subject of monetary transactions and exchanges involving the WNormans of Italy, Byzantium, and the Islamic world, scholars have been cautioned to use care when discussing terms such as influence (was there a donor culture?), borrowing (was it residual, recent, or antiquarian?), and propaganda which certainly played a role in Norman thinking and practice.1 What do we mean by “the Normans in Italy”? There were at least three or four Norman Italies: Byzantine, Lombard, Muslim, and French- Norman, each having its own monetary tradition, different from each other and well documented in charters and finds. The many frontiers of medieval Italy are particularly mobile and certainly existed in the period under examination, the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 Ce´cile Morrisson read a first draft of this paper; Vera von Falkenhausen and Jonathan Shepard helped me with precious references; Philip Grierson revised my English in the final version. I am very grateful to all of them for comments and discussion. 1M. McCormick, “Byzantium and the Early Medieval West: Problems and Opportunities,” in Europa medie- vale e mondo bizantino. Contatti effettivi e possibilita` degli studi comparati, Tavola rotonda del XVIII Congresso del CISH-Montre´al, 29 agosto 1995, ed. -

Celator Index

AUTHOR TITLE / ABSTRACT DATE VOL: PAGE Album, Stephen Radical reform led to a truly Islamic style of coinage Jan., 1989 02:01 1 Album, Stephen Calligraphers created dies for Islamic coinage Feb., 1988 02:02 1 Album, Stephen Islamic conquerors adapted local Byzantine coinage April, 1988 02:04 1 Album, Stephen Sasanian motifs used in Islamic coinage July, 1988 02:07 1 Album, Stephen Arab-Sasanian copper presents varied typology Aug., 1988 02:08 1 Album, Stephen Umayyad and Abbasid relationship is rethought ( Pt 1 ) June, 1989 03:06 1 Album, Stephen Umayyad and Abbasid relationship is rethought (Pt 2) July, 1989 03:07 1 Album, Stephen Abbassid overthrow resulted in changed coinage Oct., 1989 03:10 1 Album, Stephen Political and fiscal elements influence coinage Nov., 1989 03:11 1 Album, Stephen Deterioration of caliphate power traced in coinage Dec., 1989 03:12 1 Arrigoni, Marco F. Coinage offers insight into the history of Tacitus and the Interregnum period Aug., 1997 11:08 6 Assar, G.R. Dr. Ancient coin grading and description Aug., 1998 12:08 36 Barton, John L. Byzantine emperor links present to past Aug/Sep., 1987 01:04 1 Barton, John L. Quality coin photos Dec., 1987 01:06 1 Barton, John L. Judaean history is traced with coins Feb., 1988 02:02 1 Barton, John L. Necessity played key role in Roman coin changes July, 1988 02:07 1 Beckman, Martin Numismatics and the antiquities trade May, 1998 12:05 34 Bedoukian/Saryan Roman coins and medals relating to Armenia (Ch. 1) March, 1998 12:03 6 Bedoukian/Saryan Roman coins and medals relating to Armenia (Ch.