Learning from Lai Changxing? Jeremy Brown Simon Fraser University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

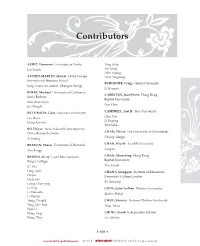

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Paper by Professor ZHAO Bingzhi, Dean, College for Criminal Law

Paper by Professor ZHAO Bingzhi, Dean, College for Criminal Law Science and School of Law, Beijing Normal University and President, Criminal Law Research Committee, China Law Society, Mainland China Criminal Legality in Mainland China’s 30 Years of Reform and Opening-up — Perspective from a Number of Typical Cases (Translation of original speech in Chinese) Table of Contents Preamble I. Outline of the criminal legality prior to the promulgation and implementation of the 1997 Penal Code (1978-1997) (I) Lin Biao & Jiang Qing Counter-revolutionary Group Case (II) Han Kun Bribe-taking Case (III) Jiang Aizhen Intentional Homicide Case (IV) December Eighth Karamai City (Xinjiang) Major Liability Incident & Negligence of Duty Case II. Outline of the criminal legality subsequent to the promulgation and implementation of the 1997 Penal Code (1997-2008) (I) Zhang Ziqiang Case (II) Gong Jianping Football “Black Whistle” Case (III) Zheng Xiaoyu Bribe-taking & Negligence of Duty Case (IV) Xu Ting Theft Case (V) Several Typical Cases with Criminal Fled Away (Yu Zhendong Case, Hu Xing Case and Lai Changxing Case) Conclusion Preamble The reform and opening-up cause of China has witnessed a 30-year splendid and brilliant course since the third plenary session of the 11th Central Committee in December 1978. The 30 years of reform and opening-up was accompanied with the 30 years of hardships and explorations, the 30 years of fluctuations and transitions and the 30 years of advancements within each passing day. We have, during these 30 years of reform and opening-up, gone through earthshaking social developments and changes and have acquired spectacular achievements to which worldwide attention was drawn. -

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China

The Prevention and Control of Economic Crime in China: A Critical Analysis of the Law and its Administration Enze Liu Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Advanced Legal Studies School of Advanced Study, University of London September 2017 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis represents my own work. Where information has been used they have been duly acknowledged. Signature: …………………………. Date: ………………………………. 2 Abstract Economic crime and corruption has been an issue throughout Chinese history. While there may be scope for discussion as to the significance of public confidence in the integrity of a government, in practical terms the government of China has had to focus attention on maintaining confidence in its integrity as an issue for stability. Since the establishment of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and its assumption of power and in particular after the ‘Opening’ of the Chinese economy, abusive conduct on the part of those in positions of privilege, primarily in governmental organisations, has arguably reached an unprecedented level. In turn, this is impeding development as far as it undermines public confidence, accelerates jealousy and forges an even wider gap between rich and poor, thereby threatening the stability and security of civil societies. More importantly, these abuses undermine the reputation of the CCP and the government. China naturally consider this as of key significance in attracting foreign investment and assuming its leading role in the world economy. While there have been many attempts to curb economic crime, the traditional capabilities of the law and particularly the criminal justice system have in general terms been found to be inadequate. -

1 Annotated Bibliography of Liu Xiaobo's Texts in Chronological Order

1 Annotated Bibliography of Liu Xiaobo’s Texts in Chronological Order Year Chinese Title English Title Category 04/1984 艺术直觉 On Artistic Intuition 关系学院 学 1 1984 庄子 On Zhuangzi 社科学战线 05/1985 和冲突 – 中西美意的差别 Harmony and Conflicts – Differences between Chinese 京师范大学 and Western Aesthetics 学 07/1985 味觉说 Theory of Taste 科知 Early 1986 种的美思潮 – 徐星陈村索拉的 A New Aesthetic Trend – Remarks Inspired by the Works 文学 2 部作谈起 of Xu Xing, Chen Cun and Liu Suola (1986:3) 04/1986 无法回避的思 – 几部关知子的小说 Unavoidable Reflection – Contemplating Stories on 中 / MA 谈起 Intellectuals (EN 94) Thesis 03/10/1986 机,时期文学面临机 Crisis! New Era’s Literature is Facing a Crisis (FR) 深圳青 10/1986 李厚对 – Dialogue with Li Zehou (1) 中 1986 On Solitude (EN) 家 1988:2 1 th Zhuangzi was a Chinese Daoist thinker who lived around the 4 century BC during the Warring States period, when the Hundred Schools of Thought flourished. 2 Shanghai writer Chen Cun (1954-) and Beijing writers Liu Suola (1955-) and Xu Xing (1956-) who expressed contempt for the formal education of the mid-1980s and its pretention. Liu Xiaobo responded to a conservative attack on 'superfluous people' by defending these three writers who were popular in 1985 and who would be also attacked in 1990 as “rebellious aristocrats” whose works displayed a “liumang mentality.” He wrote a positive interpretation of their way of “ridiculing the sacred, the lofty and commonly valued standards and traditional attitude.” He also drew a connection between traditional “individualists” such as Zhuangzi, the poet Tao Yuanming (365-427 CE) and the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove (竹林七) as related to this modem trend of irreverence. -

China Helped Block Fugitive's Cash

DESKEDT SCM,2001-07-19,1,SCM,3,SECOND EDITION COLOUR BLACK C5 ad1 27x5, The Peninsula (Page 3) - Thu Jul 19 01:01:24 2001 - Job7169776 SOUTH CHINA MORNING POST THURSDAY JULY 19 2001 HONG KONG 3 Top health China helped block fugitive’s cash inspector Documents show Beijing leaned on Turkish-controlled Cyprus to freeze account held by wife of ‘kingpin’ badly hurt Michael Chugani in Seattle Frozen assets in attack China exerted political pressure How Lai Changxing’s money ended up trapped in a northern Cyprus bank Clifford Lo to make a bank in Turkish-con- trolled Cyprus freeze a US$1 mil- US$2million US$1.6 million US$1million lion (HK$7.8 million) account A chief health inspector who led held by the wife of alleged smug- frontline campaigns to shut down gling kingpin Lai Changxing, doc- illegal slaughterhouses was criti- Sale of property Banque Nationale HSBC, Renfrew Security uments obtained by the South cally ill last night after being blud- development in China de Paris, Singapore Vancouver Bank and Trust China Morning Post suggest. geoned by three men. The documents show the off- October 19, 1999: Renfrew Security Bank to Lai’s wife, Tsang Mingna Wong Wai-wan, 46, underwent shore Renfrew Security Bank and brain surgery in Tuen Mun Hos- Trust froze the account on the pital after the attack, which hap- grounds that it may contain laun- pened as he made his way to his dered money from Hong Kong. Yuen Long office. Other documents show the Detectives were investigating funds were transferred to the whether the attack on the Food bank in the Turkish-controlled and Environmental Hygiene De- part of Cyprus from a Vancouver partment official was linked to his HSBC branch. -

An Assessment of Stephen Harper's China Policy

CANADIAN FORCES COLLEGE / COLLÈGE DES FORCES CANADIENNES JCSP 36 / PCEMI 36 Master of Defence Studies Even Dief’ Sold Wheat: An Assessment of Stephen Harper’s China Policy By/par Lieutenant-Commander Todd Bonnar This paper was written by a student attending La présente étude a été rédigée par un stagiaire the Canadian Forces College in fulfilment of one du Collège des Forces canadiennes pour of the requirements of the Course of Studies. satisfaire à l'une des exigences du cours. L'étude The paper is a scholastic document, and thus est un document qui se rapporte au cours et contains facts and opinions, which the author contient donc des faits et des opinions que seul alone considered appropriate and correct for l'auteur considère appropriés et convenables au the subject. It does not necessarily reflect the sujet. Elle ne reflète pas nécessairement la policy or the opinion of any agency, including politique ou l'opinion d'un organisme the Government of Canada and the Canadian quelconque, y compris le gouvernement du Department of National Defence. This paper Canada et le ministère de la Défense nationale may not be released, quoted or copied, except du Canada. Il est défendu de diffuser, de citer ou with the express permission of the Canadian de reproduire cette étude sans la permission Department of National Defence. expresse du ministère de la Défense nationale. Word Count: 18,208 Compte de mots : 18, 208 i ABSTRACT The weak legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) owing to 25 years of market reform and the opening of the country to the world economy has radically transformed the Chinese society. -

The Honourable Mr. Justice De Montigny

Date: 20070405 Docket: IMM-2669-06 Citation: 2007 FC 361 Ottawa, Ontario, April 5, 2007 PRESENT: The Honourable Mr. Justice de Montigny BETWEEN: LAI CHEONG SING and TSANG MING NA Applicants and THE MINISTER OF CITIZENSHIP AND IMMIGRATION Respondent REASONS FOR ORDER AND ORDER [1] The applicants Lai Cheong Sing and Tsang Ming Na have applied for judicial review of a PRRA officer’s decision rejecting their PRRA application. The Chinese government has accused the Lais of masterminding a massive smuggling and bribery operation. It wants the couple returned home to face prosecution for their alleged crimes. The Lais, for their part, have consistently maintained that China has fabricated all the allegations against them. [2] Mr. Lai, his ex-wife Ms. Tsang (they are now divorced), and their three children claimed refugee status in June 2000. After a 45-day hearing, the Immigration and Refugee Board’s Refugee Division (the Board) found the parents were excluded from Convention refugee status under Article 1F(b) of the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (the Convention). In any case, the Board also found the parents were not Convention refugees, because there was no nexus between their claims and any Convention refugee grounds. The Board described the couple as criminals fleeing from justice, not persecution. The children’s claims were based on their parents’, and failed accordingly. [3] In their PRRA application, the Lais made submissions alleging bias, Charter violations, and breaches of procedural fairness. Their submissions on risk included a number of challenges to the Chinese legal system. They maintained the same theory they raised at their Board hearing. -

Ex-Top Fugitive Lai Confesses to Smuggling

Shanghai Daily Saturday 31 December 2011 www.shanghaidaily.com TOP NEWS A3 Ex-top fugitive Lai confesses to smuggling Liang Yiwen enforcement cooperation, the public security ministry said. ALLEGED smuggling kingpin Lai Lai had avoided deportation by Changxing, once the No. 1 fugitive arguing he could face the death pen- at the center of China’s biggest cor- alty or be tortured and would not get ruption scandal, has confessed to trafficking and bribery charges and a fair trial in his home country. But that legal battle ended when a federal From left: Singers Harlem Yu, Tanya Chua, Mavis Fan and Willber Pan show their hand prints yesterday his case has been handed over for court in Vancouver ruled Lai should during a press conference for tonight’s countdown ceremony in the Xintiandi area. — Zhang Xinyan prosecution, the customs department and prosecutors in southeastern Fujian not be considered a refugee and upheld Province announced yesterday. his deportation, AP said. Lai, 53, became China’s most-want- According to earlier reports, China New Year’s Eve festivities, ed man after he fled to Canada in 1999 promised Canada that Lai would not and fought extradition for 12 years get the death penalty in 2001 when until he was deported in July. After then-President Jiang Zemin sent the he was extradited to China, he was ar- Canadian prime minister at the time deals set at city tourist spots Jean Chretien a diplomatic note. rested and investigated for smuggling and bribery. Before fleeing to Canada, Lai lived Staff Reporters own countdown plans and will Where you can go tonight to Thirty-one criminal suspects be- a life of luxury in China complete stay alight until after midnight. -

Clive Ansley Submission Report

REPORT FOR THE INDEPENDENT TRIBUNAL INTO FORCED ORGAN HARVESTING OF PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE IN CHINA Submitted by Clive Ansley CONTENTS CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................. 1 A. PROFESSIONAL BACKGROUND......................................................................................................... 2 B. BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................................6 C. UNFAIR TRIAL, LACK OF INDEPENDENT JUDICIARY, AND NO PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE. 10 – FAIR TRIAL ....................................................................................................................................10 – DOES THE PRESUMPTION OF INNOCENCE APPLY IN CHINESE CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS? 13 – WHAT IS THE CONVICTION RATE IN CHINESE CRIMINAL COURTS? .....................................16 – JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE ........................................................................................................17 D. THE OPERATION OF THE POLICE AND OTHER LAW ENFORCEMENT AGENCIES IN CHINA.... 27 E. UNTRUTHFUL EVIDENCE................................................................................................................... 34 F. HOW IS EVIDENCE GATHERED TO PREPARE WARRANTS FOR ARREST? ARE STATEMENTS BY INFORMANTS VOLUNTARY OR THE RESULT OF POLICE COERCION? HOW RELIABLE ARE CHINESE WARRANTS AS EVIDENCE OF THE FACTS THAT THEY ALLEGE? ...................................36 -

Is Xi Jinping the Reformist Leader China Needs?

China Perspectives 2012/3 | 2012 Locating Civil Society Is Xi Jinping the Reformist Leader China Needs? Jean-Pierre Cabestan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5969 DOI: 10.4000/chinaperspectives.5969 ISSN: 1996-4617 Publisher Centre d'étude français sur la Chine contemporaine Printed version Date of publication: 1 October 2012 Number of pages: 69-76 ISSN: 2070-3449 Electronic reference Jean-Pierre Cabestan, « Is Xi Jinping the Reformist Leader China Needs? », China Perspectives [Online], 2012/3 | 2012, Online since 01 October 2015, connection on 15 September 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/chinaperspectives/5969 © All rights reserved Current affairs China perspectives Is Xi Jinping the Reformist Leader China Needs? JEAN-PIERRE CABESTAN ABSTRACT: In autumn 2012, following the 18th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Xi Jinping is to succeed Hu Jintao as General Secretary of the Party and also, in all probability, as Chairman of the Central Military Commission, where he has been second-in-command since 2010. In March 2013, he is set to become President of the People’s Republic of China. Born into the political elite, he enjoys a great deal of support in the Nomenklatura. Having governed several coastal provinces, the current Vice-President is thoroughly acquainted with the workings of Party and state. He also has support within the Army, where he spent a short time at the beginning of his career. In addition, in recent years, he has acquired significant international experience. Urbane and affable, Xi is appreciated for his consensual approach. Nonetheless, Xi is taking charge of the country at a particularly delicate time. -

The People's Liberation Army General Political Department

The People’s Liberation Army General Political Department Political Warfare with Chinese Characteristics Mark Stokes and Russell Hsiao October 14, 2013 Cover image and below: Chinese nuclear test. Source: CCTV. | Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Political Warfare | About the Project 2049 Institute Cover image source: 997788.com. Above-image source: ekooo0.com The Project 2049 Institute seeks to guide Above-image caption: “We must liberate Taiwan” decision makers toward a more secure Asia by the century’s mid-point. The organization fills a gap in the public policy realm through forward-looking, region- specific research on alternative security and policy solutions. Its interdisciplinary approach draws on rigorous analysis of socioeconomic, governance, military, environmental, technological and political trends, and input from key players in the region, with an eye toward educating the public and informing policy debate. www.project2049.net 1 | Chinese Peoples’ Liberation Army Political Warfare | TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….……………….……………………….3 Universal Political Warfare Theory…………………………………………………….………………..………………4 GPD Liaison Department History…………………………………………………………………….………………….6 Taiwan Liberation Movement…………………………………………………….….…….….……………….8 Ye Jianying and the Third United Front Campaign…………………………….………….…..…….10 Ye Xuanning and Establishment of GPD/LD Platforms…………………….……….…….……….11 GPD/LD and Special Channel for Cross-Strait Dialogue………………….……….……………….12 Jiang Zemin and Diminishment of GPD/LD Influence……………………….…….………..…….13 -

Asian Organized Crime and Terrorist Activity in Canada, 1999-2002

ASIAN ORGANIZED CRIME AND TERRORIST ACTIVITY IN CANADA, 1999-2002 A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the United States Government July 2003 Researcher: Neil S. Helfand Project Manager: David L. Osborne Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540−4840 Tel: 202−707−3900 Fax: 202−707−3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Asian Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Canada PREFACE This study is based on open source research into the scope of Asian organized crime and terrorist activity in Canada during the period 1999 to 2002, and the extent of cooperation and possible overlap between criminal and terrorist activities in that country. The analyst examined those Asian organized crime syndicates that direct their criminal activities at the United States via Canada, namely crime groups trafficking heroin from Southeast Asia, groups engaging in the trafficking of women, and groups committing financial crimes against U.S. interests. The terrorist organizations examined were those that are viewed as potentially planning attacks on U.S. interests. The analyst researched the various holdings of the Library of Congress, the Open Source Information System (OSIS), other press accounts, and various studies produced by scholars and organizations. Numerous other online research services were also used in preparing this study, including those of NGOs and international organizations. i Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Asian Criminal and Terrorist Activity in Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE.......................................................................................................................................