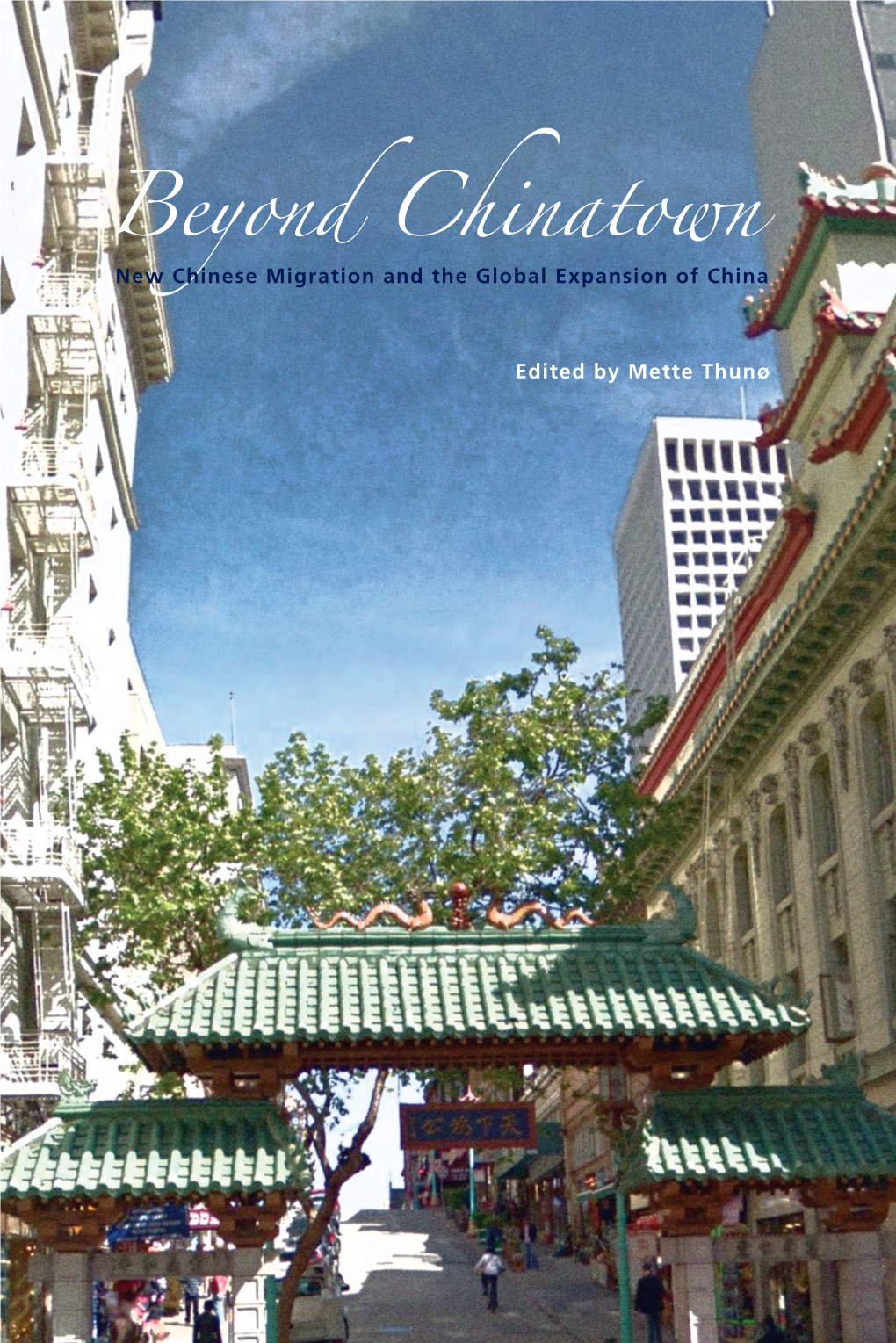

Introduction Beyond 'Chinatown': Contemporary Chinese Migration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

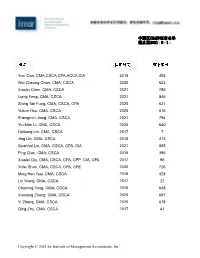

中国区cma持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日

中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Yixu Cao, CMA,CSCA,CPA,ACCA,CIA 2019 492 Wai Cheung Chan, CMA, CSCA 2020 622 Xiaolin Chen, CMA, CSCA 2021 785 Liang Feng, CMA, CSCA 2021 845 Shing Tak Fung, CMA, CSCA, CPA 2020 621 Yukun Hsu, CMA, CSCA 2020 676 Shengmin Jiang, CMA, CSCA 2021 794 Yiu Man Li, CMA, CSCA 2020 640 Huikang Lin, CMA, CSCA 2017 7 Jing Lin, CMA, CSCA 2018 415 Quanhui Liu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CIA 2021 855 Ping Qian, CMA, CSCA 2018 396 Xiaolei Qiu, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFP, CIA, CFA 2017 96 Yufei Shan, CMA, CSCA, CPA, CFE 2020 726 Ming Han Tsai, CMA, CSCA 2018 428 Lin Wang, CMA, CSCA 2017 22 Chunling Yang, CMA, CSCA 2020 648 Xiaolong Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 697 Yi Zhang, CMA, CSCA 2020 678 Qing Zhu, CMA, CSCA 2017 41 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. 中国区CMA持证者名单 截止至2021年9月1日 Siha A, CMA 2020 81134 Bei Ai, CMA 2020 84918 Danlu Ai, CMA 2021 94445 Fengting Ai, CMA 2019 75078 Huaqin Ai, CMA 2019 67498 Jie Ai, CMA 2021 94013 Jinmei Ai, CMA 2020 79690 Qingqing Ai, CMA 2019 67514 Weiran Ai, CMA 2021 99010 Xia Ai, CMA 2021 97218 Xiaowei Ai, CMA, CIA 2019 75739 Yizhan Ai, CMA 2021 92785 Zi Ai, CMA 2021 93990 Guanfei An, CMA 2021 99952 Haifeng An, CMA 2021 92781 Haixia An, CMA 2016 51078 Haiying An, CMA 2021 98016 Jie An, CMA 2012 38197 Jujie An, CMA 2018 58081 Jun An, CMA 2019 70068 Juntong An, CMA 2021 94474 Kewei An, CMA 2021 93137 Lanying An, CMA, CPA 2021 90699 Copyright © 2021 by Institute of Management Accountants, Inc. -

Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society

The London School of Economics and Political Science Performing Masculinity in Peri-Urban China: Duty, Family, Society Magdalena Wong A thesis submitted to the Department of Anthropology of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London December 2016 1 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/ PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 97,927 words. Statement of use of third party for editorial help I confirm that different sections of my thesis were copy edited by Tiffany Wong, Emma Holland and Eona Bell for conventions of language, spelling and grammar. 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how a hegemonic ideal that I refer to as the ‘able-responsible man' dominates the discourse and performance of masculinity in the city of Nanchong in Southwest China. This ideal, which is at the core of the modern folk theory of masculinity in Nanchong, centres on notions of men's ability (nengli) and responsibility (zeren). -

Asian Languages in the Australian Education System

The Study of Asian Languages in Two Australian States: Considerations for Language-in-Education Policy and Planning Yvette Slaughter Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2007 School of Languages and Linguistics University of Melbourne ABSTRACT This dissertation conducts a comprehensive examination of the study of Asian languages in two Australian states, taking into consideration the broad range of people and variables which impact on the language-in-education ecology. These findings are intended to enhance the development of language-in-education policy, planning and implementation in Australia. In order to incorporate a number of perspectives in the language-in-education ecology, interviews were conducted with a range of stakeholders, school administrators, LOTE (Languages Other Than English) coordinators and LOTE teachers, from all three education systems – government, independent and Catholic (31 individuals), across two states – Victoria and New South Wales. Questionnaires were also completed by 464 senior secondary students who were studying an Asian language. Along with the use of supporting data (for example, government reports and newspaper discourse analysis), the interview and questionnaire data was analysed thematically, as well as through the use of descriptive statistics. This study identifies a number of sociopolitical, structural, funding and attitudinal variables that influence the success of Asian language program implementation. An interesting finding to arise from the student data is the notion of a pan-Asian identity amongst students with an Asian heritage. At a broader level, the analysis identifies different outcomes for the study of Asian languages amongst schools, education and systems as a result of the many factors that are a part of the language-in-education ecology. -

Multiculturalism in Action Presents

Multiculturalism in Action presents Multiculturalism in Action Project is a community outreach program to promote cross-cultural awareness and appreciation among different ethnic groups in Hong Kong. Visit our website below to access our information kits for free: http://arts.cuhk.edu.hk/~ant/knowledge-transfer/multiculturalism-in- action/index.html Enquiries are welcome! South Asians in Hong Kong South Asia is a geographical concept which refers to countries located in the Southern part of Asia, including: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka. Ethnicity Number % Indian 28,616 0.4% Pakistani 18,042 0.3% Nepali 16,518 0.2% Other Asians (including 7038 0.09% The 2011 Census shows Bangladeshis and that South Asians make up Sri Lankans) about 1% of the Hong Kong Source: 2011 Census population History South Asians first settled in Hong Kong in the 19th century. They were Indians who came as police, soldiers, as well as traders in tea, textile, and jewellery, among others. With the independence of Pakistan in 1947, and of Bangladesh in 1971, Hong Kong began to have its Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities. Copyright © Multiculturalism in Action Project 2016 1 The history of Nepalis in Hong Kong can be traced to the stationing of the Gurkha regiments in the British Army in 1948. Their four main duties included border control, internal security, explosive ordnance disposal, and sea support. “Trailwalker” and “Hike for Hospice” are charitable activities started by the Gurkhas. Ex-Gurkhas observing Remembrance Day in Hong Kong Nowadays, South Asian women and men are employed in different occupations in Hong Kong. -

Compassion & Social Justice

COMPASSION & SOCIAL JUSTICE Edited by Karma Lekshe Tsomo PUBLISHED BY Sakyadhita Yogyakarta, Indonesia © Copyright 2015 Karma Lekshe Tsomo No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the editor. CONTENTS PREFACE ix BUDDHIST WOMEN OF INDONESIA The New Space for Peranakan Chinese Woman in Late Colonial Indonesia: Tjoa Hin Hoaij in the Historiography of Buddhism 1 Yulianti Bhikkhuni Jinakumari and the Early Indonesian Buddhist Nuns 7 Medya Silvita Ibu Parvati: An Indonesian Buddhist Pioneer 13 Heru Suherman Lim Indonesian Women’s Roles in Buddhist Education 17 Bhiksuni Zong Kai Indonesian Women and Buddhist Social Service 22 Dian Pratiwi COMPASSION & INNER TRANSFORMATION The Rearranged Roles of Buddhist Nuns in the Modern Korean Sangha: A Case Study 2 of Practicing Compassion 25 Hyo Seok Sunim Vipassana and Pain: A Case Study of Taiwanese Female Buddhists Who Practice Vipassana 29 Shiou-Ding Shi Buddhist and Living with HIV: Two Life Stories from Taiwan 34 Wei-yi Cheng Teaching Dharma in Prison 43 Robina Courtin iii INDONESIAN BUDDHIST WOMEN IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Light of the Kilis: Our Javanese Bhikkhuni Foremothers 47 Bhikkhuni Tathaaloka Buddhist Women of Indonesia: Diversity and Social Justice 57 Karma Lekshe Tsomo Establishing the Bhikkhuni Sangha in Indonesia: Obstacles and -

The Chinese in Hawaii: an Annotated Bibliography

The Chinese in Hawaii AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY by NANCY FOON YOUNG Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii Hawaii Series No. 4 THE CHINESE IN HAWAII HAWAII SERIES No. 4 Other publications in the HAWAII SERIES No. 1 The Japanese in Hawaii: 1868-1967 A Bibliography of the First Hundred Years by Mitsugu Matsuda [out of print] No. 2 The Koreans in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Arthur L. Gardner No. 3 Culture and Behavior in Hawaii An Annotated Bibliography by Judith Rubano No. 5 The Japanese in Hawaii by Mitsugu Matsuda A Bibliography of Japanese Americans, revised by Dennis M. O g a w a with Jerry Y. Fujioka [forthcoming] T H E CHINESE IN HAWAII An Annotated Bibliography by N A N C Y F O O N Y O U N G supported by the HAWAII CHINESE HISTORY CENTER Social Science Research Institute • University of Hawaii • Honolulu • Hawaii Cover design by Bruce T. Erickson Kuan Yin Temple, 170 N. Vineyard Boulevard, Honolulu Distributed by: The University Press of Hawaii 535 Ward Avenue Honolulu, Hawaii 96814 International Standard Book Number: 0-8248-0265-9 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-620231 Social Science Research Institute University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 Copyright 1973 by the Social Science Research Institute All rights reserved. Published 1973 Printed in the United States of America TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD vii PREFACE ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xi ABBREVIATIONS xii ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 1 GLOSSARY 135 INDEX 139 v FOREWORD Hawaiians of Chinese ancestry have made and are continuing to make a rich contribution to every aspect of life in the islands. -

Vietnamese Lexicography

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 302 082 FL 017 724 AUTHOR Dinh-Hoa, Nguyen TITLE Vietnamese Lexicography. PUB DATE Aug 87 NOTE 8p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Association of Applied Linguistics (8th, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia, August 16-21, 1987). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070) -- Historical Materials (060) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PCO1 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Diachronic Linguistics; Epistemology; Foreign Countries; *Lexicography; *Monolingualism; *Multilingualism; Romanization; *Vietnamese IDENTIFIERS *Vietnam ABSTRACT The-history of lexicography in Vietnam is chronicled from early Chinese and pissionary scholarship through the colonial period (1884-1946), the War years (1946-1954), the partition period (19541975), and the post-1975 period. The evolution of romanization, political-linguistic-influences, native scholarship in lexicography, and dictionary types art discussed, and successive tendencies in monolingual and multilingual dictionary development are highlighted. (MSE) ********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** 1 1E-4iTragietigs SOWNWEARlISTegngigita "PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE THIS U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION MATERIAL HAS BEEN GRANTED BY VIETNAMESELEXICOGRAPHY Office of Educanonai Research and Improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) Vitus document has been reproduced -

Chinese Influences in Philippine Culture

Miclat FEATURE ARTICLE Tradition, Misconception, and Contribution: Chinese Influences in Philippine Culture Maningning C. Miclat ABSTRACT This paper discusses Chinese influence on Philippine arts and crafts, as shown in artifacts from the Sino-Philippine trade of pre-Hispanic times—the churches, religious icons, and paintings of the Spanish period— and in the contemporary art of the Chinese Filipinos. The Chinese traditional elements are given new meanings in a new environment, and it is these misconceptions and misinterpretations of the imported concepts that influence and enrich our culture. THE PRE-HISPANIC PAST The Sino-Philippine trade is believed to have begun in AD 982. The History of the Sung Dynasty or Sung Shi, published in 1343- 1374, confirmed that trade contact started during the 10th century. A 13th century Sung Mandarin official, Chau Ju-kua, wrote a geographical work entitled “A Description of Barbarous Peoples” or Chu Fan Chi, the first detailed account on Sino-Philippine trade. The 14th century account of Ma Tulin entitled “A General Investigation of Chinese Cultural Sources” or Wen Shiann Tung Kuo referred to the Philippines as Ma-i.1 The presence of trade is further proven by the Oriental ceramics from China, Vietnam, and Thailand that have been excavated from many places in the archipelago (Zaide: 1990). The Chinese came to the Philippines and traded with the natives peacefully, exchanging Chinese goods with hardwood, pearls, and turtle shells that were valued in China. Traditional Chinese motifs that symbolize imperial power are found in the trade ceramics found in the Philippines. These are the 100 Humanities Diliman (July-December 2000) 1:2, 100-8 Tradition, Misconception, and Contribution dragon and the phoenix; auspicious emblems of prosperity, long life, and wealth, such as fishes, pearls, and blossoms, like peonies; and the eight precious things or Pa Bao, namely, jewelry, coins, open lozenges with ribbons, solid lozenges with ribbons, musical stones, a pair of books, a pair of horns, and the Artemisia leaf. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 20 July 2018

United Nations A/73/205 General Assembly Distr.: General 20 July 2018 Original: English Seventy-third session Item 74 (b) of the preliminary list* Promotion and protection of human rights: human rights questions, including alternative approaches or improving the effective enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms Effective promotion of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities Note by the Secretary-General The Secretary-General has the honour to transmit to the members of the General Assembly the report of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues, Fernand de Varennes, submitted pursuant to Assembly resolution 72/184 and Human Rights Council resolution 25/5. __________________ * A/73/50. 18-12048 (E) 010818 *1812048* A/73/205 Report of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues Statelessness: a minority issue Summary The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on minority issues was established by the Commission on Human Rights in its resolution 2005/79. It was subsequently extended by the Human Rights Council, most recently in its resolution 34/6. In the present report, in addition to giving an overview of his activities, the Special Rapporteur tackles the issue of statelessness and explores why most of the world’s more than 10 million men, women and children who find themselves deprived of citizenship are persons belonging to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities. The Special Rapporteur presents the underlying causes and patterns that result in millions of minorities around the world losing or being denied citizenship out of all proportion. First, he investigates how and why certain minorities find themselves particularly affected, and even at times specifically targeted, by legislation, policies and practices contributing to or resulting in statelessness. -

1 Remittances for Collective Consumption and Social Status Compensation

Remittances for Collective Consumption and Social Status Compensation: Variations on Transnational Practices among Chinese International Migrants1 Min Zhou and Xiangyi Li (Forthcoming International Migration Review) INTRODUCTION Economic reform in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) since the late 1970s has revitalized diaspora-homeland ties and created new opportunities for immigrant transnationalism. Hundreds and thousands of Chinese migrants who have resettled in different parts of the world are returning to their ancestral homeland to capitalize on new economic opportunities. While they have contributed significantly to China’s economic development via foreign direct investment and to the economic well- being of left-behind families through monetary and in-kind remittances, these migrants have also donated money to their hometowns to build or renovate symbolic structures (e.g., village gates, monuments, religious statues or altars in public space), educational institutions (e.g., schools and libraries), and other cultural facilities (e.g., ancestral halls, cultural centers, museums, and public parks). We refer to these monetary donations as “remittances for collective consumption.” Our current study contributes to the existing literature by focusing on this special type of migrant remittances. In China, remittances for collective consumption have left an indelible imprint on the physical landscape of migrant hometowns and villages, which not only serves to extol success stories of compatriots abroad but also helps boost the positive image of the hometown as simultaneously a nostalgic place for personal association and a transnational place for economic investment (Chen 2005; Kuah 2000; Li and Zhou 2012; Smart and Lin 2007; Taylor et al. 2003; Woon 1990). From our observation, however, some hometowns flourish with steady flows of remittances to build symbolic structures and cultural facilities, while others decline with few such remittances. -

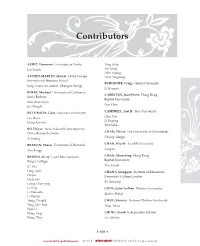

Contributors.Indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM F-479 /203/BER00069/Work/Indd/%20Backmatter

02_Contributors.indd Page 569 10/20/15 8:21 AM f-479 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter Contributors AUBIÉ, Hermann University of Turku Yang Jiang Liu Xiaobo Yao Ming Zhao Ziyang AUSTIN-MARTIN, Marcel China Europe Zhou Youguang International Business School BURGDOFF, Craig Capital University Jiang Zemin (co-author: Zhengxu Wang) Li Hongzhi BERRY, Michael University of California, CABESTAN, Jean-Pierre Hong Kong Santa Barbara Baptist University Hou Hsiao-hsien Lien Chan Jia Zhangke CAMPBELL, Joel R. Troy University BETTINSON, Gary Lancaster University Chen Yun Lee, Bruce Li Keqiang Wong Kar-wai Wen Jiabao BO Zhiyue New Zealand Contemporary CHAN, Felicia The University of Manchester China Research Centre Cheung, Maggie Xi Jinping BRESLIN, Shaun University of Warwick CHAN, Hiu M. Cardiff University Zhu Rongji Gong Li BROWN, Kerry Lau China Institute, CHAN, Shun-hing Hong Kong King’s College Baptist University Bo Yibo Zen, Joseph Fang Lizhi CHANG Xiangqun Institute of Education, Hu Jia University College London Hu Jintao Fei Xiaotong Leung Chun-ying Li Peng CHEN, Julie Yu-Wen Palacky University Li Xiannian Kadeer, Rebiya Li Xiaolin Tsang, Donald CHEN, Szu-wei National Taiwan University Tung Chee-hwa Teng, Teresa Wan Li Wang Yang CHING, Frank Independent Scholar Wang Zhen Lee, Martin • 569 • www.berkshirepublishing.com © 2015 Berkshire Publishing grouP, all rights reserved. 02_Contributors.indd Page 570 9/22/15 12:09 PM f-500 /203/BER00069/work/indd/%20Backmatter • Berkshire Dictionary of Chinese Biography • Volume 4 • COHEN, Jerome A. New -

Drug Trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle

Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy To cite this version: Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy. Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle. An Atlas of Trafficking in Southeast Asia. The Illegal Trade in Arms, Drugs, People, Counterfeit Goods and Natural Resources in Mainland, IB Tauris, p. 1-32, 2013. hal-01050968 HAL Id: hal-01050968 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01050968 Submitted on 25 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Atlas of Trafficking in Mainland Southeast Asia Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy CNRS-Prodig (Maps 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 25, 31) The Golden Triangle is the name given to the area of mainland Southeast Asia where most of the world‟s illicit opium has originated since the early 1950s and until 1990, before Afghanistan‟s opium production surpassed that of Burma. It is located in the highlands of the fan-shaped relief of the Indochinese peninsula, where the international borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand, run. However, if opium poppy cultivation has taken place in the border region shared by the three countries ever since the mid-nineteenth century, it has largely receded in the 1990s and is now confined to the Kachin and Shan States of northern and northeastern Burma along the borders of China, Laos, and Thailand.