Platy Limestone As Cultural Heritage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nosilna Zmogljivost Občine Komen Za Turizem

Univerza na Primorskem Fakulteta za turistične študije – Turistica Magistrsko delo NOSILNA ZMOGLJIVOST OBČINE KOMEN ZA TURIZEM Sara Baša Univerza na Primorskem Fakulteta za turistične študije – Turistica Magistrsko delo NOSILNA ZMOGLJIVOST OBČINE KOMEN ZA TURIZEM Izdelala: Sara Baša Mentor: izr. prof. dr. Igor Jurinčič Portorož, maj, 2020 PODATKI O MAGISTRSKEM DELU Avtor: Sara Baša Naslov: Nosilna zmogljivost Občine Komen za turizem Kraj: Portorož Leto: 2020 Število strani: 105 Število prilog: 1 Mentor: izr. prof. dr. Igor Jurinčič Somentor: / Lektorica: Mija Čuk, univ. dipl. spl. jez. Ključne besede: trajnostni razvoj turizma/Komen/nosilna zmogljivost/ UDK: 338.48-44(1-22) Avtorski izvleček: Predstavniki občine in drugi deležniki, ki se dnevno spopadajo z razvojem turizma v določeni občini, se morajo zavedati meja nosilne zmogljivosti okolja. Kot učinkovit se kaže model trajnostnega razvoja turizma, pomemben instrument načrtovanja turizma v določeni občini pa metoda nosilne zmogljivosti. Glavno vprašanje vsakega načrtovalca mora biti, kako razvijati turizem brez čezmernih vplivov na okolje, kar lahko prouči s podrobno analizo indikatorjev. Na podlagi ugotovitev se pri vsakem izmed devetih indikatorjev določi prag nosilne zmogljivosti in predlaga ukrepe za dvig nosilne zmogljivosti, preden se zmanjša turistični obisk in se preveč poseže v okolje. V Občini Komen je v zadnjih letih opaziti povečano rast števila turistov in nočitev, zato smo želeli preveriti, koliko turistov okolje lahko sprejme, da ostaja v dovoljenih mejah nosilne zmogljivosti. Analizirali smo devet indikatorjev iz prostorsko-ekološke skupine, infrastrukturne i skupine in ekonomske skupine. Za vsak indikator smo podali predloge znotraj trajnostnega razvoja turizma in ukrepe, kako postopati v prihodnje pri preseženih vrednostih. Ključnega pomena je vodenje turistične destinacije znotraj nosilne zmogljivosti. -

Urnik Odvoza Ostanka Komunalnih Odpadkov 2021 Občina Komen

URNIK ODVOZA OSTANKA KOMUNALNIH ODPADKOV 2021 OBČINA KOMEN Brestovica pri Komnu, Brje pri Komnu, Gorjansko, Ivanji Grad, Jablanec, Klanec pri Komnu, Majerji, Nadrožica, Preserje pri Komnu, Rubije, Sveto, Šibelji, Škrbina, Vale, Zagrajec Partizanska cesta 2 6210 Sežana 5. januar, 2. februar, 3. marec, 31. marec, 3. maj, 31. maj, 28. junij, 26. julij, 23. avgust, 20. september, 18. oktober, 16. november, 14. december URADNE URE IN KONTAKTI sreda 8h - 11h in 13h - 16h Coljava, Divči, Gabrovica pri Komnu, Komen, Mali Dol, Ško, Tomačevica, Volčji tel: 05 73 11 200 Grad fax: 05 73 11 201 [email protected] 7. januar, 4. februar, 8. marec, 6. april, 5. maj, 2. junij, 30. junij, 28. julij, 25. avgust, www.ksp-sezana.si 22. september, 20. oktober, 18. november, 16. december Ravnanje z odpadki: Čehovini, Čipnje, Dolanci, Hruševica, Kobdilj, Kobjeglava, Koboli, Kodreti, Lisjaki, 05 73 11 240 Lukovec, Štanjel, Trebižani, Tupelče, Večkoti Prijava - odjava: 05 73 11 245 4. januar, 1. februar, 2. marec, 30. marec, 29. april, 27. maj, 24. junij, 22. julij, 19. avgust, 16. september, 14. oktober, 15. november, 13. december Računi: 05 73 11 238 CERO SEŽANA (ob cesti Sežana - Vrhovlje) ODLAGAMO: v poletnem obdobju pometnine, vsebine sesalcev, (od 1.5. do 30.9.) kopalniške odpadke (higienski vložki, vsak delavnik od 6h do 19h plenice, vatirane palčke za čiščenje ušes, NE ODLAGAMO: v soboto od 8h do 13h vata, britvice ...), kuhinjske krpice in papirja, plastenk, plastične embalaže, gobice, manjše količine izrabljenih pločevink, stekla, nevarnih, kosovnih oblačil in obutve, manjše predmete iz v zimskem obdobju in gradbenih odpadkov, bio trde plastike (izrabljena pisala, (od 1.10. -

Gradišča — Utrjene Naselbine V Sloveniji

GRADIŠČA — UTRJENE NASELBINE V SLOVENIJI FRANC TRUHLAR Ljubljana V razgibanem geografskem položaju in političnem razvoju Slovenije, ki je pred stavljala v alpsko-jadranskem medprostoru vselej pomembno mednarodno stičišče in cestno križišče z magistralno povezavo panonskih in noriških pokrajin z jadranskim območjem in Italijo, so imela gradišča kot utrjene naselbinske postojanke v arheolo ških obdobjih določeno poselitveno-zgodovinsko vlogo. Okrog 600 doslej v Sloveniji evidentiranih »gradišč« spričuje pomemben naselitveni potencial Slovenije, od bronaste dobe do zgodnjega srednjega veka, z vzponom v kla sičnem halštatu in upadom v naslednjih obdobjih. Pozneje so nastajali včasih na gradiščih rimski kašteli, poganska svetišča, starokrščanske bazilike, srednjeveški gra dovi, tabori in svetišča ali nekatera sedanja naselja. V pretežno goratem svetu Slovenije z naravno zavarovano lego gradišč, ojačeno z obzidji, nasipi, jarki, okopi, je bila zagotovljena tudi varnost okolišnjih selišč. Večje gradiščne aglomeracije so bile povezane s potmi, ki so nekatere služile za osnovo po znejšega prometnega omrežja. Gradišča so bila trajno naseljena ali začasno uporabljena kot zatočišča za bližnja naselja. Poleg naselbinske so imela gradišča tudi obrambno funkcijo. Najbolj razširjeno in arheološko najbolj dognano krajevno ali ledinsko ime, ki gradišča označuje ali indicira, je prav oznaka Gradišče, z različnimi sestavljenkami in izpeljankami. (Glej še seznam toponima GradiščeANSI, v str. 106—112). Poleg naštetih toponimov označujejo ali indicirajo -

Komunalno Stanovanjsko Podjetje D. D. Partizanska Cesta 2, 6210 SEŽANA, Tel.: 05/73 11 200, Fax: 05/73 11 201 [email protected]

komunalno stanovanjsko podjetje d. d. Partizanska cesta 2, 6210 SEŽANA, tel.: 05/73 11 200, fax: 05/73 11 201 www.ksp-sezana.si, [email protected] gospodinjstva z individualnimi zabojniki JANUAR FEBRUAR MAREC APRIL P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 28 29 30 31 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 MAJ JUNIJ JULIJ AVGUST P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N 1 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 27 28 29 30 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 29 30 31 30 31 SEPTEMBER OKTOBER NOVEMBER DECEMBER P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N P T S Č P S N 12 3 4 1 2 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 28 29 30 26 27 28 29 30 31 31 V kolikor zabojnik na predvideni dan ni bil izpraznjen, ga pustite na prevzemnem mestu do izpraznitve. -

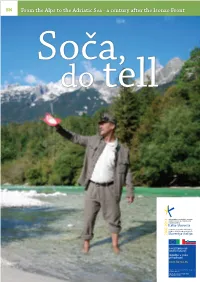

From the Alps to the Adriatic

EN From the Alps to the Adriatic Sea - a century after the Isonzo Front Soča, do tell “Alone alone alone I have to be in eternity self and self in eternity discover my lumnious feathers into afar space release and peace from beyond land in self grip.” Srečko Kosovel Dear travellers Have you ever embraced the Alps and the Adriatic with by the Walk of Peace from the Alps to the Adriatic Sea that a single view? Have you ever strolled along the emerald runs across green and diverse landscape – past picturesque Soča River from its lively source in Triglav National Park towns, out-of-the-way villages and open fireplaces where to its indolent mouth in the nature reserve in the Bay of good stories abound. Trieste? Experience the bonds that link Italy and Slove- nia on the Walk of Peace. Spend a weekend with a knowledgeable guide, by yourself or in a group and see the sites by car, on foot or by bicycle. This is where the Great War cut fiercely into serenity a century Tourism experience providers have come together in the T- ago. Upon the centenary of the Isonzo Front, we remember lab cross-border network and together created new ideas for the hundreds of thousands of men and boys in the trenches your short break, all of which can be found in the brochure and on ramparts that they built with their own hands. Did entitled Soča, Do Tell. you know that their courageous wives who worked in the rear sometimes packed clothing in the large grenades instead of Welcome to the Walk of Peace! Feel the boundless experi- explosives as a way of resistance? ences and freedom, spread your wings among the vistas of the mountains and the sea, let yourself be pampered by the Today, the historic heritage of European importance is linked hospitality of the locals. -

Easter Camp 2016

Kras,Easter Slovenia, March camp 21st - March 28th2016 In cooperation with Jan Kocbach (GPS analyst in Norwegian national team ) PRELIMINARY PROGRAM: Monday, March 21st: Technique focus AM: T1: Half of the training intro into karst terrain, the rest of the training contour-only training. Map: Ponikve (new map available from March 2016) PM: T2: Compass and map reading. Mix of corridor and line. Map Kazlje - Gradnje: Tuesday, March 22nd: Middle focus - handling karst AM: T3: Middle on reduced map (contours + some important features). Alternative (T3B): same middle course (T3) but with full map. PM: T4: Regular middle with SI in the morning. High intensity with SI & Analysis! Map for T3 & T4: Krajna vas - Veliki dol: Wednesday, March 23rd: Sprint Day on Adriatic coast AM: T5: Sprint Izola Map Izola: PM: T6: Sprint Koper High intensity with SI & Analysis! Map Koper: Thursday, March 24th: Route choice focus AM: T7: Training with long legs / route choice focus PM: T8: Short training day before competition. Choice of contour training and regular course. Map Povir-Divaška jama: Friday - Monday, 25th - 28th March: Easter4 orienteering event 4 fun stages in different types of karst terrain!www.easter4.com Monday - Monday, 21st - 28th March: Alternative training sessions 3 additional training sessions + T1 & T2 will be available from March 21st to March 28th. Maps: Zabavlje, Kazlje - Tomaj, Dutovlje, T1, T2 EVENING ANALYSIS SESSIONS WITH JAN KOCBACH: Evening analysis session 1: Wednesday evening (March 23rd): - Based on fast middle training in karst terrain Tuesday morning + reduced map middle Tuesday PM - You should upload your GPS-data to be part of the analysis! - Focus: "Running effective middle distance in karst terrain". -

Razvojni Program Podeželja Krasa in Brkinov

RAZVOJNI PROGRAM PODEŽELJA KRASA IN BRKINOV za območje občin Divača, Hrpelje- Kozina in Sežana za obdobje 2007- 2013 dopolnjen in noveliran 2008 RAZVOJNI PROGRAM PODEŽELJA KRASA IN BRKINOV za območje občin Divača, Hrpelje-Kozina in Sežana za obdobje 2007-2013, dopolnjen in noveliran 2008 (osnutek) PODATKI O PRIPRAVI PROGRAMA Prvi razvojni program za območje občin Divača, Hrpelje-Kozina in Sežana se je pričel pripravljati v skladu z JAVNIM RAZPISOM ZA SOFINANCIRANJE IZDELAVE RAZVOJNIH PROGRAMOV PODEŽELJA IN OBLIKOVANJE LOKALNIH AKCIJSKIH SKUPIN (LAS) v skladu s Predlogom Uredbe Sveta o podpori za razvoj podeželja iz Evropskega kmetijskega sklada za razvoj podeželja (EKSRP) za programsko obdobje 2007-2013 objavljenim dne 29.7.2006 v Uradnem listu št.71-72. Program se je tako pričel pripravljati oktobra 2005, priprava se je skladno z zahtevami razpisa zaključila oktobra 2006. Občine so se odločile, da bodo ta program dodelale glede na nove razvojne potrebe oziroma skladno s pojavom novih razvojnih projektov, zato se je prva dodelava pričela vršiti konec leta 2007 in se nadaljevala v letu 2008. Pripravljalec programa : Območna razvojna agencija Krasa in Brkinov Odgovorna oseba: Vlasta Sluban, direktorica Vodja projekta: Nataša Matevljič Sodelujoče organizacije pri pripravi programa : občina Hrpelje-Kozina, občina Divača, občina Sežana, Kmetijska svetovalna služba Sežana, Zavod za gozdove območna enota Sežana, Komunalno stanovanjsko podjetje d.d. Sežana, Kraški vodovod d.o.o. Sežana, dr.Marko Koščak, krajevne skupnosti na območju, različna društva na območju, prebivalstvo na območju Čas priprave in izdelave: leti 2007 in 2008 Pripravljavec RPP občin Divača, Hrpelje-Kozina in Sežana je Območna razvojna agencija Krasa in Brkinov 2 RAZVOJNI PROGRAM PODEŽELJA KRASA IN BRKINOV za območje občin Divača, Hrpelje-Kozina in Sežana za obdobje 2007-2013, dopolnjen in noveliran 2008 (osnutek) KAZALO 1 Uvod z opisom dosedanjih aktivnosti s področja razvoja str. -

Drinking Water Supply from Karst Water Resources (The Example of the Kras Plateau, Sw Slovenia)

ACTA CARSOLOGICA 33/1 5 73-84 LJUBLJANA 2004 COBISS: 1.01 DRINKING WATER SUPPLY FROM KARST WATER RESOURCES (THE EXAMPLE OF THE KRAS PLATEAU, SW SLOVENIA) OSKRBA S PITNO VODO IZ KRAŠKIH VODNIH VIROV (NA PRIMERU KRASA, JZ SLOVENIJA) NATAŠA RAVBAR1 1 Karst Research Institute, SRC SASA, Titov trg 2, SI-6230 Postojna, Slovenia e-mail: [email protected] Prejeto / received: 23. 9. 2003 Acta carsologica, 33/1 (2004) Abstract UDC: 628,1;551.44(487.4) Nataša Ravbar: Drinking water supply from karst water resources (The example of the Kras plateau, SW Slovenia) In the past the biggest economic problem on the Kras plateau used to be drinking water supply, which has also been one of the reasons for sparsely populated Kras plateau. Today the Water Supply Company provides drinking water to households and industry on the Kras plateau and the quantity is suffi cient to supply the coastal region in the summer months as well. Water supply is founded on effective karst groundwater pumping near Klariči. Some water is captured from karst springs under Nanos Mountain as well. In water supply planning in future, numerous other local water resources linked to traditional ways of water supply need to be considered. Eventual rainwater usage for garden irrigation or car washing, for communal activity (street washing) or for the needs of farming and purifi ed wastewater usage for industry (as technologi- cal water) is not excluded. Key words: karst waters, human impact, drinking water supply, Klariči water resource, Kras plateau. Izvleček UDK: 628,1;551.44(487.4) Nataša Ravbar: Oskrba s pitno vodo iz kraških vodnih virov (na primeru Krasa, JZ Slovenija) Na Krasu je bil od nekdaj največji problem oskrba s kakovostno pitno vodo, ki je omejevala poselitev in gos- podarski razvoj območja. -

Župnija Tomaj 5

Župnija Tomaj 5. junij 2016 diplomsko delo z naslovom Albin Kjuder in Tomajska Ivan Tavčar: Albin Kjuder tomajski knjižnica. Od leta 1993 je zaposlen v sežanski Kosovelovi Kaj praznujemo? Primož Škabar: Tomajska knjižnica knjižnici kot vodja oddelka za nabavo. Koliko poznamo svoj kraj in župnijo? Koliko vemo o njeni zgodovini in vlogi na Krasu? Kulturni dom Tomaj, ob 19h Primož Škabar je eden najboljših poznavalcev Tomajske S katerimi zakladi se ponaša Tomaj? knjižnice. Kot študent bibliotekarstva jo je temeljito pregledal, Ali poznamo kakšno vidnejšo osebnost iz zgodovine, ki Ivan Tavčar se je rodil v Trstu, 21. aprila 1943. Tam je popisal in jo prikazal v diplomskem delu. Ker se je o vsebini je vplivala na razvoj našega kraja in naših prednikov? obiskoval je slovenske šole vse do diplome (Trgovski Tehnični knjižnice marsikaj domnevalo in govorilo, bomo tokrat lahko Zavod). Delal je kot špediterski izvedenec in prokurist, sedaj dejansko izvedeli, kaj se v njej nahaja in kako je bila urejena. 22. maj 2016 pa je v pokoju. Morda bomo potem še bolj cenili njen kulturni pomen za Duhovnik in pesnik Albert Miklavec Tomaj in širšo regijo ter spoznali pomemben del Kjudrovega Tržaški Slovenec, pesnik, pisatelj, muzikolog, ki je po krvi in po dela. Kulturni dom Tomaj, ob 19h kulturni umeščenosti pesnik treh jezikov in kultur: slovenske, italijanske in avstronemške. Že s tem dejstvom je najbolj značilen pesnik Trsta kot srednjeevropskega mesta. Italijanski Miroslava Cencič (Žvabova) je upokojena docentka za didaktiko, doktor pedagogike, zaslužna profesorica literarni kritiki ga imajo tudi za najbolj izrazitega tržaškega Univerze na Primorskem. Ukvarjala se je s teorijo vzgoje, z pesnika, tako po kulturni širini kot po izvirni poetiki. -

Seznam Naselij, Za Katera Ni Naložena Obveznost Cenovnega Nadzora in Stroškovnega Računovodstva

Priloga V spodnji tabeli se nahaja seznam naselij, za katera ni naložena obveznost cenovnega nadzora in stroškovnega računovodstva. Zap.št. Občina Naselje Na_mid 1 Beltinci Lipa 10116180 2 Cerklje na Gorenjskem Cerklje na Gorenjskem 10102553 3 Cerklje na Gorenjskem Češnjevek 10102588 4 Cerklje na Gorenjskem Dvorje 10102596 5 Cerklje na Gorenjskem Pšenična Polica 10103177 6 Cerklje na Gorenjskem Zgornji Brnik 10103673 7 Dolenjske Toplice Gabrje pri Soteski 10119227 8 Dolenjske Toplice Gorenje Polje 10119430 9 Dolenjske Toplice Mali Rigelj 10120314 10 Dolenjske Toplice Selišče 10121078 11 Dravograd Dravograd 10092396 12 Duplek Dvorjane 10147476 13 Duplek Spodnji Duplek 10148073 14 Gorenja vas-Poljane Gorenje Brdo 10136806 15 Gorenja vas-Poljane Jazbine 10136962 16 Gorenja vas-Poljane Lučine 10137217 17 Gorenja vas-Poljane Smoldno 10137683 18 Gorenja vas-Poljane Zakobiljek 10138159 19 Gorenja vas-Poljane Žirovski Vrh Sv. Urbana 10138299 Stegne 7, p.p. 418, 1001 Ljubljana, telefon: 01 583 63 00, faks: 01 511 11 01, e-naslov: [email protected], www.akos-rs.si, davčna št.:10482369 -1 Dopis SLO Stran 1 od 8 Zap.št. Občina Naselje Na_mid 20 Hoče-Slivnica Hotinja vas 10147522 21 Hoče-Slivnica Orehova vas 10147786 22 Hoče-Slivnica Radizel 10147913 23 Hoče-Slivnica Slivnica pri Mariboru 10148014 24 Hrpelje-Kozina Ocizla 10131456 25 Hrpelje-Kozina Prešnica 10131685 26 Hrpelje-Kozina Rodik 10131758 27 Hrpelje-Kozina Tublje pri Hrpeljah 10132096 28 Hrpelje-Kozina Vrhpolje 10132266 29 Ilirska Bistrica Dobropolje 10096979 30 Ilirska Bistrica Dolnji Zemon 10097002 31 Ilirska Bistrica Gornji Zemon 10097053 32 Ilirska Bistrica Ilirska Bistrica 10097096 33 Ilirska Bistrica Jablanica 10097100 34 Ilirska Bistrica Koseze 10097185 35 Ilirska Bistrica Pavlica 10097266 36 Ilirska Bistrica Topolc 10097517 37 Ilirska Bistrica Velika Bukovica 10097533 38 Ilirska Bistrica Vrbica 10097550 39 Ilirska Bistrica Vrbovo 10097568 40 Jesenice Jesenice 10097827 41 Jesenice Slovenski Javornik 17357808 -1 Dopis SLO Stran 2 od 8 Zap.št. -

Prikaz Stanja Prostora Občine Sežana

NAROČNIK OBČINA SEŽANA Partizanska cesta 4 I 6210 SEŽANA OBČINSKI PROSTORSKI NAČRT OBČINE SEŽANA PRIKAZ STANJA PROSTORA OBČINE SEŽANA IZVAJALEC LOCUS prostorske informacijske rešitve d.o.o. Ljubljanska cesta 76 I 1230 Domžale Domžale, januar 2016 PROJEKT PRIKAZ STANJA PROSTORA FAZA SPREJETO VSEBINA PROJEKTA PRIKAZ STANJA PROSTORA NAROČNIK OBČINA SEŽANA Partizanska cesta 4 6210 SEŽANA ŠTEVILKA PROJEKTA 404 IZDELOVALEC Locus d.o.o., Ljubljanska cesta 76, 1230 Domžale VODJA PROJEKTA Manca Jug, univ.dipl.inž.arh. ZAPS A 1302 STROKOVNA SKUPINA Leon Kobetič, univ.dipl.inž.grad. Tomaž Kmet, univ.dipl.inž.arh. Nuša Britovšek, univ.dipl.inž.kraj. arh. Metka Jug, univ.dipl.inž.kraj. arh. Jasmina Puškar, dipl.inž.graf.teh. Andrej Podjed, gr.teh. DATUM Domžale, januar 2016 Prikaz stanja prostora Kazalo 1 OSNOVNI PODATKI ZA OBMOČJE PROSTORSKEGA AKTA............................................................................... 9 2 BILANCA POVRŠIN ZEMLJIŠČ OSNOVNE NAMENSKE IN DEJANSKE RABE ..................................................... 10 3 BILANCA POVRŠIN OBMOČIJ POD RAZLIČNIMI VARSTVENIMI REŽIMI ......................................................... 13 3.1 Bilanca varstvenih območij – prostorski akti: .................................................................................................. 13 3.2 Bilanca varstvenih območij - kulturne dediščine ............................................................................................. 13 3.3 Bilanca varstvenih območij – naravne vrednote: ........................................................................................... -

Directions in Modeling Land Registration and Cadastre Domain – Aspects of EULIS Glossary Approach, Semantics and Information Services

Directions in modeling Land Registration and Cadastre Domain – Aspects of EULIS glossary approach, semantics and information services Esa TIAINEN, Finland Key words: property information, land register, cadastre, semantics, harmonization, standardization, modeling, terminology, ontology SUMMARY Experiences and lessons from the EULIS Project show that semantic modeling or standardization in land register and cadastral domain is possible to and should be based on real world functions. For carrying this through focus should be shifted more on services representing the real world context, instead of information contents and systems that only reflect the real world. Ontology explication and semantic translators can be used as surrogates to connect the existing systems to the ICT infrastructure related. A roadmap to this with quality assurance by quality labeling has been outlined, detailing the harmonization-standardization process. The structuring process is naturalistic aiming to ‘common sense’ terms in terminology standardization and by measuring the quality against user needs, and maybe slightly heuristic searching for most likely choices of the information community. As for cadastre, it may be stated that the legal aspects make up the 5th dimension in the information system domain. Another initiative for cadastral domain, and EULIS, is mapping the trustworthiness and matching the criteria for quality certification labels as detailed. RESUMÉ Les expériences du projet d'EULIS prouvent que modeler sémantique ou étalonnage le domaine cadastral est possible à et devrait être basé sur de vraies fonctions du monde. Pour accomplir ceci le foyer devrait être décalé plus aux services représentant le vrai contexte du monde, au lieu du contenu de l'information et des systèmes seulement reflétant le vrai monde.