Eustathius of Antioch in Modern Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lara O'sullivan, Fighting with the Gods

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT: 2014 NUMBERS 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson ò David Hollander ò Timothy Howe Joseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel ò Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 28 (2014) Numbers 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume twenty-eight Numbers 3-4 82 Lara O’Sullivan, Fighting with the Gods: Divine Narratives and the Siege of Rhodes 99 Michael Champion, The Siege of Rhodes and the Ethics of War 112 Alexander K. Nefedkin, Once More on the Origin of Scythed Chariot 119 David Lunt, The Thrill of Victory and the Avoidance of Defeat: Alexander as a Sponsor of Athletic Contests NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Greetings and Thanksgiving the Salutation

Thessalonians 1 & 2 1 Thessalonian 1: Greetings and Thanksgiving The Salutation The salutation names three authors of the letter, Paul, Silvanus, also known by his nickname Silas, and Timothy. Both of Paul’s fellow workers played important roles in the development of his missionary activity. According to Acts 15:22, Silas was part of the delegation sent to Antioch to announce the results of the “apostolic council” in Jerusalem. Paul chose him as a companion in his missionary activity in Syria and Cilicia, his “first missionary journey” (Acts 15:40). It was during that journey, in Derbe and Lystra, where Paul encountered Timothy, son of a Jewish mother and Greek father (Acts 16:1), whom he recruited to his missionary team. Silas continued with Paul and was with him in prison in Philippi (Acts 16:19–40), and he was with Paul when the apostle initially worked in Thessalonica (Acts 17:4-9) and Beroea (Acts 17:10). Timothy apparently was part of the team as well, since he remained with Silas in Beroea when Paul was sent off (Acts 17:14). Silas and Timothy reunited with Paul in Athens (Acts 18:5), which was probably the location from which Paul sent Timothy on the mission to Thessalonica, a mission to which he refers later in 1 Thess 3:2. If the account in Acts is correct, Silas accompanied Timothy on the trip; and the two rejoined Paul in Corinth (Acts 18:5), providing the occasion for writing the letter. The presence of Silas and Timothy with Paul in Corinth when he first preached there is confirmed by Paul’s reminiscence of the start of his mission there in 2 Corinthians 1:19. -

Background for the Bible Passage Session !: God in Culture

BACKGROUND FOR THE BIBLE PASSAGE SESSION !: GOD IN CULTURE Life Question: How can I use culture to express my who, no doubt, lifted him up mightily in prayer would be an faith? encouragement to him as he faced an entirely new experience Biblical Truth: We can start where people are in their in Athens. cultures to explain to them the message Certainly Paul had heard much about Athens previously, but of Christ. we can only imagine that he was ill-prepared for what he found Focal Passage: Acts 17:16-34 as he entered the city through one of its massive gates. The wall surrounding Athens had a circumference of 5 to 6 miles. Most likely Paul was awed by architecture that greeted him, with the Ben Feldman moved to Central City High School when he was grandeur of this center of Greek culture. If Paul had entered the a junior. His father, a prominent neurosurgeon, had joined the city through one of the northeast gates, he probably saw first medical faculty at Central City’s large teaching hospital. The the Hephaesteum, a beautiful Doric temple built between 449- family had moved from upstate New York to the deep South, 444 B.C. and dedicated to the god Hephaestus and the goddess and more specifically to the Bible Belt. Ben’s family came from Athena. Across from the Hephaesteum was the Stoa of Attalus, an entirely different culture in which “religion” was little more a two-storied, colonnaded building which was given to Athens than a traditional heritage. Ben was a brilliant student who around A.D. -

Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian

Epidamnus S tr Byzantium ym THRACE on R Amphipolis A . NI PROPONTIS O Eion ED Thasos Cyzicus C Stagira Aegospotami A Acanthus CHALCIDICE M Lampsacus Dascylium Potidaea Cynossema Scione Troy AEOLIS LY Corcyra SA ES Ambracia H Lesbos T AEGEAN MYSIA AE SEA Anactorium TO Mytilene Sollium L Euboea Arginusae Islands L ACAR- IA YD Delphi IA NANIA Delium Sardes PHOCISThebes Chios Naupactus Gulf Oropus Erythrae of Corinth IONIA Plataea Decelea Chios Notium E ACHAEA Megara L A Athens I R Samos Ephesus Zacynthus S C Corinth Piraeus ATTICA A Argos Icaria Olympia D Laureum I Epidaurus Miletus A Aegina Messene Delos MESSENIA LACONIA Halicarnassus Pylos Sparta Melos Cythera Rhodes 100 miles 160 km Crete Map 1 Greece. xvii W h i t 50 km e D r i n I R. D rin L P A E O L N IA Y Bylazora R . B S la t R r c R y k A . m D I A ) o r x i N a ius n I n n ( Epidamnus O r V e ar G C d ( a A r A n ) L o ig Lychnidus E r E P .E . R o (Ochrid) R rd a ic s u Heraclea u s r ) ( S o s D Lyncestis d u U e c ev i oll) Pella h l Antipatria C c l Edessa a Amphipolis S YN E TI L . G (Berat) E ( AR R DASS Celetrum Mieza Koritsa E O O R Beroea R.Ao R D Aegae (Vergina) us E A S E on Methone T m I A c Olynthus S lia Pydna a A Thermaic . -

14 Days at Your Local Passport Office

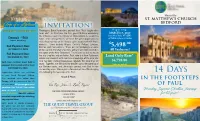

Hosted By: JOIN US YOUR ST. MATTHEW’S CHURCH for a BEDFORD Trip of a Lifetime INVITATION! Departing: IMPORTANT INFORMATION Theologian, Ernst Kasemann, posited that: “Paul taught what Jesus did.” St. Paul was the first great Christian missionary. MARCH 15, 2020 from New York, NY (JFK) $ His influence upon the history of Christendom is second to Deposit - 500 none. This coming March, we have the great opportunity to on Turkish Airlines or similar (upon booking) visit a large number of the historic sights associated with Paul’s ministry. Stops include Athens, Corinth, Philippi, Ephesus, $ .00 2nd Payment Due: Patmos, and many others. These are the birthplaces of some 5,498 OCTOBER 17, 2019 of the earliest Christian churches, and are well documented in All Inclusive! the pages of the New Testament. The trip will be led by me, as Full Payment Due: the trip chaplain, and my father, Paul, who is a New Testament Land Only Rate* DECEMBER 31, 2019 scholar and classicist with extensive knowledge of the area, and who has been visiting these places regularly for more than 40 $4,798.00 Each tour member must hold a years. Together, we will certainly deepen our understanding of passport that is valid until at least *Airfare not included our Christian roots, and, ultimately, connect with God in new OCTOBER 15, 2020. and exciting ways. Please join us for what will be a life-changing Application forms are available trip, following the footsteps of St. Paul. 14 Days at your local Passport Office. Grace & Peace, Any required visas other than IN THE FOOTSTEPS Turkey, will be processed for US citizens only. -

Archaeology and the Book of Acts

Criswell Theological Review 5.1 (1990) 69-82. Copyright © 1990 by The Criswell College. Cited with permission. ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE BOOK OF ACTS JOHN MCRAY Wheaton College Graduate School, Wheaton, IL 60187 The winds of biblical scholarship have blown toward the Book of Acts from a largely theological direction for the past quarter of a century,1 providing a corrective to the pervasive concern with ques- tions of historicity fostered by the work of W. Ramsay almost a century ago.2 However, the winds are changing again, and interest is once more being kindled in questions relating to the trustworthiness of Acts. These changing winds are blowing from such unlikely places as the University of Tubingen itself, whose extremely critical views were held by Ram- say prior to his sojourn in Asia Minor. For example, M. Hengel, a NT scholar at Tubingen, "makes a bold departure from radical NT scholar- ship in supporting the historical integrity of the Acts of the Apostles. and demonstrates that Luke's account is historically reliable. ."3 Miti- gating cases against the hyperskepticism of scholars like J. Knox,4 and G. Leudemann,5 are now being made in various quarters bolstered by new discoveries in archaeological and inscriptional material.6 1 C. Talbert, ed., Perspectives on Luke-Acts (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1978); I. H. Marshall, Luke: Historian and Theologian (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1970); L. E. Keckand J. L. Martyn, Studies in Luke-Acts (Nashville: Abingdon, 1966). 2 W. Ramsay, St. Paul the Traveller and Roman Citizen (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1908); idem, The Cities of St. -

The Pillar New Testament Commentary General Editor D. A. CARSON

The Pillar New Testament Commentary General Editor D. A. CARSON The Letters to the THESSALONIANS GENE L. GREEN William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company Grand Rapids, Michigan / Cambridge, U.K. Color profile: Disabled Composite 140 lpi at 45 degrees ©2002Wm.B.EerdmansPublishingCo. 2140 Oak Industrial Drive N.E., Grand Rapids, Michigan 49505 / P.O. Box 163, Cambridge CB3 9PU U.K. All rights reserved www.eerdmans.com First published 2002 in the United States of America by Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. and in the United Kingdom by APOLLOS 38 De Montfort Street, Leicester, England LE1 7GP Printed in the United States of America 14 13 12 11 10 09 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Green, Gene L. The letters to the Thessalonians / Gene L. Green. p. cm. (The Pillar New Testament commentary) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8028-3738-7 (alk. paper) 1. Bible. N.T. Thessalonians — Commentaries. I. Title. II. Series. BS2725.53.G74 2002 227¢.81077 — dc21 2002019444 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary. Scripture taken from the HOLY BIBLE: NEW INTERNATIONAL VERSION®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan Publishing House. Green, Pillar Thessalonians 3rd printing Wednesday, January 07, 2009 8:56:54 AM 4 ADeborah mi corazón y aGillianyChristiana mi sangre Contents Series Preface xi Author’s Preface xiii Abbreviations xvi Bibliography xix INTRODUCTION I.RIVERS, ROADS, ROLLING MOUNTAINS, AND THESEA: GEOGRAPHY AND TRAVEL THROUGH MACEDONIAANDTHESSALONICA 1 II.ASUMMARYHISTORY OFMACEDONIAAND THESSALONICA 8 III. THEGOVERNMENT OFTHESSALONICA 20 IV. -

Handout: 1 Corinthians Lesson 1

Handout: 1 Corinthians Lesson 1 SUMMARY OUTLINE OF FIRST CORINTHIANS Biblical Period #12: The Messianic Age of the Church of Jesus Christ Covenant The New Covenant in Christ Jesus Focus Introduction and Answering the Correcting Problems Addressing the Community’s in Liturgical Community’s Problems Questions Worship/Doctrine Conclusion Scripture 1:1-----1:9---------------------7:1----------------8:1-----------11:2--------------16:1---16:24 Greeting, Divisions and Marriage Offerings Modest attire, Conclu- Division blessing, moral disorders and celibacy to idols Communion, sion thanks- spiritual gifts, giving resurrection Factions and scandals Sexual immorality and Right Alms for Topic pagan practices worship Jeru- salem Paul’s letter is written from the Roman city of Ephesus in Asia Minor Location to the Christian community in the Roman city of Corinth, capital of the Roman Province of Achaea (Greece) Time Sometime between 55-57 AD Michal E. Hunt Copyright © 2017 I. Introduction and Answering the Community’s Problems (1:1-20) A. Greeting B. Divisions and moral disorders II. Answering to the Corinthians’ Questions (7:1-11:1) A. Marriage and Celibacy B. Offerings to Idols IV. Problems in the Liturgy of Worship/Doctrine and Conclusion (11:2-16:24) A. Modest attire B. Communion C. Spiritual Gifts D. Resurrection 1. Resurrection of Christ 2. Resurrection of the Dead 3. Manner of the Resurrection E. Conclusion over THE LIFE OF PAUL: “Apostle to the Goyim (Gentiles)” EVENT YEAR AD (all dates are approximate) Born at Tarsus (in modern Turkey) -

Big Classical Tour of Greece

Big Classical Tour of Greece Tour Itinerary DAY 1 - Athens - Corinth Canal - Nauplion - Mycenae - Tripolis - Megalopolis - Olympia - (D) Leave by the coastal road to the Corinth Canal (short stop). Drive on and visit the Theatre of Epidauros famous for its remarkable acoustics. Then proceed to the Town of Nauplion (short stop) drive on to Mycenae and visit the Archaeological Site and the Tomb of Agamemnon. Then depart for Olympia through Central Peloponnese and the Towns of Tripolis and Megalopolis. Overnight in Olympia, the cradle of the Olympic Games. (Dinner) DAY 2 - Olympia - Ilia – Achaia - Corinthian Bay - Nafpactos (Lepanto) - Itea – Delphi - (D) In the morning visit the Archaeological Site with the sanctuary of Olympian Zeus, the Ancient Stadium and the archaeological Museum. Then drive on through the plains of Ilia and Achaia until the magnificent bridge which is crossing the Corinthian Bay from Rion to Antirion. Pass by the picturesque Towns of Nafpactos (Lepanto) and Itea, arrive in Delphi. Overnight. (Dinner) DAY 3 - Delphi - Kalambaka - (D) In the morning visit the archaeological Site and the Museum of Delphi. Depart for Kalambaka, a small Town situated at the foot of the astonishing complex of Meteora, gigantic rocks. Overnight. (Dinner) DAY 4 - Meteora (Kalambaka) - Thessaly - Dion - Mount Olympos - Thessaloniki - (D) Visit Meteora, among striking scenery, perched on the top of huge rocks which seem to be suspended in mid-air, stand ageless Monasteries, where you can see exquisite specimens of Byzantine art. Depart from Kalambaka, drive through the plain of Thessaly and the valley of Tempi, arrive and visit the Archaeological Park of Dion. -

III. Roman Macedonia (168 BC - AD 284)

III. Roman Macedonia (168 BC - AD 284) by Pandelis Nigdelis 1. Political and administrative developments 1.1. Macedonia as a Roman protectorate (168–148 BC) A few months after defeating Perseus, the last king of Macedonia, at Pydna (168 BC) the Romans found themselves facing the crucial question of how to govern the country. The question was not a new one. It had arisen thirty years before, after their victory over Perseus’ father, Philip V, at Cynoscephalae (197 BC), when the solution adopted was to preserve the kingdom within its old historical boundaries and to have the heir to the throne, Demetrius, educated in Rome, so that Macedonia would continue to fulfil its vital role as a rampart defending southern Greece against barbarian invasion. The latest war had shown that this solution was unrealistic, and that harsher measures were re- quired for more effective control over the land. The Romans still, however, avoided becoming directly involved in the government of the country, for they did not want to assume responsibility for its defence. They therefore, having set the amount of the an- nual taxation at 100 talents, or half its previous level (an unavoidable reduction given that they were abolishing some of the revenues enjoyed by the previous regime), and collected spoils and plunder worth a total of 6000 talents, opted for the solution of a Macedonia politically divided and economically enfeebled. The political fragmentation of Macedonia was achieved primarily by the creation of four self-governing “cantons” (regiones); these, with the exception of Paeonia (which, although inhabited by a single tribe, was divided under the new system), were defined on the basis of their historical boundaries. -

BEGINNINGS Ad 1–325 SUMMARY Christianity Rapidly Spread Beyond Its Original Geographical Region of Roman-Occupied Palestine Into the Entire Mediterranean Area

PART 1 BEGINNINGS AD 1–325 SUMMARY Christianity rapidly spread beyond its original geographical region of Roman-occupied Palestine into the entire Mediterranean area. Something of this process of expansion is described in the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament. It is clear that a Christian presence was already established in Rome itself within fifteen years of the resurrection of Christ. The imperial trade routes made possible the rapid traffic of ideas, as much as merchandise. Three centers of the Christian church rapidly emerged in the eastern Mediterranean region. The church became a significant presence in its own original heartlands, with Jerusalem emerging as a leading center of thought and activity. Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) was already an important area of Christian expansion, as can be seen from the destinations of some of the apostle Paul’s letters, and the references to the ‘seven churches of Asia’ in the book of Revelation. The process of expansion in this region continued, with the great imperial city of Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) becoming a particularly influential center of mission and political consolidation. Yet further growth took place to the south, with the important Egyptian city of Alexandria emerging as a stronghold of Christian faith. With this expansion, new debates opened up. While the New Testament deals with the issue of the relationship of Christianity and Judaism, the expansion of Christianity into Greek-speaking regions led to the exploration of the way in which Christianity related to Greek philosophy. Many Christian writers sought to demonstrate, for example, that Christianity brought to fulfilment the great themes of the philosophy of Plato. -

The Location of the Trout-River Astraeus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1995; 36, 2; Proquest Pg

The location of the trout-river Astraeus Hammond, N G L Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1995; 36, 2; ProQuest pg. 173 The Location of the Trout-River Astraeus N. G. L. Hammond LIAN informs us that fishermen used a rod (KaAallo~) and a line (oPllta), each about six feet long, and an artificial fly J\to catch "fishes of a speckled hue" in a river called Astraeus in Macedonia (NA 15.1). The method and the descrip tion indicate that the fish were trout. Ae1ian presumably chose to name the Astraeus as the river most famous for its trout, because we cannot suppose that it was unique among Mace donian rivers in harbouring trout. The only clue to the position of the river which Aelian gives us is that it lay "between Beroea and Thessalonica." Can we get any closer? Leake took us farther afield in sug gesting that" Astraeus" was another name for the Haliacmon;l but that river did not flow between Beroea and Thessalonica. The Loeb editor of the passage in Aelian makes the comment, "presumably the Axius is intended";2 but surely Aelian knew the Axius under its given name. We need rather to note that there was a nymph Astraea, appropriate to a river of her name, " Astraeus," and that she was selected as the nurse of the lady Beroe (Nonnus Dion. 41.212f), the patroness of Beroea (the city was sometimes called Beroe). We conclude that the Astraeus was near Beroea and that it flowed on the Thessalonica side of Beroea. The eastern neighbour of the Astraeus was the Ludias, which rose in Almopia, flowed through the Almopian city Europus and in the time of Herodotus flowed into the Haliac mon, but later its waters joined those of the Axius to form Lake Ludias by Pella.