Chapter Four: a Contest for Souls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acrocephalus, 2010, Letnik 31, Številka

Acrocephalus 31 (147): 175−179, 2010 A Milestone on the Road to Natura 2000 Mejnik na poti k Naturi 2000 The publication “Important Bird Areas of Macedonia: Sites of Global and European Importance” provides a fascinating insight into the natural and cultural heritage of the country. The approved list of sites now includes a wide variety of landscapes hosting bird species that have become rare or threatened in many parts of Europe. Very important is the fact that only about 21% of the national protected area network overlaps the Important Bird Areas of Macedonia. Now an assessment of the natural assets of Macedonia is available for the first time, based on a systematic approach using the international criteria developed by BirdLife International for the selection of sites under the EU Birds Directive. The first results indicate where the country hosts areas of European and even global importance, where urgent conservation measures are needed, and are excellent guidelines for the rural development and tourism. A wide range of political commitments within the European Union is aimed at preserving ecosystems and biodiversity, with various species protection provisions as well as Special Protection Areas (SPAs) identified under the Birds Directive and Sites of Community Importance (SCIs) identified under the Habitats Directive, both incorporated into the Natura 2000 (N2000) network. The publication of the “Important Bird Areas of Macedonia” prepared by the Macedonian Ecological Society (MES) as a national representative of the BirdLife International’s partnership is the first systematic assessment of Macedonia’s sites based on the internationally recognized criteria to implement the Birds Directive. -

Monitoring Methodology and Protocols for 20 Habitats, 20 Species and 20 Birds

1 Finnish Environment Institute SYKE, Finland Monitoring methodology and protocols for 20 habitats, 20 species and 20 birds Twinning Project MK 13 IPA EN 02 17 Strengthening the capacities for effective implementation of the acquis in the field of nature protection Report D 3.1. - 1. 7.11.2019 Funded by the European Union The Ministry of Environment and Physical Planning, Department of Nature, Republic of North Macedonia Metsähallitus (Parks and Wildlife Finland), Finland The State Service for Protected Areas (SSPA), Lithuania 2 This project is funded by the European Union This document has been produced with the financial support of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the Twinning Project MK 13 IPA EN 02 17 and and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 6 Summary 6 Overview 8 Establishment of Natura 2000 network and the process of site selection .............................................................. 9 Preparation of reference lists for the species and habitats ..................................................................................... 9 Needs for data .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Protocols for the monitoring of birds .................................................................................................................... -

The Aromanians in Macedonia

Macedonian Historical Review 3 (2012) Македонска историска ревија 3 (2012) EDITORIAL BOARD: Boban PETROVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editor-in-chief) Nikola ŽEŽOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Dalibor JOVANOVSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Toni FILIPOSKI, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia Charles INGRAO, Purdue University, USA Bojan BALKOVEC, University of Ljubljana,Slovenia Aleksander NIKOLOV, University of Sofia, Bulgaria Đorđe BUBALO, University of Belgrade, Serbia Ivan BALTA, University of Osijek, Croatia Adrian PAPAIANI, University of Elbasan, Albania Oliver SCHMITT, University of Vienna, Austria Nikola MINOV, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Macedonia (editorial board secretary) ISSN: 1857-7032 © 2012 Faculty of Philosophy, University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius, Skopje, Macedonia University of Ss. Cyril and Methodius - Skopje Faculty of Philosophy Macedonian Historical Review vol. 3 2012 Please send all articles, notes, documents and enquiries to: Macedonian Historical Review Department of History Faculty of Philosophy Bul. Krste Misirkov bb 1000 Skopje Republic of Macedonia http://mhr.fzf.ukim.edu.mk/ [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 Nathalie DEL SOCORRO Archaic Funerary Rites in Ancient Macedonia: contribution of old excavations to present-day researches 15 Wouter VANACKER Indigenous Insurgence in the Central Balkan during the Principate 41 Valerie C. COOPER Archeological Evidence of Religious Syncretism in Thasos, Greece during the Early Christian Period 65 Diego PEIRANO Some Observations about the Form and Settings of the Basilica of Bargala 85 Denitsa PETROVA La conquête ottomane dans les Balkans, reflétée dans quelques chroniques courtes 95 Elica MANEVA Archaeology, Ethnology, or History? Vodoča Necropolis, Graves 427a and 427, the First Half of the 19th c. -

P R O C E E D I N G S

GOCE DELCEV UNIVERSITY OF STIP FACULTY OF TOURISM AND BUSINESS LOGISTICS FACULTY OF TOURISM P R O C E E D I N G S THE 2 ND INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE CHALLENGES OF TOURISM AND BUSINESS LOGISTICS IN T H E 2 1 ST CENTURY S tip, September 13 th, 2 0 1 9 North Macedonia Publisher: Faculty of Tourism and Business logistics Goce Delcev University of Stip “Krste Misirkov” no.10-A P.O. Box 201 Stip 2000, North Macedonia Tel: +389 32 550 350 www.ftbl.ugd.edu.mk www.ugd.edu.mk For the Publisher: Nikola V. Dimitrov, Ph.D. – Dean Technical Support Cvetanka Ristova, M.Sc., University Teaching Assistant, Goce Delcev University of Stip, Faculty of Tourism and Business logistics, Stip, North Macedonia Conference organizer Goce Delcev University of Stip, Faculty of Tourism and Business logistics Co-organizers: - St. Clement of Ohrid University of Bitola, Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality, Ohrid, North Macedonia - University of Kragujevac, Faculty of Hotel Management and Tourism in Vrnjačka Banja, Serbia - St. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje, Institute of Geography, Faculty of Natural Sciences and Mathematics, Skopje, North Macedonia - Konstantin Preslavsky University of Shumen, Faculty of Natural Sciences, Department of Geography, regional development and tourism, Shumen, Bulgaria - University Haxhi Zeka, Faculty of Management in Tourism, Hotels and the Environment, Peć, Kosovo - Singidunum University, Faculty of Applied Ecology Futura, Belgrade, Serbia - Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Thessaloniki, Greece CIP - Каталогизација во публикација Национална и универзитетска библиотека Св. „Климент Охридски“, Скопје 338.48(062) INTERNATIONAL scientific conference "Challenges of tourism and business logistics in the 21st century, ISCTBL (2 ; 2019 ; Stip) Proceedings / Second international scientific conference "Challenges of tourism and business logistics in 21st century, ISCTBL, Stip, September 13th, 2019. -

On the Basis of Article 65 of the Law on Real Estate Cadastre („Official Gazette of Republic of Macedonia”, No

On the basis of article 65 of the Law on Real Estate Cadastre („Official Gazette of Republic of Macedonia”, no. 55/13), the Steering Board of the Agency for Real Estate Cadastre has enacted REGULATION FOR THE MANNER OF CHANGING THE BOUNDARIES OF THE CADASTRE MUNICIPALITIES AND FOR DETERMINING THE CADASTRE MUNICIPALITIES WHICH ARE MAINTAINED IN THE CENTER FOR REC SKOPJE AND THE SECTORS FOR REAL ESTATE CADASTRE IN REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA Article 1 This Regulation hereby prescribes the manner of changing the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities, as well as the determining of the cadastre municipalities which are maintained in the Center for Real Estate Cadastre – Skopje and the Sectors for Real Estate Cadastre in Republic of Macedonia. Article 2 (1) For the purpose of changing the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities, the Government of Republic of Macedonia shall enact a decision. (2) The decision stipulated in paragraph (1) of this article shall be enacted by the Government of Republic of Macedonia at the proposal of the Agency for Real Estate Cadastre (hereinafter referred to as: „„the Agency„„). (3) The Agency is to submit the proposal stipulated in paragraph (2) of this article along with a geodetic report for survey of the boundary line, produced under ex officio procedure by experts employed at the Agency. Article 3 (1) The Agency is to submit a proposal decision for changing the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities in cases when, under a procedure of ex officio, it is identified that the actual condition/status of the boundaries of the cadastre municipalities is changed and does not comply with the boundaries drawn on the cadastre maps. -

Macedonian Post» – Skopje MKA MK

Parcel Post Compendium Online MK - Republic of North Macedonia State-owned joint stock company for postal traffic MKA «Macedonian Post» – Skopje Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination No 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 30 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 30 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are No registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence -

Trajan Belev-Goce

Trajan Belev – Goce By Gjorgi Dimovski-Colev Translated by Elizabeth Kolupacev Stewart 1 The Historical Archive – Bitola and the Municipal Council SZBNOV – Bitola “Unforgotten” Editions By Gjorgi Dimovski–Colev Trajan Belev – Goce Publisher board Vasko Dimovski Tode Gjoreski vice president Zlate Gjorshevski Jovan Kochankovski Aleksandar Krstevski Gjorgji Lumburovski (Master) Cane Pavlovski president Jovo Prijevik Kiril Siljanovski Ilche Stojanovski Gjorgji Tankovski Jordan Trpkovski Editorial Board Stevo Gadzhovski Vasko Dimovski Tode Gjoreski Master Gjorgji Lumburovski chief editor Jovan Kochanovski Aleksandar Krstevski, alternate chief editor Gjorgji Tankovski Reviewers Dr Trajche Grujoski Dr Vlado Ivanovski 2 On the first edition of the series “The Unforgotten.” The history of our people and particularly our most recent history which is closely connected to the communist Party of Yugoslavia and SKOJ bursting with impressive stories of heroism, self-sacrifice, and many other noble human feats which our new generations must learn about. Among the precious example of political consciousness and sacrifice in the great and heroic struggle our future generations do not need to have regard to the distant past but can learn from the actions of youths involved in the living reality of the great liberation struggle. The publication of the series “Unforgotten” represents a program of the Municipal Council of the Union of the fighters of the NOB – Bitola. The series is comprised of many publications of famous people and events from the recent revolutionary past of Bitola and its environs. People who in the Liberation battle and the socialist revolution showed themselves to be heroes and their names and their achievements are celebrated in the “Unforgotten” series by the people. -

Heraclea, Pelagonia and Medieval Bitola: an Outline of the Ecclesiastical History (6Th-12Th Century)

Robert MIHAJLOVSKI Heraclea, Pelagonia and Medieval Bitola: An outline of the ecclesiastical history (6th-12th century) uDK 94:27(497.774)”5/l 1” La Trobe university, Melbourne [email protected] Abstract: Thisstudy presents my long-term field researCh on the Early Christian episCopal seat o f HeraClea LynCestis that was loCated along the anCient Roman Via Egnatia and in the valley o f Pelagonia. 1 disCuss various historiCal sourCes and topography of the region of medieval bishopric o f Pelagonia and Bitola. In addition, I also deal with the Christian Cultural heritage in the region. In this work these approaChes are within the Context o f archaeologiCal, historiCal and eCClesiastiCal investigation in the sites o f anCient HeaClea and modern Bitola. Key words: Heraclea Lyncestis, Pelagonia, Bitola, Prilep, Via Egnatia The Early Christian world on the Balkan Peninsula began to crumble already in the fourth century, with the invasions and migrations of the peoples and tribes. Vizigoths disrupted Balkan urban conditions in 378, the Huns of Atilla ravaged in 447 and Ostrogoths in 479. After the year 500 the disturbing catastrophes included an earthquake in 518, which seriously damaged the urban centers. Then came the Bubonic plague of 541-2, which was a terrible disaster of unprecedented magnitude, and other epidemics and catastrophes, which were recorded in 555, 558, 561, 573, 591 and 599.1 The invasions, epidemics and economic recession badly affected the population and society of the Eastern Roman Empire. Life in Herclea Lynkestis slowly declined. The Episcopal church was rebuilt in the early sixth century when the latest published coins of Justin II are found. -

Revitalization and Modernization of REK Bitola, III Phase- Reduction Of

Revitalization and Modernization of REK Bitola, III phase - Reduction of SOx and Dust Skopje, 2019 Introduction JSC ESM prepared a study for construction of desulfurization plant in cooperation with an external consultant within the period 2011 -2012. The study includes analysis of only one desulfurization technology, so called “wet method”, which represented the most conventional solution at the time. However, considering the high investment cost of the processed technology, as well as the fact that meanwhile two reference technologies (dry and semi-dry) have emerged on desulfurization technologies’ market, which is increasingly applied in the contemporary industry, JSC ESM in cooperation with Rudis, D.O.O. Trbovlje from Slovenia developed a new Feasibility Study in 2016. This study covered parameters related to the cost-effectiveness of the SOx and dust reduction procedure, including assessment of the impact of all harmful substances arising from the production process in TPP "Bitola". Project Description Comparative analysis of wet, dry and semi-dry methods of the applicable technologies for desulfurization in REK "Bitola" had been carried out in order to compare the techno-economic parameters, whereby world experience for all variants separately are taken into account. According to the results of the comparative analysis, the technology for desulfurization using the “wet method” is optimal and most appropriate for the existing technological process and equipment in operation in REK "Bitola". The study concerning the selected optimal technology for reducing emissions of SOx and dust during the operation of the three units in REK "Bitola, was prepared precisely to present a detailed analysis of the procedure itself. -

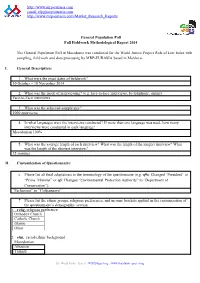

General Population Poll. Full Fieldwork Methodological Report

http://www.mrp-eurasia.com email: [email protected] http://www.mrp-eurasia.com/Market_Research_Reports General Population Poll Full Fieldwork Methodological Report 2014 The General Population Poll in Macedonia was conducted for the World Justice Project Rule of Law Index with sampling, fieldwork and data processing by MRP-EURASIA based in Moldova. I. General Description: 1. What were the exact dates of fieldwork? 10 October – 10 November 2014 2. What was the mode of interviewing? (e.g. face-to-face interviews, by telephone, online) Face-to-Face interviews 3. What was the achieved sample size? 1000 interviews 4. In what languages were the interviews conducted? If more than one language was used, how many interviews were conducted in each language? Macedonian 100% 5. What was the average length of each interview? What was the length of the longest interview? What was the length of the shortest interview? 32 minutes II. Customization of Questionnaire: 6. Please list all final adaptations to the terminology of the questionnaire (e.g. q9a: Changed “President” to “Prime Minister” or q3: Changed “Environmental Protection Authority” to “Department of Conservation”). “Parliament” to “Собранието” 7. Please list the ethnic groups, religious preferences, and income brackets applied in the customization of the questionnaire’s demographic section. 1. relig. religious preference Orthodox Church Catholic Church Islamic Other 2. etni. racial-ethnic background Macedonian Albanian Turkish The World Justice Project | [email protected] | www.worldjusticeproject.org http://www.mrp-eurasia.com email: [email protected] http://www.mrp-eurasia.com/Market_Research_Reports Roma Wallachia Serbian Bosniak Other 3. income. J Low household income Below 180 USD R below the average household income 180- 360 USD C Average household income 360-677 USD M above the average household income 677- 1355 USD F Highest household income above 1355 USD 8. -

Page 1 Adventure Experience Tour in N.Macedonia (Pelagonija / Prespa) and Greece (Prespes) Project: Increasing Tourism Opportuni

Adventure Experience Tour in N.Macedonia (Pelagonija / Prespa) and Greece (Prespes) Project: Increasing Tourism Opportunities through Utilization of Resources (I-Tour), Implemented by: Center for Development of the Pelagonija Planning Region- Bitola Activities: Multisport adventure combined with local cultural and gastronomy highlights Areas visited: Krushevo, Bitola, Demir Hisar, Pelister national park, Prespes national park, Florina Day 1 N. Macedonia / Tandem paragliding & Horse Riding in Krushevo 08:30-09:30 Welcome group briefing in Krusevo. 09:30-14:00 In recent years Krusevo has earned the reputation of one of Europe’s top tandem paragliding spots due to its high altitude and frequent thermals. The tandem paragliding flights in Krusevo are different than other locations in Macedonia because of the beautiful natural setting (flying over the forests and valleys instead of flying above urban area). The take-off spot is located in the historical area known as Gumenja, near the historical landmark “Meckin Kamen”, only a few kilometers from the center of Krusevo, while the landing spot is usually near the village of Krivogastani. This flight usually lasts for 20-25 minutes. But if the weather is good and guests are lucky to catch nice thermals, the instructor can offer them to stay up in the air for 20 minutes more and to land far away from the previously agreed landing place. There is available ground support team will pick the guests up from where they landed. There is also the option for extended flight for additional cost. Recommended clothing: Hiking boots with ankle support, as well as sunglasses. The paragliding equipment is provided by the tandem provider. -

Watershed, Macedonia

293 A summary of the environmental and socio-economic characteristics of the Crna Reka (Crna River) watershed, Macedonia Zoran Spirkovski Trajce Talevski Dusica Ilik-Boeva Goce Kostoski Odd Terje Sandlund NINA Publications NINA Report (NINA Rapport) This is a new, electronic series beginning in 2005, which replaces the earlier series NINA commis- sioned reports and NINA project reports. This will be NINA’s usual form of reporting completed re- search, monitoring or review work to clients. In addition, the series will include much of the insti- tute’s other reporting, for example from seminars and conferences, results of internal research and review work and literature studies, etc. NINA report may also be issued in a second language where appropriate. NINA Special Report (NINA Temahefte) As the name suggests, special reports deal with special subjects. Special reports are produced as required and the series ranges widely: from systematic identification keys to information on impor- tant problem areas in society. NINA special reports are usually given a popular scientific form with more weight on illustrations than a NINA report. NINA Factsheet (NINA Fakta) Factsheets have as their goal to make NINA’s research results quickly and easily accessible to the general public. The are sent to the press, civil society organisations, nature management at all lev- els, politicians, and other special interests. Fact sheets give a short presentation of some of our most important research themes. Other publishing In addition to reporting in NINA’s own series, the institute’s employees publish a large proportion of their scientific results in international journals, popular science books and magazines.