The on Theatre Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

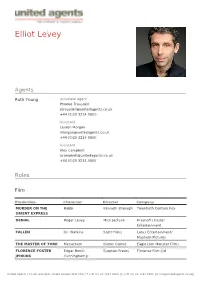

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017 Hosted by Elder Conservatorium of Music, The University of Adelaide. September 28th to October 1st, 2017 Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017, Adelaide, South Australia Keynote Speaker: Professor Takashi Ikegami Published by The Australasian University of Tokyo Computer Music Association Paper & Performances Jury: http://acma.asn.au Stephen Barrass September 2017 Warren Burt Paul Doornbusch ISSN 1448-7780 Luke Dollman Luke Harrald Christian Haines All copyright remains with the authors. Cat Hope Robert Sazdov Sebastian Tomczak Proceedings edited by Luke Harrald & Lindsay Vickery Barnabas Smith. Ian Whalley Stephen Whittington All correspondence with authors should be Organising Committee: sent directly to the authors. Stephen Whittington (chair) General correspondence for ACMA should Michael Ellingford be sent to [email protected] Christian Haines Luke Harrald Sue Hawksley The paper refereeing process is conducted Daniel Pitman according to the specifications of the Sebastian Tomczak Australian Government for the collection of Higher Education research data, and fully refereed papers therefore meet Concert / Technical Support Australian Government requirements for fully-refereed research papers. Daniel Pitman Michael Ellingford Martin Victory With special thanks to: Elder Conservatorium of Music; Elder Hall; Sud de Frank; & OzAsia Festival. DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF COMPUTER MUSIC? COMPUTER MUSIC IN THE AGE OF MACHINE -

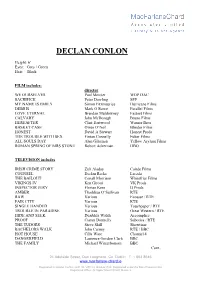

Declan Conlon

DECLAN CONLON Height: 6’ Eyes: Grey / Green Hair: Black FILM includes: director WE OURSELVES Paul Mercier WOP DAC SACRIFICE Peter Dowling SFP MY NAME IS EMILY Simon Fitzmaurice Hurricane Films DEBRIS Mark O Rowe Parallel Films LOVE ETERNAL Brendan Muldowney Fastnet Films CALVARY John McDonagh Bruno Films HEREAFTER Clint Eastwood Warner Bros BASKET CASE Owen O’Neil Blinder Films HONEST David A Stewart Honest Prods THE TROUBLE WITH SEX Fintan Connelly Fubar Films ALL SOULS DAY Alan Gilsenan Yellow Asylum Films ROMAN SPRING OF MRS STONE Robert Ackerman HBO TELEVISION includes IRISH CRIME STORY Zuli Aladay Cairde Films COUNSEL Declan Recks Lacada THE BAILOUT Conall Morrison Whitefriar Films VIKINGS IV Ken Girotti VK Prods INSPECTOR JURY Florian Kern IJ Prods AMBER Thaddeus O’Sullivan RTE RAW Various Ecossse / RTE FAIR CITY Various RTE SINGLE HANDED Various Touchpaper / RTE TROUBLE IN PARADISE Various Great Western / RTE HIDE AND SEEK Dearbhla Walsh Accomplice PROOF Ciaran Donnelly Subotica / RTE THE TUDORS Steve Shill Showtime BACHELORS WALK John Carney RTE / BBC HOT HOUSE Cilla Ware Channel 4 DANGERFIELD Laurence Gordon Clark BBC THE FAMILY Michael Winterbottom BBC Cont.. 24 Adelaide Street, Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin T: 1 663 8646 www.macfarlane-chard.ie Registered in Ireland Co No: 422112I VAT no: IE 6442112F. Registered under the Data Protection Act Registered Office: 32 Upper Mount Street, Dublin 2 Page 2 DECLAN CONLON THEATRE IRELAND includes Brian in COME ON HOME Rachel O’Riordan Peacock Theatre Turlough in NORA Eoghan Carrick Corn -

Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role-Playing Video Games

University of Huddersfield Repository Jennifer, Smith Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role Playing Video Games Original Citation Jennifer, Smith (2020) Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role Playing Video Games. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/35389/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Worldbuilding Voices in the Soundscapes of Role-Playing Video Games Jennifer Caron Smith A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield October 2020 1 Copyright Statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/ or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and s/he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. -

Theater in England Syllabus 2010

English 252: Theatre in England 2010-2011 * [Optional events — seen by some] Monday December 27 *2:00 p.m. Sleeping Beauty. Dir. Fenton Gay. Sponsored by Robinsons. Cast: Brian Blessed (Star billing), Sophie Isaacs (Beauty), Jon Robyn (Prince), Tim Vine (Joker). Richmond Theatre *7:30 p.m. Mike Kenny. The Railway Children (2010). Dir. Damian Cruden. Music by Christopher Madin. Sound: Craig Veer. Lighting: Richard G. Jones. Design: Joanna Scotcher. Based on E. Nesbit’s popular novel of 1906, adapted by Mike Kenny. A York Theatre Royal Production, first performed in the York th National Railway Museum. [Staged to coincide with the 40 anniversary of the 1970 film of the same name, dir. Lionel Jefferies, starring Dinah Sheridan, Bernard Cribbins, and Jenny Agutter.] Cast: Caroline Harker (Mother), Marshall Lancaster (Mr Perks, railway porter), David Baron (Old Gentleman/ Policeman), Nicholas Bishop (Peter), Louisa Clein (Phyllis), Elizabeth Keates Mrs. Perks/Between Maid), Steven Kynman (Jim, the District Superintendent), Roger May (Father/Doctor/Rail man), Blair Plant(Mr. Szchepansky/Butler/ Policeman), Amanda Prior Mrs. Viney/Cook), Sarah Quintrell (Roberta), Grace Rowe (Walking Cover), Matt Rattle (Walking Cover). [The production transforms the platforms and disused railway track to tell the story of Bobby, Peter, and Phyllis, three children whose lives change dramatically when their father is mysteriously taken away. They move from London to a cottage in rural Yorkshire where they befriend the local railway porter and embark on a magical journey of discovery, friendship, and adventure. The show is given a touch of pizzazz with the use of a period stream train borrowed from the National Railway Museum and the Gentlemen’s saloon carriage from the famous film adaptation.] Waterloo Station Theatre (Eurostar Terminal) Tuesday December 28 *1:45 p.m. -

Curriculum Vitae

Ginny Schiller CDG 9 Clapton Terrace London E5 9BW Casting Director Tel: 020 8806 5383 Mob: 07970 517667 [email protected] curriculum vitae I am an experienced casting director with nearly 20 years in the industry. My casting career began at the Royal Shakespeare Company in 1997 and I went freelance in 2001. I have collaborated on hundreds of productions with dozens of directors, producers and venues, and although my main focus has always been theatre, I have also cast for television, film, radio and commercials. I have been an in-house casting director for Chichester Festival Theatre, Rose Theatre Kingston, English Touring Theatre and Soho Theatre and returned to the RSC in 2005/6 to lead the casting for the Complete Works Season. I currently work closely with Danny Moar on many of the shows for Theatre Royal Bath Productions and with Laurence Boswell at the Ustinov Studio Theatre. I have cast for independent commercial producers as well as the subsidised sector, for the touring circuit, regional, fringe and West End venues, including the Almeida, Arcola, ATG, Birmingham Rep, Bolton Octagon, Bristol Old Vic, City of London Sinfonia, Clwyd Theatr Cyrmu, Frantic Assembly, Greenwich Theatre, Hampstead Theatre, Headlong, Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse, Lyric Theatre Belfast, Marlowe Studio Canterbury, Menier Chocolate Factory, New Wolsey Ipswich, Norfolk & Norwich Festival, Northampton Royal & Derngate, Oxford Playhouse, Plymouth Theatre Royal and Drum, Regent's Park Open Air Theatre, Shared Experience, Sheffield Crucible, Sonia Friedman Productions, Theatre Royal Haymarket, Touring Consortium, Young Vic, West Yorkshire Playhouse, Yvonne Arnaud and Wilton’s Music Hall. I am currently on the committee of the Casting Directors’ Guild, and actively involved in discussions with Equity regarding the casting process and diversity issues across the media. -

Derek Hutchinson

Eamonn Bedford Agency 1st Floor - 28 Mortimer Street London W1W 7RD EBA t +44(0) 20 7734 9632 e [email protected] represented by Eamonn Bedford www.eamonnbedford.agency DEREK HUTCHINSON HEIGHT: 5’9” (175cm) HAIR: Blonde EYES: Grey-Green TITLE (Role) DIRECTOR PRODUCTION COMPANY TELEVISION The Tuckers (Mr Jarrett) Ian Fitzgibbon BBC George Gently - Series 9 (Brian) Robert Del Maestro BBC/Company Pictures Vera (Jeb Branning) Louise Hooper ITV Holby City (George Driscoll) Louise Hooper BBC Doctors (Alun Clay) Matt Carter BBC Versailles (Giovanni Cassini) Daniel Roby Canal + The Casual Vacancy (Vicar) Jonny Campbell BBC/HBO Endeavour II (Chief Constable Standish) Geoff Sax Mammoth Screen for ITV By Any Means (Arthur Rose) Mark Everest Red Planet Ltd Crimes Against Fashion (Court Clerk) Southan Morris Storyvault Films Stella (Hotel Manager) Sue Tully Tidy Productions Ltd Doctors (Bob Peters) Di Patrick BBC Marple (Concierge) Dave Moore ITV Doctors (Tom) Justin Edgar BBC Midsomer Murders (Richard Budd) Peter Smith Bentley Productions (for ITV) Spooks (Robert Cash) Julian Holmes Kudos Spooks Ltd Stand By Your Man (Detective Sergeant) Paul Wilmhurst Betty TV Ltd Midsomer Murders (Milkman) Renny Rye ITV The Bill Chris Lovett Thames/Pearson London’s Burning (Ron) Tim Leandro ITV Chef (The Cheese Supplier) John Birkin Monkey Games Ltd Crimewatch File (DC Russell Paul) Teresa Hunt BBC Waiting (MacIntyre) Charlie Hanson Mentorn Films Trainer (A&E Doctor) Peter Rose BBC The Life And Death Of Philip Knight (Prison Officer) Peter Kosminsky BBC THEATRE -

Appendix 1: Simon Stephens – Interview

Appendix 1: Simon Stephens – Interview This interview took place as a public event for a predominantly student audience at the University of Kent on 6 March 2012. It was originally organized by Peter Boenisch and sponsored by the European Theatre Research Network (ETRN). Prior to the inter- view, I screened the trailers of the 2007 German production and the 2008 British production of Stephens’s play Pornography. RADOSAVLJEVIC´: In your lecture ‘Skydiving Blindfolded’, delivered at the Berlin fes- tival last year, you summarize your points on what you’ve learnt from working with a German director. What interested me was: (1) the observation that the English process of rehearsal tends to involve ‘standing the original conception as described by the writer on its feet’, whereas a German director would re-imagine the play, and (2) another more contextual observation that in the German-speaking world, ‘one of the highest manifestations of excellence is to be invited to a festival’ whereas in Britain it is ‘the possibility of a commercial transfer’. This forms a very insightful encapsulation of differences between those contexts. How did you come to playwriting in the first instance, and how did that experience of working in Germany change your process as a playwright? STEPHENS: The play Pornography was a play I wrote in 2005 about the bomb- ing of London on the London Underground system. The world premiere was directed by Sebastian Nübling – a German direc- tor, from the South of Germany. He’s directed five of my plays now and he’s a dear friend and an important colleague and col- laborator. -

Neil Austin Lighting Designer

Neil Austin Lighting Designer Neil Austin - Lighting Designer is a triple Tony award and double Olivier award winner, designing internationally for plays, musicals opera and dance. Agents Rose Cobbe Assistant Florence Hyde [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0957 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes AFTER LIFE National Theatre in co- Dir. Jeremy Herrin 2021 production with Headlong FROZEN Disney, Theatre Royal Dir. Michael Grandage 2021 Drury Lane LEOPOLDSTADT Sonia Friedman Dir. Patrick Marber 2020 - 2021 Productions, Wyndhams Theatre BLUES IN THE NIGHT Kiln Theatre Dir. Susie McKenna 2019 THE NIGHT OF THE IGUANA Noël Coward Theatre Dir. James Macdonald 2019 THE HUNT Almeida Theatre Dir. Rupert Goold 2019 BITTER WHEAT Garrick Theatre Dir. David Mamet 2019 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE STARRY MESSENGER Wyndham's Theatre Dir. Sam Yates 2019 ROSMERSHOLM Duke of York's Theatre Dir. Ian Rickson 2019 COMPANY Gielgud Theatre, West Dir. Marianne Elliott 2018 End TRANSLATIONS National Theatre Written by Brian Friel; Dir. Ian Rickson 2018 THE LIEUTENANT OF Noel Coward Theatre, Dir. Michael Grandage INISHMORE West End 2018 RED Wyndham's Theatre, Dir. Michael Grandage 2018 West End TRAVESTIES Roundabout Theatre, Dir. Patrick Marber 2018 Broadway SEAFARER SEAFARER NY L.L.C 2017 ALBION Almeida Theatre Dir: Rupert Goold 2017 LABOUR OF LOVE Headlong Dir: Jeremy Herrin 2017 INK Almeida Theatre / Duke Dir: Rupert Goold 2017 of York's Theatre WOYZECK Old Vic Theatre Dir: Joe Murphey 2017 THE TREATMENT Almeida Theatre Dr: Lyndsey Turner 2017 THE GOAT Playful UK / Theatre Dir: Ian Rickson 2017 Royal Haymarket TRAVESTIES Sonia Friedman Dr: Patrick Marber 2017 Productions / Apollo Theatre BURIED CHILD ATG Dir: Scott Elliott 2016 TRAVESTIES Menier Chocolate Dir Patrick Marber 2016 Factory THE ENTERTAINER Fiery Angel Dir Rob Ashford 2016 HARRY POTTER AND THE Sonia Friedman A new play by Jack Thorne. -

Declan Conlon

DECLAN CONLON Height: 6’ Eyes: Grey / Green Hair: Black FILM includes: director WE OURSELVES Paul Mercier WOP DAC SACRIFICE Peter Dowling SFP MY NAME IS EMILY Simon Fitzmaurice Hurricane Films DEBRIS Mark O Rowe Parallel Films LOVE ETERNAL Brendan Muldowney Fastnet Films CALVARY John McDonagh Bruno Films HEREAFTER Clint Eastwood Warner Bros BASKET CASE Owen O’Neil Blinder Films HONEST David A Stewart Honest Prods THE TROUBLE WITH SEX Fintan Connelly Fubar Films ALL SOULS DAY Alan Gilsenan Yellow Asylum Films ROMAN SPRING OF MRS STONE Robert Ackerman HBO TELEVISION includes IRISH CRIME STORY Zuli Aladay Cairde Films COUNSEL Declan Recks Lacada THE BAILOUT Conall Morrison Whitefriar Films VIKINGS IV Ken Girotti VK Prods INSPECTOR JURY Florian Kern IJ Prods AMBER Thaddeus O’Sullivan RTE RAW Various Ecossse / RTE FAIR CITY Various RTE SINGLE HANDED Various Touchpaper / RTE TROUBLE IN PARADISE Various Great Western / RTE HIDE AND SEEK Dearbhla Walsh Accomplice PROOF Ciaran Donnelly Subotica / RTE THE TUDORS Steve Shill Showtime BACHELORS WALK John Carney RTE / BBC HOT HOUSE Cilla Ware Channel 4 DANGERFIELD Laurence Gordon Clark BBC THE FAMILY Michael Winterbottom BBC Cont.. 24 Adelaide Street, Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin T: 1 663 8646 www.macfarlane-chard.ie Registered in Ireland Co No: 422112I VAT no: IE 6442112F. Registered under the Data Protection Act Registered Office: 32 Upper Mount Street, Dublin 2 Page 2 DECLAN CONLON THEATRE IRELAND includes Brian in COME ON HOME Rachel O’Riordan Peacock Theatre Turlough in NORA Eoghan Carrick Corn -

S T E P H E N U N W I N Cv

S T E P H E N U N W I N Curriculum Vitae Theatre and Opera Director Writer and Teacher Stephen Unwin was born in Budapest in 1959. He read English at Cambridge University, where he studied under Margot Heinemann. He directed and de- signed fifteen student productions. These included an award-winning produc- tion of Measure for Measure that transferred to the Almeida Theatre from the 1981 Edinburgh Festival. As a result, he was awarded an Arts Council of Great Britain Trainee Director’s Bursary to worK at the Almeida for a year. Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh For much of the 1980s, Stephen was Associate Director of the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh. All of his productions there were of new plays from Scotland, Eng- land and abroad, including Chris Hannan’s Elizabeth Gordon Quinn and The Or- phans’ Comedy, Peter Arnott’s White Rose and Elias Sawney and Peter Jukes’ Abel Barebone and Shadowing the Conqueror. Six of his productions transferred to London theatres: Michel Tremblay's Sandra/Manon (Donmar Warehouse); Mario Vargas Llosa's Kathie and the Hippopotamus and Peter Arnott's White Rose (Al- meida); John McKay's Dead Dad Dog (Royal Court Theatre Upstairs); and the British premieres of two plays by Manfred Karge: the Time Out Award-winning Man to Man (with Tilda Swinton) and The Conquest of the South Pole (with Alan Cumming), (both to the Royal Court). Actors Stephen directed at the Traverse include Simon Russell Beale, Ewen Bremner, Katrin Cartlidge, Alan Cumming, Kathryn Hunter, Tilda Swinton and Ken Stott. National Theatre In the early 1990s, Stephen was Resident Director at the National Theatre Studio, where his work included: Marivaux’ The Lottery of Love; Goethe's Torquato Tasso (Cottesloe); the anonymous A Yorkshire Tragedy (Cottesloe); Shakespeare’s Poor; Terry Heaton's Echoes of a Revolution; the British premiere of Peter HandKe's The Long Way Round (Cottesloe); and his devised show for the under-fives The Magic Carpet for the RNT Education Department (Cottesloe and Olivier).