The Perception and Socially Constructed Practises of Dental Sedation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates

University of Central Florida STARS Honors Undergraduate Theses UCF Theses and Dissertations 2019 Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates Gary M. Bogers University of Central Florida Part of the Music Commons, and the United States History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the UCF Theses and Dissertations at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Undergraduate Theses by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Bogers, Gary M., "Music and the Presidency: How Campaign Songs Sold the Image of Presidential Candidates" (2019). Honors Undergraduate Theses. 511. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses/511 MUSIC AND THE PRESIDENCY: HOW CAMPAIGN SONGS SOLD THE IMAGE OF PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES by GARY MICHAEL BOGERS JR. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Honors in the Major Program in Music Performance in the College of Arts and Humanities and in The Burnett Honors College at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term, 2019 Thesis Chair: Dr. Scott Warfield Co-chairs: Dr. Alexander Burtzos & Dr. Joe Gennaro ©2019 Gary Michael Bogers Jr. ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I will discuss the importance of campaign songs and how they were used throughout three distinctly different U.S. presidential elections: the 1960 campaign of Senator John Fitzgerald Kennedy against Vice President Richard Milhouse Nixon, the 1984 reelection campaign of President Ronald Wilson Reagan against Vice President Walter Frederick Mondale, and the 2008 campaign of Senator Barack Hussein Obama against Senator John Sidney McCain. -

The Prayer of Jabez by Bruce Wilkingson Lesson V

1 The Prayer of Jabez By Bruce Wilkingson Lesson V “Keeping The Legacy Safe” “O That You Would Keep Me From Evil” 1 Chronicles 4:9-10 9) And Jabez was more honourable than his brethren: and his mother called his name Jabez, saying, Because I bare him with sorrow. 10) And Jabez called on the God of Israel, saying, Oh that thou wouldest bless me indeed, and enlarge my coast, and that thine hand might be with me, and that thou wouldest keep me from evil, that it may not grieve me! And God granted him that which he requested. Introduction: 1. A caption read “Sometimes you can afford to come in second. Sometimes you cannot.” a. This was placed under a Roman Gladiator who was in trouble. b. Here is the picture i. The Gladiator has dropped his sword ii. The enraged lion is in mid lunge with his jaws wide iii. The crowd is on their feet watching in horror as the panic-stricken gladiator tries to flee. Note: This is a horrible time to come in second. 2. Jabez had asked for supernatural blessing, influence, and power. a. Many people think that they can jump into any arena with any lion, “and win.” b. Some people with the hand of God upon them might pray “Lord, Keep me through evil,” but not Jabez. i. Jabez prayed “Keep me from evil.” ii. The best way to defeat a roaring lion is to stay out of the arena. 2 iii. Therefore Jabez prayed “Keep me from evil” which was a prayer that is saying: “God, keep me out of the fight.” 3. -

Representations of Female Adolescence in the Teen Makeover Film

Representations of Female Adolescence in the Teen Makeover Film By Kendra Marston A Thesis Submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Degree of Master of Arts in Film Victoria University of Wellington 2010 Abstract This thesis proposes to analyse the representation of female adolescence in the contemporary teen makeover film. The study will situate this body of films within the context of the current postfeminist age, which I will argue has bred specific fears both of and for the female adolescent. This thesis will examine the construction of the initial wayward makeover protagonist, paying attention to why she needs to be trained in an idealised gender performance that has as its urgent goal the assurance of heteronormativity and ‘healthy’ sex role power relations. I will also analyse the representation of deviant adolescent female characters in terms of how their particular brand of postfeminist female masquerade masks a power and status-oriented agenda. The behaviour of these characters is shown to impact negatively on the peer group within the film, and is particularly dangerous as it threatens to negate the need for romance. 1 Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One 23 Chapter Two 62 Chapter Three 86 Chapter Four 112 Conclusion 132 Bibliography 143 Filmography 153 Television Sources 155 Internet Sources 157 2 Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my supervisor Sean Redmond for the time he put in to helping me with this thesis, as well as for the encouragement, support and advice offered. 3 Introduction My Moment of Awakening in the Makeover Moment While watching The Princess Diaries (Garry Marshall, 2001) for the purpose of this research, I became fascinated by the particular tone of its makeover scene. -

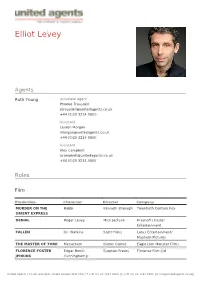

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

"So Very," "So Fetch": Constructing Girls on Film in the Era of Girl Power and Girls in Crisis

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses Studies 11-19-2008 "So Very," "So Fetch": Constructing Girls on Film in the Era of Girl Power and Girls in Crisis Mary Larken McCord Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses Recommended Citation McCord, Mary Larken, ""So Very," "So Fetch": Constructing Girls on Film in the Era of Girl Power and Girls in Crisis." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2008. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/wsi_theses/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute for Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “SO VERY,” “SO FETCH”: CONSTRUCTING GIRLS ON FILM IN THE ERA OF GIRL POWER AND GIRLS IN CRISIS by MARY LARKEN MCCORD Under the Direction of Amira Jarmakani ABSTRACT In the mid-1990s, two discourses of girlhood emerged in both the popular and academic spheres. Consolidated as the girl power discourse and girls in crisis discourse, the tension between these two intertwined discourses created a space for new narratives of female adolescence in the decade between 1995 and 2005. As sites of cultural construction and representation, teen films reveal the narratives of girlhood. The films under consideration serve as useful exemplars for an examination of how such discourses become mainstreamed, pervading society’s image of female adolescence. -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017 Hosted by Elder Conservatorium of Music, The University of Adelaide. September 28th to October 1st, 2017 Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017, Adelaide, South Australia Keynote Speaker: Professor Takashi Ikegami Published by The Australasian University of Tokyo Computer Music Association Paper & Performances Jury: http://acma.asn.au Stephen Barrass September 2017 Warren Burt Paul Doornbusch ISSN 1448-7780 Luke Dollman Luke Harrald Christian Haines All copyright remains with the authors. Cat Hope Robert Sazdov Sebastian Tomczak Proceedings edited by Luke Harrald & Lindsay Vickery Barnabas Smith. Ian Whalley Stephen Whittington All correspondence with authors should be Organising Committee: sent directly to the authors. Stephen Whittington (chair) General correspondence for ACMA should Michael Ellingford be sent to [email protected] Christian Haines Luke Harrald Sue Hawksley The paper refereeing process is conducted Daniel Pitman according to the specifications of the Sebastian Tomczak Australian Government for the collection of Higher Education research data, and fully refereed papers therefore meet Concert / Technical Support Australian Government requirements for fully-refereed research papers. Daniel Pitman Michael Ellingford Martin Victory With special thanks to: Elder Conservatorium of Music; Elder Hall; Sud de Frank; & OzAsia Festival. DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF COMPUTER MUSIC? COMPUTER MUSIC IN THE AGE OF MACHINE -

Oracle Arena from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Coordinates: 37°45′1″N 122°12′11″W Oracle Arena From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Oracle Arena (originally OaklandAlameda County Coliseum Arena, formerly The Arena in Oakland and Oracle Arena Oakland Arena and commonly Oakland Coliseum Arena) is an indoor arena located in Oakland, California. It is the home of the Golden State Warriors. It has a capacity of 19,596, making it the largest of the three NBA arenas in California by capacity, with the Staples Center in Los Angeles (the current home of both the Lakers and Clippers) second and the Sleep Train Arena in Sacramento third. It is the oldest arena in the NBA. Contents 1 History Former OaklandAlameda County Coliseum names Arena (1966–96) 1.1 Home franchises The Arena in Oakland (1997–2005) 1.2 Renovation Oakland Arena (2005–06) Location 7000 Coliseum Way 1.3 The Oracle Oakland, CA 94621 Coordinates 37°45′1″N 122°12′11″W 1.4 Attendance records Public Oakland Coliseum Station 2 The Future transit Owner OaklandAlameda County Coliseum 3 Seating capacity Authority Operator AEG 3.1 Notable events Capacity Basketball: 19,596 4 See also Concert: 20,000 Ice hockey: 13,601 (1966–1997), 5 References 17,200 (1997–2018) Construction 6 External links Broke April 15, 1964 ground November 9, 1966 History Opened Renovated 1996–97 Home franchises Construction $25 million (original) cost ($191 million in 2015 dollars[1])[2] The arena has been the home to the Golden State $121 million (1996–97 renovation) [3] Warriors since 1971, except the oneyear hiatus while the ($183 million in 2015 dollars[1]) arena was undergoing renovations. -

God and the Engineer: an Integration Paper

God and the Engineer: An Integration Paper by Timothy R. Tuinstra Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Electrical Engineering Cedarville University Email: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION versity. This discussion then leads naturally into a discussion of the epistemological and philosophical Cedarville University exists to equip Christian underpinnings of engineering within the framework students for lifelong leadership and service marked of biblical Christianity in Section III. In Section IV by excellence and grounded in biblical truth. So I take up the biblical view of vocation or calling and states the mission statement of this great institu- deal specifically with engineering as a legitimate tion. The challenge for her faculty is to flesh out calling for Christian men and women. In Section this mission in individual courses, laboratories, and V I address the need for a sense of moderation interactions with students across the campus. This is concerning our conception of what engineering and the mandate of “biblical integration”. The challenge technology can do for mankind in a fallen world. for Christian professors is to see the whole realm Finally, in Section VI I describe how we may make of knowledge holistically and to teach their students specific applications in the engineering classroom. to do the same. Greg Bahnsen describes well the task of integration when he says, “...God’s word II. WHY CHRISTIAN HIGHER EDUCATION? demands unreserved allegiance to God and His truth As we enter the 21st century, many Christian in all our thought and scholarly endeavors [1].” The thinkers are becoming alarmed at the growing num- believing professor then has no choice but to get ber of Christian young people whose thinking is down to business in the task of integrating. -

Prayerconnect Connecting to the Heart of Christ Through Prayer

PREMIERE ISSUE, VOL. 1, NO. 1 PRAYERCONNECT Connecting to the Heart of Christ through Prayer Can Prayer save america? 7 Circles of Power Prayer Guide | What’s It Mean to Contend? The FULL REVELATION of God You don’t have a prayer? Let Harvest Prayer Ministries help! Let us help you start a prayer revolution —an army of believers praying the purposes of God for their neighbors, your church, and the nations. Do an all-church 30-day prayer initiative with our new outreach-focused prayer guide. Dave Butts Jon Graf This 30-day prayer guide from veteran prayer lead- ers Dave and Kim Butts, is Let Harvest Prayer Ministry having a powerful effect in teachers Dave Butts or churches across the coun- try. Why not engage your Jon Graf fire up and equip people in 30 days of prayer your congregation to pray for neighbors and nations, as never before. using this guide. Call 812-238-5504 or go to For information on ordering, go to www.harvestprayer.com and click on www.prayershop.org, Teaching|Teaching Ministry for information click on Restoration Revolution on hosting a prayer weekend. Ch u r C h Harvest Prayer r a y e r e a d e r s Ministries Pr ayerShop P L Publishing Ne t w o r k www.harvestprayer.com www.prayershop.org www.prayerleader.com PRAYERConnect You don’t have a prayer? 8 Premiere Issue • Vol. 1, No. 1 Can Prayer Save America? 8 Show Me the Proof A Historical Look at How Prayer Turned the Tide in U.S. -

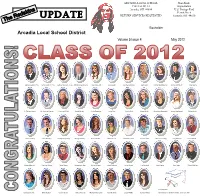

Spring 2012 UPDATE

ARCADIA LOCAL SCHOOL Non-Profit 19033 St. Rt. 12 Organization s Arcadia, OH 44804 U.S. Postage Paid kin Permit No. 6 ds RETURN SERVICES REQUESTED R e UPDATE Fostoria, OH 44830 The Boxholder Arcadia Local School District Volume 5 Issue 4 May 2012 James Graham, Pres. Tanner Cole, V. Pres. Kathryn Duncan, Treas. Johnston Baird, Secy. Raven Aurand Grant Baker Stephanie Below Jade Bolen Hannah Brandeberry Dirk Breidenbach Hope Burns R. Trevor Colman M. Michael Cramer Dominick Diller Cierah Feasel Annie Firestone Lucas Fox Alysha Funk Kirsten Glick Samantha Greenwell Jessica Hackworth Caleb Harris Loren Huntley Lucas Huntley Kathryn Kapostasy Meeghan Kelly Jessica KneƩle Miranda Leal Dakota Lenhart Connor Lewis Brandon Ludwig Amy Mathias Lane MelloƩ Kelsey Morrison Shannon Moses Chase Myers Zabreannon Nye Serina Philipps Kacie Pohlman Lucas Recker Eric Reinhart Seth Riegle Evan Riggs GarreƩ Schling Not pictured: Danielle Sherick Britni Slayter Connor Smith Hailey Thomas Mariyah Thompson Kyle Wellman Lucas WhiƩa Kendra Wilkins Baili Bostwick, MaƩhew Smith, Jacob Van AƩa Page 2 The Redskins UPDATE May 2012 From the Superintendent ~ Laurie Walles The 2011-12 school year is quickly drawing to a close. This year has flown by in a flurry of student achievements and activities. As we conclude another successful year of school at Arcadia Lo- cal, a huge THANK YOU to the community for your continued support of education through passage of the two Emergency levy renewals in March. The support demonstrated for this district finan- cially and through community collaboration truly enables the success of the district. As the school year ends, I want to take this opportunity to recognize and thank three dedicated employees who will be retiring from the district this year. -

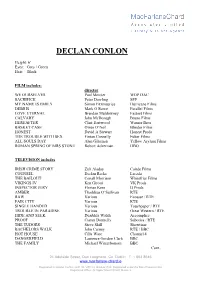

Declan Conlon

DECLAN CONLON Height: 6’ Eyes: Grey / Green Hair: Black FILM includes: director WE OURSELVES Paul Mercier WOP DAC SACRIFICE Peter Dowling SFP MY NAME IS EMILY Simon Fitzmaurice Hurricane Films DEBRIS Mark O Rowe Parallel Films LOVE ETERNAL Brendan Muldowney Fastnet Films CALVARY John McDonagh Bruno Films HEREAFTER Clint Eastwood Warner Bros BASKET CASE Owen O’Neil Blinder Films HONEST David A Stewart Honest Prods THE TROUBLE WITH SEX Fintan Connelly Fubar Films ALL SOULS DAY Alan Gilsenan Yellow Asylum Films ROMAN SPRING OF MRS STONE Robert Ackerman HBO TELEVISION includes IRISH CRIME STORY Zuli Aladay Cairde Films COUNSEL Declan Recks Lacada THE BAILOUT Conall Morrison Whitefriar Films VIKINGS IV Ken Girotti VK Prods INSPECTOR JURY Florian Kern IJ Prods AMBER Thaddeus O’Sullivan RTE RAW Various Ecossse / RTE FAIR CITY Various RTE SINGLE HANDED Various Touchpaper / RTE TROUBLE IN PARADISE Various Great Western / RTE HIDE AND SEEK Dearbhla Walsh Accomplice PROOF Ciaran Donnelly Subotica / RTE THE TUDORS Steve Shill Showtime BACHELORS WALK John Carney RTE / BBC HOT HOUSE Cilla Ware Channel 4 DANGERFIELD Laurence Gordon Clark BBC THE FAMILY Michael Winterbottom BBC Cont.. 24 Adelaide Street, Dun Laoghaire, Co. Dublin T: 1 663 8646 www.macfarlane-chard.ie Registered in Ireland Co No: 422112I VAT no: IE 6442112F. Registered under the Data Protection Act Registered Office: 32 Upper Mount Street, Dublin 2 Page 2 DECLAN CONLON THEATRE IRELAND includes Brian in COME ON HOME Rachel O’Riordan Peacock Theatre Turlough in NORA Eoghan Carrick Corn