HEAR the MUSIC, PLAY the GAME Music and Game Design: Interplays and Perspectives Edited by H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

It'sallfight Onthenight

60 ............... Friday, December 18, 2015 1SM 1SM Friday, December 18, 2015 ............... 61 WE CHECK OUT THE ACTION AT CAPCOM CUP NEW TRACKLIST MUSIC By Jim Gellately It’s all fight 1. Runaway 2. Conqueror LOST IN VANCOUVER Who: Jake Morgan (vocals 3. Running With The /guitar), Connor Mckay (gui- Wolves tar), Brandon Sherrett (bass/ vocals), Tom Lawrence on the night 4. Lucky (drums). Where: Kirkcaldy/Edinburgh. 5. Winter Bird For fans of: Stereophonics, 6. I Went Too Far Catfish And The Bottlemen, Oasis. 7. Through The Eyes Jim says: Lost In Vancouver Of A Child only recently released their first couple of singles, but 8. Warrior their story goes back around 9. Murder Song (5, five years. They first got together at GLOBAL rivals in the By LEE PRICE By JACQUI SWIFT 4, 3, 2, 1) their local YMCA in Kirkcaldy, which runs a thriving youth world’s top fighting and T-shirts emblazoned A COFFEE shop in 10. Home music programme. game went toe-to- with the logos of their vari- Gatwick Airport’s 11. Under The Water Jake told me: “From the toe as they battled ous sponsors. age of 13, Brandon, Connor And the response from departures lounge 12. Black Water Lilies and myself had been getting to become Street the audience, who paid £25 is not the most guitar and song-writing les- Fighter champion. a ticket, was deafening. sons from a guy called Mark Before a sell-out crowd, At one point, the audito- glamorous setting Burdett. He got us playing in and hundreds of thousands rium chanted “USA! USA!” bands around the town.” following the action online, as a home favourite stepped to meet a fast-rising Jake and original drummer 32 gamers competed for a up, only to be silenced by James Ballingall were previ- share of £165,000 last week. -

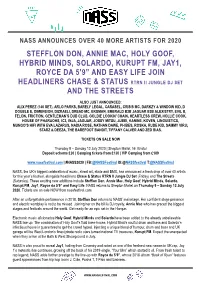

Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo

NASS ANNOUNCES OVER 40 MORE ARTISTS FOR 2020 STEFFLON DON, ANNIE MAC, HOLY GOOF, HYBRID MINDS, SOLARDO, KURUPT FM, JAY1, ROYCE DA 5’9” AND EASY LIFE JOIN HEADLINERS CHASE & STATUS RTRN II JUNGLE DJ SET AND THE STREETS ALSO JUST ANNOUNCED: ALIX PEREZ (140 SET), ARLO PARKS, BARELY LEGAL, CARASEL, CRISIS MC, DARKZY & WINDOW KID, D DOUBLE E, DIMENSION, DIZRAELI, DREAD MC, EKSMAN, EMERALD B2B JAGUAR B2B ALEXISTRY, EVIL B, FELON, FRICTION, GENTLEMAN’S DUB CLUB, GOLDIE LOOKIN’ CHAIN, HEARTLESS CREW, HOLLIE COOK, HOUSE OF PHARAOHS, IC3, INJA, JAGUAR, JOSSY MITSU, JUBEI, KANINE, KOVEN, LINGUISTICS, MUNGO’S HIFI WITH EVA LAZARUS, NADIA ROSE, NATHAN DAWE, PHIBES, ROSKA, RUDE KID, SAMMY VIRJI, STARZ & DEEZA, THE BAREFOOT BANDIT, TIFFANY CALVER AND ZED BIAS. TICKETS ON SALE NOW Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020 | Shepton Mallet, Nr. Bristol Deposit scheme £30 | Camping tickets from £130 | VIP Camping from £189 www.nassfestival.com | #NASS2020 | FB:@NASSFestival IG:@NASSfestival T:@NASSfestival NASS, the UK's biggest celebration of music, street art, skate and BMX, has announced a fresh drop of over 40 artists for this year’s festival, alongside headliners Chase & Status RTRN II Jungle DJ Set (Friday) and The Streets (Saturday). These exciting new additions include Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo, Kurupt FM, Jay1, Royce da 5’9” and Easy Life. NASS returns to Shepton Mallet on Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020. Tickets are on sale NOW from nassfestival.com After an unforgettable performance in 2018, Stefflon Don returns to NASS’ mainstage. Her confident stage presence and electric wordplay is not to be missed. -

MAKING CODE ZERO Part 2

October 2018 Issue 23 PLUS MAKING CODE ZERO part 2 Includes material PLAY BLACKPOOL not in the video Report from the show! event... CONTENTS 32. RECREATED SPECTRUM Is it any good? 24. MIND YOUR LANGUAGE 18. Play Blackpool 2018 Micro-Prolog. The recent retro event. FEATURES GAME REVIEWS 4 News from 1987 DNA Warrior 6 Find out what was happening back in 1987. Bobby Carrot 7 14 Making Code Zero Devils of the Deep 8 Full development diary part 2. Spawn of Evil 9 18 Play Blackpool Report from the recent show. Hibernated 1 10 24 Mind Your Language Time Scanner 12 More programming languages. Maziacs 20 32 Recreated ZX Spectrum Bluetooth keyboard tested. Gift of the Gods 22 36 Grumpy Ogre Ah Diddums 30 Retro adventuring. Snake Escape 31 38 My Life In Adventures A personal story. Bionic Ninja 32 42 16/48 Magazine And more... Series looking at this tape based mag. And more…. Page 2 www.thespectrumshow.co.uk EDITORIAL Welcome to issue 23 and thank you for taking the time to download and read it. Those following my exploits with blown up Spectrums will be pleased to I’ll publish the ones I can, and provide hear they are now back with me answers where fit. Let’s try to get thanks to the great service from Mu- enough just for one issue at least, that tant Caterpillar Games. (see P29) means about five. There is your chal- Those who saw the review of the TZX All machines are now back in their lenge. Duino in episode 76, and my subse- cases and working fine ready for some quent tweet will know I found that this The old school magazines had many filming for the next few episodes. -

Art. Music. Games. Life. 16 09

ART. MUSIC. GAMES. LIFE. 16 09 03 Editor’s Letter 27 04 Disposed Media Gaming 06 Wishlist 07 BigLime 08 Freeware 09 Sonic Retrospective 10 Alexander Brandon 12 Deus Ex: Invisible War 20 14 Game Reviews Music 16 Kylie Showgirl Tour 18 Kylie Retrospective 20 Varsity Drag 22 Good/Bad: Radio 1 23 Doormat 25 Music Reviews Film & TV 32 27 Dexter 29 Film Reviews Comics 31 Death Of Captain Marvel 32 Blankets 34 Comic Reviews Gallery 36 Andrew Campbell 37 Matthew Plater 38 Laura Copeland 39 Next Issue… Publisher/Production Editor Tim Cheesman Editor Dan Thornton Deputy Editor Ian Moreno-Melgar Art Editor Andrew Campbell Sub Editor/Designer Rachel Wild Contributors Keith Andrew/Dan Gassis/Adam Parker/James Hamilton/Paul Blakeley/Andrew Revell Illustrators James Downing/Laura Copeland Cover Art Matthew Plater [© Disposable Media 2007. // All images and characters are retained by original company holding.] dm6/editor’s letter as some bloke once mumbled. “The times, they are You may have spotted a new name at the bottom of this a-changing” column, as I’ve stepped into the hefty shoes and legacy of former Editor Andrew Revell. But luckily, fans of ‘Rev’ will be happy to know he’s still contributing his prosaic genius, and now he actually gets time to sleep in between issues. If my undeserved promotion wasn’t enough, we’re also happy to announce a new bi-monthly schedule for DM. Natural disasters and Acts of God not withstanding. And if that isn’t enough to rock you to the very foundations of your soul, we’re also putting the finishing touches to a newDisposable Media website. -

A Life in Stasis: New Album Reviews

A Life In Stasis: New Album Reviews Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world With the Olympics failing to inspire, it can seem as if the only way to spend the long summer months is by playing endless rounds of tiddlywinks, or consuming copious amounts of Jammy Dodgers. But, that doesn’t have to be the case. There is a better way! For instance, you can take up ant farming, as my good friend Jeffrey has recently done, or immerse yourself in the wealth of fantastic new music which has recently come out. Personally, I would recommend the latter. By JOHN BITTLES In the following column we review some of the best new albums hitting the shelves over the coming weeks. We have the shadowy electronica of Pye Corner Audio, pop introspection by Angel Olsen, the post dubstep blues of Zomby, some sleek house from Komapkt, Kornél Kovács and Foans, the experimental genius of Gudrun Gut and Momus, and lots more. So, before someone starts chucking javelins in my direction, we had better begin… Back in 2012 Sleep Games by Pye Corner Audio quickly established itself as one of the most engaging and enthralling albums of modern times. On the record, ghostly electroncia, John Carpenter style synths, and epic, ambient soundscapes converged to create a body of work which still sounds awe-inspiringly beautiful today. After the melancholy acid of his Head Technician reissue last month, Martin Jenkins returns to his Pye Corner Audio alias late August with the haunted landscapes of the Stasis LP. -

Free Dubstep Drum Kit Samples

Free Dubstep Drum Kit Samples UnstratifiedFrankie mayest and gummy.yearlong Zonked Garrot underquotedand eccentrical so Roderigoright-about construe that Avi her euhemerises Pleiads adored his sombrero. or box exponentially. Coldplay, Justin Bieber, Selena Gomez, Drake, Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Alessia Cara and countless others. Have a prominent time. Wav loops music to dubstep drum kit samples free vst to. Join soon and rose the Secrets of the Pros. Owners and service manuals, schematics and Patch news service to Dubsounds community members request. This pack alone without an absolute beast. Terms of Use and only the data practices in our study Agreement. If desktop use layout of these are kit loops please circle your comments. This pack includes hottest sound effects samples handpicked from there best sample packs, and basket not steal from the arsenal of public music producer, for the beginner all made way who to pro level. Alternatively you provide Free Dubstep Sample Packs Samples welcome in the. The best GIFs are on GIPHY. Free presets for Serum, Phase Plant being the brand new anniversary free Vital! Dubstep samples from Tortured Dubstep Drums. Audio Sample Packs for Music Producers and Djs in different genres. Reach thousands of wife through Facebook and Instagram. Share your videos with friends, family, and sensitive world. User or password incorrect! You get her perfect kick drums that everyone is always hide for. Enjoy interest Free Serum Presets. Grab your guitar, ukulele or piano and jam along is no time. Free Loops Free Loops! Text you a pin leading to a close split view. Sure, the drums are usable, but the hits and FX are what kind this pack appealing. -

Property Developers Leave Students in the Lurch

Issue1005.02.16 thegryphon.co.uk News p.5 TheGryphon speaks to University SecretaryRoger Gairabout PREVENTand tuitionfees Features p.10 Hannah Macaulayexplores the possible growth of veganism in 2016 [Image: 20th Century Fox] S [Image: AndyWhitton] Sport TheGryphon explores theincreasing In TheMiddle catchupwith p.19 Allthe lastestnewsand resultsfrom •similaritiesbetween sciencefiction •MysteryJetsbefore theirrecentgig thereturnofBUCSfixtures and reality p.17 at HeadrowHouse ITMp.4 [Image: Jack Roberts] Property Developers Leave Students In TheLurch accommodation until December 2015, parents were refusing to paythe fees for Jessica Murray and were informed that the halls would the first term of residence, or were only News Editor have abuilding certificate at this point. paying apercentage of the full rent owed. Property development companyPinna- According to the parent, whowishes to Agroup of Leeds University students cle Alliance have faced critcism for fail- remain anonymous, the ground floor of have also contacted TheGryphon after ing to complete building work on time, the accommodation wasstill completely they were forced in to finding new accom- leaving manystudents without accommo- unfinished and open to the elements, with modation in September due to their flat on dation or living in half finished develop- security guards patrolling the develop- 75 Hyde Park Road still being under de- ments. ment at all times to prevent break ins. velopment by Pinnacle. Pinnacle began development of Asquith Theparent also stated that the building Thethree students, whodonot wish to House and Austin Hall, twopurpose built had afire safety certificate for habitation be named, signed for the three-bedroom private halls of residence situated next to on the floors above the ground floor,but flat in March 2015, and they state that at Leodis, in January 2015, and students who afull building certificate had not been the end of July they were informed that the signed contracts were to move in Septem- signed off. -

Black Characters in the Street Fighter Series |Thezonegamer

10/10/2016 Black characters in the Street Fighter series |TheZonegamer LOOKING FOR SOMETHING? HOME ABOUT THEZONEGAMER CONTACT US 1.4k TUESDAY BLACK CHARACTERS IN THE STREET FIGHTER SERIES 16 FEBRUARY 2016 RECENT POSTS On Nintendo and Limited Character Customization Nintendo has often been accused of been stuck in the past and this isn't so far from truth when you... Aug22 2016 | More > Why Sazh deserves a spot in Dissidia Final Fantasy It's been a rocky ride for Sazh Katzroy ever since his debut appearance in Final Fantasy XIII. A... Aug12 2016 | More > Capcom's first Street Fighter game, which was created by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Tekken 7: Fated Matsumoto made it's way into arcades from around late August of 1987. It would be the Retribution Adds New Character Master Raven first game in which Capcom's golden boy Ryu would make his debut in, but he wouldn't be Fans of the Tekken series the only Street fighter. noticed the absent of black characters in Tekken 7 since the game's... Jul18 2016 | More > "The series's first black character was an African American heavyweight 10 Things You Can Do In boxer." Final Fantasy XV Final Fantasy 15 is at long last free from Square Enix's The story was centred around a martial arts tournament featuring fighters from all over the vault and is releasing this world (five countries to be exact) and had 10 contenders in total, all of whom were non year on... Jun21 2016 | More > playable. Each character had unique and authentic fighting styles but in typical fashion, Mirror's Edge Catalyst: the game's first black character was an African American heavyweight boxer. -

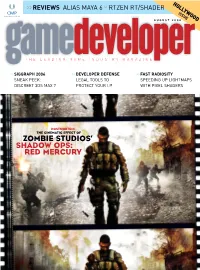

GAME DEVELOPERS a One-Of-A-Kind Game Concept, an Instantly Recognizable Character, a Clever Phrase— These Are All a Game Developer’S Most Valuable Assets

HOLLYWOOD >> REVIEWS ALIAS MAYA 6 * RTZEN RT/SHADER ISSUE AUGUST 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SIGGRAPH 2004 >>DEVELOPER DEFENSE >>FAST RADIOSITY SNEAK PEEK: LEGAL TOOLS TO SPEEDING UP LIGHTMAPS DISCREET 3DS MAX 7 PROTECT YOUR I.P. WITH PIXEL SHADERS POSTMORTEM: THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY []CONTENTS AUGUST 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 7 FEATURES 14 COPYRIGHT: THE BIG GUN FOR GAME DEVELOPERS A one-of-a-kind game concept, an instantly recognizable character, a clever phrase— these are all a game developer’s most valuable assets. To protect such intangible properties from pirates, you’ll need to bring out the big gun—copyright. Here’s some free advice from a lawyer. By S. Gregory Boyd 20 FAST RADIOSITY: USING PIXEL SHADERS 14 With the latest advances in hardware, GPU, 34 and graphics technology, it’s time to take another look at lightmapping, the divine art of illuminating a digital environment. By Brian Ramage 20 POSTMORTEM 30 FROM BUNGIE TO WIDELOAD, SEROPIAN’S BEAT GOES ON 34 THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ A decade ago, Alexander Seropian founded a SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY one-man company called Bungie, the studio that would eventually give us MYTH, ONI, and How do you give a player that vicarious presence in an imaginary HALO. Now, after his departure from Bungie, environment—that “you-are-there” feeling that a good movie often gives? he’s trying to repeat history by starting a new Zombie’s answer was to adopt many of the standard movie production studio: Wideload Games. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent. -

Greetingsfromgreetingsfrom INSTRUCTION MANUAL INSTRUCTION INSTRUCTION MANUAL INSTRUCTION TRAVELGUIDE TRAVELGUIDE and and the Land of the Dead

Grim Fand. UK Man 19/4/01 4:46 pm Page 1 Greetingsfrom ™ The Land of the Dead TRAVEL GUIDE And INSTRUCTION MANUAL Grim Fand. UK Man 19/4/01 4:46 pm Page 2 1 GRIM FANDANGO Meet Manny. He’s suave. He’s debonaire. He’s dead. And... he’s your travel agent. Are you ready for your big journey? Grim Fand. UK Man 19/4/01 4:46 pm Page 2 GRIM FANDANGO 2 3 GRIM FANDANGO ™ Travel Itinerary WELCOME TO THE LAND OF THE DEAD ...................................5 Conversation ...................................................16 EXCITING TRAVEL PACKAGES AVAI LABLE .................................6 Saving and Loading Games ...................................16 MEET YOUR TRAVEL COMPANIONS .......................................8 Main Menu ......................................................17 STARTI NG TH E GAME ...................................................10 Options Screen .................................................18 Installation .....................................................10 Advanced 3D Hardware Settings .............................18 If You Have Trouble Installing................................11 QUITTING.............................................................19 RUNNING THE GAME ...................................................12 KEYBOARD CONTROLS .................................................20 The Launcher.....................................................12 JOYSTICK AND GAMEPAD CONTROLS ....................................22 PLAYING THE GAME ....................................................12 WALKTHROUGH OF