Elizabeth Bay and Potts Point Walk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print This Article

THE HERALDRY OF THE MACLEAYS AND THEIR KIN: THE ARMS OF WILLIAM MACLEAY, HIS SONS, AND THEIR MALE DESCENDANTS Stephen Michael Szabo Heraldic Consultant, Sydney INTRODUCTION In an earlier article1 I gave a brief account of the life of Alexander Macleay following his arrival in Sydney in 1826 and up to his death twenty-two years later. I noted that there had been little or no scholarly examination of the use of coats of arms and similar heraldic identifiers by Alexander Macleay and his kin by either blood or marriage, and ventured that such an examination, which I hoped to carry out, might reveal something about identity, aspiration and kinship in the Scottish diaspora in colonial New South Wales. The present article narrows its focus to look at the ancestry of Alexander Macleay, how his father acquired legitimately granted arms, and what use of these arms was made by various male family members to declare their social status. ANCESTRY The Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB) tells us that Alexander Macleay was: the son of William Macleay, provost of Wick and deputy-lieutenant of Caithness. He was descended from an ancient family which came from Ulster; at the Reformation the family had substantial landholdings in Scotland, but by loyalty to the Stuarts suffered severe losses after the battle of Culloden.2 The ADB entry for Alexander’s son George claims that “the McLeays [were] an old Caithness landed family.”3 The latter is not entirely true, for it seems that the Macleays were newly settled in the late eighteenth century in Caithness, but they had indeed 1 Stephen Michael Szabo, ‘The Heraldry of The Macleays and Their Kin: Scottish Heraldry and Its Australian Context’, Journal of the Sydney Society for Scottish History, Vol. -

Building for the Future Sustainable Spaces Advancing Education & Research

Building For the Future Sustainable Spaces Advancing Education & Research A ‘Group of Eight’ Sustainable Buildings Showcase 2 The ‘Group of Eight’ comprises Australian National University, Monash University, The University of Melbourne, The University of Sydney, The University of Queensland, The University of Western Australia, The University of Adelaide, and The University of New South Wales. 2 SYDNEY UNIVERSITY 3 Building For the Future Australia’s leading research Universities know the leaders of tomorrow, ascend from the foundations of today. At the forefront of an evolving educational landscape, the ‘Group of Eight’ continuously strive to inspire curiosity, challenge thinking, spark innovation and bring education to life through exceptional teaching in exceptional places. This publication showcases a snapshot of those The University Inkarni Wardii 02 of Adelaide places; world-class, high-performance, sustainable facilities which re-define best practice in tertiary Australian National Jaegar 5 04 University education buildings. Built for the future, these spaces Jaegar 8 06 move beyond basic environmental sustainable design Monash University Green Chemical Futures 08 principles to demonstrate what is possible when clever technology and inspired design intersect. Logan Hall 10 Building 56 12 From living laboratories to thermally sound The University Melbourne Brain Centre 14 environments, reusing the old to make new, and of Melbourne optimising for people and purpose — each building The Peter Doherty Institute 16 for Infection & Immunity -

National Architecture Award Winners 1981 – 2019

NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS WINNERS 1981 - 2019 AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARD WINNERS 1 of 81 2019 NATIONAL ARCHITECTURE AWARDS COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Yagan Square (WA) The COLORBOND® Award for Steel Architecture Lyons in collaboration with Iredale Pedersen Hook and landscape architects ASPECT Studios COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE Dangrove (NSW) The Harry Seidler Award for Commercial Architecture Tzannes Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Commercial Architecture Breathe Architecture Private Women’s Club (VIC) National Award for Commercial Architecture Kerstin Thompson Architects EDUCATIONAL ARCHITECTURE Our Lady of the Assumption Catholic Primary School (NSW) The Daryl Jackson Award for Educational Architecture BVN Braemar College Stage 1, Middle School National Award for Educational Architecture Hayball Adelaide Botanic High School (SA) National Commendation for Educational Architecture Cox Architecture and DesignInc QUT Creative Industries Precinct 2 (QLD) National Commendation for Educational Architecture KIRK and HASSELL (Architects in Association) ENDURING ARCHITECTURE Sails in the Desert (NT) National Award for Enduring Architecture Cox Architecture HERITAGE Premier Mill Hotel (WA) The Lachlan Macquarie Award for Heritage Spaceagency architects Paramount House Hotel (NSW) National Award for Heritage Breathe Architecture Flinders Street Station Façade Strengthening & Conservation National Commendation for Heritage (VIC) Lovell Chen Sacred Heart Building Abbotsford Convent Foundation -

The Story of Barncleuth (Later Kinneil)

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND VOL. 33 Edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad Published in Melbourne, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2016 ISBN: 978-0-7340-5265-0 The bibliographic citation for this paper is: Judith O’Callaghan “Trophy House: The Story of Barncleuth (later Kinneil).” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 33, Gold, edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad, 538-549. Melbourne: SAHANZ, 2016. All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may contact the editors. Judith O’Callaghan UNSW Australia TROPHY HOUSE: THE STORY OF BARNCLEUTH (LATER KINNEIL) Kinneil was a rare domestic commission undertaken by the prominent, and often controversial architect, J. J. Clark. Though given little prominence in recent assessments of Clark’s oeuvre, plans and drawings of “Kinneil House,” Elizabeth Bay Road, Sydney, were published as a slim volume in 1891. The arcaded Italianate villa represented was in fact a substantial remodelling of an earlier house on the site, Barncleuth. Built by James Hume for wine merchant John Brown, it had been one of the first of the “city mansions” to be erected on the recently subdivided Macleay Estate in 1852. Brown was a colonial success story and Barncleuth was to be both his crowning glory and parting gesture. Within only two years of the house’s completion he was on his way back to Britain to spend the fortune he had amassed in Sydney. Over the following decades, Barncleuth continued to represent the golden prize for the socially mobile. -

Modern Movement Architecture in Central Sydney Heritage Study Review Modern Movement Architecture in Central Sydney Heritage Study Review

Attachment B Modern Movement Architecture in Central Sydney Heritage Study Review Modern Movement Architecture in Central Sydney Heritage Study Review Prepared for City of Sydney Issue C x January 2018 Project number 13 0581 Modern Movement in Central Sydney x Heritage Study Review EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This study was undertaken to provide a contextual framework to improve understanding post World War II and Modern Movement architecture and places in Central Sydney, which is a significant and integral component of its architectural heritage. Findings x The study period (1945-1975) was an exciting and challenging era that determined much of the present physical form of Central Sydney and resulted in outstanding architectural and civic accomplishments. x There were an unprecedented number of development projects undertaken during the study period, which resulted in fundamental changes to the physical fabric and character of Central Sydney. x The buildings are an historical record of the changing role of Australia in an international context and Sydney’s new-found role as a major world financial centre. Surviving buildings provide crucial evidence of the economic and social circumstances of the study period. x Surviving buildings record the adaptation of the Modern Movement to local conditions, distinguishing them from Modern Movement buildings in other parts of the world. x The overwhelming preponderance of office buildings, which distinguishes Central Sydney from all other parts of NSW, is offset by the presence of other building typologies such as churches, community buildings and cultural institutions. These often demonstrate architectural accomplishment. x The triumph of humane and rational urban planning can be seen in the creation of pedestrian- friendly areas and civic spaces of great accomplishment such as Australia Square, Martin Place and Sydney Square. -

Anzac Parade and Our Changing Narrative of Memory1

Anzac Parade and our changing narrative of memory1 IAN A. DEHLSEN Abstract Australian historian Ken Inglis once called Canberra’s Anzac Parade ‘Australia’s Sacred Way’. A quasi-religious encapsulation of the military legends said to define our national character. Yet, it remains to be discussed how the memorials on Anzac Parade have been shaped by these powerful and pervasive narratives. Each memorial tells a complex story, not just about the conflicts themselves but also the moral qualities the design is meant to invoke. The Anzac Parade memorials chart the changing perceptions of Australia’s military experience through the permanence of bronze and stone. This article investigates how the evolving face of Anzac Parade reflects Australia’s shifting relationship with its military past, with a particular emphasis on how shifting social, political and aesthetic trends have influenced the memorials’ design and symbolism. It is evident that the guiding narratives of Anzac Parade have slowly changed over time. The once all-pervasive Anzac legends of Gallipoli have been complemented by multicultural, gender and other thematic narratives more attuned to contemporary values and perceptions of military service. [This memorial] fixes a fleeting incident in time into the permanence of bronze and stone. But this moment in our history—fifty years ago—is typical of many others recorded not in monuments, but in the memories of our fighting men told and retold … until they have passed into the folklore of our people and into the tradition of our countries.2 These were the words of New Zealand Deputy Prime Minister J.R. Marshall at the unveiling of the Desert Mounted Corps Memorial on Anzac Parade, Canberra, in the winter of 1968. -

'Paper Houses'

‘Paper houses’ John Macarthur and the 30-year design process of Camden Park Volume 2: appendices Scott Ethan Hill A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Faculty of Architecture, Design and Planning, University of Sydney Sydney, Australia 10th August, 2016 (c) Scott Hill. All rights reserved Appendices 1 Bibliography 2 2 Catalogue of architectural drawings in the Mitchell Library 20 (Macarthur Papers) and the Camden Park archive Notes as to the contents of the papers, their dating, and a revised catalogue created for this dissertation. 3 A Macarthur design and building chronology: 1790 – 1835 146 4 A House in Turmoil: Just who slept where at Elizabeth Farm? 170 A resource document drawn from the primary sources 1826 – 1834 5 ‘Small town boy’: An expanded biographical study of the early 181 life and career of Henry Kitchen prior to his employment by John Macarthur. 6 The last will and testament of Henry Kitchen Snr, 1804 223 7 The last will and testament of Mary Kitchen, 1816 235 8 “Notwithstanding the bad times…”: An expanded biographical 242 study of Henry Cooper’s career after 1827, his departure from the colony and reported death. 9 The ledger of John Verge: 1830-1842: sections related to the 261 Macarthurs transcribed from the ledger held in the Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW, A 3045. 1 1 Bibliography A ACKERMANN, JAMES (1990), The villa: form and ideology of country houses. London, Thames & Hudson. ADAMS, GEORGE (1803), Geometrical and Graphical Essays Containing a General Description of the of the mathematical instruments used in geometry, civil and military surveying, levelling, and perspective; the fourth edition, corrected and enlarged by William Jones, F. -

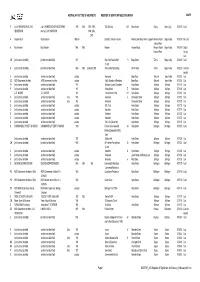

AIA REGISTER Jan 2015

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS REGISTER OF SIGNIFICANT ARCHITECTURE IN NSW BY SUBURB Firm Design or Project Architect Circa or Start Date Finish Date major DEM Building [demolished items noted] No Address Suburb LGA Register Decade Date alterations Number [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1910 Caledonia Hotel 110 Aberdare Street Aberdare Cessnock 4702398 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1905 Denman Hotel 143 Cessnock Road Abermain Cessnock 4702399 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1906 St Johns Anglican Church 13 Stoke Street Adaminaby Snowy River 4700508 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adaminaby Bowling Club Snowy Mountains Highway Adaminaby Snowy River 4700509 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1920 Royal Hotel Camplbell Street corner Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701604 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1936 Adelong Hotel (Town Group) 67 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701605 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelonia Theatre (Town Group) 84 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701606 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Adelong Post Office (Town Group) 80 Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701607 [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Golden Reef Motel Tumut Street Adelong Tumut 4701725 PHILIP COX RICHARDSON & TAYLOR PHILIP COX and DON HARRINGTON 1972 Akuna Bay Marina Liberator General San Martin Drive, Ku-ring-gai Akuna Bay Warringah -

Rare and Curious Specimens, an Illustrated

The attempt of the Philosophical Society of Australasia to create a colonial museum was as premature as its effort to provide a scientific forum. After the demise of the society in 1822, no public interest seems to have been evinced until June 1827 * when a Sydney newspaper offered A HINT- We should be glad to perceive amongst some of our intelligent and public spirited Colonists, more of a drive to prosecute the public weal than at present exists. Amongst other improvements, in these times, would there be any harm in suggesting the idea offounding an AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM? The earlier that such an institution is formed, the better it will be for posterity. 1 What stimulated the hint is unrecorded but it is not unreasonable to suppose that the arrival in Sydney in January 1826 of a new Colonial Secretary may have had something to do with it. Alexander Macleay, FRS, Fellow of the Linnean Society of London and honorary secretary of that prestigious institution from 1798 until1825, had resigned this position at the express request of Earl Bathurst, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to become head of the public service of New South Wales. He was fifty-nine years old when he came to Sydney, having retired from the British civil service on a substantial pension in 1818, but age was no impediment to his activity. He worked in close harmony with Governor Darling and his abrupt dismissal by Governor Bourke in 1837 aroused considerable dissent from the general public of New South Wales, who held him in high esteem as an honest and hard-working administrator. -

MUSE Issue 2, June 2012

issue no. 02 JUL 2012 ART . CULTURE . ANTIQUITIES . NATURAL HISTORY SYDNEY C ONTENTS UNIVERSITY MUSEUMS 01 uniting TO EXplorE FORCES 22 UP CLOSE WITH ART Comprising the Macleay OF NATURE Museum, Nicholson Museum 23 CELEBRATING 50 YEARS: and University Art Gallery 03 GOOD vibrations THE POWER ALUMNI REUNION Open Monday to Friday, 10am to 06 QUTHE EEN AND I 24 naturallY CURIOUS: 4.30pm and the first Saturday of EXploring CORAL every month 12 to 4pm 09 COLLECTING NEW KNOWLEDGE: Closed on public holidays. MACLEAY MUSEUM SPECIAL 26 a controvERSIAL HERO General admission is free. FEaturE Become a fan on Facebook and 28 thE EPIC OF gilgamESH: STATUE follow us on Twitter. SEEING bauhaus IN A NEW LIGHT BRINGS ANCIENT talE to LIFE 16 Sydney University Museums 18 THE curator AND THE cats 30 EVEnts Administration T +61 2 9351 2274 21 maclEAY REAPS BENEfits OF 32 what’S ON F +61 2 9351 2881 FEllowship E [email protected] Education and Public Programs To book a school excursion, an adult education tour or a University heritage tour T +61 2 9351 8746 E [email protected] MACLEAY MUSEUM Macleay Building, Gosper Lane (off Science Road) E NJOY A bumpER T +61 2 9036 5253 F +61 2 9351 5646 E [email protected] WINTER SEASON NICHOLSON MUSEUM In the southern entrance to A WORD FROM THE DIRECTOR the Quadrangle T +61 2 9351 2812 Winter is always a busy time of the his standing in Paris where he worked F +61 2 9351 7305 year with new programs and exhibitions alongside prominent French artists, E [email protected] opening in each of the museums and art including Léger, Kandinsky and Arp. -

MASTER AIA Register of Significant Architecture February2021.Xls AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE of ARCHITECTS REGISTER of SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS in NSW MASTER

AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS REGISTER OF SIGNIFICANT BUILDINGS IN NSW MASTER O A & K HENDERSON / LOUIS A & K HENDERSON OF MELBOURNE, 1935 1940 1991, 1993, T&G Building 555 Dean Street Albury Albury City 4703473Card HENDERSON rear by LOUIS HARRISON 1994, 2006, 2008 H Graeme Gunn Graeme Gunn 1968-69 Baronda (Yencken House) Nelson Lake Road, Nelson Lagoon Mimosa Rocks Bega Valley 4703519 No Card National Park H Roy Grounds Roy Grounds 1964 1980 Penders Haighes Road Mimosa Rocks Bega Valley 4703518 Digital National Park Listing Card CH [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1937 Star of the Sea Catholic 19 Bega Street Tathra Bega Valley 4702325 Card Church G [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1860 1862 Extended 2004 Tathra Wharf & Building Wharf Road Tathra Bega Valley 4702326 Card not located H [architect not identified] [architect not identified] undated Residence Bega Road Wolumla Bega Valley 4702327 Card SC NSW Government Architect NSW Government Architect undated Public School and Residence Bega Road Wolumla Bega Valley 4702328 Card TH [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1911 Bellingen Council Chambers Hyde Street Bellingen Bellingen 4701129 Card P [architect not identified] [architect not identified] 1910 Federal Hotel 77 Hyde Street Bellingen Bellingen 4701131 Card I G. E. MOORE G. E. MOORE 1912 Former Masonic Hall 121 Hyde Street Bellingen Bellingen 4701268 Card H [architect not identified] [architect not identified] circa 1905 Residence 4 Coronation Street Bellingen Bellingen -

Aspects of the Career of Alexander Berry, 1781-1873 Barry John Bridges University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Thesis Collections University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Year Aspects of the career of Alexander Berry, 1781-1873 Barry John Bridges University of Wollongong Bridges, Barry John, Aspects of the career of Alexander Berry, 1781-1873, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Department of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 1992. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1432 This paper is posted at Research Online. 85 Chapter 4 MEMBER OF GENTRY ELITE New South Wales at the time of Berry's and Wollstonecraft's arrival had fluid social and economic structures. Therein lay its attraction for men from the educated lower middle orders of British society with limited means. Charles Nicholson once remarked that one factor making life in the Colony tolerable was the opportunity given to every individual of quality to affect the course of history.1 Few immigrants could boast of their lineage but most aspired to be recognised as gentlemen. As a group they accepted unguestioningly the familiar ideology of the British aristocracy and aimed to form the landed elite of a similarly hierarchical society. They could not replicate that aristocracy's antiquity, wealth, or acceptance, to some extent, of its claims by the rest of society. While as the Rev. Ralph Mansfield testified in 1845: "Nearly all the respectable portion of our community, whatever their legitimate profession . are in some sense farmers and graziers'^ a few colonists could remember when even the oldest of the 'ancient nobility' were landless. The aspirant gentry were 'go getters' on the make and while some had been imbued with notions of leadership, command and social responsiblity during service careers as a group they lacked the British aristocracy's sense of obligation and service.