Download PDF (Inglês)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESEARCH ARTICLE Anti-Glioma Effect of Pseudosynanceia

DOI:10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.7.2295 Effect of Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma Venom on Glioblastoma Cells RESEARCH ARTICLE Editorial Process: Submission:02/14/2021 Acceptance:07/15/2021 Anti-Glioma Effect of Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma Venom on Isolated Mitochondria from Glioblastoma Cells Maral Ramezani, Fatemeh Samiei, Jalal Pourahmad* Abstract Background: Glioblastoma is the most common primary malignant tumor of the central nervous system that occurs in the spinal cord or brain. Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma is a venomous stonefish in the Persian Gulf, which our knowledge about is little. This study’s goal is to investigate the toxicity of stonefish crude venom on mitochondria isolated from U87 cells. Methods: In the first stage, we extracted venom stonefish and then isolated mitochondria have exposed to different concentrations of venom. Finally, mitochondrial toxicity parameters (Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) activity, Reactive oxygen species (ROS), cytochrome c release, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (MMP), and mitochondrial swelling) have evaluated. Results: To determine mitochondrial parameters, we used 115, 230, and 460 µg/ml concentrations. The results of our study show that the venom of stonefish selectively increases upstream parameters of apoptosis such as mitochondrial swelling, cytochrome c release, MMP collapse and ROS. Conclusion: This study suggests that Pseudosynanceia Melanostigma crude venom has selectively caused toxicity by increasing active mitochondrial oxygen radicals. This venom could potentially be a candidate for the treatment of glioblastoma. Keywords: Mitochondria- glioblastoma- fish venoms- cell line- tumor- toxicity-Persian Gulf Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 22 (7), 2295-2302 Introduction freshwater or saltwater. Marine animals most commonly used for animals live in saltwater, i.e. in oceans, seas, Glioblastoma multiform is the most common group of etc. -

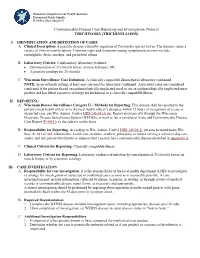

Trichinosis (Trichinellosis) Case Reporting and Investigation Protocol

Wisconsin Department of Health Services Division of Public Health P-01912 (Rev 08/2017) Communicable Disease Case Reporting and Investigation Protocol TRICHINOSIS (TRICHINELLOSIS) I. IDENTIFICATION AND DEFINITION OF CASES A. Clinical Description: A parasitic disease caused by ingestion of Trichinella species larvae. The disease causes a variety of clinical manifestations. Common signs and symptoms among symptomatic persons include eosinophilia, fever, myalgia, and periorbital edema. B. Laboratory Criteria: Confirmatory laboratory evidence: • Demonstration of Trichinella larvae on muscle biopsy, OR • A positive serology for Trichinella. C. Wisconsin Surveillance Case Definition: A clinically compatible illness that is laboratory confirmed. NOTE: In an outbreak setting, at least one case must be laboratory confirmed. Associated cases are considered confirmed if the patient shared an epidemiologically implicated meal or ate an epidemiologically implicated meat product and has either a positive serology for trichinosis or a clinically compatible illness. II. REPORTING A. Wisconsin Disease Surveillance Category II – Methods for Reporting: This disease shall be reported to the patient’s local health officer or to the local health officer’s designee within 72 hours of recognition of a case or suspected case, per Wis. Admin. Code § DHS 145.04 (3) (b). Report electronically through the Wisconsin Electronic Disease Surveillance System (WEDSS), or mail or fax a completed Acute and Communicable Disease Case Report (F-44151) to the address on the form. B. Responsibility for Reporting: According to Wis. Admin. Code § DHS 145.04(1), persons licensed under Wis. Stat. ch. 441 or 448, laboratories, health care facilities, teachers, principals, or nurses serving a school or day care center, and any person who knows or suspects that a person has a communicable disease identified in Appendix A. -

Steering up to the Challenge

Mailed free to requesting homes in Douglas, Northbridge and Uxbridge Vol. V, No. 13 Complimentary to homes by request ONLINE: WWW.BLACKSTONEVALLEYTRIBUNE.COM Friday, January 22, 2016 THIS WEEK’S QUOTE The great “If only life could be a little more bird count tender and art a little more robust.” WEST HILL DAM Alan Rickman PARTICIPATING IN ANNUAL CORNELL EVENT BY GREG BARLOW INSIDE NEWS CORRESPONDENT UXBRIDGE — Be part A2-3 .................LOCAL of a global bird count phe- nomenon on Feb. 14, at A4-5 .............. OPINION 2 p.m. by joining 25-year A7 ............ OBITUARIES Courtesy photos Park Ranger Viola Bramel at West Hill Dam John Ferguson’s fraternity at UMass Dartmouth. A9 ........ SENIOR SCENE at 518 East Hartford Ave. A11 .............. SPORTS in Uxbridge, as a part of Cornell University’s 18th B2 ............. CALENDAR Annual Great Backyard B4 ...........REAL ESTATE Bird Count event. Steering up to Each year for a single B5 .................. LEGALS weekend, Cornell asks people of all demograph- EDITOR’S ics from around the world Greg Barlow photo to explore their back- Viola Bramel and other Park OFFICE HOURS yards, woods, or local Rangers welcome all to the the challenge annual Great Backyard Bird National Parks in search MONDAYS 12-5 of different bird species. Count event at West Hill WEDNESDAYS 1-5 The goal is to track migra- Dam in Uxbridge on Feb. 14. LOCAL COLLEGE STUDENT EMBARKS ON tion patterns and popu- FRIDAYS 1-5 lation density. Cornell TREK FOR CANCER has been researching and in the bird count event. analyzing which birds are Exploring four different LOCAL habitats, the park serves BY GREG BARLOW omore year of high sticking around in specif- NEWS CORRESPONDENT ic areas during the winter as a prime spot to capture school. -

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch Für Europäische Geschichte

Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe European History Yearbook Jahrbuch für Europäische Geschichte Edited by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Volume 20 Dress and Cultural Difference in Early Modern Europe Edited by Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Edited at Leibniz-Institut für Europäische Geschichte by Johannes Paulmann in cooperation with Markus Friedrich and Nick Stargardt Founding Editor: Heinz Duchhardt ISBN 978-3-11-063204-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-063594-2 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-063238-5 ISSN 1616-6485 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 04. International License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number:2019944682 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2019 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published in open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and Binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck Cover image: Eustaţie Altini: Portrait of a woman, 1813–1815 © National Museum of Art, Bucharest www.degruyter.com Contents Cornelia Aust, Denise Klein, and Thomas Weller Introduction 1 Gabriel Guarino “The Antipathy between French and Spaniards”: Dress, Gender, and Identity in the Court Society of Early Modern -

Effectiveness of Neem Oil Upon Pediculosis

EFFECTIVENESS OF NEEM OIL UPON PEDICULOSIS By LINCY ISSAC A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE TAMILNADU DR.M.G.R.MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING MARCH 2011 EFFECTIVENESS OF NEEM OIL UPON PEDICULOSIS Approved by the dissertation committee on :__________________________ Research Guide : __________________________ Dr. Latha Venkatesan M.Sc., (N), M.Phil., Ph.D., Principal and Professor in Nursing Apollo College of Nursing, Chennai -600 095 Clinical Guide : __________________________ Mrs. Shobana Gangadharan M.Sc., (N), Professor Community Health Nursing Apollo College of Nursing, Chennai -600 095. Medical Guide : __________________________ Dr.Mathrubootham Sridhar M.R.C.P.C.H.(Paed)., Consultant –Paediatrician, Apollo Childrens Hospitals, Chennai -600 006 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE TAMILNADU DR.M.G.R.MEDICAL UNIVERSITY, CHENNAI, IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN NURSING MARCH 2011 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the present dissertation entitled “Effectiveness Of Neem Oil Upon Pediculosis” is the outcome of the original research work undertaken and carried out by me, under the guidance of Dr.Latha Venkatesan., M.Sc (N)., M.Phil., Ph.D., Principal and Mrs.Shobana G, M.Sc (N)., Professor, Community Health Nursing, Apollo College Of Nursing, Chennai. I also declare that the material of this has not formed in anyway, the basis for the award of any degree or diploma in this University or any other Universities. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank God Almighty for being with me and guiding me throughout my Endeavour and showering His profuse blessings in each and every step to complete the dissertation. -

Spider Bites

Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Office of Public Health, Louisiana Dept of Health & Hospitals 800-256-2748 (24 hr number) www.infectiousdisease.dhh.louisiana.gov SPIDER BITES Revised 6/13/2007 Epidemiology There are over 3,000 species of spiders native to the United States. Due to fragility or inadequate length of fangs, only a limited number of species are capable of inflicting noticeable wounds on human beings, although several small species of spiders are able to bite humans, but with little or no demonstrable effect. The final determination of etiology of 80% of suspected spider bites in the U.S. is, in fact, an alternate diagnosis. Therefore the perceived risk of spider bites far exceeds actual risk. Tick bites, chemical burns, lesions from poison ivy or oak, cutaneous anthrax, diabetic ulcer, erythema migrans from Lyme disease, erythema from Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, sporotrichosis, Staphylococcus infections, Stephens Johnson syndrome, syphilitic chancre, thromboembolic effects of Leishmaniasis, toxic epidermal necrolyis, shingles, early chicken pox lesions, bites from other arthropods and idiopathic dermal necrosis have all been misdiagnosed as spider bites. Almost all bites from spiders are inflicted by the spider in self defense, when a human inadvertently upsets or invades the spider’s space. Of spiders in the United States capable of biting, only a few are considered dangerous to human beings. Bites from the following species of spiders can result in serious sequelae: Louisiana Office of Public Health – Infectious Disease Epidemiology Section Page 1 of 14 The Brown Recluse: Loxosceles reclusa Photo Courtesy of the Texas Department of State Health Services The most common species associated with medically important spider bites: • Physical characteristics o Length: Approximately 1 inch o Appearance: A violin shaped mark can be visualized on the dorsum (top). -

First Case of Furuncular Myiasis Due to Cordylobia Anthropophaga in A

braz j infect dis 2 0 1 8;2 2(1):70–73 The Brazilian Journal of INFECTIOUS DISEASES www.elsevi er.com/locate/bjid Case report First case of Furuncular Myiasis due to Cordylobia anthropophaga in a Latin American resident returning from Central African Republic a b a c a,∗ Jóse A. Suárez , Argentina Ying , Luis A. Orillac , Israel Cedeno˜ , Néstor Sosa a Gorgas Memorial Institute, City of Panama, Panama b Universidad de Panama, Departamento de Parasitología, City of Panama, Panama c Ministry of Health of Panama, International Health Regulations, Epidemiological Surveillance Points of Entry, City of Panama, Panama a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t 1 Article history: Myiasis is a temporary infection of the skin or other organs with fly larvae. The lar- Received 7 November 2017 vae develop into boil-like lesions. Creeping sensations and pain are usually described by Accepted 22 December 2017 patients. Following the maturation of the larvae, spontaneous exiting and healing is expe- Available online 2 February 2018 rienced. Herein we present a case of a traveler returning from Central African Republic. She does not recall insect bites. She never took off her clothing for recreational bathing, nor did Keywords: she visit any rural areas. The lesions appeared on unexposed skin. The specific diagnosis was performed by morphologic characterization of the larvae, resulting in Cordylobia anthro- Cordylobia anthropophaga Furuncular myiasis pophaga, the dominant form of myiasis in Africa. To our knowledge, this is the first reported Tumbu-fly case of C. -

Onchocerciasis

11 ONCHOCERCIASIS ADRIAN HOPKINS AND BOAKYE A. BOATIN 11.1 INTRODUCTION the infection is actually much reduced and elimination of transmission in some areas has been achieved. Differences Onchocerciasis (or river blindness) is a parasitic disease in the vectors in different regions of Africa, and differences in cause by the filarial worm, Onchocerca volvulus. Man is the the parasite between its savannah and forest forms led to only known animal reservoir. The vector is a small black fly different presentations of the disease in different areas. of the Simulium species. The black fly breeds in well- It is probable that the disease in the Americas was brought oxygenated water and is therefore mostly associated with across from Africa by infected people during the slave trade rivers where there is fast-flowing water, broken up by catar- and found different Simulium flies, but ones still able to acts or vegetation. All populations are exposed if they live transmit the disease (3). Around 500,000 people were at risk near the breeding sites and the clinical signs of the disease in the Americas in 13 different foci, although the disease has are related to the amount of exposure and the length of time recently been eliminated from some of these foci, and there is the population is exposed. In areas of high prevalence first an ambitious target of eliminating the transmission of the signs are in the skin, with chronic itching leading to infection disease in the Americas by 2012. and chronic skin changes. Blindness begins slowly with Host factors may also play a major role in the severe skin increasingly impaired vision often leading to total loss of form of the disease called Sowda, which is found mostly in vision in young adults, in their early thirties, when they northern Sudan and in Yemen. -

WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2014/134709 Al 12 September 2014 (12.09.2014) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 31/05 (2006.01) A61P 31/02 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, (21) International Application Number: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, PCT/CA20 14/000 174 DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (22) International Filing Date: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, 4 March 2014 (04.03.2014) KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (25) Filing Language: English OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (26) Publication Language: English SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, (30) Priority Data: ZW. 13/790,91 1 8 March 2013 (08.03.2013) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (71) Applicant: LABORATOIRE M2 [CA/CA]; 4005-A, rue kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, de la Garlock, Sherbrooke, Quebec J1L 1W9 (CA). GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, (72) Inventors: LEMIRE, Gaetan; 6505, rue de la fougere, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, Sherbrooke, Quebec JIN 3W3 (CA). -

Artrópodos Como Agentes De Enfermedad

DEPARTAMENTO DE PARASITOLOGIA Y MICOLOGIA INVERTEBRADOS, CELOMADOS, CON SEGMENTACIÓN EXTERNA, PATAS Y APÉNDICES ARTICULADOS EXOESQUELETO QUITINOSO TUBO DIGESTIVO COMPLETO, APARATO CIRCULATORIO Y EXCRETOR ABIERTO. RESPIRACIÓN TRAQUEAL EL TIPO INTEGRA LAS CLASES DE IMPORTANCIA MÉDICA COMO AGENTES: ARACHNIDA, INSECTA CHILOPODA DIOCOS, CON FRECUENTE DIMORFISMO SEXUAL CICLOS EVOLUTIVOS DE VARIABLE COMPLEJIDAD (HUEVOS, LARVAS, NINFAS, ADULTOS). INSECTA. CARACTERES GENERALES. LA CLASE INTEGRA CON IMPORTANCIA MEDICA COMO AGENTES: PARÁSITOS, MICROPREDADORES E INOCULADORES DE PONZOÑA. CUERPO DIVIDIDO EN CABEZA, TÓRAX Y ABDOMEN APARATO BUCAL DE DIFERENTE TIPO. RESPIRACIÓN TRAQUEAL TRES PARES DE PATAS PRESENCIA DE ALAS Y ANTENAS METAMORFOSIS DE COMPLEJIDAD VARIABLE ARACHNIDA. CARACTERES GENERALES. LA CLASE INTEGRA CON IMPORTANCIA MEDICA COMO AGENTES ARAÑAS, ESCORPIONES, GARRAPATAS Y ÁCAROS. CUERPO DIVIDIDO EN CEFALOTÓRAX Y ABDOMEN. DIFERENTES TIPOS DE APÉNDICES PREORALES RESPIRACIÓN TRAQUEAL EN LA MAYORÍA CUATRO PARES DE PATAS PRESENCIA DE GLÁNDULA VENENOSAS EN MUCHOS. SIN ALAS Y SIN ANTENAS AGENTE CAUSA O ETIOLOGÍA DIRECTA DE UNA AFECCIÓN. ARTRÓPODOS COMO AGENTES DE ENFERMEDAD: *ARÁCNIDOS (ÁCAROS, ARAÑAS, ESCORPIONES) *MIRIÁPODOS (CIEMPIÉS, ESCOLOPENDRAS) *INSECTOS (PIOJOS, LARVAS DE MOSCAS, ABEJAS, ETC.) TIPOS DE AGENTES NOSOLÓGICOS : - PARÁSITOS (LARVAS O ADULTOS) - MICROPREDADORES - PONZOÑOSOS - ALERGENOS DESARROLLO DE PARASITISMO: - ECTOPARÁSITOS - MIASIS INOCULACIÓN O CONTAMINACIÓN CON PONZOÑAS (TÓXICOS ELABORADOS POR SERES VIVOS). -

Taenia Solium Transmission in a Rural Community in ·Honduras: an Examination of Risk Factors and Knowledge

Taenia solium Transmission in a Rural Community in ·Honduras: An Examination of Risk Factors and Knowledge by Haiyan Pang Faculty of Applied Health Sciences Brock University A thesis submitted for completion of the Master of Science Degree Haiyan Pang © 2004 lAMES A GIBSON LIBRARY . BROCK UNIVERSITY sr. CAtHARINES· ON Abstract Taenia soliurn taeniasis and cysticercosis are recognized as a major public health problem in Latin America. T. soliurn transmission not only affects the health of the individual, but also social and economic development, perpetuating the cycle of poverty. To determine prevalence rates, population knowledge and risk factors associated with transmission, anepidemiological study was undertaken in the rural community of Jalaca. Two standardized questionnaires were used to collect epidemiological and T. soli urn general knowledge data. Kato-Katz technique and an immunoblot assay (EITB) were used to determine taeniasis and seroprevalence, respectively. In total, 139 individuals belonging to 56 households participated in the study. Household characteristics were consistent with conditions of poverty of rural Honduras: 21.4% had no toilet or latrines, 19.6% had earthen floor, and 51.8% lacked indoor tap water. Pigs were raised in 46.4% of households, of which 70% allowed their pigs roaming freely. A human seroprevalence rate of 18.7% and a taeniasis prevalence rate of 2.4% were found. Only four persons answered correctly 2: 6 out of ten T. soliurn knowledge questions, for an average passing score of 2.9%. In general, a serious gap exists in knowledge regarding how humans acquire the infections, especially neurocysticercosis was identified. After regression analysis, the ability to recognize adult tapeworms and awareness of the clinical importance of taeniasis, were found to be significant risk factors for T. -

Lecture 5: Emerging Parasitic Helminths Part 2: Tissue Nematodes

Readings-Nematodes • Ch. 11 (pp. 290, 291-93, 295 [box 11.1], 304 [box 11.2]) • Lecture 5: Emerging Parasitic Ch.14 (p. 375, 367 [table 14.1]) Helminths part 2: Tissue Nematodes Matt Tucker, M.S., MSPH [email protected] HSC4933 Emerging Infectious Diseases HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2 Monsters Inside Me Learning Objectives • Toxocariasis, larva migrans (Toxocara canis, dog hookworm): • Understand how visceral larval migrans, cutaneous larval migrans, and ocular larval migrans can occur Background: • Know basic attributes of tissue nematodes and be able to distinguish http://animal.discovery.com/invertebrates/monsters-inside- these nematodes from each other and also from other types of me/toxocariasis-toxocara-roundworm/ nematodes • Understand life cycles of tissue nematodes, noting similarities and Videos: http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside- significant difference me-toxocariasis.html • Know infective stages, various hosts involved in a particular cycle • Be familiar with diagnostic criteria, epidemiology, pathogenicity, http://animal.discovery.com/videos/monsters-inside-me- &treatment toxocara-parasite.html • Identify locations in world where certain parasites exist • Note drugs (always available) that are used to treat parasites • Describe factors of tissue nematodes that can make them emerging infectious diseases • Be familiar with Dracunculiasis and status of eradication HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 3 HSC4933. Emerging Infectious Diseases 4 Lecture 5: On the Menu Problems with other hookworms • Cutaneous larva migrans or Visceral Tissue Nematodes larva migrans • Hookworms of other animals • Cutaneous Larva Migrans frequently fail to penetrate the human dermis (and beyond). • Visceral Larva Migrans – Ancylostoma braziliense (most common- in Gulf Coast and tropics), • Gnathostoma spp. Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma “creeping eruption” ceylanicum, • Trichinella spiralis • They migrate through the epidermis leaving typical tracks • Dracunculus medinensis • Eosinophilic enteritis-emerging problem in Australia HSC4933.