The Bull of Phalaris and the Historical Method of Diodorus of Sicily

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Epistolae Phalaridis (The Epistles of Phalaris), Latin Translation by FRANCESCO GRIFFOLINI in Latin, Decorated Manuscript on Parchment Italy (Northern?), C

Epistolae Phalaridis (The Epistles of Phalaris), Latin translation by FRANCESCO GRIFFOLINI In Latin, decorated manuscript on parchment Italy (Northern?), c. 1460-1480 iii (modern paper) + 80 + iii (modern paper) folios on parchment, eighteenth- or nineteenth-century foliation in brown ink made before any leaves were removed, 17-88, 97-104, lacking 40 leaves: quires A, B, M, O and P (collation [lacking A-B8] C-L8 [lacking M8] N8 [lacking O-P8]), alphanumerical leaf signatures, Ci, Cii...Niii, Niiii, horizontal catchwords, ruled in brown ink (justification 95 x 57 mm.), written in gray ink in a fine humanistic minuscule in a single column on 16 lines, addressees of letters in red capitals, letter numbers in red in the margins, each letter begins with a very fine 2-line initial in burnished gold on a ground painted in red and blue, highlighted with white penwork, light scribbles in black ink on ff. 40v-41, f. 1 darkened and stained, further stains and signs of use especially in the lower margins at the beginning and the end, edges darkened, but in overall good condition. In modern light brown calf binding, spine almost entirely detached, slightly scratched on the back board. Dimensions 164 x 113 mm. The Italian humanists were fascinated by this collection of fictional letters by the monstrous Sicilian tyrant, Phalaris, famous for torturing his enemies inside a bronze bull and eating human babies. In keeping with the established tradition in Ancient Greece of epistolary fiction, these letters are a literary creation by a yet unknown author, who reinvented Phalaris and explored his public and private life through the fictional letters. -

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

HYPERBOREANS Myth and History in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts Timothy P.Bridgman HYPERBOREANS MYTH and HISTORY in CELTIC-HELLENIC CONTACTS Timothy P.Bridgman

STUDIES IN CLASSICS Edited by Dirk Obbink & Andrew Dyck Oxford University/The University of California, Los Angeles A ROUTLEDGE SERIES STUDIES IN CLASSICS DIRK OBBINK & ANDREW DYCK, General Editors SINGULAR DEDICATIONS Founders and Innovators of Private Cults in Classical Greece Andrea Purvis EMPEDOCLES An Interpretation Simon Trépanier FOR SALVATION’S SAKE Provincial Loyalty, Personal Religion, and Epigraphic Production in the Roman and Late Antique Near East Jason Moralee APHRODITE AND EROS The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology Barbara Breitenberger A LINGUISTIC COMMENTARY ON LIVIUS ANDRONICUS Ivy Livingston RHETORIC IN CICERO’S PRO BALBO Kimberly Anne Barber AMBITIOSA MORS Suicide and the Self in Roman Thought and Literature Timothy Hill ARISTOXENUS OF TARENTUM AND THE BIRTH OF MUSICOLOGY Sophie Gibson HYPERBOREANS Myth and History in Celtic-Hellenic Contacts Timothy P.Bridgman HYPERBOREANS MYTH AND HISTORY IN CELTIC-HELLENIC CONTACTS Timothy P.Bridgman Routledge New York & London Published in 2005 by Routledge 270 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10016 http://www.routledge-ny.com/ Published in Great Britain by Routledge 2 Park Square Milton Park, Abingdon Oxon OX14 4RN http://www.routledge.co.uk/ Copyright © 2005 by Taylor & Francis Group, a Division of T&F Informa. Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photo copying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

AGRIGENTO Introduction Founded in 582 BC by Rhodian and Cretan

AGRIGENTO Introduction Founded in 582 BC by Rhodian and Cretan colonists from nearby Gela, on a site already occupied by Greeks in the 7th century BC, Agrigento (Akragas) was mainly ruled by a succession of tyrants: after Phalaris, in the first half of the 6th century, whose cruelty remained proverbial, by Theron, under whom, allied to the Syracusans, the Agrigentines won the battle against the Carthaginians at Himera, in 480, and his son Thrasydeus who, breaking the alliance with Syracuse, led to the end of his dynasty in 471 BC. In 406 BC, a new conflict with Carthage ended, after a long siege, with the taking and partial destruction of the city, which regained its freedom only thanks to the Corinthian general Timoleon, in 340 BC Contended between Carthaginians and Romans, Agrigento was definitively conquered by the Romans in 210 BC. Flourishing from this date, and until the fall of the Roman Empire, the town gradually became less populated until the 7th century: it was then reduced to a village on the hill of Girgenti (seat of the present town), which was conquered by the Arabs in 829, and later by the Normans in 1086. History The city walls, built in the 6th century BC, enclose an area, considerable for that time, of about 450 hectares, urbanized according to a rigorous orthogonal plan. Protected by the city walls, the sacred buildings of the "Valley of the Temples", all in Doric style, are for the most part arranged at a very regular distance one from the other, for a length of 2 kilometres. -

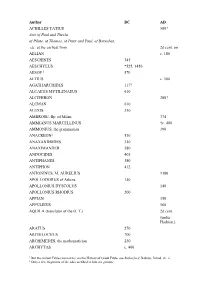

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, Etc

Author BC AD ACHILLES TATIUS 500? Acts of Paul and Thecla, of Pilate, of Thomas, of Peter and Paul, of Barnabas, etc. at the earliest from 2d cent. on AELIAN c. 180 AESCHINES 345 AESCHYLUS *525, †456 AESOP 1 570 AETIUS c. 500 AGATHARCHIDES 117? ALCAEUS MYTILENAEUS 610 ALCIPHRON 200? ALCMAN 610 ALEXIS 350 AMBROSE, Bp. of Milan 374 AMMIANUS MARCELLINUS †c. 400 AMMONIUS, the grammarian 390 ANACREON2 530 ANAXANDRIDES 350 ANAXIMANDER 580 ANDOCIDES 405 ANTIPHANES 380 ANTIPHON 412 ANTONINUS, M. AURELIUS †180 APOLLODORUS of Athens 140 APOLLONIUS DYSCOLUS 140 APOLLONIUS RHODIUS 200 APPIAN 150 APPULEIUS 160 AQUILA (translator of the O. T.) 2d cent. (under Hadrian.) ARATUS 270 ARCHILOCHUS 700 ARCHIMEDES, the mathematician 250 ARCHYTAS c. 400 1 But the current Fables are not his; on the History of Greek Fable, see Rutherford, Babrius, Introd. ch. ii. 2 Only a few fragments of the odes ascribed to him are genuine. ARETAEUS 80? ARISTAENETUS 450? ARISTEAS3 270 ARISTIDES, P. AELIUS 160 ARISTOPHANES *444, †380 ARISTOPHANES, the grammarian 200 ARISTOTLE *384, †322 ARRIAN (pupil and friend of Epictetus) *c. 100 ARTEMIDORUS DALDIANUS (oneirocritica) 160 ATHANASIUS †373 ATHENAEUS, the grammarian 228 ATHENAGORUS of Athens 177? AUGUSTINE, Bp. of Hippo †430 AUSONIUS, DECIMUS MAGNUS †c. 390 BABRIUS (see Rutherford, Babrius, Intr. ch. i.) (some say 50?) c. 225 BARNABAS, Epistle written c. 100? Baruch, Apocryphal Book of c. 75? Basilica, the4 c. 900 BASIL THE GREAT, Bp. of Caesarea †379 BASIL of Seleucia 450 Bel and the Dragon 2nd cent.? BION 200 CAESAR, GAIUS JULIUS †March 15, 44 CALLIMACHUS 260 Canons and Constitutions, Apostolic 3rd and 4th cent. -

The Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, but Having an Important

,1(70 THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES. ftonton: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE, AVE MARIA LANE. ambriDse: DEIGHTON, BELL, AND CO. ltip>ifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS. #tto Hork: MACMILLAX AND CO. THE FRAGMENTS OF ZENO AND CLEANTHES WITH INTRODUCTION AND EXPLANATORY NOTES. AX ESSAY WHICH OBTAINED THE HARE PRIZE IX THE YEAR 1889. BY A. C. PEARSON, M.A. LATE SCHOLAR OF CHRIST S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. LONDON: C. J. CLAY AND SONS, CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE. 1891 [All Rights reserved.] Cambridge : PBIXTKIi BY C. J. CLAY, M.A. AND SONS, AT THK UNIVERSITY PRKSS. PREFACE. S dissertation is published in accordance with thr conditions attached to the Hare Prize, and appears nearly in its original form. For many reasons, however, I should have desired to subject the work to a more under the searching revision than has been practicable circumstances. Indeed, error is especially difficult t<> avoid in dealing with a large body of scattered authorities, a the majority of which can only be consulted in public- library. to be for The obligations, which require acknowledged of Zeno and the present collection of the fragments former are Cleanthes, are both special and general. The Philo- soon disposed of. In the Neue Jahrbticher fur Wellmann an lofjie for 1878, p. 435 foil., published article on Zeno of Citium, which was the first serious of Zeno from that attempt to discriminate the teaching of Wellmann were of the Stoa in general. The omissions of the supplied and the first complete collection fragments of Cleanthes was made by Wachsmuth in two Gottingen I programs published in 187-i LS75 (Commentationes s et II de Zenone Citiensi et Cleaitt/ie Assio). -

Aristotle-Rhetoric.Pdf

Rhetoric Aristotle (Translated by W. Rhys Roberts) Book I 1 Rhetoric is the counterpart of Dialectic. Both alike are con- cerned with such things as come, more or less, within the general ken of all men and belong to no definite science. Accordingly all men make use, more or less, of both; for to a certain extent all men attempt to discuss statements and to maintain them, to defend themselves and to attack others. Ordinary people do this either at random or through practice and from acquired habit. Both ways being possible, the subject can plainly be handled systematically, for it is possible to inquire the reason why some speakers succeed through practice and others spontaneously; and every one will at once agree that such an inquiry is the function of an art. Now, the framers of the current treatises on rhetoric have cons- tructed but a small portion of that art. The modes of persuasion are the only true constituents of the art: everything else is me- rely accessory. These writers, however, say nothing about en- thymemes, which are the substance of rhetorical persuasion, but deal mainly with non-essentials. The arousing of prejudice, pity, anger, and similar emotions has nothing to do with the essential facts, but is merely a personal appeal to the man who is judging the case. Consequently if the rules for trials which are now laid down some states-especially in well-governed states-were applied everywhere, such people would have nothing to say. All men, no doubt, think that the laws should prescribe such rules, but some, as in the court of Areopagus, give practical effect to their thoughts 4 Aristotle and forbid talk about non-essentials. -

Download Image Gallery

AJA IMAGE GALLERY www.ajaonline.org Supplemental Images for “Phalaris: Literary Myth or Historical Reality? Reassessing Archaic Akragas,” by Gianfranco Adornato (AJA 116 [2012] 483–506). * Unless otherwise noted in the figure caption, images are by the author. Image Gallery figures are not edited by AJA to the same level as the published article’s figures. Fig. 1. Map of Akragas (Freeman 1891, 244). Fig. 2. North Ionian Late Wild Goat Style Fig. 3. North Ionian Late Wild Goat Style plate from the Montelusa necropolis. Agri- plate from the Montelusa necropolis. Agri- gento, Museo Archeologico Regionale, inv. gento, Museo Archeologico Regionale, inv. no. S/2254 (© Regione Siciliana, Assessorato no. S/2258 (© Regione Siciliana, Assessorato Regionale dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Regionale dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana; courtesy Museo Archeologico Re- Siciliana; courtesy Museo Archeologico gionale “P. Griffo”) (= fig. 2 [left] in published Regionale “P. Griffo”) (= fig. 2 [right] in pub- article). lished article). Published online July 2012 American Journal of Archaeology 116.3 1 DOI: 10.3764/ajaonline1163.Adornato.suppl AJA IMAGE GALLERY www.ajaonline.org Fig. 4. Plan of the Hellenistic-Roman urban grid (at left are the sacred area of San Nicola, the ekklesiasterion, and the bouleu- terion) (adapted from De Miro 1994, fig. 3). Fig. 5. Drawing of the archaic “casette a schiera” (Marconi 1929a, fig. 17). Fig. 6. Plan of the fortification wall and gates at Akragas (modi- fied from Bennett and Paul 2002, fig. 11). Published online July 2012 American Journal of Archaeology 116.3 2 DOI: 10.3764/ajaonline1163.Adornato.suppl AJA IMAGE GALLERY www.ajaonline.org Fig. -

Acragas (Agrigento) Valley of Temples

Acragas (Agrigento) Valley of Temples Christopher Wood Sitting imperiously on the top of Monte Camico, Agrigento commands enviable views across the broad coastal plain towards the Mediterranean Sea. Led by Aristonous and Pistilus, the Rhodian and Cretan settlers who left Gela in 581BC occupied a perfect site. The high, steep mountain accommodated the town acropolis, while the ridge ringing the town to the south served as natural walls. At the town’s feet was a vast fertile plain, watered by the tranquil rivers Hypsas (mod. Fiume de Sant’Anna) and Acragas (mod. Fiume di San Biagio), from which the ancient city took its name. The colony’s early history followed the common patterns of colonisation. The local Sican people were dispossessed of their land. Relations with Gela were cut and the city instituted its own constitution and government. During his reign, the tyrant Phalaris (ca 570-549BC) extended the town’s territories east to the Licata promontory. In 480BC, Acragas joined its mother-city in defeating the Carthaginians at Himera, further extending its wealth, power and prestige. Its sacking by the Carthaginians in 406BC instigated a period of decline that was not fully arrested until the Roman late Republic period. Acragas (Agrigento) Valley of Temples Page 1 Acragas’ heyday was the fifth century BC, when the city reached its largest size, and a population of ca 200,000 inhabitants. It was also the period of greatest prosperity, based on olive groves, vineyards and horse breeding. The poet Pindar, admiring its magnificent and unique vista of temple architecture, described it as the most beautiful city of antiquity. -

Lucian‟ S Paradoxa: Fiction, Aesthetics, and Identity

i Lucian‟s Paradoxa: Fiction, Aesthetics, and Identity A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by Valentina Popescu BA University of Iasi June 2009 Committee Chair: Kathryn J. Gutzwiller, Professor of Classics Abstract This dissertation represents a novel approach to the Lucianic corpus and studies paradox, with rhetorical, philosophical, and aesthetic implications, as Lucian‟s distinctive discursive mode of constructing cultural identity and literary innovation. While criticizing paradoxography - the literature of wonders - as true discourse, Lucian creates a novel, avowed false, discourse, as a form of contemplation and regeneration of the Greek literary tradition. Paradoxography is Lucian‟s favorite self-referential discourse in prolaliai, rhetorical introductions, where he strives to earn doxa through paradoxa - paradigms of exoticism applied to both author and work. Lucian elevates paradox from exotic to aesthetic, from hybrid novelty to astonishing beauty, expecting his audience to sublimate the experience of ekplexis from bewilderment to aesthetic pleasure. Lucian‟s construction of cultural identity, as an issue of tension between Greek and barbarian and between birthright and paideutic conquest, is predicated on paradoxology, a first- personal discourse based on rhetorical and philosophical paradox. While the biography of the author insinuates itself into the biography of the speaker, Lucian creates tension between macro- text and micro-text. Thus, the text becomes also its opposite and its reading represents almost an aporetic experience. iii iv To my family for their love, sacrifices, and prayers and to the memory of Ion Popescu, Doina Tatiana Mănoiu, and Nicolae Catrina v Table of Contents Introduction 1 1. -

Pythian 1: a Brief Commentary"

" Pythian 1: A Brief Commentary" Emrys Bell-Schlatter Pythian 1: A Brief Commentary Emrys Bell-Schlatter Autumn 2009 Note: Boldface line numbers and Greek words in boldface refer to this ode alone; the line numbers are those assigned by Boeckh. Many thanks go to Gregory Nagy and my fellow students of his Autumn 2009 Pindar seminar for their ongoing discussions and feedback. Line 1. Χρυσέα φόρμιγξ: At the beginning of Olympian 1 (composed in celebration of Hieron’s victory in the chariot race), the phorminx also enters the ode at an early point: ἀλλὰ Δωρίαν ἀπὸ φόρμιγγα πασσάλου | λάμβαν' (Olympian 1.17-18). By directing attention to this instrument here and in Olympian 1, Pindar draws attention also to his persona as an aoidos with the full tradition that the word draws in its train: it is the phorminx that Demodokos, the ‘prototypical epic performer’, removes from a peg at the beginning of the eighth scroll of the Odyssey1 and that accompanies the epic performer as he sings of κλέα ἀνδρῶν (Odyssey viii 73; cf. Iliad IX 186-189, of Achilles singing to his intricately crafted lyre, and the expansion of κλέα ἀνδρῶν to κλέα ἀνδρῶν ἡρώων at Iliad IX 524-525). Thus, by identifying the phorminx and giving it a prominent position in Pythian 1, Pindar also merges the klea that are the theme of the phorminx-singer with the achievements of his subject, a combination especially well-suited to an ode in which Pindar celebrates and conflates the deeds of his subject as a military victor and as an athletic victor.2 A phorminx of gold appears only once elsewhere in literature before Pindar, upon the shield of Herakles in the Hesiodic corpus, and the passage’s contents do not surprise: 1 Odyssey viii 67-69. -

The Academic Questions by M

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Academic Questions by M. T. Cicero This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Academic Questions Author: M. T. Cicero Release Date: June 26, 2009 [Ebook 29247] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ACADEMIC QUESTIONS*** The Academic Questions, Treatise De Finibus. and Tusculan Disputations Of M. T. Cicero With A Sketch of the Greek Philosophers Mentioned by Cicero. Literally Translated by C. D. Yonge, B.A. London: George Bell and Sons York Street Covent Garden Printed by William Clowes and Sons, Stamford Street and Charing Cross. 1875 Contents A Sketch of the Greek Philosophers Mentioned by Cicero.2 Introduction. 35 First Book Of The Academic Questions. 39 Second Book Of The Academic Questions. 59 A Treatise On The Chief Good And Evil. 142 First Book Of The Treatise On The Chief Good And Evil. 144 Second Book Of The Treatise On The Chief Good And Evil. 178 Third Book Of The Treatise On The Chief Good And Evil. 239 Fourth Book Of The Treatise On The Chief Good And Evil. 274 Fifth Book Of The Treatise On The Chief Good And Evil. 311 The Tusculan Disputations. 359 Introduction. 359 Book I. On The Contempt Of Death. 360 Book II. On Bearing Pain. 422 Book III. On Grief Of Mind.