Fern Gazette Vol 18 Part 1 V7.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Taxonomic Revision of Hymenophyllaceae

BLUMEA 51: 221–280 Published on 27 July 2006 http://dx.doi.org/10.3767/000651906X622210 A TAXONOMIC REVISION OF HYMENOPHYLLACEAE ATSUSHI EBIHARA1, 2, JEAN-YVES DUBUISSON3, KUNIO IWATSUKI4, SABINE HENNEQUIN3 & MOTOMI ITO1 SUMMARY A new classification of Hymenophyllaceae, consisting of nine genera (Hymenophyllum, Didymoglos- sum, Crepidomanes, Polyphlebium, Vandenboschia, Abrodictyum, Trichomanes, Cephalomanes and Callistopteris) is proposed. Every genus, subgenus and section chiefly corresponds to the mono- phyletic group elucidated in molecular phylogenetic analyses based on chloroplast sequences. Brief descriptions and keys to the higher taxa are given, and their representative members are enumerated, including some new combinations. Key words: filmy ferns, Hymenophyllaceae, Hymenophyllum, Trichomanes. INTRODUCTION The Hymenophyllaceae, or ‘filmy ferns’, is the largest basal family of leptosporangiate ferns and comprises around 600 species (Iwatsuki, 1990). Members are easily distin- guished by their usually single-cell-thick laminae, and the monophyly of the family has not been questioned. The intrafamilial classification of the family, on the other hand, is highly controversial – several fundamentally different classifications are used by indi- vidual researchers and/or areas. Traditionally, only two genera – Hymenophyllum with bivalved involucres and Trichomanes with tubular involucres – have been recognized in this family. This scheme was expanded by Morton (1968) who hierarchically placed many subgenera, sections and subsections under -

Review of Selected Literature and Epiphyte Classification

--------- -- ---------· 4 CHAPTER 1 REVIEW OF SELECTED LITERATURE AND EPIPHYTE CLASSIFICATION 1.1 Review of Selected, Relevant Literature (p. 5) Several important aspects of epiphyte biology and ecology that are not investigated as part of this work, are reviewed, particularly those published on more. recently. 1.2 Epiphyte Classification and Terminology (p.11) is reviewed and the system used here is outlined and defined. A glossary of terms, as used here, is given. 5 1.1 Review of Selected, Relevant Li.terature Since the main works of Schimper were published (1884, 1888, 1898), particularly Die Epiphytische Vegetation Amerikas (1888), many workers have written on many aspects of epiphyte biology and ecology. Most of these will not be reviewed here because they are not directly relevant to the present study or have been effectively reviewed by others. A few papers that are keys to the earlier literature will be mentioned but most of the review will deal with topics that have not been reviewed separately within the chapters of this project where relevant (i.e. epiphyte classification and terminology, aspects of epiphyte synecology and CAM in the epiphyt~s). Reviewed here are some special problems of epiphytes, particularly water and mineral availability, uptake and cycling, general nutritional strategies and matters related to these. Also, all Australian works of any substance on vascular epiphytes are briefly discussed. some key earlier papers include that of Pessin (1925), an autecology of an epiphytic fern, which investigated a number of factors specifically related to epiphytism; he also reviewed more than 20 papers written from the early 1880 1 s onwards. -

A.N.P.S.A. Fern Study Group Newsletter Number 125

A.N.P.S.A. Fern Study Group Newsletter Number 125 ISSN 1837-008X DATE : February, 2012 LEADER : Peter Bostock, PO Box 402, KENMORE , Qld 4069. Tel. a/h: 07 32026983, mobile: 0421 113 955; email: [email protected] TREASURER : Dan Johnston, 9 Ryhope St, BUDERIM , Qld 4556. Tel 07 5445 6069, mobile: 0429 065 894; email: [email protected] NEWSLETTER EDITOR : Dan Johnston, contact as above. SPORE BANK : Barry White, 34 Noble Way, SUNBURY , Vic. 3429. Tel: 03 9740 2724 email: barry [email protected] From the Editor Peter Hind has contributed an article on the mystery resurrection of Asplenium parvum in his greenhouse. Peter has also provided meeting notes on the reclassification of filmy ferns. From Kylie, we have detail on the identification, life cycle, and treatment of coconut or white fern scale - Pinnaspis aspidistra , which sounds like a nasty problem in the fernery. (Fortunately, I haven’t encountered it.) Thanks also to Dot for her contributions to the Sydney area program and a meeting report and to Barry for his list of his spore bank. The life of Fred Johnston is remembered by Kyrill Taylor. Program for South-east Queensland Region Dan Johnston Sunday, 4 th March, 2012 : Excursion to Upper Tallebudgera Creek. Rendezvous at 9:30am at Martin Sheil Park on Tallebudgera Creek almost under the motorway. UBD reference: Map 60, B16. Use exit 89. Sunday, 1 st April, 2012 : Meet at 9:30am at Claire Shackel’s place, 19 Arafura St, Upper Mt Gravatt. Subject: Fern Propagation. Saturday, 5 th May – Monday, 7th May, 2012. -

Biogeographic Origin, Taxonomic Status, and Conservation Biology of Asplenium Monanthes L

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1-1-2003 Biogeographic origin, taxonomic status, and conservation biology of Asplenium monanthes L. in the southeastern United States Allison Elizabeth Shaw Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Recommended Citation Shaw, Allison Elizabeth, "Biogeographic origin, taxonomic status, and conservation biology of Asplenium monanthes L. in the southeastern United States" (2003). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 20038. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/20038 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Biogeographic origin, taxonomic status, and conservation biology of Asplenium monanthes L. in the southeastern United States by Allison Elizabeth Shaw A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Program of Study Committee: Donald R. Farrar (Major Professor) John D. Nason Fredric J. Janzen Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2003 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the master's thesis of Allison Elizabeth Shaw has met the thesis requirements of Iowa State University Signatures have been redacted for privacy iii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v LIST OF TABLES Vlll ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1 Research questions 1 Thesis organization 2 Taxonomy of Asplenium monanthes 2 Apo gamy 6 Distribution and habitat of Asplenium monanthes 12 Bioclimatic history of the southeastern U.S. -

Universidade Federal Do Paraná Frederico

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARANÁ FREDERICO FREGOLENTE FARACCO MAZZIERO DISTRIBUIÇÃO E DIVERSIDADE DE SAMAMBAIAS E LICÓFITAS EM FORMAÇÕES GEOLÓGICAS DISTINTAS (CALCÁRIO E FILITO), NO PARQUE ESTADUAL TURÍSTICO DO ALTO RIBEIRA, IPORANGA, SÃO PAULO CURITIBA 2013 FREDERICO FREGOLENTE FARACCO MAZZIERO DISTRIBUIÇÃO E DIVERSIDADE DE SAMAMBAIAS E LICÓFITAS EM FORMAÇÕES GEOLÓGICAS DISTINTAS (CALCÁRIO E FILITO), NO PARQUE ESTADUAL TURÍSTICO DO ALTO RIBEIRA, IPORANGA, SÃO PAULO Dissertação apresentada como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre, pelo Programa de Pós-graduação em Botânica do Setor de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal do Paraná. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Paulo H. Labiak CURITIBA 2013 AGRADECIMENTOS Ao Dr. Paulo H. Labiak pela orientação durante estes dois anos. A minha família, sobretudo minha mãe, pelo apoio incondicional. Ao Dr. Mateus L. B. Paciencia por toda ajuda dispendida na elaboração e análises deste trabalho. A Drª. Claudine M. Mynssen pelo auxílio com as espécies de Diplazium. A Drª. Luciana Melo pela ajuda na determinação de algumas espécies do gênero Elaphoglossum. Ao doutorando Fernando Matos pelo auxílio na identificação de espécies de Elaphoglossum. Ao Dr. Pedro B. Schwartsburd pelo auxílio quanto aos gêneros Hypolepis e Saccoloma. Pelo auxílio e companhia em campo: André Soller, Alci Albiero Junior, Mathias Engels, Priscila Tremarin e Eduardo Freire. A Cassio Michelon, Bianca Canestraro e Jovani Pereira pelas proveitosas discussões sobre o fascinante mundo das samambaias e licófitas. Aos colegas de mestrado e laboratório: Alice Gerlach, Alci Abiero Junior, Ana Marcia Charnei, Ana Paula Cardozo, André Soller, Bianca Canestraro, Camila Alves, Carla Royer, Cassio Michelon, Daniela Imig, Duane Fernandes, Emanuela Castro, Fabiano Maia, Jovani Pereira, Lilien Rocha, Luiz Antônio Acra, Márcia Teixeira-Silva, Mathias Engels, Patrícia Luz, Shirley Feuerstein e Suelen Silva. -

Mississippi Natural Heritage Program Special Plants - Tracking List -2018

MISSISSIPPI NATURAL HERITAGE PROGRAM SPECIAL PLANTS - TRACKING LIST -2018- Approximately 3300 species of vascular plants (fern, gymnosperms, and angiosperms), and numerous non-vascular plants may be found in Mississippi. Many of these are quite common. Some, however, are known or suspected to occur in low numbers; these are designated as species of special concern, and are listed below. There are 495 special concern plants, which include 4 non- vascular plants, 28 ferns and fern allies, 4 gymnosperms, and 459 angiosperms 244 dicots and 215 monocots. An additional 100 species are designated “watch” status (see “Special Plants - Watch List”) with the potential of becoming species of special concern and include 2 fern and fern allies, 54 dicots and 44 monocots. This list is designated for the primary purposes of : 1) in environmental assessments, “flagging” of sensitive species that may be negatively affected by proposed actions; 2) determination of protection priorities of natural areas that contain such species; and 3) determination of priorities of inventory and protection for these plants, including the proposed listing of species for federal protection. GLOBAL STATE FEDERAL SPECIES NAME COMMON NAME RANK RANK STATUS BRYOPSIDA Callicladium haldanianum Callicladium Moss G5 SNR Leptobryum pyriforme Leptobryum Moss G5 SNR Rhodobryum roseum Rose Moss G5 S1? Trachyxiphium heteroicum Trachyxiphium Moss G2? S1? EQUISETOPSIDA Equisetum arvense Field Horsetail G5 S1S2 FILICOPSIDA Adiantum capillus-veneris Southern Maidenhair-fern G5 S2 Asplenium -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 127, 1993 23

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 127, 1993 23 RAINFOREST IN EASTERN TASMANIA - FLORISTICS AND CONSERVATION by M.G. Neyland and M.J. Brown (with two tables, four text-figures and one appendix) NEYLAND, M. G. & BROWN, M. J., 1993 (31:viii): Rainforest in eastern Tasmania - floristics and conservation. Pap. Proc. R. Soc. Tasm. 127: 23-32. https://doi.org/10.26749/rstpp.127.23 ISSN 0080-4703. Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment and Land Management, GPO Box 44A, Hobart, Tasmania 7001 (MGN); Forestry Commission, Macquarie Street, Hobart, Tasmania 7000 (MJB). Six floristic communities are described from rainforest in northern and eastern Tasmania. The communities occur in lower rainfall areas, where they are often restricted ro fire-protected sites. They have climatic envelopes which are significantly distinct from each other and from rainforest in higher rainfall areas. The conservation status of the communities is assessed. Key Words: rainforest, Tasmania, conservation, relicts. INTRODUCTION METHODS Temperate rainforests worldwide are restricted mainly to the TASFORHAB profiles (Peters 1984) were collected from coastal and maritime zones, and generally occur in areas of relict rainforest patches throughout the study area. These high rainfall (Kellogg 1992). All the rainforests of Tasmania profiles record the floristics, species abundance and the are relicts of extensive rainforest which once occurred on the structure of the forest. A number of profiles already on the ancient continent Gondwana (Hill 1990, Nelson 1981). TASFORHAB data base were used to cross-check results, Many of the genera which are characteristic of rainforest in and to locate potential rainforest sites. -

A Journal on Taxonomic Botany, Plant Sociology and Ecology Reinwardtia

A JOURNAL ON TAXONOMIC BOTANY, PLANT SOCIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY REINWARDTIA A JOURNAL ON TAXONOMIC BOTANY, PLANT SOCIOLOGY AND ECOLOGY Vol. 13(4): 317 —389, December 20, 2012 Chief Editor Kartini Kramadibrata (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Editors Dedy Darnaedi (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Tukirin Partomihardjo (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Joeni Setijo Rahajoe (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Teguh Triono (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Marlina Ardiyani (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Eizi Suzuki (Kagoshima University, Japan) Jun Wen (Smithsonian Natural History Museum, USA) Managing editor Himmah Rustiami (Herbarium Bogoriense, Indonesia) Secretary Endang Tri Utami Lay out editor Deden Sumirat Hidayat Illustrators Subari Wahyudi Santoso Anne Kusumawaty Reviewers Ed de Vogel (Netherlands), Henk van der Werff (USA), Irawati (Indonesia), Jan F. Veldkamp (Netherlands), Jens G. Rohwer (Denmark), Lauren M. Gardiner (UK), Masahiro Kato (Japan), Marshall D. Sunberg (USA), Martin Callmander (USA), Rugayah (Indonesia), Paul Forster (Australia), Peter Hovenkamp (Netherlands), Ulrich Meve (Germany). Correspondence on editorial matters and subscriptions for Reinwardtia should be addressed to: HERBARIUM BOGORIENSE, BOTANY DIVISION, RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY-LIPI, CIBINONG 16911, INDONESIA E-mail: [email protected] REINWARDTIA Vol 13, No 4, pp: 367 - 377 THE NEW PTERIDOPHYTE CLASSIFICATION AND SEQUENCE EM- PLOYED IN THE HERBARIUM BOGORIENSE (BO) FOR MALESIAN FERNS Received July 19, 2012; accepted September 11, 2012 WITA WARDANI, ARIEF HIDAYAT, DEDY DARNAEDI Herbarium Bogoriense, Botany Division, Research Center for Biology-LIPI, Cibinong Science Center, Jl. Raya Jakarta -Bogor Km. 46, Cibinong 16911, Indonesia. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. WARD AM, W., HIDAYAT, A. & DARNAEDI D. 2012. The new pteridophyte classification and sequence employed in the Herbarium Bogoriense (BO) for Malesian ferns. -

Trichomanes Elongatum

Trichomanes elongatum COMMON NAME Bristle fern SYNONYMS Selenodesmium elongatum (A.Cunn.) Copel., Abrodictyum elongatum (A.Cunn.) Ebihara et K.Iwats. FAMILY Hymenophyllaceae AUTHORITY Trichomanes elongatum A.Cunn. FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON No Long Bay, Coromandel. Photographer: John ENDEMIC GENUS Smith-Dodsworth No ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Ferns NVS CODE TRIELO CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS Long Bay, Coromandel. Photographer: John 2012 | Not Threatened Smith-Dodsworth PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened DISTRIBUTION Endemic. New Zealand: North, South and Chatham Islands. Scarce on the Chatham Islands where it is only known from Rekohu (Chatham Islands) HABITAT Coastal to montane in closed and open forest and gumland scrub. Usually on semi-shaded mossy clay banks, in overhangs on rock, soil, clay or along stream side banks. Often in rather dry or seasonally dry, semi-shaded sites. This species appears to resent poorly drained habitats. FEATURES Terrestrial tufted fern. Rhizomes short, stout, erect, bearing numerous dark brown hairs. Fronds submembranous, ± cartilaginous, dark olive-green, adaxially glossy, surfaces often covered in epiphyllous liverworts and mosses. Stipes 50-200 mm long. Rachises winged only near apices. Laminae 60-150 × deltoid, 3-pinnate. Primary and secondary pinnae overlapping, stalked; ultimate segments broad, deeply toothed, the veins forking several times in each. Sori sessile, borne in notches of lamina segments, several on each primary pinnae. Indusia tubular, mouth slightly flared, receptacle exserted. SIMILAR TAXA Easily recognised by the erect rhizome, deltoid, dark olive-green fronds (which often support epiphyllous bryophytes), and by the conspicuous tubular indusia bearing brown hair-like, bristly well exserted receptacles. -

Epilist 1.0: a Global Checklist of Vascular Epiphytes

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2021 EpiList 1.0: a global checklist of vascular epiphytes Zotz, Gerhard ; Weigelt, Patrick ; Kessler, Michael ; Kreft, Holger ; Taylor, Amanda Abstract: Epiphytes make up roughly 10% of all vascular plant species globally and play important functional roles, especially in tropical forests. However, to date, there is no comprehensive list of vas- cular epiphyte species. Here, we present EpiList 1.0, the first global list of vascular epiphytes based on standardized definitions and taxonomy. We include obligate epiphytes, facultative epiphytes, and hemiepiphytes, as the latter share the vulnerable epiphytic stage as juveniles. Based on 978 references, the checklist includes >31,000 species of 79 plant families. Species names were standardized against World Flora Online for seed plants and against the World Ferns database for lycophytes and ferns. In cases of species missing from these databases, we used other databases (mostly World Checklist of Selected Plant Families). For all species, author names and IDs for World Flora Online entries are provided to facilitate the alignment with other plant databases, and to avoid ambiguities. EpiList 1.0 will be a rich source for synthetic studies in ecology, biogeography, and evolutionary biology as it offers, for the first time, a species‐level overview over all currently known vascular epiphytes. At the same time, the list represents work in progress: species descriptions of epiphytic taxa are ongoing and published life form information in floristic inventories and trait and distribution databases is often incomplete and sometimes evenwrong. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

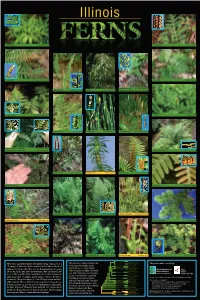

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Roles of Ros Scavenging Enzymes and Aba in Desiccation Tolerance in Ferns

ROLES OF ROS SCAVENGING ENZYMES AND ABA IN DESICCATION TOLERANCE IN FERNS By Kwanele Goodman Wandile Mkhize Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements of Master of Science in the Discipline of Biological Sciences School of Life Sciences College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science University of KwaZulu-Natal Pietermaritzburg Campus South Africa December 2018 Preface The experimental work described in this thesis was carried out by the candidate while based in the Discipline of Biological Sciences School of Life Sciences, of the College of Agriculture, Engineering and Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg campus, under the supervision of Professor Richard P. Beckett, from January 2017 to December 2018. The research was financially supported by the National Research Foundation (South Africa). The contents of this work have not been submitted in any form to another university and, except where the work of others is acknowledged in the text, the results reported are due to investigations by the candidate. __________________________ Signed: Mkhize K.G.W __________________________ Signed: Beckett R.P Date: 30/11/2018 i Declaration 1: Plagiarism I, Kwanele Goodman Wandile Mkhize, student number: 213501630 declare that: (i) The research reported in this dissertation, except where otherwise indicated or acknowledged, is my original work; (ii) This dissertation has not been submitted in full or in part for any degree or examination to any other university; (iii) This dissertation does not contain other persons’ data, pictures, graphs or other information, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other persons; (iv) This dissertation does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers.