Managing Konzo in DRC • Cash for Work in Urban Guinea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title First Name Last (Family) Name Officecountry Jobtitle Organization 1 Mr. Sultan Abou Ali Egypt Professor of Economics

Last (Family) # Title First Name OfficeCountry JobTitle Organization Name 1 Mr. Sultan Abou Ali Egypt Professor of Economics Zagazig University 2 H.E. Maria del Carmen Aceña Guatemala Minister of Education Ministry of Education 3 Mr. Lourdes Adriano Philippines Poverty Reduction Specialist Asian Development Bank (ADB) 4 Mr. Veaceslav Afanasiev Moldova Deputy Minister of Economy Ministry of Economy Faculty of Economics, University of 5 Mr. Saleh Afiff Indonesia Professor Emeritus Indonesia 6 Mr. Tanwir Ali Agha United States Executive Director for Pakistan The World Bank Social Development Secretariat - 7 Mr. Marco A. Aguirre Mexico Information Director SEDESOL Palli Karma Shahayak Foundation 8 Dr. Salehuddin Ahmed Bangladesh Managing Director (PKSF) Member, General Economics Ministry of Planning, Planning 9 Dr. Quazi Mesbahuddin Ahmed Bangladesh Division Commission Asia and Pacific Population Studies 10 Dr. Shirin Ahmed-Nia Iran Head of the Women’s Studies Unit Centre Youth Intern Involved in the 11 Ms. Susan Akoth Kenya PCOYEK program Africa Alliance of YMCA Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 12 Ms. Afrah Al-Ahmadi Yemen Head of Social Protection Unit Social Development Fund Ministry of Policy Development and 13 Ms. Patricia Juliet Alailima Sri Lanka Former Director General Implementation Minister of Labor and Social Affairs and Managing Director of the Socail 14 H.E. Abdulkarim I. Al-Arhabi Yemen Fund for Development Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs 15 Dr. Hamad Al-Bazai Saudi Arabia Deputy Minister Ministry of Finance 16 Mr. Mohammad A. Aldukair Saudi Arabia Advisor Saudi Fund for Development 17 Ms. Rashida Ali Al-Hamdani Yemen Chairperson Women National Committee Head of Programming and Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, 18 Ms. -

Palestinian Rights

DIVISION FOR PALESTINIAN RIGHTS Theme: "The inalienable rights of the Palestinian people" Twenty-third United Nations Seminar on the Question of Palestine (Sixth Asian Regional Seminar) 18 - 22 December 1989 and Third United Nations Asian Regional NGO Symposium on the Question of Palestine 18 - 21 December 1989 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia CONTENTS Paragraph Page . Report of the Twenty-third United Nations Seminar on the Question of Palestine (Sixth Asian Regional Seminar) ................ 1 - 77 ii Introduction .................................. 1 - 4 1 A. Opening statements ........................ 5 - 29 1 B. Panel discussion .......................... 30 - 58 6 C. Conclusions and recommendations ........... 59 - 77 17 11. Report of the Third United Nations Asian Regional NGO Symposium on the Question of Palestine ......................... 78 -109 23 Introduction .................................. 78 - 81 24 A. Declaration adopted by the Third Asian Regional NGO Symposium on the Question of Palestine ................. 82 -100 24 B. Workshop reports .......................... 101 -108 28 C. Asian Co-ordinating Committee for NGOs on the Question of Palestine ......... 109 30 Annexes I. Message from the participants in the Seminar and the NGO Symposium to Mr. Yass.er Arafat, Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Palestine Liberation Organization ...................... 32 11. Motion of thanks ....................................... 33 111. List of participants and observers ..................... 34 I Report of the Twenty-third United Nations Seminar on the Question of Palestine (Sixth Asian Regional Seminar) 18 - 22 December 1989 -1 - Introduction 1. The Twenty-third United Nations Seminar on the Question of Palestine entitled "The inalienable rights of the Palestinian People", (Sixth Asian Regional Seminar), was held jointly with the Third United Nations Asian Regional NGO Symposium at Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, from 18 to 22 December 1989, in accordance with General Assembly resolution 42/66 B of 2 December 1987. -

The Politics of Religious Education, the 2013 Curriculum, and the Public Space of the School

The 2013 Curriculum and The Public Space of the School Report on Religious Life in Indonesia THE POLITICS OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION, THE 2013 CURRICULUM, AND THE PUBLIC SPACE OF THE SCHOOL Suhadi Mohamad Yusuf Marthen Tahun Budi Asyhari Sudarto i The Politics of Religious Education, the 2013 Curriculum, and the Public Space of the School © March 2015 Authors: Suhadi Mohamad Yusuf Marthen Tahun Budi Asyhari Sudarto Editors: Zainal Abidin Bagir Linah K. Pary Translator: Niswatin Faoziah English Editor: Gregory Vanderbilt Cover Design and Layout: Imam Syahirul Alim xiv x 332 halaman; ukuran 15 x 23 cm ISBN: 978-602-72686-1-6 Publishing: Center for Religious and Cross-cultural Studies / CRCS Graduate School, Gadjah Mada University Address: Jl. Teknika Utara,Pogung, Yogyakarta Telp/Fax: 0274 544976 www.crcs.ugm.ac.id; Email:[email protected] The 2013 Curriculum and The Public Space of the School ABBREVIATIONS AGPAII : Association of Indonesian Islamic Education Teachers (Asosiasi Guru Pendidikan Agama Islam Indonesia) BSE : Electronic School Books (Buku Sekolah Elektronik) BSNP : National Education Standards Agency (Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan) CBSA : Student Active Learning (Cara Belajar Siswa Aktif) FGD : Focus Group Discussions G 30 S : September 30th Movement (Gerakan 30 September) HPK : Association of Belief Groups (Himpunan Penghayat Kepercayaan) IAE : International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement IPM : Muhammadiyah Student Association (Ikatan Pelajar Muhammadiyah) IPNU : Nahdlatul Ulama Student Union (Ikatan -

SETTING HISTORY STRAIGHT? INDONESIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY in the NEW ORDER a Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Center for Inte

SETTING HISTORY STRAIGHT? INDONESIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE NEW ORDER A thesis presented to the faculty of the Center for International Studies of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Sony Karsono August 2005 This thesis entitled SETTING HISTORY STRAIGHT? INDONESIAN HISTORIOGRAPHY IN THE NEW ORDER by Sony Karsono has been approved for the Department of Southeast Asian Studies and the Center for International Studies by William H. Frederick Associate Professor of History Josep Rota Director of International Studies KARSONO, SONY. M.A. August 2005. International Studies Setting History Straight? Indonesian Historiography in the New Order (274 pp.) Director of Thesis: William H. Frederick This thesis discusses one central problem: What happened to Indonesian historiography in the New Order (1966-98)? To analyze the problem, the author studies the connections between the major themes in his intellectual autobiography and those in the metahistory of the regime. Proceeding in chronological and thematic manner, the thesis comes in three parts. Part One presents the author’s intellectual autobiography, which illustrates how, as a member of the generation of people who grew up in the New Order, he came into contact with history. Part Two examines the genealogy of and the major issues at stake in the post-New Order controversy over the rectification of history. Part Three ends with several concluding observations. First, the historiographical engineering that the New Order committed was not effective. Second, the regime created the tools for people to criticize itself, which shows that it misunderstood its own society. Third, Indonesian contemporary culture is such that people abhor the idea that there is no single truth. -

Reformist Voices Of

KK K K K K K K K Reformist Voices of KK K K K K K K K KK K K K K K K K Reformist Voices of KK K K K K K K K Mediating Islam K and K Modernity Shireen T. Hunter, editor M.E.Sharpe Armonk, New York London, England Copyright © 2009 by M.E. Sharpe, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher, M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 80 Business Park Drive, Armonk, New York 10504. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reformist voices of Islam : mediating Islam and modernity / edited by Shireen T. Hunter. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7656-2238-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Islam—21st century. 2. Islamic renewal—Islamic countries. 3. Globalization—Religious aspects—Islam. 4. Religious awakening—Islam. 5. Islamic modernism. I. Hunter, Shireen. BP163.R44 2008 297.09'0511—dc22 2008010863 Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z 39.48-1984. ~ BM (c) 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Detailed Table of Contents vii Foreword Vartan Gregorian xv Preface xix Introduction Shireen T. Hunter 3 1. Islamic Reformist Discourse in Iran Proponents and Prospects Shireen T. Hunter 33 2. Reformist and Moderate Voices of Islam in the Arab East Hassan Hanafi 98 3. Reformist Islamic Thinkers in the Maghreb Toward an Islamic Age of Enlightenment? Yahia H. -

Education Reform in Indonesia: Limits of Neoliberalism in a Weak State

EDUCATION REFORM IN INDONESIA: LIMITS OF NEOLIBERALISM IN A WEAK STATE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN SOCIOLOGY MAY 2014 By Sulaiman Mappiasse Dissertation Committee: Hagen Koo, Chairperson Patricia Steinhoff Sun-Ki Chai Hirohisa Saito Barbara Watson Andaya Keywords: Neoliberalism, Education, Reform, Indonesia ABSTRACT This is a study about the recent neoliberal education reform in Indonesia. With the strong support of the people, Indonesia has undertaken a large-scale education reform since the late 1990s. The government was highly confident that this would make Indonesia’s education more efficient and competitive. After more than a decade, however, Indonesia’s education has not significantly improved. Contrary to expectations, the series of policies that was introduced has made Indonesia’s governance less effective and has deepened the existing inequality of educational opportunities. This study examines how and why this reform ended up with these unsatisfactory outcomes. The argument is that Indonesia’s domestic politics and history have interfered with the implementation of the neoliberal policies and led to a distortion of the reform processes. Although neoliberal globalization was a powerful force shaping the process of the reform, domestic conditions played a more important role, especially the weakening of the state’s capacity caused by the crisis that hit Indonesia in 1997/1998. In the process of decentralization, the new configuration of relations between the state, business groups and classes and the emergence of new local leaders brought about unintended consequences. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Penelitian Mengenai Sejarah Pendidikan Pada Masa Orde Baru Sudah Cukup Banyak Dan Berkemban

1 BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Dasar Pemikiran Penelitian mengenai sejarah pendidikan pada masa Orde Baru sudah cukup banyak dan berkembang. Namun, masih sangat sedikit penelitian mengenai Fuad Hassan yang berkaitan dengan kebijakan pendidikan selama menjabat sebagai Menteri Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan pada era orde baru. Padahal jika dilihat kebijakan-kebijakan yang dikeluarkan oleh Fuad Hassan selama menjabat sebagai Menteri Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan berperan besar bagi pendidikan di Indonesia. Penelitian mengenai Fuad Hassan pernah dilakukan oleh Dwi Septiwiharti pada 2009 dalam tesisnya yang berjudul “Tinjauan filsafat atas pemikiran Fuad Hassan tentang Pendidikan”1 yang menjelaskan mengenai konsep pendidikan menurut Fuad Hassan dalam perspektif filsafat. Penelitian tersebut juga mendeskripsikan beberapa struktur penting konsep pendidikan Fuad Hassan dan relevansinya dalam konteks keindonesiaan masa kini. Namun, Penelitian mengenai Kebijakan Pendidikan Masa Menteri Fuad Hassan (1985-1993) belum ada khususnya dalam konteks historis. Penelitian ini penting dilakukan guna mengetahui kebijakan-kebijakan yang dibuat oleh Fuad Hassan dalam bidang pendidikan selama menjabat sebagai Menteri Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan 1 Dwi Septiwiharti, Tinjauan filsafat atas pemikiran Fuad Hassan tentang pendidikan, (Tesis Fakultas Filsafat Universitas Gadjah Mada, 2009) 2 dari 1985 hingga 1993, yang secara historis dapat digunakan untuk menganalisis kebijakan-kebijakan pendidikan di Indonesia baik masa kini dan masa yang akan datang. Tujuan pendidikan disetiap jenjang -

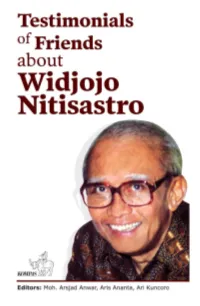

Prof. Dr. Widjojo Nitisastro

Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Law No.19 of 2002 regarding Copyrights Article 2: 1. Copyrights constitute exclusively rights for Author or Copyrights Holder to publish or copy the Creation, which emerge automatically after a creation is published without abridge restrictions according the law which prevails here. Penalties Article 72: 2. Anyone intentionally and without any entitlement referred to Article 2 paragraph (1) or Article 49 paragraph (1) and paragraph (2) is subject to imprisonment of no shorter than 1 month and/or a fine minimal Rp 1.000.000,00 (one million rupiah), or imprisonment of no longer than 7 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 5.000.000.000,00 (five billion rupiah). 3. Anyone intentionally disseminating, displaying, distributing, or selling to the public a creation or a product resulted by a violation of the copyrights referred to under paragraph (1) is subject to imprisonment of no longer than 5 years and/or a fine of no more than Rp 500.000.000,00 (five hundred million rupiah). Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar Aris Ananta Ari Kuncoro Kompas Book Publishing Jakarta, Januari 2008 Testimonials of Friends about Widjojo Nitisastro Publishing by Kompas Book Pusblishing, Jakarta, Januari 2008 PT Kompas Media Nusantara Jalan Palmerah Selatan 26-28, Jakarta 10270 e-mail: [email protected] KMN 70008004 Translated: Harry Bhaskara Editors: Moh. Arsjad Anwar, Aris Ananta, and Ari Kuncoro Copy editors: Gangsar Sambodo and Bagus Dharmawan Cover design by: Gangsar Sambodo and A.N. Rahmawanta Cover foto by: family document All rights reserved. -

The Madrasa in Asia: Political Activism and Transnational Linkages Noor, Farish A

www.ssoar.info The Madrasa in Asia: political activism and transnational linkages Noor, Farish A. (Ed.); Sikand, Yoginder (Ed.); Bruinessen, Martin van (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Sammelwerk / collection Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: OAPEN (Open Access Publishing in European Networks) Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Noor, F. A., Sikand, Y., & Bruinessen, M. v. (Eds.). (2008). The Madrasa in Asia: political activism and transnational linkages (ISIM Series on Contemporary Muslim Societies, 2). Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press. https://nbn- resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-271847 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/deed.de Since the rise of the Taliban and Al Qaeda, the traditional Islamic The Madrasa THE MADRASA IN ASIA schools known as madrasas have frequently been portrayed as hotbeds of terrorism. For much longer, modernisers have denounced POLITICAL ACTIVISM AND madrasas as impediments to social progress, although others have praised them for their self-sufficiency and for providing ‘authentic’ TRANSNATIONAL LINKAGES grassroots education. For numerous poor Muslims in Asia, the madrasa in a still constitutes the only accessible form of education. Madrasa reform sia has been high on the political and social agendas of governments Farish A. Noor, Yoginder Sikand across Asia, but the madrasa itself remains a little understood FARISH FARISH & Martin van Bruinessen (eds.) institution. -

II. BAGIAN KEDUA PEMBICARAAN TINGKAT L/KETERANGAN

II. BAGIAN KEDUA PEMBICARAAN TINGKAT l/KETERANGAN PEMERINTAH ATAS RANCANGAN UNDANG-UNDANG TENTANG PENDIDIKAN NASIONAL 31 PEMBICARAAN TINGKAT I/KETERANGA,N PEMERINTAH ATAS RANCANGAN UNDANG-UNDANG TENT ANG PENDIDIKAN NASIONAL RISALAH RESMI Tahun Sidang 1987/1988 Masa Persidangan IV Rapat Paripuma ke-25 Si fat Terbuka Hari, tanggal Rabu, 29 Juni 1988 Waktu 09.05 s/d 11.40 WIB. Tempat Grahakarana KE TUA Dr. H.J. Naro, S.H., Wakil Ketua Koordinator Bidang Kesejahteraan Rakyat. Sekretaris Benny Wardhanto, S.H., Kepala Biro Persidangan. Acara I. Pembicaraan Tingkat I/Keterangan Pemerintah atas RUU tentang Pendidikan Nasional. 2. Pembicaraan Tingkat IV/Pengambilan Keputus an atas RUU tentang Pengesahan Protocol Amending the Treaty of Amity and Coopera tion in South easi Asia. Pemerintah yang hadir 1. Menteri Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan, Prof. Dr. Fuad Hassan. 2. Menteri Luar Negeri, Ali Alatas, S.H. Anggota yang hadir 370 dari 497 orang Anggota Sidang, ialah: 1. Fraksi Karya Pembangunan. Jumlah Anggota 297, yang hadir.... 207 orang anggota. 2. F raksi ABRI Jumlah anggota 100, yang hadir .... 90 o'rang anggota. 3. Fraksi Persatuan Pembangunan Jumlah anggota 61, yang hadir ..... 51 orang anggota. 4. Fraksi Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Jumlah anggota 39, yang hadir ..... 22 orang Anggota FRAKSIKARYAPEMBANGUNAN: 1. H. MoehammadiyahHaji, S.H,2. Drs. H.M. Diah Ibrahim, 3. Drs. H. Loekman, 4. H. Djamaluddin Tambunan, SH, 5. Drs. H. Bomer Pasaribu, S.H, 6. M.S. Situmorang, S.H, 7. T.A. Lingga, 8. Ir. Abdurachman Rangkuti 9. Drs. Osman Simanjuntak, IO. Drs. Mulatua Pardede, 11. Drs. H. Slamet Riyanto, 12. Ir. Erie Soekardja, 13. -

The National Gallery of Indonesia (GNI): Cultural Policy and Multiculturalism

ICADECS International Conference on Art, Design, Education and Cultural Studies Volume 2020 Conference Paper The National Gallery of Indonesia (GNI): Cultural Policy and Multiculturalism. Study of the “Pameran Seni Rupa Nusantara” 2001-2017 at GNI Citra Smara Dewi and Yuda B Tangkilisan History Department Faculty of Humanities Universitas Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia Abstract This study focuses on the role of the National Gallery of Indonesia (GNI) in maintaining multiculturalism through the policies implemented, namely initiating the activities of the Pameran Seni Rupa Nusantara (PSRN). The PSRN exhibition is one of the GNI’s most important programs because it gives space to the artists of the archipelago - not just Java and Bali - to present works of modern-contemporary art rooted in local wisdom. As a nation that has the characteristics of pluralism, the spirit of multiculturalism in art has become very significant, especially in the middle of the Corresponding Author: Disruption era which is ”full of uncertainty”. Earlier studies have suggested that the Citra Smara Dewi aesthetic concept of Indonesia was based on Indonesian cultural diversity, but these [email protected] studies do not specifically address GNI policies. This article uses qualitative research Received: Month 2020 with a historical method approach together with a material culture analysis approach. Accepted: Month 2020 The results of the study show that GNI as the State Cultural Institute plays an important Published: Month 2020 role in maintaining multiculturalism through exhibition events involving roles and figures. Publishing services provided by Keywords: The National Gallery of Indonesia, Cultural Policy, Pameran Seni Rupa Knowledge E Nusantara, Multiculturalism. Citra Smara Dewi and Yuda B Tangkilisan. -

The Implementation of the 2013 Curriculum and the Issues of English Language Teaching and Learning in Indonesia

The Asian Conference on Language Learning 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan The Implementation of the 2013 Curriculum and the Issues of English Language Teaching and Learning in Indonesia Sahiruddin Universitas Brawijaya, Indonesia 0362 The Asian Conference on Language Learning 2013 Official Conference Proceedings 2013 Abstract The importance of English as world language and the education reform envisaged through several changes in national curriculum play an important role in the development of English language teaching in Indonesia. This paper highlights some constraint and resources related to the implementation of new curriculum 2013 in Indonesia especially in context of English language teaching and learning. Some common ELT problems in Indonesia such as students’ lack of motivation, poor attitude toward language learning, big class size, unqualified teachers, cultural barriers for teachers to adopt new role of facilitator, and so forth are also discussed. However, the current policy of teachers’ sertification program, the integrative topics in some subjects in learning process as one of the main point in new curriculum 2013, and textbook provision as designed on the basis of new curriculum by the Ministry of Education and Culture have brought certain resources to the development of the quality in English language teaching in Indonesia. Some pedagogical concerns for the improvement of language teaching in Indonesia are also suggested. iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org 567 The Asian Conference on Language Learning 2013 Official Conference Proceedings Osaka, Japan Introduction English was the first foreign language obliged to be taught at junior and senior high school as determined by central government policy since independay in 1945.