Christa Wolf's Legacy in Light of the Literature Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction the Surreal Without Surrealism

INTRODUCTION The Surreal without Surrealism The time will come, if it is not already come, when the surrealist enterprise:': will be studied and evaluated, in the history of literature, as an adventure of hope. —Wallace Fowlie, Age of Surrealism Indubitably, Surrealism and the GDR are closely connected, and are more closely related to each other than one might think. When, for example, one listens to the recollections and reads the memoirs of those who lived in this country, apparently no other conclusion can be drawn. Life in the East German Communist state had a surrealistic disposition, was associated with the grotesque, absurd and irrational. Admittedly, Surrealism did not exist in the GDR. Not only are the insights of Hans Magnus Enzensberger and Peter Bürger on the death of the historical avant-garde convincing and applicable to the GDR;1 it is also significant that no German artist or writer who considered him- or herself a Surrealist prior to 1945 returned from exile to settle in the SBZ or the GDR. Most of the celebrities of German Surrealism during the Weimar Republic were forced to go into exile or did not return to Germany at all. Max Ernst, for example, remained living in the USA, and then in 1953 moved to his wife’s old quarters in Paris; Hans Arp decided to live in Switzerland, and in 1949 chose the USA as his home country. Others who had lived through and survived Hitler’s Germany had to face the harsh demands of National Socialist cultural politics that downgraded the avant-garde to the status of Entartete Kunst, or degenerate art, and sidelined and even terrorized its representatives. -

Bert Papenfuß: Tiské

GDR Bulletin Volume 25 Issue 1 Spring Article 23 1998 Bert Papenfuß: Tiské Erk Grimm Columbia University / Barnard College Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Grimm, Erk (1998) "Bert Papenfuß: Tiské," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 25: Iss. 1. https://doi.org/10.4148/ gdrb.v25i0.1265 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. Grimm: Bert Papenfuß: Tiské BOOK REVIEWS as she dismantles her previous world, she is not without Like a work of high modernism, the literary techniques sympathy for the memories she conjures up of her grand• of montage, interior monologue and stream-of-conscious- mother or the Russian children who once lived in her midst. ness, rather than plot, characterize this work. The reader Her demolition plans take on one final target: a large accompanies Krauß on a flight through a dreamscape of sofa soaked to the springs with the sweat of previous genera• impressions of objects, people, and places. In epic-like tions. It is associated with the narrator's grandmother, an fashion Krauß constructs scenes which sometimes burst at early twentieth-century socialist, a woman of strong the seams with thick description, yet always seem light as a character and constitution. Like an animal, the sofa is haiku. The narration often takes on the function of poetry. -

Wolf Biermann, Warte Nicht Auf Bessre Zeiten!

Wolf Biermann, Warte nicht auf bessre Zeiten! Die Autobiographie, Propyläen Verlag, Berlin 2016, 543 S., geb., 28,00 €. Wolf Biermann hat ein großes, ja großartiges Buch geschrieben. Die Autobiografie ist mehr als nur die Selbstsicht des wichtigsten Liedermachers der antistalinistischen Opposition in der SED-Diktatur, sie ist ein Parforce-Ritt durch die deutsch-deutsche Zeitgeschichte. Es beginnt mit der Schilderung des Schicksals und des Widerstands gegen den Nationalsozialismus der kommunistischen Arbeiterfamilie Biermann in Hamburg. Hier werden zwei Konstanten im Leben Wolf Biermanns deutlich: sein bis zum Anfang der 1980er-Jahre reichendes Bekenntnis zum Kommunismus und die Trauer um den jüdischen Vater, der in Auschwitz sein Leben lassen musste. Viele Stationen aus Biermanns Leben waren bis zu dieser Autobiografie öffentlich bereits durch seine zahlreichen Lieder und diese kommentierende Erzählungen bekannt. Sie gewinnen jedoch eine andere emotionale Wucht in der zusammenfassenden Erzählung. Zuerst gilt das für den Überlebenskampf im 1943 verheerend bombardierten Hamburg. Genauso dicht ist die Schilderung des kommunistischen Milieus in der Hansestadt nach der Befreiung vom Nationalsozialismus, das schließlich auch direkt mit seinem Wechsel 1953 in die SED-Diktatur zu tun hatte. Der Schüler Biermann erlebte hier schnell die Verfolgung der Mitglieder der evangelischen Jungen Gemeinde, wandte sich in seiner Internatsschule öffentlich dagegen und sollte trotzdem als Spitzel für die Geheimpolizei geworben werden. Auch hier widerstand er und sein Selbstbewusstsein als Kommunist blieb bei dieser ersten Prüfung »unbeschädigt«. Das ändert sich auch in seiner Zeit in Ost-Berlin als Student an der Humboldt-Universität und als Regie- assistent am Brecht-Theater »Berliner Ensemble« nicht. Hier begann aber das, was Biermann für die ostdeutschen Oppositionellen so wichtig machte, ja Verehrung erzeugte, die bis heute bei vielen anhält. -

Jay Rosellini: Wolf Biermann

GDR Bulletin Volume 19 Issue 1 Spring Article 13 1993 Jay Rosellini: Wolf Biermann Carol Anne Costabile Pennsylvania State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Costabile, Carol Anne (1993) "Jay Rosellini: Wolf Biermann," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 19: Iss. 1. https://doi.org/ 10.4148/gdrb.v19i1.1085 This Review is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. Costabile: Jay Rosellini: Wolf Biermann BOOK REVIEWS 25 in the overnight mobilization of a vast portion of the Rosellini Jay. Wolf Biermann. München: Beck, population previously uncommitted. One senior 1992. 169 pp. history professor and loyal party member talked about attending his first demonstrations in No one was more captivated by the events in East September and October and reported, "I was terribly Germany in 1989 and 1990 than Wolf Biermann. troubled -- all the contradictions I had long carried This enfant terrible of the German-speaking world around with me suddenly surfaced...I simply had to saw the inequities of the East German political expose myself, because I had to stand up in front of system come to an end. But Biermann also saw his my students and tell them what my own position world crumble. Because of Biermann's role in the was." world of pop culture, it is appropriate to re• The final message is sadness. -

GDR Literature in the International Book Market: from Confrontation to Assimilation

GDR Bulletin Volume 16 Issue 2 Fall Article 4 1990 GDR Literature in the International Book Market: From Confrontation to Assimilation Mark W. Rectanus Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Rectanus, Mark W. (1990) "GDR Literature in the International Book Market: From Confrontation to Assimilation," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 16: Iss. 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/gdrb.v16i2.961 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. Rectanus: GDR Literature in the International Book Market: From Confrontati 2 'Gisela Helwig, ed. Die DDR-Gesellschaft im Spiegel ihrer Literatur Günter Grass, Christoph Meckel and Hans Werner Richter). (Köln: Verlag Wissenschaft und Politik, 1986); Irma Hanke, Alltag und However, the socio-critical profile of the "Quarthefte" and his Politik, see note 17 above. commitment to leftist politics soon led to new problems: 22Cf. Wolfgang Emmerich, „Gleichzeitigkeit: Vormoderne, Moderne und Postmoderne in der Literatur der DDR" in: Bestandsaufnahme Das erste Jahr brachte dem Verlag aber auch die ersten Gegenwartsliteratur, 193-211; Bernhard Greiner, „Annäherungen: Schwierigkeiten. Die eine bestand im Boykott der konser• DDR-Literatur als Problem der Literaturwissenschaft" in: Mitteilungen vativen Presse (hauptsächlich wegen der Veröffentlichung des deutschen Germanistenverbandes 30 (1983), 20-36; Anneli Hart• von Stephan Hermlin, dessen Bücher bis dahin von west• mann, „Was heißt heute überhaupt noch DDR-Literatur?" in: Studies in deutschen Verlagen boykottiert worden waren, aber auch GDR Culture and Society 5 (1985), 265-280; Heinrich Mohr, „DDR- wegen der Veröffentlichung von Wolf Biermann). -

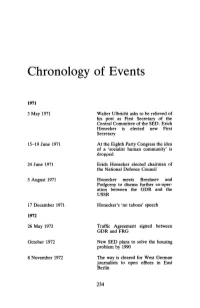

Chronology of Events

Chronology of Events 1971 3 May 1971 Walter Ulbrlcht asks to be relieved of bis post as First Secretary of the Central Committee of the SED. Erlch Honecker is elected new First Secretary 15-19 June 1971 At the Eighth Party Congress the idea of a 'socialist human community' is dropped 24 June 1971 Erlch Honecker elected chairman of the National Defence Council 5 August 1971 Honecker meets Brezhnev and Podgomy to discuss further co-oper ation between the GDR and the USSR 17 December 1971 Honecker's 'no taboos' speech 1972 26 May 1972 Trafik Agreement signed between GDRandFRG October 1972 New SED plans to solve the housing problem by 1990 8 November 1972 The way is cleared for West German journalists to open offices in East Berlin 234 Chronology 0/ Events 235 21 December 1972 Basic Treaty signed as a first step towards 'normalising' relations between GDR and FRG 1973 21 February 1973 A new regulation against foreign journalists slandering the GDR, its institutions and leading figures 1 August 1973 Walter Ulbricht dies at the age of 80 18 September 1973 East and West Germany are accepted as members of the United Nations 2 October 1973 The Central Committee approves a plan to step up the housing programme 1974 1 February 1974 East German citizens are permitted to possess Western currency 20 June 1974 Günter Gaus becomes the first 'Permanent Representative' of the FRG in the GDR 7 October 1974 Law on the revision of the constitution comes into effect. Concept of one German nation is dropped and doser ties with the Soviet Union stressed 1975 1 August 1975 Helsinki Final Act signed 7 October 1975 Treaty of Friendship, Co-operation and Mutual Aid between GDR and Soviet Union 16 December 1975 Spiegel reporter Jörg Mettke expelled after another Spiegel reporter publishes a story on compulsory adop tion in the GDR 1976 29-30 June 1976 Conference of 29 Communist and 236 Chronology 0/ Events Workers' Parties in East Berlin. -

Die Freunde Der Berliner Jahre

Die Freunde der Berliner Jahre Intim Es lag 20 Jahre lang in einem Banksafe: Nun konnte Max Frischs Tagebuch „Berliner Journal“ endlich erscheinen. Eine Lesehilfe Text und Konzeption Andreas Schäfer Beziehungslegende: Uwe Johnson greift das Ehepaar Wolf an, weil unproblematisch es in der DDR geblieben ist (und sich offenbar mit hohem noch wohlfühlt). Frisch will schlichten – Verstrickungsgrad was gar nicht nötig ist. Die Wolfs lassen Johnsons Wut aristokratisch an sich abperlen. hohes Kränkungs- Frisch ist sehr beeindruckt. potenzial Max Frisch im Glück Gerhard und Christa Wolf nachwirkende traumatische Uwe Johnson Die beiden werden wegen ihrer geradezu Freundschaft aus Frischs Mephisto, der kalte Hauch übermenschlichen Souveränität von der Jugend in seinem Nacken. Der engste Vertraute Frisch unendlich bewundert. Stehen des Schweizers, der sich einen diabo- zur DDR und räumen trotzdem Mängel lischen Spaß daraus macht, den Finger ein. Haben Rechtfertigungen nicht Werner Coninx nötig. Klatsch auch nicht. Jammern in dessen Wunde der Verunsicherung Unter hinter allem: die zu stoßen: „Herr Frisch, wir haben den nie, beklagen nur. Auch das noch: ein frühe, fatale Freundschaft offenbar glückliches Ehepaar. Eindruck, Sie leben nicht mehr lang.“ zu dem reichen Werner Coninx, der dem jungen, armen Frisch seine Anzüge vermachte und ihn in die feine Gesellschaft holte. Wolf Biermann In Friedenau Aber ihn später als Autor In Ost-Berlin belächelt hat. Frischs Frisch, tief beeindruckt: „der erste Drama: Erwählung und Freie seit Tagen“. Politisch kaltgestellt, (Selbst-)Verachtung. Also: aber „ein völlig unverschüchterter Die wahren Schriftsteller Mann“. Allerdings verwunderlich, sind immer die anderen. dass bei dem Schriftstellertreffen in Günter Grass Biermanns Wohnung keiner was von Ach, Günter! Frisch ist geradezu Frisch wissen will. -

Staatsbürgerliche Pflichten Grob Verletzt“ Der Rauswurf Des Liedermachers Wolf Biermann 1976 Aus Der DDR „Staatsbürgerliche Pflichten Grob Verletzt“

www.bstu.de „Staatsbürgerliche Pflichten Der Rauswurf des Liedermachers Wolf Biermann 1976 aus der DDR der aus 1976 Biermann Wolf RauswurfDer des Liedermachers grob verletzt“ EINBLICKE IN DAS STASI-UNTERLAGEN-ARCHIV DOKUMENTENHEFT „Staatsbürgerliche Pflichten grob verletzt“ Der Rauswurf des Liedermachers Wolf Biermann 1976 aus der DDR Die vorliegende Auswahl an Dokumenten aus dem Stasi-Unterlagen- Archiv bildet ab, wie sich die Ereignisse in den Stasi-Akten widerspiegeln und nimmt keine weitere Deutung der Quellen vorweg. Die Leserschaft möge den Spielraum zur eigenen Interpretation und persönlichen Auseinandersetzung mit historischen Dokumenten nutzen. Der Verzicht auf eine quellenspezifische Interpretation der nachfolgenden Berichte und Bilder soll den Leserinnen und Lesern ermöglichen, sich selbst einen lebendigen Einblick zu verschaffen. Dieses Dokumentenheft soll damit auch als Anregung dafür dienen, sich mit historischen Einordnungen und weiterführenden Studien zu beschäftigen. Vorwort 4 Die Stasi ist mein Eckermann – von Wolf Biermann 5 Die Geschichte hinter dem Titelbild 7 Inhalt Einführung 8 Der Plan entsteht 12 Bericht über ein abgehörtes Lied von Wolf Biermann 13 Reisesperre gegen Wolf Biermann 15 Vermerk über einen Reiseantrag Biermanns nach Stockholm 16 Konzeption zur Ausbürgerung Biermanns 17 Rechtliche Einschätzung zur Aberkennung der Staatsbürgerschaft 23 Bericht über Biermanns Reaktion auf die Ablehnung eines Reiseantrages 24 Bericht über eine Feier zu Biermanns 38. Geburtstag in seiner Wohnung 26 Kein Interesse am Protest -

The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist

Swiss American Historical Society Review Volume 43 Number 3 Article 3 11-2007 The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist Axel Fair-Schulz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review Part of the European History Commons, and the European Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Fair-Schulz, Axel (2007) "The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist," Swiss American Historical Society Review: Vol. 43 : No. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/sahs_review/vol43/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Swiss American Historical Society Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fair-Schulz: The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist The Impact of Swiss Exile on an East German Critical Marxist by Axel Fair-Schulz Among many East German Marxists, who had embraced Marxism in the 1930s and opted to live in East Germany after World War II (between the 1950s until the end of the GDR in 1989), was a commitment to the Communist party that was informed by a more nuanced and sophisticated Marxism than what most party bureaucrats were exposed to. Among them, for example, the writer Stephan Hermlin as well as the literary scholar Hans Mayer both found their own unique way of accommodating themselves Map showing dividing line to and/or confronting the shortcomings of East between East and West Germany. -

Protest Music, Urban Contexts and Global Perspectives

B. Kutschke: Protest Music, Urban Contexts IRASM 46 (2015) 2: 321-354 and Global Perspectives Beate Kutschke TU Dresden Institut für Kunst- und Musikwissenschaft August-Bebel-Str. 20 01219 Dresden Protest Music, Urban Germany Contexts and Global E-mail: [email protected] UDC: 78.067 Perspectives Original Scholarly Paper Izvorni znanstveni rad Received: February 13, 2015 Primljeno: 13. veljače 2015. Accepted: May 26, 2015 Prihvaćeno: 26. svibnja 2015. Abstract - Résumé This article argues that urban environments in the 1960s and 1970s provided excellent music-cultural and political conditions that stimulated not only protest, but also the crea- I. 1968 – Urbanism and Globalization tion and performance of protest music. It demonstrates this by means of two case studies. The It is evident that urban environments are good music of the Krautrock band CAN in Cologne and the Volks- cradles for protest. Urban environments are marked ambulanz Concert in West by densification and, therefore, offer what protesters Berlin can be considered as emerging from both cities’ and activists need most: the physical presence of unique political and cultural many people – crowds, masses – who express their situations. These were, para- doxically enough, the long-term dissent and forcefully demand change. These densely results of the reorganization of populated urban areas permit the mobilization not Germany after 1945. Both cities possessed lively avant-garde only of protesters, activists, and sympathizers, but music scenes with musicians also journalists and mass media that disseminate the from all over the world, as well as communal grievances that protesters’ message. Furthermore, compact urban triggered protest and protest neighbourhoods compress diverse, heterogeneous music; West Berlin was addi- tionally marked by its specific lifestyles, opinions and value systems opposed to status as a demilitarized zone each other and, thus, catalyze conflicts into protest and immured city. -

Representations of the Staatssicherheitsdienst and Its

Representations of the Staatssicherheitsdienst and its Victims in Christa Wolf’s Was bleibt, Cornelia Schleime’s Weit Fort, Antje Rávic Strubel’s Sturz der Tage in die Nacht, and Hermann Kant’s Kennung Emily C. Bell Advisor: Professor Thomas Nolden, German Studies Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in German Studies April 2013 © 2013 Emily C. Bell Acknowledgements I would like to thank many people for their help and support with this thesis. I wish to express my deep appreciation to Professor Thomas Nolden, my thesis advisor, for his guidance, patience, and dedication throughout this process. Our discussions on this challenging topic and his insightful comments and questions on my numerous drafts have helped shape this thesis. I also want to dearly thank the German Department for their support. In particular, I would like to express my gratitude toward Professor Anjeana Hans who helped me conceive the idea of writing a thesis on the Stasi and Professor Thomas Hansen for reading my first semester draft and giving me useful feedback. I also am grateful for my family and friends for their support, especially Yan An Tan whose friendship was invaluable throughout this process. Table of Contents Introduction 1 I. The Beginnings: the SED and the Stasi II. Representing the Stasi after the Wende III. Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s Das Leben der Anderen IV. The Stasi in Literature Chapter 1: Stasi figures and their victims in Christa Wolf’s Was bleibt 9 I. Introduction II. Fear and Repression in Was bleibt III. Jürgen M. and the Face of Stasi Informants IV. -

Rewriting GDR History: the Christa Wolf Controversy

GDR Bulletin Volume 17 Issue 1 Spring Article 15 1991 Rewriting GDR History: The Christa Wolf Controversy Anna K. Kuhn University of California, Davis Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Kuhn, Anna K. (1991) "Rewriting GDR History: The Christa Wolf Controversy," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 17: Iss. 1. https://doi.org/10.4148/gdrb.v17i1.1088 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact cads@k- state.edu. I have been highly critical of the performanceKuhn: Rewritingof GDR the GDR's History: The Christaso far Wolf contributed. Controversy fledgling democratic movernents.? The point, however, is that to For the very first time, I would argue paradoxical1y, there is now conflate, say, intellectual figures from Btindnis 90 with leading an unparal1eledopportunity for GDR scholars real1yto get down to members of the Writers' Union by bracketing them all as the work. Now that the archives may be opened, historians, intellectuals is to commit a serious error. This is not a backhanded sociologists, and literary critics have their work cut out for them- relapse into the old division between "good" and "bad" Germans provided the historical record can be saved from the rapacious which was promoted here after the Second World War (and grasp of cynical politicians, and the sad legacy of academic acquired something of a life of its own in the sub-genre of GDR apologetics can be worked through and transcended in the spirit of studies), but a plea for methodological clarity, for a more nuanced genuine understanding.