№ 3, 4 03/2014 Issn 2353-4052

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish As

Language Specific Peculiarities Document for Kurmanji Kurdish as Spoken in Turkey 1. Special handling of dialects Kurmanji Kurdish is a major branch of modern Kurdish, which belongs to the Iranian group of languages. Kurdish is largely a spoken language with a limited but growing body of modern literature. There are many dialectal varieties of Kurdish spread over a wide area of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran, Armenia and Azerbaijan. There are, in addition, different classifications of Kurdish languages and Kurdish peoples that align dialectal choice with tribal affinity. Linguistic and Kurdish scholars usually describe modern Kurdish as having two closely related major branches: Kurmanji (the northern branch) and Sorani (the southern branch). They are not mutually intelligible (see Thackston (2006) p. vii). The Kurdish Institute summarizes the situation as follows: “Kurdish has two regional standards, namely Kurmanji in Turkey, and Sorani farther east and south. Roughly half of Kurdish speakers live in Turkey.” (see http://www.institutkurde.org/en/ and also http://www.blueglobetranslations.com/about- kurdish-kurmanji-language.html). Within the larger region there are two other languages often associated with ethnic Kurds. These are Dimili (also known as Zazaki) and Gorani. Although sometimes classified as sub-dialects of Kurdish (e.g., Kurdish Language - Britannica Online Encyclopedia), these languages belong to a different group of Iranian languages (see for example, http://kurds_history.enacademic.com/346/Kurmanji). Although Kurmanji Kurdish is spoken across a range of countries, it has the advantage of being spoken by around 60-80% of Kurds and is considered a regional standard. The majority of Kurmanji speakers live in Turkey, making it the ideal country for collection of audio data (see for example, http://linguakurd.blogfa.com/post-106.aspx). -

Seriously Playful: Philosophy in the Myths of Ovid's Metamorphoses

Seriously Playful: Philosophy in the Myths of Ovid’s Metamorphoses Megan Beasley, B.A. (Hons) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Classics of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities Discipline of Classics and Ancient History 2012 1 2 For my parents 3 4 Abstract This thesis aims to lay to rest arguments about whether Ovid is or is not a philosophical poet in the Metamorphoses. It does so by differentiating between philosophical poets and poetic philosophers; the former write poetry freighted with philosophical discourse while the latter write philosophy in a poetic medium. Ovid, it is argued, should be categorised as a philosophical poet, who infuses philosophical ideas from various schools into the Metamorphoses, producing a poem that, all told, neither expounds nor attacks any given philosophical school, but rather uses philosophy to imbue its constituent myths with greater wit, poignancy and psychological realism. Myth and philosophy are interwoven so intricately that it is impossible to separate them without doing violence to Ovid’s poem. It is not argued here that the Metamorphoses is a fundamentally serious poem which is enhanced, or marred, by occasional playfulness. Nor is it argued that the poem is fundamentally playful with occasional moments of dignity and high seriousness. Rather, the approach taken here assumes that seriousness and playfulness are so closely connected in the Metamorphoses that they are in fact the same thing. Four major myths from the Metamorphoses are studied here, from structurally significant points in the poem. The “Cosmogony” and the “Speech of Pythagoras” at the beginning and end of the poem have long been recognised as drawing on philosophy, and discussion of these two myths forms the beginning and end of the thesis. -

Ez Mafê Xwe Dizanim! I Know My Rights!

Ez mafê xwe dizanim! I know my rights! Manual on human rights education and the right to mother tongue education Based on the experiences of Kurdish youth workers and Kurdish language teachers in Turkey 1 Content Introduction: Berfîn’s story - Memo Şahin .............................................................................................. 6 Berfîn... - Ahmet Altan ...................................................................................................................... 16 Introduction to the Erasmus+-project ................................................................................................... 18 Towards methodological conceptions of minority and language status, policy and rights - Krzysztof Lalik ........................................................................................................................................................ 21 The modern debate on minority and language rights ...................................................................... 22 Language status and policy ............................................................................................................... 29 Language policy ............................................................................................................................. 33 Endangered languages scales ........................................................................................................ 35 Legal protection of minority and language rights ............................................................................ -

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Yazidis and the Original Religion of the Near East | Indistinct Union: Chri

Yazidis and the Original Religion of the Near East | Indistinct Union: Chri... http://indistinctunion.wordpress.com/2007/08/17/yazidis-and-the-original... Indistinct Union: Christianity, Integral Philosophy, and Politics Yazidis and the Original Religion of the Near East The horrific bombing in the Kurdish regions around Kirkuk (death toll estimates currently at 400) targeted the Yazidis, a smallish Kurdish (but non-Muslim) sect. The Ys tended to separate themselves from the Peshmerge (the Kurdish military), which likely resulted in their being left vulnerable to this brutal attack. (For interviews with some Yazidis, here via BBC). Who are theologically the Yazidis ? For repeat readers, they will know I support the (somewhat) controversial thesis of Christian scholar Margaret Barker (known as Royal Temple Theology). Barker’s first work is titled The Older Testament. A brilliant way to describe her point of view–namely that the Judaism that comes across in the Hebrew Bible we currently have has been massively (re)edited, more than most scholars will admit, by the Deuteronomic/Rabbinic schools of Judaism. The Older Testament (as opposed to the “Old Testament” of the Deutro. school) included the belief in two g/Gods. The first was the High God (El, Elyon) who had “sons” (angelic beings). Each angel, known as an angel of the nation, was chosen for a specific people. As above so below. i.e. When their was war on earth between two peoples, their angels were fighting in heaven. Hence all the Psalms rousing YHWH (Israel’s Angel/god) to fight. The second G/god then is YHWH for Israel. -

The Contemporary Roots of Kurdish Nationalism in Iraq

THE CONTEMPORARY ROOTS OF KURDISH NATIONALISM IN IRAQ Introduction Contrary to popular opinion, nationalism is a contemporary phenomenon. Until recently most people primarily identified with and owed their ultimate allegiance to their religion or empire on the macro level or tribe, city, and local region on the micro level. This was all the more so in the Middle East, where the Islamic umma or community existed (1)and the Ottoman Empire prevailed until the end of World War I.(2) Only then did Arab, Turkish, and Iranian nationalism begin to create modern nation- states.(3) In reaction to these new Middle Eastern nationalisms, Kurdish nationalism developed even more recently. The purpose of this article is to analyze this situation. Broadly speaking, there are two main schools of thought on the origins of the nation and nationalism. The primordialists or essentialists argue that the concepts have ancient roots and thus date back to some distant point in history. John Armstrong, for example, argues that nations or nationalities slowly emerged in the premodern period through such processes as symbols, communication, and myth, and thus predate nationalism. Michael M. Gunter* Although he admits that nations are created, he maintains that they existed before the rise of nationalism.(4) Anthony D. Smith KUFA REVIEW: No.2 - Issue 1 - Winter 2013 29 KUFA REVIEW: Academic Journal agrees with the primordialist school when Primordial Kurdish Nationalism he argues that the origins of the nation lie in Most Kurdish nationalists would be the ethnie, which contains such attributes as considered primordialists because they would a mythomoteur or constitutive political myth argue that the origins of their nation and of descent, a shared history and culture, a nationalism reach back into time immemorial. -

Lament of Ahmad Khani: a Study of the Historical Struggle of the Kurds for an Independent Kurdistan

Lament of Ahmad Khani: A Study of the Historical Struggle of the Kurds for an Independent Kurdistan Erik Novak Department of Political Science Villanova University The Kurdish poet Sheikmous Hasan, better known as Cigerxwin, wrote these words as part of his much larger work, Who Am I? while living in exile in Sweden. “I am the proud Kurd, the enemies’ enemy, the friend of peace-loving ones. I am of noble race, not wild as they claim. My mighty ancestors were free people. Like them I want to be free and that is why I fight, for the enemy won’t leave in peace and I don’t want to be forever oppressed.”1 Although Hasan, who died in 1984, was a modern voice for Kurdish nationalism, he is merely one of a chorus of Kurds reaching back centuries crying out for a free and independent Kurdish state, unofficially named Kurdistan. Although the concept of nationalism is common today, the cries of the Kurds for their own state reach back centuries, the first written example coming from the Kurdish poet Ahmad Khani in his national epic Mem-o-Zin in 1695. Mem-o-Zin actually predates the French Revolution of 1789, which is often thought to be the true beginning of the concept of a national state. Despite having conceived of nationalism for the Kurds nearly a century ahead of France and the rest of Western Europe, the Kurds lack a state of their own. What are the origins of Kurdish nationalist thought and how has it evolved over the years? To answer this question, we will track the evolution of Kurdish nationalist thought from its origins during the Ottoman Empire, 1 through World War I and up to the present by looking at the three successor states of the Ottoman Empire that contain the largest Kurdish populations: Turkey, Iran, and Iraq. -

4. Older Olympians.Key

The Older Olympians LVV4U1 - GRADE 12 CLASSICAL CIVILIZATION - MR. A. WITTMANN UNIT 2 – LECTURE 4 1 6 children of Kronos and Rhea are the first Olympians… Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Demeter, Hestia, Hades Aphrodite born of his severed genitals of Uranus 2 God Competence God Competence 1. Zeus Storms 6. Apollo Wisdom 2. Hera Family 7. Artemis Hunt 3. Hestia Hearth 8. Hephaestus Forge 4. Demeter Harvest 9. Athena Knowledge Hades Underworld 10. Ares War 5. Poseidon Sea 11. Hermes Trade 12. Aphrodite Sex 3 Zeus, Lord of the Sky Evolved from Indo-European sky god Dyeus pater (Sky Father) Dyaus pitar (Indian) Dyeus (Iranian) Ju-pitar or Jove (Roman) Tues (Germanic) Sky, high places, thunder/lighting, Bull, eagle, oak, aegis (goat skin) epithets: Nephelegereta (cloud gatherer), Kataibates (descending) 4 5 Zeus, King of Gods & Men Father of all Xenia (guest/host, friendship/ hospitality) Justice, tradition, custom not modern justice heiros gamos sacred marriage with Hera… 1. Uranus + Gaea 2. Kronos + Rhea 3. Zeus + Hera 6 7 Zeus, King of Gods & Men Infidelity with goddess allegorizes the Indo- European male sky god’s triumph over local indigenous female earth goddesses Also illustrates how he organized the natural universe & est. human customs & traditions Metis (cleverness) = Athena (strength and judgment) Themis (established law) = Horae (seasons) Moerae (fates) Eurynomê (Custom) = Eirenê (Peace), Dikê (justice), 3 Graces 8 Zeus, King of Gods & Men Infidelity with mortals explains the origins of heroes & kings Legitimizes local kings and rulering families -

Lucan's Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulf

Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Catherine Connors, Chair Alain Gowing Stephen Hinds Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Classics © Copyright 2014 Laura Zientek University of Washington Abstract Lucan’s Natural Questions: Landscape and Geography in the Bellum Civile Laura Zientek Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Catherine Connors Department of Classics This dissertation is an analysis of the role of landscape and the natural world in Lucan’s Bellum Civile. I investigate digressions and excurses on mountains, rivers, and certain myths associated aetiologically with the land, and demonstrate how Stoic physics and cosmology – in particular the concepts of cosmic (dis)order, collapse, and conflagration – play a role in the way Lucan writes about the landscape in the context of a civil war poem. Building on previous analyses of the Bellum Civile that provide background on its literary context (Ahl, 1976), on Lucan’s poetic technique (Masters, 1992), and on landscape in Roman literature (Spencer, 2010), I approach Lucan’s depiction of the natural world by focusing on the mutual effect of humanity and landscape on each other. Thus, hardships posed by the land against characters like Caesar and Cato, gloomy and threatening atmospheres, and dangerous or unusual weather phenomena all have places in my study. I also explore how Lucan’s landscapes engage with the tropes of the locus amoenus or horridus (Schiesaro, 2006) and elements of the sublime (Day, 2013). -

Vor Sidur 2006 4/10/08 10:04 AM Page 1 1 1 8 6 - 0 7 6 1 N S S I

2-Vor sidur 2. tbl. 2007:Vor sidur 2006 4/10/08 10:04 AM Page 1 1 1 8 6 - 0 7 6 1 N S S I 17. árg. 2. tbl. 2008. Útgefandi: Ásatrúarfélagið, Síðumúla 15, 108 Reykjavík Ritstjóri og ábyrgðarmaður: Egill Baldursson — [email protected] Gleðilegt sumar! Sumardaginn fyrsta þann 24. apríl, hittumst við í Öskjuhlíðinni, á lóðinni okkar, og blótum sumri. Helgistundin hefst kl. 15 og að henni lokinni flytjum við okkur yfir í Síðumúlann þar sem börnin verða í góðu yfirlæti Tóta trúðs. — Börnunum verður boðið í pylsugrill- veislu, þeim gefnar sumargjafir og hoppukastali verður á staðnum. Nú er engin afsökun fyrir því að mæta ekki! Um kl. 19 verður seldur matur á 2.200 kr., en börn undir 12 ára aldri fá frítt. Kvæðamannafélagið Bragi skemmtir gestum. Mikilvægt er að greiða aðgöngumiðana tímanlega inn á reikning félagsins (reikn. 0101-26-011444, kt. 680374-0159) svo hægt sé að panta matinn af einhverri nákvæmni . Einnig verður hægt að kaupa miða við innganginn á 3.000 kr., en fjöldi slíkra miða hlýtur að tak- markast við innkeypt magn matar. Félagsmenn eru hvattir til að fjöl - menna og taka með sér utanfélagsgesti. Góða skemmtun! 1 2-Vor sidur 2. tbl. 2007:Vor sidur 2006 4/10/08 10:04 AM Page 2 Bergþórssaga Fimmtudaginn (Þórsdaginn) 20. mars, í blaðinu 24 Stundir , birtist stutt og athyglis- verð grein um bók, sem gefin var út árið 1950 af tilraunafélaginu Njáll. Í bókinni, er nefnist Bergþórssaga og er sögð skrifuð eftir frásögnum framliðinna, segja persónur úr Njálssögu sína hlið á sögunni, sem er töluvert öðruvísi en sú sem við höfum lesið hingað til. -

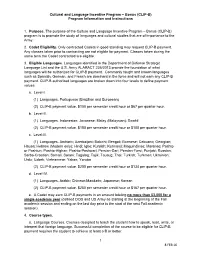

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions

Cultural and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) Program Information and Instructions 1. Purpose. The purpose of the Culture and Language Incentive Program – Bonus (CLIP-B) program is to promote the study of languages and cultural studies that are of importance to the Army. 2. Cadet Eligibility. Only contracted Cadets in good standing may request CLIP-B payment. Any classes taken prior to contracting are not eligible for payment. Classes taken during the same term the Cadet contracted are eligible. 3. Eligible Languages. Languages identified in the Department of Defense Strategic Language List and the U.S. Army ALARACT 236/2013 provide the foundation of what languages will be authorized for CLIP-B payment. Commonly taught and known languages such as Spanish, German, and French are dominant in the force and will not earn any CLIP-B payment. CLIP-B authorized languages are broken down into four levels to define payment values. a. Level-I. (1) Languages. Portuguese (Brazilian and European) (2) CLIP-B payment value. $100 per semester credit hour or $67 per quarter hour. b. Level-II. (1) Languages. Indonesian; Javanese; Malay (Malaysian); Swahil (2) CLIP-B payment value. $150 per semester credit hour or $100 per quarter hour. c. Level-III. (1) Languages. Amharic; Azerbaijani; Baluchi; Bengali; Burmese; Cebuano; Georgian; Hausa; Hebrew (Modern only); Hindi; Igbo; Kurdish; Kurmanji; Maguindinao; Maranao; Pashto or Pashtun; Pashto-Afghan; Pashto-Peshwari; Persian-Dari; Persian-Farsi; Punjabi; Russian; Serbo-Croatian; Somali; Sorani; Tagalog; Tajik; Tausug; Thai; Turkish; Turkmen; Ukrainian; Urdu; Uzbek; Vietnamese; Yakan; Yoruba (2) CLIP-B payment value. $200 per semester credit hour or $134 per quarter hour. -

On Pāzand: Philological Comparison with Pahlavi Hamid Moein a Thesis

On Pāzand: Philological comparison with Pahlavi Hamid Moein A Thesis in the Special Individualized Program Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (SIP - Classics, Language, and Literature) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada August 2012 © Hamid Moein, 2012 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY School of Graduate Studies This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Hamid Moein Entitled: On Pāzand: Philological comparison with Pahlavi. and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (Historical Linguistics) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final Examining Committee: ______________________________ Chair Bradley Nelson _______________________________ Examiner Charles Reiss _______________________________ Examiner Madelyn Kissock _______________________________ Supervisor Mark Hale Approved by _______________________________________________ Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director _______ 2013 _______________________________ Dean of Faculty Table of Contents Abstract.........................................................................................................................................................i Acknowledgement………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….iii List of Pahlavi and Pāzand (Avestan) characters.......................................................................................... iv Introduction to Pāzand