The Balearic Shearwater Puffinus Mauretanicus: a Review of Facts and Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Population Estimates of a Critically Endangered Species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus Mauretanicus , Based on Coastal Migration Counts

Bird Conservation International (2016) 26 :87 –99 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S095927091400032X New population estimates of a critically endangered species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus , based on coastal migration counts GONZALO M. ARROYO , MARÍA MATEOS-RODRÍGUEZ , ANTONIO R. MUÑOZ , ANDRÉS DE LA CRUZ , DAVID CUENCA and ALEJANDRO ONRUBIA Summary The Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is considered one of the most threatened seabirds in the world, with the breeding population thought to be in the range of 2,000–3,200 breeding pairs, from which global population has been inferred as 10,000 to 15,000 birds. To test whether the actual population of Balearic Shearwaters is larger than presently thought, we analysed the data from four land-based census campaigns of Balearic Shearwater post-breeding migration through the Strait of Gibraltar (mid-May to mid-July 2007–2010). The raw results of the counts, covering from 37% to 67% of the daylight time throughout the migratory period, all revealed figures in excess of 12,000 birds, and went up to almost 18,000 in two years. Generalised Additive Models were used to estimate the numbers of birds passing during the time periods in which counts were not undertaken (count gaps), and their associated error. The addition of both counted and esti- mated birds reveals figures of between 23,780 and 26,535 Balearic Shearwaters migrating along the north coast of the Strait of Gibraltar in each of the four years of our study. The effects of several sources of bias suggest a slight potential underestimation in our results. -

Endemic Shearwaters Are Increasing in the Mediterranean in Relation to Factors That Are Closely Related to Human Activities

Global Ecology and Conservation 20 (2019) e00740 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Endemic shearwaters are increasing in the Mediterranean in relation to factors that are closely related to human activities * Beatriz Martín a, , Alejandro Onrubia a, Miguel Ferrer b a Fundacion Migres, CIMA, ctra. N-340, Km.85, Tarifa, E-11380, Cadiz, Spain b Applied Ecology Group, Donana~ Biological Station, CSIC, Seville, Spain article info abstract Article history: The aim of this study was to estimate global population trends of abundance of two Received 20 March 2019 endemic migratory seabird species breeding in the Mediterranean Sea, Balearic and Received in revised form 22 July 2019 Scopoli's shearwaters, from migration counts at the Strait of Gibraltar. Specifically, we Accepted 31 July 2019 assessed how regional environmental conditions (i.e. sea surface temperature, chlorophyll a concentration, NAO index and fish catches), as proxies of climate change, prey availability Keywords: and human-induced mortality factors, modulate the interannual variation in shearwater Chlorophyll numbers. The change in the migratory population size of both shearwater species was Climate change fi Fisheries estimated by tting Generalized Additive Models (GAM) to the annual counts against the fi Seabird year of observation. Speci cally, we modelled daily counts of migrant shearwaters during Monitoring the post-breeding season. Contrary to current estimates at breeding colonies, coastal-land based counts of migrating birds provide evidence that Baleric and Scopoli's shearwaters have been recently increasing in the Mediterranean Sea. Our results highlight that de- mographic patterns in these species are complex and non-linear, suggesting that most of the increases have happened recently and intimately bounded to environmental factors, such as chlorophyll concentration and fisheries, that are closely related to human activ- ities. -

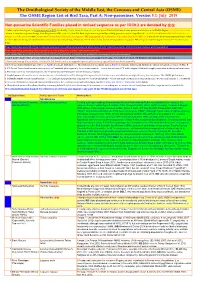

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

Tracking, Feather Moult and Stable Isotopes Reveal Foraging Behaviour

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2017) 23, 130–145 BIODIVERSITY Tracking, feather moult and stable RESEARCH isotopes reveal foraging behaviour of a critically endangered seabird during the non-breeding season Rhiannon E. Meier1*, Stephen C. Votier2, Russell B. Wynn1, Tim Guilford3, Miguel McMinn Grive4, Ana Rodrıguez5, Jason Newton6, Louise Maurice7, Tiphaine Chouvelon8,9, Aurelie Dessier8 and Clive N. Trueman10 1National Oceanography Centre, European ABSTRACT Way, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK, Aim The movement patterns of marine top predators are likely to reflect 2Environment and Sustainability Institute, responses to prey distributions, which themselves can be influenced by factors University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9FE, UK, 3Animal such as climate and fisheries. The critically endangered Balearic shearwater Behaviour Research Group, Department of Puffinus mauretanicus has shown a recent northwards shift in non-breeding dis- Zoology, University of Oxford, The tribution, tentatively linked to changing forage fish distribution and/or fisheries A Journal of Conservation Biogeography Tinbergen Building, South Parks Road, activity. Here, we provide the first information on the foraging ecology of this Oxford OX1 3PS, UK, 4Biogeografia, species during the non-breeding period. geodinamica i sedimentaciodela Location Breeding grounds in Mallorca, Spain, and non-breeding areas in the Mediterrania occidental (BIOGEOMED), north-east Atlantic and western Mediterranean. Universitat de les Illes Balears, Cra. de Valldemossa, km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Illes Methods Birdborne geolocation was used to identify non-breeding grounds. Balears, Spain, 5Balearic Shearwater Information on feather moult (from digital images) and stable isotopes (of Conservation Association, Puig del Teide 4 - both primary wing feathers and potential prey items) was combined to infer 315, Palmanova 07181, Illes Balears, Spain, foraging behaviour during the non-breeding season. -

What Genetics Tell Us About the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Balearic Shearwater?

BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION 137 (2007) 283– 293 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon What genetics tell us about the conservation of the critically endangered Balearic Shearwater? Meritxell Genovarta,b,*, Daniel Oroa, Javier Justec, Giorgio Bertorelleb aInstitut Mediterrani d’Estudis Avanc¸ats IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), Miquel Marque`s 21, 07190 Esporles, Mallorca, Spain bDipartimento di Biologia, Universita` di Ferrara, Via Borsari 46, 44100 Ferrara, Italy cEstacio´n Biolo´gica de Don˜ ana (CSIC), Avda. Ma Luisa s/n, Aptdo. 41080 Sevilla, Spain ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is one of the most critically endangered sea- Received 20 March 2006 birds in the world. The species is endemic to the Balearic archipelago, and conservation Received in revised form concerns are the low number of breeding pairs, the low adult survival, and the possible 5 February 2007 hybridization with a sibling species, the morphologically smaller Yelkouan shearwater (P. Accepted 18 February 2007 yelkouan). We sampled almost the entire breeding range of the species and analyzed the genetic variation at two mitochondrial DNA regions. No genetic evidence of population decline was found. Despite the observed philopatry, we detected a weak population struc- Keywords: ture mainly due to connectivity among colonies higher than expected, but also to a Pleis- Conservation genetics tocene demographic expansion. Some colonies showed a high imbalance between Introgression immigration and emigration rates, suggesting spatial heterogeneity in patch quality. Population expansion Genetic evidence of maternal introgression from the sibling species was reinforced, but Population structure almost only in a peripheral colony and not followed, at least to date, by the spread of the Puffinus mauretanicus introgressed mtDNA lineages. -

Balearic Islands Area

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Title/Name of the area: Balearic Islands Area Presented by: Greenpeace International as a submission to the Mediterranean Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs), 7 to 11 April 2014, Málaga, Spain. Contact person: Sofia Tsenikli, Senior Political Advisor, Email: [email protected]; tel: +30 6979443306 Information in this submission has been presented at the CBD Expert Workshop on Scientific and Technical Guidance on the use of Biogeographic Classification Systems and Identification of Marine Areas beyond national jurisdiction in need of protection, 29 September - 2 October 2009, in Ottawa, Canada, and is included in the official report of the workshop which can be accessed here. Abstract The Balearic Archipelago is one of the richest European regions in terms of marine animal species diversity and is characterized by a wide range of ecosystem types (e.g. maërl beds, Leptometra beds, soft red algae communities, Posidonia meadows, etc) (Aguilar et al.,2007b) . Some of these communities are considered rare on a European scale. The area’s complex oceanography results in high levels of productivity, reflected by its importance as a feeding ground for a wide range of species, including fin and sperm whales, loggerhead turtles and as a crucial spawning ground for threatened Bluefin tuna. The area is also an important breeding ground for the endemic Balearic shearwater. Introduction In 2006 Greenpeace published a proposal for a regional network of large-scale marine reserves with the aim of protecting the full spectrum of life in the Mediterranean (see Figure 1) (Greenpeace 2006). -

Summary of Evidence of Aggregations of Balearic Shearwaters in the UK up to 2013

JNCC Report No. 642 Summary of evidence of aggregations of Balearic shearwaters in the UK up to 2013 Parsons. M.a, Bingham, C.b, Allcock, Z.c & Kuepfer, A.d November 2019 © JNCC, Peterborough 2019 ISSN 0963-8091 For further information please contact: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY www.jncc.gov.uk This report should be cited as: Parsons, M., Bingham, C., Allcock, Z. & Kuepfer, A. 2019. Summary of evidence of aggregations of Balearic shearwaters in the UK up to 2013. JNCC Report No. 642, JNCC, Peterborough, ISSN 0963-8091. EQA: This report is compliant with the JNCC Evidence Quality Assurance Policy https://jncc.gov.uk/about-jncc/corporate-information/evidence-quality-assurance/. Affiliations: a JNCC – Inverdee House, Baxter Street, Aberdeen, AB11 9QA b RSPB North Scotland Office - Etive House, Beechwood Park, Inverness, IV2 3BW c Marine Scotland Science - 375 Victoria Road, Aberdeen, AB11 9DB d SAERI - Stanley Cottage North, Ross Road, Stanley, FIQQ 1ZZ, Falkland Islands Summary Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is listed on Annex I of the EU Birds Directive (2009/147/EC). The EU Birds Directive requires Member States to classify Special Protection Areas (SPA) for birds listed on Annex I of the Directive and for regularly occurring migratory species. Balearic shearwater breeds solely in the western Mediterranean, numbering some 3000 pairs; it is listed by IUCN as Critically Endangered. Movements after the breeding season bring birds into Atlantic waters, primarily off Iberia and western France but also into UK waters, especially those of the English Channel during June to October. -

Balearic Shearwater: Species Information for Marine Special Protection Area Consultations

Natural England Technical Information Note TIN144 Balearic shearwater: species information for marine Special Protection Area consultations The UK government has committed to identifying a network of Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in the marine environment by 2015. Natural England is responsible for recommending SPAs in English waters to Defra for classification. This and other related information notes have been prepared and will be available at meetings and online so that anyone who might be interested in why the SPA is being considered for classification can find out more about the birds that may be protected. For more information about the process for establishing marine SPAs see TIN120 Establishing Marine Special Protection Areas. Background The Birds Directive (EC Directive on the conservation of wild birds (2009/147/EC) requires member states to identify SPAs for: rare or vulnerable bird species (as listed in Annex I of the Directive); and regularly occurring migratory bird species. The Balearic shearwater, Puffinus mauretanicus, is listed under Annex I of the Birds Directive. Also known as the Mediterranean shearwater, it Balearic shearwater © Tom Brereton is between 34 and 38 cm long with a wingspan of 83-93 cm1. There is little information available Distribution and population on the lifespan of this species. This species breeds exclusively on a small number of the Balearic islands in the Conservation status Mediterranean Sea, dispersing into the Atlantic IUCN red-listed as critically endangered2 due following the breeding season, including into UK 5 to a rapid population decline; waters . SPEC1 (species of global conservation concern)3; UK population listed in Annex 1 of EU Birds Directive (rare The global breeding population was only 3,193 and vulnerable species); and pairs in 2009, although non-breeding surveys UK red-listed bird of conservation concern4. -

Balearic Shearwater

Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus Pardela Balear Puffin des Baléares CRITICALLY ENDANGERED ENDANGERED VULNERABLE NEAR THREATENED LEAST CONCERN NOT LISTED TAXONOMY Order Procellariiformes Family Procellariidae Genus Puffinus Species P. mauretanicus (Lowe, 1921) In ornithological literature, the Balearic Shearwater was traditionally regarded as a subspecies of the Manx Photo © Pep Arcos Shearwater Puffinus puffinus [1, 2, 3, 4] and, later on, of the Yelkouan CONSERVATION LISTINGS AND PLANS Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan [5, 6]. However, enough evidence International accumulated by the 1990s to . 2012 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species – Critically Endangered (since 2004) [15, 16] recommend its consideration as a . Bonn Convention on Migratory Species (Appendix I and Resolution distinct species based on differences in 8.29) [17, 18] morphology, genetics, behaviour and . European Union Council Directive 2009/147/EC on the conservation of ecology [7, 8, 9]. This is the current view wild birds [19] of the scientific and conservation . European Union Council Directive 92/43/EEC (Habitats Directive) [20] communities. Recently, the genetics of . BirdLife International Species Action Plan [21, 22]. Puffinus mauretanicus have again . Barcelona Convention on the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea (Appendix II and Action Plan) [23] received attention due to concerns . OSPAR Convention for the protection of the marine environment of the about possible hybridization with the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR List of endangered and/or in decline sympatrically breeding P. yelkouan [10, species and habitats) [24] 11, 12, 13, 14]. However, Genovart et al. Bern Convention – Protected Fauna (Appendix II) [25, 26] (2012) conclude that although the introgression of P. yelkouan breeding in Spain P. -

Modelling Demography and Extinction Risk in the Endangered Balearic Shearwater

Biological Conservation 116 (2004) 93–102 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Modelling demography and extinction risk in the endangered Balearic shearwater Daniel Oroa,*, Juan Salvador Aguilarb,c,1, Jose´ Manuel Iguala, Maite Louzaoa aInstitut Mediterrani d’Estudis Avanc¸ ats IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), Miquel Marques 21, 07190 Esporles, Mallorca, Spain bDireccio´ General de Biodiversitat, Govern Balear, Gabriel Alomar i Villalonga, 33 07006 Palma, Mallorca, Spain cSEO/BirdLife, Melquı´ades Biencinto 34, 28053 Madrid, Spain Received 10 December 2002; received in revised form 11 March 2003; accepted 10 April 2003 Abstract Several demographic parameters of Balearic shearwater (Puffinus mauretanicus) were estimated and used to model extinction probabilities for the species, which is an endemic seabird confined to a Mediterranean archipelago. Adult survival was analyzed through capture–recapture models at two colonies free of adult predators during 1997–2002. Extinction probabilities for the world breeding population were modelled using Monte Carlo simulations of population trajectories, introducing stochasticity both demographic and environmental. Adult survival estimate (0.780, SE=0.020, 95% Confidence Intervals: 0.739–0.816) was unusually low for a Procellariiform, suggesting that sources of mortality other than predators (e.g. fishing gears) also occur. A deterministic model showed a declining trend for the world breeding population (l=0.952), and significantly less than 1. Population viability analysis showed that in the presence of environmental and demographic stochasticities, mean extinction time for the world popu- lation was estimated at 40.4 years (SE=0.2), and mean growth rate showed a 7.4% decrease per year. Demographic stochasticity played a more important role than environmental stochasticity in population growth rate. -

Conservation Biology of the Critically Endangered Balearic Shearwater Puffinus Mauretanicus: Bridging the Gaps Between Breeding Colonies and Marine Foraging Grounds

Conservation biology of the critically endangered Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus: bridging the gaps between breeding colonies and marine foraging grounds Maite Louzao Arsuaga Tesi Doctoral Programa de Ciències Marines IMEDEA Setembre 2006 TESI DOCTORAL Conservation biology of the critically endangered Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus: bridging the gaps between breeding colonies and marine foraging grounds Memòria presentada per Maite Louzao Arsuaga per optar al títol de Doctora del Programa de Doctorat de Ciències Marines del IMEDEA, Universitat de les Illes Balears, sota la direcció dels Drs. Daniel Oro de Rivas i José Manuel Arcos Pros, i ponència del Dr. Rafael Bosch Zaragoza. Maite Louzao Arsuaga Palma, 4 de setembre 2006 ViP ViP ViP El director/tutor de la tesi El director de la tesi El ponent de la tesi Dr. Daniel Oro de Rivas Dr. José Manuel Arcos Pros Dr. Rafael Bosch Zaragoza IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB) IBSL, University of Glasgow Universitat de les Illes Balears SEO/BirdLife Gurasoei Contenidos Contenidos Eskerrak, agradecementos, agraïments………………………………………………… iii Capítulo 1 Introducción...…………..……………………………..…………………. 1 Section I. Conservation at the breeding colonies………………………………......... 39 Chapter 2 Modelling demography and extinction risk in the endangered Balearic shearwater……………………………..……………………….. 41 Chapter 3 Small pelagic fish, trawling discards and breeding performance of the critically endangered Balearic Shearwater: improving conservation diagnosis……………………………..…………………… 65 Chapter 4 Inter-population variation in egg size of an endangered Procellariiform: interplay between body size and feeding ecology……………………………..……………………………………... 87 Section II. Conservation at the marine foraging grounds………………………….. 109 Chapter 5 Oceanographic habitat of an endangered Mediterranean Procellariiform: implications for marine protected areas……………………………..……………………………………….. 111 Chapter 6 Seabird attendance to the trawling fishery at the Balearic archipelago (western Mediterranean) ………………………………… 145 Conclusiones……………………………..……………………………..…………………. -

The Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus (Puffinus?) Yelkouan W

The Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus (puffinus?) yelkouan W. R. P. Bourne, E.J. Mackrill, A. M. Paterson and P. Yesou n the classical Greek period, 2,500 years ago, two seabirds had Ialready given rise to immortal legends in the eastern Mediterranean. The Siren was reputed to lure seafarers to their doom by singing upon outlying rocks, a habit found in a variety of marine animals, but particularly characteristic of petrels on misty nights. The larger species of the area in particular, once known as the Mediterranean Shearwater and now as Cory's Shearwater, which still bears the local vernacular name Diomedee and scientific name Calonectris diomedea in memory of one of the Greeks who besieged Troy (Winthrope 1973), has a voice very like a foghorn. In contrast, the Halcyon was equally celebrated because it was never seen ashore, and thought to reproduce upon the surface of the sea in calm weather, which was named after it. This seems equally characteristic of a smaller species, long known as the Levantine Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan until it was reclassified early in this century as a race of the Manx Shearwater P. puffinus yelkouan, since it does not fly so well, and is prone to settle in flocks on the water far from its island breeding-places when the wind falls. Although the identity of these birds was forgotten over the years, and they were eventually considered to be all sorts of strange things, such as Gannets Sula bassana and Kingfishers Alcedo atthis (Yapp 1987), Win thrope (1973) reported that the name Halcyon is still used for the 'Levantine Shearwater' in its area of origin.