The Yelkouan Shearwater Puffinus (Puffinus?) Yelkouan W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Population Estimates of a Critically Endangered Species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus Mauretanicus , Based on Coastal Migration Counts

Bird Conservation International (2016) 26 :87 –99 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S095927091400032X New population estimates of a critically endangered species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus , based on coastal migration counts GONZALO M. ARROYO , MARÍA MATEOS-RODRÍGUEZ , ANTONIO R. MUÑOZ , ANDRÉS DE LA CRUZ , DAVID CUENCA and ALEJANDRO ONRUBIA Summary The Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is considered one of the most threatened seabirds in the world, with the breeding population thought to be in the range of 2,000–3,200 breeding pairs, from which global population has been inferred as 10,000 to 15,000 birds. To test whether the actual population of Balearic Shearwaters is larger than presently thought, we analysed the data from four land-based census campaigns of Balearic Shearwater post-breeding migration through the Strait of Gibraltar (mid-May to mid-July 2007–2010). The raw results of the counts, covering from 37% to 67% of the daylight time throughout the migratory period, all revealed figures in excess of 12,000 birds, and went up to almost 18,000 in two years. Generalised Additive Models were used to estimate the numbers of birds passing during the time periods in which counts were not undertaken (count gaps), and their associated error. The addition of both counted and esti- mated birds reveals figures of between 23,780 and 26,535 Balearic Shearwaters migrating along the north coast of the Strait of Gibraltar in each of the four years of our study. The effects of several sources of bias suggest a slight potential underestimation in our results. -

Acoustic Attraction of Grey-Faced Petrels (Pterodroma Macroptera Gouldi) and Fluttering Shearwaters (Puffinus Gavia) to Young Nick’S Head, New Zealand

166 Notornis, 2010, Vol. 57: 166-168 0029-4470 © The Ornithological Society of New Zealand, Inc. SHORT NOTE Acoustic attraction of grey-faced petrels (Pterodroma macroptera gouldi) and fluttering shearwaters (Puffinus gavia) to Young Nick’s Head, New Zealand STEVE L. SAWYER* Ecoworks NZ Ltd, 369 Wharerata Road, RD1, Gisborne 4071, New Zealand SALLY R. FOGLE Ecoworks NZ Ltd, 369 Wharerata Road, RD1, Gisborne 4071, New Zealand Burrow-nesting and surface-nesting petrels colonies at sites following extirpation or at novel (Families Procellariidae, Hydrobatidae and nesting habitats, as the attraction of prospecting Oceanitidae) in New Zealand have been severely non-breeders to a novel site is unlikely and the affected by human colonisation, especially through probabilities of recolonisation further decrease the introduction of new predators (Taylor 2000). as the remaining populations diminish (Gummer Of the 41 extant species of petrel, shearwater 2003). and storm petrels in New Zealand, 35 species are Both active (translocation) and passive (social categorised as ‘threatened’ or ‘at risk’ with 3 species attraction) methods have been used in attempts to listed as nationally critical (Miskelly et al. 2008). establish or restore petrel colonies (e.g. Miskelly In conjunction with habitat protection, habitat & Taylor 2004; Podolsky & Kress 1992). Methods enhancement and predator control, the restoration for the translocation of petrel chicks to new colony of historic colonies or the attraction of petrels to sites are now fairly well established, with fledging new sites is recognised as important for achieving rates of 100% achievable, however, the return of conservation and species recovery objectives translocated chicks to release sites is still awaiting (Aikman et al. -

Recording the Manx Shearwater

RECORDING THE MANX There Kennedy and Doctor Blair, SHEARWATER Tall Alan and John stout There Min and Joan and Sammy eke Being an account of Dr. Ludwig Koch's And Knocks stood all about. adventures in the Isles of Scilly in the year of our Lord nineteen “ Rest, Ludwig, rest," the doctor said, hundred and fifty one, in the month of But Ludwig he said "NO! " June. This weather fine I dare not waste, To Annet I will go. This very night I'll records make, (If so the birds are there), Of Shearwaters* beneath the sod And also in the air." So straight to Annet's shores they sped And straight their task began As with a will they set ashore Each package and each man Then man—and woman—bent their backs And struggled up the rock To where his apparatus was Set up by Ludwig Koch. And some the heavy gear lugged up And some the line deployed, Until the arduous task was done And microphone employed. Then Ludwig to St. Agnes hied His hostess fair to greet; And others to St. Mary's went To get a bite to eat. Bold Ludwig Koch from London came, That night to Annet back they came, He travelled day and night And none dared utter word Till with his gear on Mary's Quay While Ludwig sought to test his set At last he did alight. Whereon he would record. There met him many an ardent swain Alas! A heavy dew had drenched To lend a helping hand; The cable laid with care, And after lunch they gathered round, But with a will the helpers stout A keen if motley band. -

Cordell Bank Ocean Monitoring Program (CBOMP)

Cordell Bank Ocean Monitoring Program (CBOMP) Peter Pyle1, Michael Carver1, Carol Keiper3, Ben Becker2, Dan Howard1 1Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary, 2Point Reyes National Seashore, 3Oikonos INTRODUCTION METHODS – OCEANOGRAPHY Cordell Bank National Marine Sanctuary (CBNMS) initiated a long-term Monitoring Program in - Thermosalinograph used to record sea surface temperature (SST) and sea surface salinity January 2004. Monitoring objectives include: continuously along transect lines. - CTD casts performed at selected locations using a SEABIRD SBE 19; data processed using - Describe the planktonic and vertebrate fauna relative to oceanography SBE software and displayed using Surfer 7.0 . - Assess temporal and spatial variation in occurrence and abundance of fauna and oceanography - Simrad EK60 echosounder with single 120Khz split-beam transducer used to estimate krill - Encourage collaborators to perform integrated ancillary research from the vessel abundance. - ArcView 9.0 Geographical Information System (GIS) used to integrate backscatter, fauna, and oceanography. SSTs were interpolated from TSG data using kriging. Temperature Sigma T Salinity Depth Figure 1. Above Survey zones for whales, birds and small mammals. Figure 2. Left Research Vessel C. magister at dock Spud Point Marina Bodega Bay Figure 3. Right Observ- ers on Transect during a Figures 5-7. CTD casts for October 13, 2004. Each colored bar represents an individual CTD cast of the 7 CTD cast locations shown in Figure CBOMP cruise in CBNMS 4. Depth of each cast is shown on the Y axis. Figure 4. Location of transects and CTD casts (dark circles) within CBNMS. PRELIMINARY RESULTS - 2004 METHODS – FAUNA - Eight surveys were conducted (due to weather and mechanical problems no surveys were - Surveys are conducted once/month using standard strip transect methodology (weather and ocean conducted in Feb, May, June, July). -

Plant Section Introduction

Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 RE-INTRODUCTION PRACTITIONERS DIRECTORY 1998 Compiled and Edited by Pritpal S. Soorae and Philip J. Seddon Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 © National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development, 1998 Printing and Publication details Legal Deposit no. 2218/9 ISBN: 9960-614-08-5 Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 Copies of this directory are available from: The Secretary General National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development Post Box 61681, Riyadh 11575 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Phone: +966-1-441-8700 Fax: +966-1-441-0797 Bibliographic Citation: Soorae, P. S. and Seddon, P. J. (Eds). 1998. Re-introduction Practitioners Directory. Published jointly by the IUCN Species Survival Commission’s Re-introduction Specialist Group, Nairobi, Kenya, and the National Commission for Wildlife Conservation and Development, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. 97pp. Cover Photo: Arabian Oryx Oryx leucoryx (NWRC Photo Library) Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 CONTENTS FOREWORD Professor Abdulaziz Abuzinadai PREFACE INTRODUCTION Dr Mark Stanley Price USING THE DIRECTORY ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PART A. ANIMALS I MOLLUSCS 1. GASTROPODS 1.1 Cittarium pica Top Shell 1.2 Placostylus ambagiosus Flax Snail 1.3 Placostylus ambagiosus Land Snail 1.4 Partula suturalis 1.5 Partula taeniata 1.6 Partula tahieana 1.7 Partula tohiveana 2. BIVALVES 2.1 Freshwater Mussels 2.2 Tridacna gigas Giant Clam II ARTHROPODS 3. ORTHOPTERA 3.1 Deinacrida sp. Weta 3.2 Deinacrida rugosa/parva Cook’s Strait Giant Weta Re-introduction Practitioners Directory - 1998 3.3 Gryllus campestris Field Cricket 4. LEPIDOPTERA 4.1 Carterocephalus palaemon Chequered Skipper 4.2 Lycaena dispar batavus Large Copper 4.3 Lycaena helle 4.4 Lycaeides melissa 4.5 Papilio aristodemus ponoceanus Schaus Swallowtail 5. -

Endemic Shearwaters Are Increasing in the Mediterranean in Relation to Factors That Are Closely Related to Human Activities

Global Ecology and Conservation 20 (2019) e00740 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Endemic shearwaters are increasing in the Mediterranean in relation to factors that are closely related to human activities * Beatriz Martín a, , Alejandro Onrubia a, Miguel Ferrer b a Fundacion Migres, CIMA, ctra. N-340, Km.85, Tarifa, E-11380, Cadiz, Spain b Applied Ecology Group, Donana~ Biological Station, CSIC, Seville, Spain article info abstract Article history: The aim of this study was to estimate global population trends of abundance of two Received 20 March 2019 endemic migratory seabird species breeding in the Mediterranean Sea, Balearic and Received in revised form 22 July 2019 Scopoli's shearwaters, from migration counts at the Strait of Gibraltar. Specifically, we Accepted 31 July 2019 assessed how regional environmental conditions (i.e. sea surface temperature, chlorophyll a concentration, NAO index and fish catches), as proxies of climate change, prey availability Keywords: and human-induced mortality factors, modulate the interannual variation in shearwater Chlorophyll numbers. The change in the migratory population size of both shearwater species was Climate change fi Fisheries estimated by tting Generalized Additive Models (GAM) to the annual counts against the fi Seabird year of observation. Speci cally, we modelled daily counts of migrant shearwaters during Monitoring the post-breeding season. Contrary to current estimates at breeding colonies, coastal-land based counts of migrating birds provide evidence that Baleric and Scopoli's shearwaters have been recently increasing in the Mediterranean Sea. Our results highlight that de- mographic patterns in these species are complex and non-linear, suggesting that most of the increases have happened recently and intimately bounded to environmental factors, such as chlorophyll concentration and fisheries, that are closely related to human activ- ities. -

ECOS 37-2-60 Reintroductions and Releases on the Isle Of

ECOS 37(2) 2016 ECOS 37(2) 2016 Reintroductions and releases on the Isle of Man Lessons from recent retreats Recent proposals for the release of white-tailed sea eagles and red squirrels on the Isle of Man received very different treatment, perhaps reflecting public perception of the animals and the public profile of the proponents, but also the political landscape of the island. NICK PINDER The Manx legal context The Isle of Man is a Crown dependency outside the EU but inside a common customs union with the United Kingdom. The Island can request that Westminster’s laws are extended to it but usually the Island passes its own laws which it promulgates at the annual Tynwald ceremony. Since it has a special relationship with the European Union, under Protocol 3, EU legislation covering agricultural and other trade is Point of Ayre: The Ayres is a large area of coastal heath and dune grassland in the north of the Isle of Mann usually translated into Manx law, as is UK law affecting customs controls. The 1980 island and location of the only National Nature Reserve. Endangered Species Act was therefore swiftly adopted in the Isle of Man but the Photo: Nick Pinder Wildlife and Countryside Act of the same year was not. A test for the legislation came in the early 1990s when some fox carcases turned When I arrived on the Isle of Man in 1987, the only wildlife legislation was a up. One was allegedly run over and then someone came forward having shot two dated Protection of Birds Act (1932-1975) but the newly formed Department of adults at a den site and dug up several cubs. -

The Feather Lice of the Levantine Shearwater Puffinus Yelkouan And

68 Zonfrillo & Palma Atlantic Seabirds 2(2) The feather lice of the Levantine Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan and its taxonomic status Veerluizen van de Yelkouanpijlstormvogel Puffinus yelkouan en de taxonomische status daarvan 2 Bernard Zonfrillo1 &Ricardo+L. Palma ‘Applied Ornithology Unit. Zoology Department. Glasgow University, Glasgow G12 8QQ. Scotland. U.K.; 'Museum ofNew Zealand, P.O. Box 467, Wellington, New Zealand. lice Four species of feather (Insecta: Phthiraptera) were found on one fresh dead and five museum skins of Levantine Shearwaters Puffinus yelkouan from various localities in the Mediterranean. Two of them, Halipeurus diversus (Kellogg, 1896) and Saemundssonia (Puffinoecus) kosswigi Timmermaan, 1962 (uniqueto P. yelkouan), had been recorded previously from this host; the other two, Austromenopon paululum (Kellogg & Chapman, 1899) and A. echinatum Edwards, 1960, represent new host-louse records. One bird collected fresh in Cyprus yielded the most lice, including 20 specimens of A. echinatum. The taxonomic position of the Levantine Shearwater is discussed it briefly and the opinion that be regardedas a distinct species is supported. Zonfnllo B. & Palma R.L. 2000 The feather lice of the Levantine Shearwater Puffinus yelkouan and its taxonomic status. Atlantic Seabirds 2(2): 68-72. INTRODUCTION Two species of feather lice (Insecta; Phthiraptera) have been recorded from Puffinus shearwaters in the Mediterranean.The Levantine Shearwater Puffinus is host diversus yelkouan to Halipeurus (Kellogg, 1896) and a unique louse, Saemundssonia (Puffinoecus) kosswigi Timmermann, 1962 (on the status of Puffinoecus, see Palma 1994). Palma et ai (1997) recorded only a single species of feather louse H. diversus) on 19 systematically deloused specimens of Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus Lowe, 1821 from the Balearic archipelago. -

Conservation Services Programme Project MIT2015-02: Mitigating

Conservation Services Programme Project MIT2015-02: Mitigating seabird captures during hauling on smaller longline vessels J. P. Pierre 6 April 2018 Executive summary ___________________________________________________________________________ Seabird captures in longline fisheries may occur on the set, soak or haul. Bycatch reduction measures are best developed, tested and implemented for reducing seabird captures occurring during longline sets. Measures affecting the nature and extent of haul captures, and mitigation approaches to reduce those captures, are not well-known. Further, the difficulty of accurately identifying captures as occurring on the haul means that live seabird captures are typically used as a proxy for haul captures in bycatch datasets. A global review shows four broad categories of mitigation used during longline hauling: physical barriers, measures that reduce the attractiveness of the haul area, deterrents, and operational approaches that are part of fishing. Of devices that operate as physical barriers to seabirds, bird exclusion devices, tori lines and towed buoys have been tested and proven effective in reducing seabird interactions with hauled longline gear. Discharging fish waste such that seabirds are not attracted to the hauling bay is another effective measure, and seabird abundance around vessels is reduced by retaining fish waste during hauling. While a number of deterrents and ad hoc or reactive approaches to reducing haul captures have been discussed in the literature (e.g. water sprays), these have generally not been empirically tested. Information collected by government fisheries observers on 73 bottom longline and 60 surface longline trips that have occurred since 1 October 2012 on New Zealand vessels < 34 m in overall length showed that most of these measures are in place here. -

Varnham, K. J. & Meier G. G. 2007. Rdum Tal-Madonna Rat Control

Rdum tal-Madonna rat control project December 2006 - March 2007 Final Report to BirdLife Malta & RSPB Karen Varnham Independent Invasive Species Consultant & Guntram G. Meier InGrip-Consulting & Animal Control, Senior Consultant March 2007 Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Methods 4 3. Results 8 4. Future of the rat control project 12 5. Recommendations 12 6. References 13 7. Acknowledgements 13 Appendices 1. Text of warning signs displayed at the site 14 2. Distribution of rat activity 15 3. Warden’s manual 19 Suggested citation: Varnham, K. J. & Meier G. G. (2007) Rdum tal-Madonna rat control project, December 2006 – March 2007, Final report. Unpublished report to BirdLife Malta & RSPB, 28pp. Contact details: [email protected] Front cover illustration: rock pool on the South Cliffs of the Rdum tal-Madonna SPA 2 1. Introduction Rat control at the Rdum tal-Madonna Special Protected Area (SPA) was carried out as part of BirdLife Malta’s ongoing project to protect the Yelkouan shearwater, Puffinus yelkouan (EU Life Project LIFE06/ NAT/ MT/ 000097, SPA Site and Sea Actions saving Puffinus yelkouan in Malta). These cliff-nesting birds are known to be at great risk from rat predation, with annual losses of eggs and chicks between 40 and 100%. Around one-third of Malta’s 1500 breeding pairs of P. yelkouan nest at this site, making it an obvious focal point for conservation efforts (references in EU Project Proposal). The relatively small size of the SPA (75.3ha), and that it is surrounded by the ocean on three sides, make it a good site for rat control. -

Post-Release Survival of Fallout Newell's Shearwater Fledglings From

Vol. 43: 39–50, 2020 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published September 3 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01051 Endang Species Res OPEN ACCESS Post-release survival of fallout Newell’s shearwater fledglings from a rescue and rehabilitation program on Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i André F. Raine1,*, Tracy Anderson2, Megan Vynne1, Scott Driskill1, Helen Raine3, Josh Adams4 1Kaua‘i Endangered Seabird Recovery Project (KESRP), Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit (PCSU), University of Hawai‘i and Division of Forestry and Wildlife, State of Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Hanapepe, HI 96716, USA 2Save Our Shearwaters, Humane Society, 3-825 Kaumualii Hwy, Lihue, HI 96766, USA 3Archipelago Research and Conservation, 3861 Ulu Alii Street, Kalaheo, HI 96741, USA 4U.S. Geological Survey, Western Ecological Research Center, Santa Cruz Field Station 2885 Mission St., Santa Cruz, CA 95060, USA ABSTRACT: Light attraction impacts nocturnally active fledgling seabirds worldwide and is a par- ticularly acute problem on Kaua‘i (the northern-most island in the main Hawaiian Island archipel- ago) for the Critically Endangered Newell’s shearwater Puffinus newelli. The Save Our Shearwaters (SOS) program was created in 1979 to address this issue and to date has recovered and released to sea more than 30 500 fledglings. Although the value of the program for animal welfare is clear, as birds cannot simply be left to die, no evaluation exists to inform post-release survival. We used satellite transmitters to track 38 fledglings released by SOS and compared their survival rates (assessed by tag transmission duration) to those of 12 chicks that fledged naturally from the moun- tains of Kaua‘i. -

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

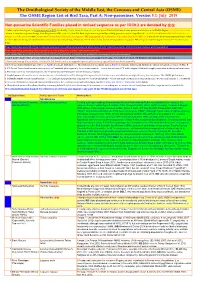

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately.