Seabirds in the Gulf of Lions Shelf and Slope Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Population Estimates of a Critically Endangered Species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus Mauretanicus , Based on Coastal Migration Counts

Bird Conservation International (2016) 26 :87 –99 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S095927091400032X New population estimates of a critically endangered species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus , based on coastal migration counts GONZALO M. ARROYO , MARÍA MATEOS-RODRÍGUEZ , ANTONIO R. MUÑOZ , ANDRÉS DE LA CRUZ , DAVID CUENCA and ALEJANDRO ONRUBIA Summary The Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is considered one of the most threatened seabirds in the world, with the breeding population thought to be in the range of 2,000–3,200 breeding pairs, from which global population has been inferred as 10,000 to 15,000 birds. To test whether the actual population of Balearic Shearwaters is larger than presently thought, we analysed the data from four land-based census campaigns of Balearic Shearwater post-breeding migration through the Strait of Gibraltar (mid-May to mid-July 2007–2010). The raw results of the counts, covering from 37% to 67% of the daylight time throughout the migratory period, all revealed figures in excess of 12,000 birds, and went up to almost 18,000 in two years. Generalised Additive Models were used to estimate the numbers of birds passing during the time periods in which counts were not undertaken (count gaps), and their associated error. The addition of both counted and esti- mated birds reveals figures of between 23,780 and 26,535 Balearic Shearwaters migrating along the north coast of the Strait of Gibraltar in each of the four years of our study. The effects of several sources of bias suggest a slight potential underestimation in our results. -

Evolution and Presence of Diurnal Predatory Birds in the Carpathian Basin

Ornis Hungarica 2018. 26(1): 102–123. DOI: 10.1515/orhu-2018-0008 Evolution and presence of diurnal predatory birds in the Carpathian Basin Jenő (Eugen) KESSLER Received: February 05, 2018 – Revised: May 03, 2018 – Accepted: May 08, 2018 Kessler, J. (E.) 2018. Evolution and presence of diurnal predatory birds (Ord. Accipitriformes, and Falconiformes) in the Carpathian Basin. – Ornis Hungarica 26(1): 102–123. DOI: 10.1515/ orhu-2018-0008 Abstract The author describes the presence of the oldest extinct diurnal birds of prey species in the world and fossilized representatives of different families, as well as the presence of recent species in the Car- pathian Basin among fossilized remains. In case of ospreys, one of the oldest known materials is classified as a new extinct species named Pandion pannonicus. The text is supplemented by a plate and a size chart. Keywords: birds of prey, evolution, Carpathian Basin, Osprey, eagles, buzzards, vultures, falcons, Pandion pan- nonicus sp.n. Összefoglalás A szerző bemutatja a nappali ragadozók kihalt fajait és a különböző családok fosszilis képviselő- it, valamint a recens fajok Kárpát-medencei jelenlétét a fosszilis maradványokban. A halászsasok között itt kerül először leírásra egy új faj is (Pandion pannonicus), amely egyben az egyik legrégebbi is az eddig ismert anyagok- ból. A szöveget egy ábra és egy mérettáblázat egészíti ki. Kulcsszavak: ragadozó madarak, evolúció, Kárpát-medence, halászsas, sas, ölyv, keselyű, sólyom, Pandion pan- nonicus sp.n. Department of Paleontology, Eötvös Loránd University, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter sétány 1/c, Hungary, e-mail: [email protected] Introduction Accipitridae is the most populous family in terms of species (eagles, goshawks, kites, harri- ers and vultures belong in the group). -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor How They Arise, Modify and Vanish

Fascinating Life Sciences Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Fascinating Life Sciences This interdisciplinary series brings together the most essential and captivating topics in the life sciences. They range from the plant sciences to zoology, from the microbiome to macrobiome, and from basic biology to biotechnology. The series not only highlights fascinating research; it also discusses major challenges associated with the life sciences and related disciplines and outlines future research directions. Individual volumes provide in-depth information, are richly illustrated with photographs, illustrations, and maps, and feature suggestions for further reading or glossaries where appropriate. Interested researchers in all areas of the life sciences, as well as biology enthusiasts, will find the series’ interdisciplinary focus and highly readable volumes especially appealing. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15408 Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Editor Dieter Thomas Tietze Natural History Museum Basel Basel, Switzerland ISSN 2509-6745 ISSN 2509-6753 (electronic) Fascinating Life Sciences ISBN 978-3-319-91688-0 ISBN 978-3-319-91689-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91689-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948152 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Endemic Shearwaters Are Increasing in the Mediterranean in Relation to Factors That Are Closely Related to Human Activities

Global Ecology and Conservation 20 (2019) e00740 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Endemic shearwaters are increasing in the Mediterranean in relation to factors that are closely related to human activities * Beatriz Martín a, , Alejandro Onrubia a, Miguel Ferrer b a Fundacion Migres, CIMA, ctra. N-340, Km.85, Tarifa, E-11380, Cadiz, Spain b Applied Ecology Group, Donana~ Biological Station, CSIC, Seville, Spain article info abstract Article history: The aim of this study was to estimate global population trends of abundance of two Received 20 March 2019 endemic migratory seabird species breeding in the Mediterranean Sea, Balearic and Received in revised form 22 July 2019 Scopoli's shearwaters, from migration counts at the Strait of Gibraltar. Specifically, we Accepted 31 July 2019 assessed how regional environmental conditions (i.e. sea surface temperature, chlorophyll a concentration, NAO index and fish catches), as proxies of climate change, prey availability Keywords: and human-induced mortality factors, modulate the interannual variation in shearwater Chlorophyll numbers. The change in the migratory population size of both shearwater species was Climate change fi Fisheries estimated by tting Generalized Additive Models (GAM) to the annual counts against the fi Seabird year of observation. Speci cally, we modelled daily counts of migrant shearwaters during Monitoring the post-breeding season. Contrary to current estimates at breeding colonies, coastal-land based counts of migrating birds provide evidence that Baleric and Scopoli's shearwaters have been recently increasing in the Mediterranean Sea. Our results highlight that de- mographic patterns in these species are complex and non-linear, suggesting that most of the increases have happened recently and intimately bounded to environmental factors, such as chlorophyll concentration and fisheries, that are closely related to human activ- ities. -

CISO-COI Check-List of Italian Birds - 2020

https://doi.org/10.30456/AVO.2021_checklist_en Avocetta 45: 21 - 82 (2021) CISO-COI Check-list of Italian birds - 2020 Nicola Baccetti1*, Giancarlo Fracasso2* & Commissione Ornitologica Italiana (COI) 1ISPRA - Istituto Superiore per la Ricerca e la Protezione Ambientale - Via Ca’ Fornacetta 9, 40064 Ozzano dell’Emilia (BO), Italy 2Gruppo Nisoria - c/o Museo naturalistico-archeologico, Contrà S. Corona 4, 36100 Vicenza, Italy *corresponding authors: [email protected], [email protected] NB 0000-0001-6579-6060, GF 0000-0002-6837-5752 Abstract - This paper upgrades and updates the checklist of the bird species recorded in Italy between 1800 and 2019. For the first time, it also includes subspecies. The classification, taxonomy and English names are based on «The Handbook of the Birds of the World & BirdLife International Checklist». The Italian list contains at present 551 species and 702 taxonomic units, including in the latter both the subspecies and the monotypic species. Each of them has been allocated to the AERC categories A, B or C according to four different frequency codes. Since the publication of the previous list (2009), 25 species have been added. The currently breeding avifauna includes 287 species: additional 10 species are regarded as nationally extinct breeders. The Italian checklist, that will be regularly updated, is available on the website of the CISO-COI (https://ciso-coi.it/coi/ checklist-ciso-coi-degli-uccelli-italiani/). INTRODUCTION coded A, B or C, we avoided adding an E status to all Ten years after the publication of the first CISO-COI cases of non-natural occurrence of A or C species. -

European Red List of Birds

European Red List of Birds Compiled by BirdLife International Published by the European Commission. opinion whatsoever on the part of the European Commission or BirdLife International concerning the legal status of any country, Citation: Publications of the European Communities. Design and layout by: Imre Sebestyén jr. / UNITgraphics.com Printed by: Pannónia Nyomda Picture credits on cover page: Fratercula arctica to continue into the future. © Ondrej Pelánek All photographs used in this publication remain the property of the original copyright holder (see individual captions for details). Photographs should not be reproduced or used in other contexts without written permission from the copyright holder. Available from: to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) Certain mobile telephone operators do not allow access to 00 800 numbers or these calls may be billed Published by the European Commission. A great deal of additional information on the European Union is available on the Internet. It can be accessed through the Europa server (http://europa.eu). Cataloguing data can be found at the end of this publication. ISBN: 978-92-79-47450-7 DOI: 10.2779/975810 © European Union, 2015 Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Printed in Hungary. European Red List of Birds Consortium iii Table of contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................................1 Executive summary ...................................................................................................................................................5 1. -

Partial Migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates Pelagicus Melitensis

Lago et al.: Partial migration in Mediterranean Storm Petrel 105 PARTIAL MIGRATION IN THE MEDITERRANEAN STORM PETREL HYDROBATES PELAGICUS MELITENSIS PAULO LAGO*, MARTIN AUSTAD & BENJAMIN METZGER BirdLife Malta, 57/28 Triq Abate Rigord, Ta’ Xbiex XBX 1120, Malta *([email protected]) Received 27 November 2018, accepted 05 February 2019 ABSTRACT LAGO, P., AUSTAD, M. & METZGER, B. 2019. Partial migration in the Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. Marine Ornithology 47: 105–113. Studying the migration routes and wintering areas of seabirds is crucial to understanding their ecology and to inform conservation efforts. Here we present results of a tracking study carried out on the little-known Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. During the 2016 breeding season, Global Location Sensor (GLS) tags were deployed on birds at the largest Mediterranean colony: the islet of Filfla in the Maltese Archipelago. The devices were retrieved the following season, revealing hitherto unknown movements and wintering areas of this species. Most individuals remained in the Mediterranean throughout the year, with birds shifting westwards or remaining in the central Mediterranean during winter. However, one bird left the Mediterranean through the Strait of Gibraltar and wintered in the North Atlantic. Our results from GLS tracking, which are supported by data from ringed and recovered birds, point toward a system of partial migration with high inter-individual variation. This highlights the importance of trans-boundary marine protection for the conservation of vulnerable seabirds. Key words: Procellariformes, movement, geolocation, wintering, Malta, capture-mark-recovery INTRODUCTION The Mediterranean Storm Petrel has been described as sedentary, because birds are present in their breeding areas throughout the year The Mediterranean Storm Petrel Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis is (Zotier et al. -

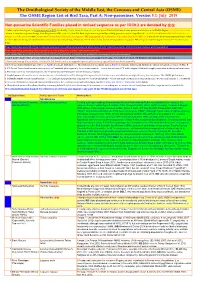

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

Tracking, Feather Moult and Stable Isotopes Reveal Foraging Behaviour

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2017) 23, 130–145 BIODIVERSITY Tracking, feather moult and stable RESEARCH isotopes reveal foraging behaviour of a critically endangered seabird during the non-breeding season Rhiannon E. Meier1*, Stephen C. Votier2, Russell B. Wynn1, Tim Guilford3, Miguel McMinn Grive4, Ana Rodrıguez5, Jason Newton6, Louise Maurice7, Tiphaine Chouvelon8,9, Aurelie Dessier8 and Clive N. Trueman10 1National Oceanography Centre, European ABSTRACT Way, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK, Aim The movement patterns of marine top predators are likely to reflect 2Environment and Sustainability Institute, responses to prey distributions, which themselves can be influenced by factors University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9FE, UK, 3Animal such as climate and fisheries. The critically endangered Balearic shearwater Behaviour Research Group, Department of Puffinus mauretanicus has shown a recent northwards shift in non-breeding dis- Zoology, University of Oxford, The tribution, tentatively linked to changing forage fish distribution and/or fisheries A Journal of Conservation Biogeography Tinbergen Building, South Parks Road, activity. Here, we provide the first information on the foraging ecology of this Oxford OX1 3PS, UK, 4Biogeografia, species during the non-breeding period. geodinamica i sedimentaciodela Location Breeding grounds in Mallorca, Spain, and non-breeding areas in the Mediterrania occidental (BIOGEOMED), north-east Atlantic and western Mediterranean. Universitat de les Illes Balears, Cra. de Valldemossa, km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Illes Methods Birdborne geolocation was used to identify non-breeding grounds. Balears, Spain, 5Balearic Shearwater Information on feather moult (from digital images) and stable isotopes (of Conservation Association, Puig del Teide 4 - both primary wing feathers and potential prey items) was combined to infer 315, Palmanova 07181, Illes Balears, Spain, foraging behaviour during the non-breeding season. -

What Genetics Tell Us About the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Balearic Shearwater?

BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION 137 (2007) 283– 293 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon What genetics tell us about the conservation of the critically endangered Balearic Shearwater? Meritxell Genovarta,b,*, Daniel Oroa, Javier Justec, Giorgio Bertorelleb aInstitut Mediterrani d’Estudis Avanc¸ats IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), Miquel Marque`s 21, 07190 Esporles, Mallorca, Spain bDipartimento di Biologia, Universita` di Ferrara, Via Borsari 46, 44100 Ferrara, Italy cEstacio´n Biolo´gica de Don˜ ana (CSIC), Avda. Ma Luisa s/n, Aptdo. 41080 Sevilla, Spain ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is one of the most critically endangered sea- Received 20 March 2006 birds in the world. The species is endemic to the Balearic archipelago, and conservation Received in revised form concerns are the low number of breeding pairs, the low adult survival, and the possible 5 February 2007 hybridization with a sibling species, the morphologically smaller Yelkouan shearwater (P. Accepted 18 February 2007 yelkouan). We sampled almost the entire breeding range of the species and analyzed the genetic variation at two mitochondrial DNA regions. No genetic evidence of population decline was found. Despite the observed philopatry, we detected a weak population struc- Keywords: ture mainly due to connectivity among colonies higher than expected, but also to a Pleis- Conservation genetics tocene demographic expansion. Some colonies showed a high imbalance between Introgression immigration and emigration rates, suggesting spatial heterogeneity in patch quality. Population expansion Genetic evidence of maternal introgression from the sibling species was reinforced, but Population structure almost only in a peripheral colony and not followed, at least to date, by the spread of the Puffinus mauretanicus introgressed mtDNA lineages. -

Balearic Islands Area

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Title/Name of the area: Balearic Islands Area Presented by: Greenpeace International as a submission to the Mediterranean Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs), 7 to 11 April 2014, Málaga, Spain. Contact person: Sofia Tsenikli, Senior Political Advisor, Email: [email protected]; tel: +30 6979443306 Information in this submission has been presented at the CBD Expert Workshop on Scientific and Technical Guidance on the use of Biogeographic Classification Systems and Identification of Marine Areas beyond national jurisdiction in need of protection, 29 September - 2 October 2009, in Ottawa, Canada, and is included in the official report of the workshop which can be accessed here. Abstract The Balearic Archipelago is one of the richest European regions in terms of marine animal species diversity and is characterized by a wide range of ecosystem types (e.g. maërl beds, Leptometra beds, soft red algae communities, Posidonia meadows, etc) (Aguilar et al.,2007b) . Some of these communities are considered rare on a European scale. The area’s complex oceanography results in high levels of productivity, reflected by its importance as a feeding ground for a wide range of species, including fin and sperm whales, loggerhead turtles and as a crucial spawning ground for threatened Bluefin tuna. The area is also an important breeding ground for the endemic Balearic shearwater. Introduction In 2006 Greenpeace published a proposal for a regional network of large-scale marine reserves with the aim of protecting the full spectrum of life in the Mediterranean (see Figure 1) (Greenpeace 2006).