Balearic Shearwater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Population Estimates of a Critically Endangered Species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus Mauretanicus , Based on Coastal Migration Counts

Bird Conservation International (2016) 26 :87 –99 . © BirdLife International, 2014 doi:10.1017/S095927091400032X New population estimates of a critically endangered species, the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus , based on coastal migration counts GONZALO M. ARROYO , MARÍA MATEOS-RODRÍGUEZ , ANTONIO R. MUÑOZ , ANDRÉS DE LA CRUZ , DAVID CUENCA and ALEJANDRO ONRUBIA Summary The Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is considered one of the most threatened seabirds in the world, with the breeding population thought to be in the range of 2,000–3,200 breeding pairs, from which global population has been inferred as 10,000 to 15,000 birds. To test whether the actual population of Balearic Shearwaters is larger than presently thought, we analysed the data from four land-based census campaigns of Balearic Shearwater post-breeding migration through the Strait of Gibraltar (mid-May to mid-July 2007–2010). The raw results of the counts, covering from 37% to 67% of the daylight time throughout the migratory period, all revealed figures in excess of 12,000 birds, and went up to almost 18,000 in two years. Generalised Additive Models were used to estimate the numbers of birds passing during the time periods in which counts were not undertaken (count gaps), and their associated error. The addition of both counted and esti- mated birds reveals figures of between 23,780 and 26,535 Balearic Shearwaters migrating along the north coast of the Strait of Gibraltar in each of the four years of our study. The effects of several sources of bias suggest a slight potential underestimation in our results. -

Bird Watching in Cyprus a Brief Guide for Visitors To

BIRD WATCHING IN CYPRUS A BRIEF GUIDE FOR VISITORS TO THE ISLAND 1 Information on Cyprus in general The position of Cyprus in the eastern Mediterranean with Turkey to the north, Syria to the east and Egypt to the south, places it on one of the major migration routes in the Mediterranean and makes it a stop off point for many species which pass each year from Europe/Asia to Africa via the Nile Delta. The birds that occur regularly on passage form a large percentage of the ‘Cyprus list’ that currently totals nearly 380 species. Of these only around 50 are resident and around 40 are migrant species that regularly or occasionally breed. The number of birds passing over during the spring and autumn migration periods are impressive, as literally millions of birds pour through Cyprus. Spring migration gets underway in earnest around the middle of March, usually depending on how settled the weather is, and continues into May. A few early arrivals can even be noted in February, especially the swallows, martins and swifts, some wheatears and the Great Spotted Cuckoo Clamator glandarius. Slender-billed Gulls Larus genei and herons can be seen in flocks along the coastline. Each week seems to provide a different species to watch for. The end of March sees Roller Coracias garrulous, Masked Shrike Lanius nubicus, Cretzschmar’s Bunting Emberiza caesia, Black-headed Wagtails Motacilla flava feldegg and Red-rumped Swallows Cecropsis daurica, while on the wetlands Marsh Sandpipers Tringa stagnatilis, Collared Pratincole Glareola pratincola, Spur-winged Vanellus spinosus and Greater Sand Plover Charadrius leschenaultii can be seen. -

Endemic Shearwaters Are Increasing in the Mediterranean in Relation to Factors That Are Closely Related to Human Activities

Global Ecology and Conservation 20 (2019) e00740 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Global Ecology and Conservation journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/gecco Original Research Article Endemic shearwaters are increasing in the Mediterranean in relation to factors that are closely related to human activities * Beatriz Martín a, , Alejandro Onrubia a, Miguel Ferrer b a Fundacion Migres, CIMA, ctra. N-340, Km.85, Tarifa, E-11380, Cadiz, Spain b Applied Ecology Group, Donana~ Biological Station, CSIC, Seville, Spain article info abstract Article history: The aim of this study was to estimate global population trends of abundance of two Received 20 March 2019 endemic migratory seabird species breeding in the Mediterranean Sea, Balearic and Received in revised form 22 July 2019 Scopoli's shearwaters, from migration counts at the Strait of Gibraltar. Specifically, we Accepted 31 July 2019 assessed how regional environmental conditions (i.e. sea surface temperature, chlorophyll a concentration, NAO index and fish catches), as proxies of climate change, prey availability Keywords: and human-induced mortality factors, modulate the interannual variation in shearwater Chlorophyll numbers. The change in the migratory population size of both shearwater species was Climate change fi Fisheries estimated by tting Generalized Additive Models (GAM) to the annual counts against the fi Seabird year of observation. Speci cally, we modelled daily counts of migrant shearwaters during Monitoring the post-breeding season. Contrary to current estimates at breeding colonies, coastal-land based counts of migrating birds provide evidence that Baleric and Scopoli's shearwaters have been recently increasing in the Mediterranean Sea. Our results highlight that de- mographic patterns in these species are complex and non-linear, suggesting that most of the increases have happened recently and intimately bounded to environmental factors, such as chlorophyll concentration and fisheries, that are closely related to human activ- ities. -

Is the Sardinian Warbler Sylvia Melanocephala Displacing the Endemic Cyprus Warbler S

Is the Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala displacing the endemic Cyprus Warbler S. melanothorax on Cyprus? PETER FLINT & ALISON MCARTHUR We firstly describe the history, status, distribution and habitats of the two species on the island. In the light of this the evidence for a decline in Cyprus Warbler numbers in the areas colonised by Sardinian Warbler is assessed and is found to be compelling. Possible reasons for this decline are examined; they are apparently complex, but primarily Cyprus Warbler appears to have stronger interspecific territoriality than Sardinian Warbler and may treat the latter territorially at least to some extent as a conspecific, with some tendency to avoid its home-ranges, especially their centres. Other important factors may be interspecific aggression from Sardinian Warbler (where its population density is high) which might reduce Cyprus Warbler’s ability to establish breeding territories; and competition from Sardinian Warbler for food and for autumn/winter territories. Also, Sardinian Warbler appears to be more efficient in exploiting the habitats of the endemic species, which may have reached a stage in its evolution as an island endemic where it is vulnerable to such an apparently fitter invading congener from the mainland. The changing climate on the island may also be a factor. We conclude that Sardinian Warbler does appear to be displacing Cyprus Warbler, and we recommend that the latter’s conservation status be re-assessed. INTRODUCTION Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala, previously known only as a winter visitor, was found breeding on Cyprus in 1992 (Frost 1995) and is rapidly spreading through the island (eg Cozens & Stagg 1998, Cyprus Ornithological Society (1957)/BirdLife Cyprus annual reports and newsletters, Ieronymidou et al 2012) often breeding at high densities within the same areas as the endemic Cyprus Warbler S. -

Tape Lures Swell Bycatch on a Mediterranean Island Harbouring Illegal Bird Trapping

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.13.991034; this version posted March 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Tape lures swell bycatch on a Mediterranean island 2 harbouring illegal bird trapping 3 Matteo Sebastianelli1, Georgios Savva1, Michaella Moysi1, and 4 Alexander N. G. Kirschel1* 5 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cyprus, PO Box 20537, Nicosia 1678, 6 Cyprus 7 8 Keywords: Cyprus, illegal bird hunting, Sylvia atricapilla, Sylvia melanocephala, playback 9 experiment, warbler. 10 *Email of corresponding author: [email protected] 11 12 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.13.991034; this version posted March 15, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 13 Abstract 14 Mediterranean islands are critical for migrating birds, providing shelter and sustenance 15 for millions of individuals each year. Humans have long exploited bird migration 16 through hunting and illegal trapping. On the island of Cyprus, trapping birds during 17 their migratory peak is considered a local tradition, but has long been against the law. 18 Illegal bird trapping is a lucrative business, however, with trappers using tape lures that 19 broadcast species’ vocalizations because it is expected to increase numbers of target 20 species. -

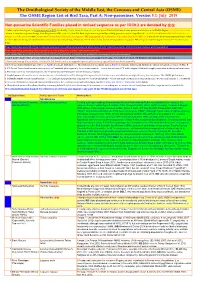

ORL 5.1 Non-Passerines Final Draft01a.Xlsx

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part A: Non-passerines. Version 5.1: July 2019 Non-passerine Scientific Families placed in revised sequence as per IOC9.2 are denoted by ֍֍ A fuller explanation is given in Explanation of the ORL, but briefly, Bright green shading of a row (eg Syrian Ostrich) indicates former presence of a taxon in the OSME Region. Light gold shading in column A indicates sequence change from the previous ORL issue. For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates added information since the previous ORL version or the Conservation Threat Status (Critically Endangered = CE, Endangered = E, Vulnerable = V and Data Deficient = DD only). Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative convenience and may change. Please do not cite them in any formal correspondence or papers. NB: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text indicate recent or data-driven major conservation concerns. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. English names shaded thus are taxa on BirdLife Tracking Database, http://seabirdtracking.org/mapper/index.php. Nos tracked are small. NB BirdLife still lump many seabird taxa. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. -

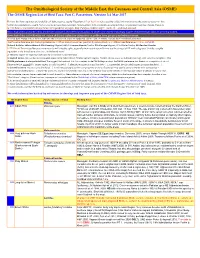

OSME List V3.4 Passerines-2

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa: Part C, Passerines. Version 3.4 Mar 2017 For taxa that have unproven and probably unlikely presence, see the Hypothetical List. Red font indicates either added information since the previous version or that further documentation is sought. Not all synonyms have been examined. Serial numbers (SN) are merely an administrative conveninence and may change. Please do not cite them as row numbers in any formal correspondence or papers. Key: Compass cardinals (eg N = north, SE = southeast) are used. Rows shaded thus and with yellow text denote summaries of problem taxon groups in which some closely-related taxa may be of indeterminate status or are being studied. Rows shaded thus and with white text contain additional explanatory information on problem taxon groups as and when necessary. A broad dark orange line, as below, indicates the last taxon in a new or suggested species split, or where sspp are best considered separately. The Passerine Reference List (including References for Hypothetical passerines [see Part E] and explanations of Abbreviated References) follows at Part D. Notes↓ & Status abbreviations→ BM=Breeding Migrant, SB/SV=Summer Breeder/Visitor, PM=Passage Migrant, WV=Winter Visitor, RB=Resident Breeder 1. PT=Parent Taxon (used because many records will antedate splits, especially from recent research) – we use the concept of PT with a degree of latitude, roughly equivalent to the formal term sensu lato , ‘in the broad sense’. 2. The term 'report' or ‘reported’ indicates the occurrence is unconfirmed. -

Tracking, Feather Moult and Stable Isotopes Reveal Foraging Behaviour

Diversity and Distributions, (Diversity Distrib.) (2017) 23, 130–145 BIODIVERSITY Tracking, feather moult and stable RESEARCH isotopes reveal foraging behaviour of a critically endangered seabird during the non-breeding season Rhiannon E. Meier1*, Stephen C. Votier2, Russell B. Wynn1, Tim Guilford3, Miguel McMinn Grive4, Ana Rodrıguez5, Jason Newton6, Louise Maurice7, Tiphaine Chouvelon8,9, Aurelie Dessier8 and Clive N. Trueman10 1National Oceanography Centre, European ABSTRACT Way, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK, Aim The movement patterns of marine top predators are likely to reflect 2Environment and Sustainability Institute, responses to prey distributions, which themselves can be influenced by factors University of Exeter, Penryn Campus, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9FE, UK, 3Animal such as climate and fisheries. The critically endangered Balearic shearwater Behaviour Research Group, Department of Puffinus mauretanicus has shown a recent northwards shift in non-breeding dis- Zoology, University of Oxford, The tribution, tentatively linked to changing forage fish distribution and/or fisheries A Journal of Conservation Biogeography Tinbergen Building, South Parks Road, activity. Here, we provide the first information on the foraging ecology of this Oxford OX1 3PS, UK, 4Biogeografia, species during the non-breeding period. geodinamica i sedimentaciodela Location Breeding grounds in Mallorca, Spain, and non-breeding areas in the Mediterrania occidental (BIOGEOMED), north-east Atlantic and western Mediterranean. Universitat de les Illes Balears, Cra. de Valldemossa, km 7.5, 07122 Palma, Illes Methods Birdborne geolocation was used to identify non-breeding grounds. Balears, Spain, 5Balearic Shearwater Information on feather moult (from digital images) and stable isotopes (of Conservation Association, Puig del Teide 4 - both primary wing feathers and potential prey items) was combined to infer 315, Palmanova 07181, Illes Balears, Spain, foraging behaviour during the non-breeding season. -

What Genetics Tell Us About the Conservation of the Critically Endangered Balearic Shearwater?

BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION 137 (2007) 283– 293 available at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon What genetics tell us about the conservation of the critically endangered Balearic Shearwater? Meritxell Genovarta,b,*, Daniel Oroa, Javier Justec, Giorgio Bertorelleb aInstitut Mediterrani d’Estudis Avanc¸ats IMEDEA (CSIC-UIB), Miquel Marque`s 21, 07190 Esporles, Mallorca, Spain bDipartimento di Biologia, Universita` di Ferrara, Via Borsari 46, 44100 Ferrara, Italy cEstacio´n Biolo´gica de Don˜ ana (CSIC), Avda. Ma Luisa s/n, Aptdo. 41080 Sevilla, Spain ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is one of the most critically endangered sea- Received 20 March 2006 birds in the world. The species is endemic to the Balearic archipelago, and conservation Received in revised form concerns are the low number of breeding pairs, the low adult survival, and the possible 5 February 2007 hybridization with a sibling species, the morphologically smaller Yelkouan shearwater (P. Accepted 18 February 2007 yelkouan). We sampled almost the entire breeding range of the species and analyzed the genetic variation at two mitochondrial DNA regions. No genetic evidence of population decline was found. Despite the observed philopatry, we detected a weak population struc- Keywords: ture mainly due to connectivity among colonies higher than expected, but also to a Pleis- Conservation genetics tocene demographic expansion. Some colonies showed a high imbalance between Introgression immigration and emigration rates, suggesting spatial heterogeneity in patch quality. Population expansion Genetic evidence of maternal introgression from the sibling species was reinforced, but Population structure almost only in a peripheral colony and not followed, at least to date, by the spread of the Puffinus mauretanicus introgressed mtDNA lineages. -

Balearic Islands Area

Template for Submission of Scientific Information to Describe Areas Meeting Scientific Criteria for Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas Title/Name of the area: Balearic Islands Area Presented by: Greenpeace International as a submission to the Mediterranean Regional Workshop to Facilitate the Description of Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Areas (EBSAs), 7 to 11 April 2014, Málaga, Spain. Contact person: Sofia Tsenikli, Senior Political Advisor, Email: [email protected]; tel: +30 6979443306 Information in this submission has been presented at the CBD Expert Workshop on Scientific and Technical Guidance on the use of Biogeographic Classification Systems and Identification of Marine Areas beyond national jurisdiction in need of protection, 29 September - 2 October 2009, in Ottawa, Canada, and is included in the official report of the workshop which can be accessed here. Abstract The Balearic Archipelago is one of the richest European regions in terms of marine animal species diversity and is characterized by a wide range of ecosystem types (e.g. maërl beds, Leptometra beds, soft red algae communities, Posidonia meadows, etc) (Aguilar et al.,2007b) . Some of these communities are considered rare on a European scale. The area’s complex oceanography results in high levels of productivity, reflected by its importance as a feeding ground for a wide range of species, including fin and sperm whales, loggerhead turtles and as a crucial spawning ground for threatened Bluefin tuna. The area is also an important breeding ground for the endemic Balearic shearwater. Introduction In 2006 Greenpeace published a proposal for a regional network of large-scale marine reserves with the aim of protecting the full spectrum of life in the Mediterranean (see Figure 1) (Greenpeace 2006). -

EBBA2 Sardinian Warbler Sylvia Melanocephala the Sardinian

Herrando, S., Rabaça, João E. & Boyla, Kerem A. 2020. Sylvia melanocephala Sardinian Warbler. In Keller, V., Herrando, S. Vorisek, P. et al. European Breeding Bird Atlas 2: distribution, abundance and change. Ed. European Bird Census Council & Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Pp: 678-679. EBBA2 Sardinian Warbler Sylvia melanocephala The Sardinian Warbler is mainly distributed around the Mediterranean Basin, from the Iberian Peninsula and the Maghreb to the Anatolian Peninsula and the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. The subspecies S. m. melanocephala occurs in the most of the EBBA2 area but S. m. leucogastra, is found in the Canary Islands. It is mainly a resident species but individuals breeding in the coldest areas of its range often carry out short distance movements, mostly within the overall breeding range but sometimes reaching parts of Sahara and Arabia. Birds breeding around the Black sea are completely migratory [HBW]. The coverage in EBBA2 for this species can be considered as very good. The 50-km map shows its wide distribution in all the Mediterranean peninsulas and islands (even in the small ones). Only in parts of Turkey there are some potential gaps of coverage (e.g. in the S Mediterranean coast) that do not hinder the interpretation of the overall patterns of distribution. The Sardinian Warbler is the most generalist Mediterranean warbler, occurring in a great variety of habitats within its breeding range (Shirihai et al. 2001). This may explain its overall higher abundance at 50-km resolution compared to other Mediterranean Sylvia species in the heterogeneous Mediterranean landscapes. In addition, it may be one of the most common bird species (≥ 100 pair/km2) in the most favourable habitats such as in pine and oak open woods with rich understory or shrublands (Aparicio 2016). -

Summary of Evidence of Aggregations of Balearic Shearwaters in the UK up to 2013

JNCC Report No. 642 Summary of evidence of aggregations of Balearic shearwaters in the UK up to 2013 Parsons. M.a, Bingham, C.b, Allcock, Z.c & Kuepfer, A.d November 2019 © JNCC, Peterborough 2019 ISSN 0963-8091 For further information please contact: Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY www.jncc.gov.uk This report should be cited as: Parsons, M., Bingham, C., Allcock, Z. & Kuepfer, A. 2019. Summary of evidence of aggregations of Balearic shearwaters in the UK up to 2013. JNCC Report No. 642, JNCC, Peterborough, ISSN 0963-8091. EQA: This report is compliant with the JNCC Evidence Quality Assurance Policy https://jncc.gov.uk/about-jncc/corporate-information/evidence-quality-assurance/. Affiliations: a JNCC – Inverdee House, Baxter Street, Aberdeen, AB11 9QA b RSPB North Scotland Office - Etive House, Beechwood Park, Inverness, IV2 3BW c Marine Scotland Science - 375 Victoria Road, Aberdeen, AB11 9DB d SAERI - Stanley Cottage North, Ross Road, Stanley, FIQQ 1ZZ, Falkland Islands Summary Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus is listed on Annex I of the EU Birds Directive (2009/147/EC). The EU Birds Directive requires Member States to classify Special Protection Areas (SPA) for birds listed on Annex I of the Directive and for regularly occurring migratory species. Balearic shearwater breeds solely in the western Mediterranean, numbering some 3000 pairs; it is listed by IUCN as Critically Endangered. Movements after the breeding season bring birds into Atlantic waters, primarily off Iberia and western France but also into UK waters, especially those of the English Channel during June to October.