AP Art History 2019 Free-Response Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Chief Turning Point in the Long Course

C H A P T E R 4 T R L he chief turning point in the long course At the same time his social reforms, aimed chie y at of Roman history came in 31 BCE , with the the upper classes, were intended to return his subjects nal collapse of the Roman Republic, and to traditional family values. Laws provided tax breaks its replacement by an Imperial system of for large families and penalized couples who did not Tgovernment. Augustus, the rst emperor, was faced produce children and those who remained unmar- with the task of restoring peace. During his long reign, ried. Adultery became a crime against the state. the spread of economic prosperity produced a hard- Yet despite the success of Augustus’s political and working middle class, loyal to the central government. economic policies, it is doubtful if his moral reform- ing zeal met with more than polite attention. His own daughter and granddaughter, both named Julia, were notorious for their scandalous affairs. To make matters worse, one of the lovers of his daughter Julia was a son of the Emperor’s old enemy, Mark Antony, whose defeat and suicide in 31 BCE had brought the Republic crashing down. Whatever his personal feel- ings, duty compelled Augustus to banish Julia to a remote Mediterranean island. A few years later he had to nd another distant location for the banishment of his granddaughter. He hushed up the details of both scandals, but there was much gossip. Augustus himself created a personal image of ancient Roman frugality and morality, although on his death-bed he gave a clue as to his own more com- plex view of his life. -

1 APAH Daily Calendar 2020 21

APAH CALENDAR 2020 - 21 AP ART HISTORY *subject to constant change CALENDAR & OVERVIEW SUGGESTED SUMMER WORK: KHAN ACADEMY APAH250 IMAGES - APAH WEBSITE LINKS www.pinerichland.org/art BROWSING / SELF - QUIZ *click on APArtHistory tab on Left menu SUMMER SUGGESTED SUMMER WORK: VTHEARLE SUMMER LEARNING FILMS: Expanding upon APAH250 works and deepening RESOURCES VIA PRHS SITE context surrounding works DAILY CLASS READINGS - TO BE DONE BEFORE CLASS *Readings before class: QUIZ: G= Gardner’s Art Through the Ages I will evaluate your retention of class materials periodically in the form of a (DIGITAL EBOOK) POP QUIZ. K= Khan Academy (WEBSITE) Methods may vary: i.e. ‘Plickers’ / Google Quiz They will have a lower relative point value... Aka ‘The Fat these are designed to help guide my instruction ‘APAH 250 Stack’ FORMATIVE (forming understanding) vs. SUMMATIVE (sum end result) CARDS’TIMELINE (hallway) FRQ SIMULATION ESSAY WRITINGS: 3 PER QUARTER = 12 TOTAL FLASH CARDS Details on assignments to follow ‘TIMELINE FLASH CARDS’ for each piece in the 250 IMAGE SET will act GAME (WAR) as Instructional tools to help students learn the material FIELD TRIP (?) ‘HANDS ON’ STUDIO PROJECTS ~$15-$20 FREE CARDS! APRIL, 2021 -More info to come when possible or appropriate ANALYSIS ‘UNIT TESTS’ based on roughly 30 images each METHODS SUMMATIVE Assessment of learning in Units ‘CONCEPT MAPS’ for each piece in the 250 $94 IMAGE SET will act as Instructional tools to VISUAL help students learn the material ‘AP ART HISTORY EXAM’ THURS MAY 6, 2021 12PM shared via -

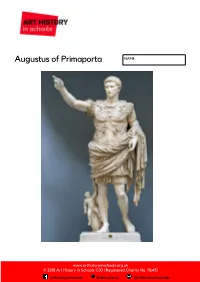

Imperial Image Prescribed Sources: Study Notes 2

Open University Department of Classical Studies Resources for A-Level Classical Civilisation Imperial Image Prescribed Sources: Study Notes 2 Prima Porta Statue Propertius Elegies 3.4 (War and Peace) Propertius Elegies 3.11 (Woman’s Power) Propertius Elegies 3.12 (Chaste and Faithful Galla) Propertius Elegies 4.6. (The Temple of Palatine Apollo) Ovid Metamorphoses 15.745-870 Suetonius Life of Augustus The Forum of Augustus Coin: Octavian/Restorer of laws and rights Coin: Augustus/Comet Coin: Augustus/Gaius and Lucius Caesar Imperial Image Augustus of Prima Porta (Statue) Context: Parthia: What?: Statue of Augustus. • Decoration includes a depiction of the return of When?: c. 20 BC. the Parthian standards. Where?: Found at Villa of Livia at Prima Porta. • Crassus lost these legionary standards to the Material: Marble (may have been a copy of a bronze statue Parthians in 53 BC. 40,000 Roman soldiers were set up elsewhere in Rome). killed. Height: 2.08 metres. • Tiberius negotiated the return of the standards in 20 BC. • The return of the standards was presented as Parthia submitting to Roman control, but Parthia remained an independent state. Stance/Posture: At the Feet: • Standing statue of a male. • Adjacent to the right leg is a cupid riding a • The figure appears young and athletic. dolphin. • Musculature is defined in the arms, legs and • This addition gave stability to the statue. breastplate. • The dolphin recalls Venus’ birth from the sea. • The pose and weight distribution echoes the • Venus was the mother of Aeneas, an ancestor of Doryphoros statue type, an embodiment of the Julian clan. -

PDF of the Notes

Notes __________________________________ These notes aspire neither to completeness nor to the naming of the first respective orig- inator of a thought or a theory. Since this work is more a research report than an academic treatise, such aspirations would actually be neither required nor useful. However, should we have violated any rights of primogeniture, this did not happen intentionally and we hereby apologize beforehand, and promise to mend our ways. We also would like to express our gratitude in advance for any references, tips, or clues sent to us. For abbreviations of collected editions and lexicons, journals and serials, monographs and terms see Ziegler & Sontheimer (1979). For the Greek authors’ names and titles see Liddell & Scott (1996) and for the Latin ones Glare (1996). The Gospel texts translated into English were quoted on the basis of the King James Ver- sion of 1611. In some cases the Revised Standard Version of 1881 and the New American Bible of 1970 were relied on. These three translations often differ from each other considerably. Although they all, even the Catholic one, make use of the original languages rather than the Vulgate as a basis for translation, they have the tendency to read the text of the New Testament according to the current interpreta- tion and to amalgamate it with the Old, so that in critical points the newer transla- tions are overtly conflicting with the Greek original text, arbitrarily interpreting e. g. thalassa, properly ‘sea’, as lake, Christos, ‘Christ’, as Messiah, adapting the orthog- raphy of the proper names in the New Testament to those in the Old, e.g. -

Wilkinson 1 Philip Wilkinson Dr. Berghof HCS17 18 June 2017 The

Wilkinson 1 Philip Wilkinson Dr. Berghof HCS17 18 June 2017 The Chiasmus of the Augustus of Prima Porta and its Propagandistic Utility Ignoring the frequently sidelined chiasmus of the Augustus of Prima Porta risks overlooking the propagandistic utility of the statue that directs thought and discourse by conveying Rome’s progressively expanding military and political power and preservation of past administrative and civil systems. Most importantly, however, the statue accomplishes this with ambiguous connotations so as to understate the impact of the transformation of Roman government into an autocratic and centralized imperial entity. Scholars such as Arias give passing credence to the chiastic shape of the statue (Arias 277) without noticing how it directs the attention of the audience to progressive and conservative themes. Others, such as Pollini, manage to recognize the chiastic form, also referred to as contrapposto, and the manner in which it creates an aesthetic sense of authority and majesty while comparing the statue to the Greek Doryphoros (Pollini 270). Nonetheless, they fail to recognize the chiastic structure of the statue that moves beyond the expression of individualistic emotions and traits to consist of national narratives that critique and glorify the restructuring of Roman civilization’s allocation of martial and bureaucratic power. Moreover, this previously ignored chiasmus goes further by providing the statue’s audience the ability to understand the progressive and conservative themes from a variety of different angles, settings, and directions of viewing the chiasmus. Going even further, the chiasmus also draws attention in towards a metaphor for Rome’s geopolitical empire: the Wilkinson 2 statue’s cuirass, rich in symbolism and icons recounting the recovery of Rome’s sacred standards from Parthia. -

Greek Styles and Greek Art in Augustan Rome: Issues of the Present Versus

Originalveröffentlichung in: James I. Porter (Hrsg.), Classical Pasts. The Classical Traditions of Greece and Rome, Princeton; Oxford 2006, S. 237-269 Chapter 7 GREEK STYLES AND GREEK ART IN AUGUSTAN ROME: ISSUES OF THE PRESENT VERSUS RECORDS OF THE PAST Tonio Holscher Questions Roman art, as we have known since Winckelmann, was to a large extent shaped by “classical pasts,” by the inheritance of Greek art of various periods. In this, visual art corresponds to other domains of Roman culture, which in some respects can be described as a specific successor culture. Archaeological research has observed and evaluated this fact from controversial viewpoints.1 As long as the classical culture of Greece was valued as the highest measure of societal norms and artistic creation, no independent Roman strengths could be recognized in Roman art next to the Greek traditions; this was the basis for the sweeping negative judgment against “the art of the imitators.” Then, from around 1900, beginning with Franz Wickhoff and Alois Riegl,2 as the new archaeological arthistory developed a bold concept of cultural plurality and within this framework discovered and analyzed genuinely Roman forms and structures in visual art, the inherited Greek traditions were often judged to be a cultural burden and an interference in the development of an original Roman art. In neither case was the Greek inheritance seen as a productive element of Roman art. From the negative perspective, Roman art was of inferior impor tance because of its dependence on Greek models. On the positive side, it retained its originality and independence despite its occasional Greek overlay. -

Augustus of Primaporta NAME

NAME: Augustus of Primaporta www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk © 2018 Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 116451 arthistoryinschools @ahischarity @arthistoryinschools Reading and research Please make sure you read/watch and take notes from the following: http://web.mit.edu/21h.402/www/primaporta/ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Augustus_of_Prima_Porta http://mv.vatican.va/4_ES/pages/z-Patrons/MV_Patrons_04_03.html https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/ancient-art-civilizations/roman/early- empire/v/augustus-of-primaporta-1st-century-c-e-vatican-museums https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3yoJhEhkwBY Honour & Fleming ‘A World History of Art’ pp196-197 Summary of Key Facts Date: Who is this a portrait of? Style Size Material Who commissioned it? Where was it found? Art historical terms and concepts To which genre does this work belong? Who is it a portrait of? When did he rule Rome? Where does he look? (gaze) Describe his pose? What is the name given to his raised arm? What is the effect of this gesture? Why does he wear a senator’s robe as well as a military breastplate? Who is the small figure at his ankle? www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk © 2018 Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. 116451 arthistoryinschools @ahischarity @arthistoryinschools Why is this significant? Why is he bare foot? Describe his hair and facial features? Why is this significant? Some parts of this figure are idealised and others realistic. Make sure you know which and why? How big is this figure compared to you? What is the effect of this? www.arthistoryinschools.org.uk © 2018 Art History in Schools CIO | Registered Charity No. -

CLAR 245 (Archaeology of Italy) Instructor: Robyn Le Blanc Rleblanc

CLAR 245 (Archaeology of Italy) Instructor: Robyn Le Blanc [email protected] Murphey #114, T/Th 9:30-11 and by appointment CLAR 245 is a survey of the archaeology of Italy from the Iron Age (ninth century BC) up to the end of the Western Roman Empire (fifth century AD). Particular emphasis will be placed on the processes of urbanization, state formation, and imperial expansion and collapse. Special attention will be given to the contributions of non-Roman cultures to the aforementioned processes, focusing specifically on the Etruscan civilization. The course will offer an overview of Italy's exceptionally rich archaeological record, which includes highlights such as Etruscan tombs, Roman monumental architecture, and early Christian architecture. The archaeological and historical evidence will be combined to reconstruct the long-term development of culture, society, economy, and religion within the geographical context of the Italian peninsula. Required Texts (available at the Friday Center Books and Gifts bookstore) -Fred S. Kleiner,A History of Roman Art, Thomson Wadsworth (ISBN 0-534-63846-5) (Kleiner, on syllabus) -Course Pack, The Archaeology of Italy, UNC Student Stores (CP, on syllabus) -Additional readings in the Lesson folders under “Resources” on Sakai, or found as a link through the UNC e-reserves system. ***Please note that the page numbers assigned for the Kleiner text come from the most recent edition of this book. Grade Distribution Introductory Quiz 5% Midterm 20% Final 20% Memos (best 5 of 6) 25% (or 5% each) Discussion Forum 30% Discussion Each lesson has a start date and a finish date (see the course schedule). -

LAT 253-353.1T1: Latin Studies Abroad: the City of Rome in Roman Literature

LAT 253-353.1T1: Latin Studies Abroad: The City of Rome in Roman Literature Dr. Achim Kopp May Term 2001 217 Knight Hall Telephone: 301-2761 (O); 474-6248 (H) E-Mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.mercer.edu/fll/index.html Texts: Required texts: to be distributed Recommended: Charles E. Bennett. New Latin Grammar . Wauconda, IL: Bolchazy-Carducci, 1998. Charlton T. Lewis. An Elementary Latin Dictionary . Oxford: Oxford UP, 1995. Prerequisite: For LAT 253: LAT 112 or equivalent; For LAT 353: LAT 251 or equivalent Objectives: This course will offer you an introduction to some of the most prominent writers of Roman literature (both poetry and prose), familiarity with a variety of archaeological sites of classical Rome, and first-hand insights into ancient life in Roma aeterna . In addition to literary, cultural, and historical material, the further development of your competency in Latin grammar and vocabulary will be stressed. LAT 253 and LAT 353 differ primarily in the degree of support through commentaries and instructor’s guidance with the Latin texts. Requirements: Meticulous preparation of class material Regular and timely completion of homework assignments Active participation Attendance: You are expected to attend each class session and to contribute constructively to classroom and lab activities, both during our preparatory week on campus and on site in Italy. Evaluation: Class preparation and participation 30 % Quizzes 20 % On-site oral presentation 25 % Final paper 25 % Should you receive failing grades during this course or have trouble with any aspect of this class, you are encouraged to meet with me immediately. 2 Grading System: 90-100 A 70-75 C 86-89 B+ 66-69 D 80-85 B 0-65 F 76-79 C+ Honor Code: The honor code will be firmly followed. -

Roman and Byzantine Architecture Slide 1

U3A, Term 3, 2019 Dr Sharon Mosler EUROPEAN ARCHITECTURE TO 1900 Lecture 2 - Roman and Byzantine Architecture Slide 1: Lectures can be accessed on U3A website: adelaideu3a.org.au Click Course Support, scroll down to 'History of Architecture ’ Sources: *Patrick Nuttgens, Pevsner, Watkin. Also, lectures on YouTube Rome was a city-state in 510BCE, during the flowering of Hellenic culture. As Pericles was introducing democracy in Athens, the Romans were expelling the Etruscans from Italy in its move toward a Republic, then Empire. Before the end of the 2C BCE the great period of Hellenic building activity was over. The leading artists and thinkers that I mentioned last week had all flourished before 200BCE. - The disintegration of the Hellenic achievement in the second and first centuries BCE must be seen in the light of the growing power of Rome. - In Punic Wars 168BCE, Rome secured North Africa and Spain, then Greece 20 years later: Corinth was sacked 146BCE, Athens 60 yrs later A Roman Republic was established around 500BCE, with voting rights similar to those in Greece. The Republic at its height under Julius Caesar, Marcus Aurelius and Augustus Caesar lasted until 27BCE, when Augustus, with absolute power, established the Roman Empire in 27BCE. At that time he ruled 50m people. Augustus of Prima Porta By 30CE the Roman Empire included almost the entire Hellenic world within its orbit, which became the eastern, Greek-speaking half of its empire; although its hold on what are now Iran and Iraq was brief and tenuous, and it never absorbed any part of Afghanistan or Pakistan. -

Embodied Ambiguities on the Prima Porta Augustus Michael Squire

Embodied Ambiguities on the Prima Porta Augustus Michael Squire Of all free-standing Roman Imperial portraits, none is more iconic than the so-called ‘Prima Porta Augustus’, unearthed 150 years ago this month (plate 1).1 Discovered amid the ruins of a private Imperial villa just north of Rome in 1863, restored by no less a sculptor than Pietro Tenerani, and quickly set up in the Musei Vaticani (where the statue has lorded over the Braccio Nuovo ever since), the Prima Porta Augustus epitomizes our collective ideas about both Augustus and the principate that he founded in the late i rst century BCE. Even as early as 1875, Lawrence Alma-Tadema turned to the sculpture as ofi cial Augustan emblem: what better image than the Prima Porta Augustus to conjure up the emperor’s looming presence within an imaginary ‘audience with Agrippa’ (plate 2)?2 For Benito Mussolini in the 1930s, this Imperial image was likewise understood to enshrine the imperial ambitions of Fascist Italy: a bronze copy was duly erected along Rome’s Via dei Fori Imperiali, where it continues to cast its shadow over the imperial fora (plate 3).3 ‘No other image is lodged more i rmly at the heart of today’s scholarship on the art and power of Rome,’ as one textbook puts it, ‘no imperial face more indelibly imprinted on the art historical imagination’.4 But for all our familiarity with the Prima Porta Augustus – and for all the hundreds of books, articles and chapters dedicated to it – there seems to be more to say about both the statue and its original historical context. -

The Military Significance of Venus in Late Republican and Augustan Rome Catherine Julia Smallcombe Bachelor of Arts (Honours)

The Military Significance of Venus in Late Republican and Augustan Rome Catherine Julia Smallcombe Bachelor of Arts (Honours) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2017 School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry i Abstract The Roman goddess Venus is conventionally associated with love, sex, and beauty. However, these were only some of her areas of influence. In reality, her role within the Roman religious system was far more complex and multi-faceted, and was not confined to these associations. Venus, in the Roman mind, bore associations with warfare and military success that were just as prominent. On one hand, this is hardly surprising due to her divine status, especially as one of the Dii Consentes. All Roman deities could be thought of as ‘militaristic’ in some sense. However, even the Romans themselves made a sharp distinction between her role as the goddess of love, and her martial qualities. This indicates both her importance as a martial deity, and the surprising nature of her multi-faceted role in Roman religion. In addition to analysing the development and political advantages of Venus’ martial attributes in Roman religion, this thesis will also offer a survey of the major temples dedicated to Venus in her capacity as a military goddess during the Republican and Augustan periods. An investigation of these temples is a particularly important step towards understanding her influence over military success. Whilst some of the temples have been investigated previously in scholarship, a comprehensive analysis of these sites as evidence for Venus’ role as a martial goddess is still lacking in many cases.