Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

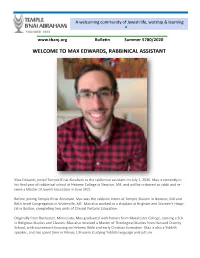

Welcome to Max Edwards, Rabbinical Assistant

A welcoming community of Jewish life, worship & learning www.tbanj.org Bulletin Summer 5780/2020 WELCOME TO MAX EDWARDS, RABBINICAL ASSISTANT Max Edwards joined Temple B’nai Abraham as the rabbinical assistant on July 1, 2020. Max is currently in his final year of rabbinical school at Hebrew College in Newton, MA, and will be ordained as rabbi and re- ceive a Master of Jewish Education in June 2021. Before joining Temple B’nai Abraham, Max was the rabbinic intern at Temple Shalom in Newton, MA and Beth Israel Congregation in Waterville, ME. Max also worked as a chaplain at Brigham and Women’s Hospi- tal in Boston, completing two units of Clinical Pastoral Education. Originally from Rochester, Minnesota, Max graduated with honors from Macalester College, earning a B.A. in Religious Studies and Classics. Max also received a Master of Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School, with coursework focusing on Hebrew Bible and early Christian formation. Max is also a Yiddish speaker, and has spent time in Vilnius, Lithuania studying Yiddish language and culture. LIFE CYCLE EVENTS As of July 14, 2020 MAZEL TOV Jessica & Jay Kooper, son, Ethan, becoming a Bar Mitzvah Andrea Schechter, daughter, Samantha, becoming a Bat Mitzvah Beth & Claude Krause, daughter, Anna, becoming a Bat Mitzvah Ethel & Bob Singer, granddaughter, Anna Krause, becoming a Bat Mitzvah Julie & Matt Kaplan, daughter, Ellie, becoming a Bat Mitzvah Barbara & Cliff Sobel, granddaughter, Ellie Kaplan, becoming a Bat Mitzvah Marlene & Alan Moscowitz, granddaughter, Ruby Belle -

Patent "Trespass" and the Royalty Gap: Exploring the Nature and Impact of Patent Holdout Bowman Heiden

Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal Volume 34 | Issue 2 Article 1 1-3-2018 Patent "Trespass" and the Royalty Gap: Exploring the Nature and Impact of Patent Holdout Bowman Heiden Nicolas Petit Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons, and the Science and Technology Law Commons Recommended Citation Bowman Heiden and Nicolas Petit, Patent "Trespass" and the Royalty Gap: Exploring the Nature and Impact of Patent Holdout, 34 Santa Clara High Tech. L.J. 179 (). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/chtlj/vol34/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara High Technology Law Journal by an authorized editor of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. PATENT “TRESPASS” AND THE ROYALTY GAP: EXPLORING THE NATURE AND IMPACT OF PATENT HOLDOUT Bowman Heiden† & Nicolas Petit‡ This paper studies a problem known as “patent holdout.” Part I reviews the literature on holdout, with a specific emphasis on patents. The literature shows that the ordinary concept of holdout refers to the non-transacting conduct of a property owner, and that “patent trespass” is a better characterization for technology implementers’ attempt to evade concluding licensing agreements with patent owners. Part II proposes a definition and illustrations of patent trespass, relying on the qualitative data collected during interviews with industry stakeholders as well as on an analysis of U.S. -

EXHIBIT a Case 2:14-Cv-00540-JCC Document 1-1 Filed 04/11/14 Page 2 of 6

Case 2:14-cv-00540-JCC Document 1-1 Filed 04/11/14 Page 1 of 6 EXHIBIT A Case 2:14-cv-00540-JCC Document 1-1 Filed 04/11/14 Page 2 of 6 THE WEISER LAW FIRM WWW .WEISERLAWFIRM.COM PENNSYLVANIA CALIFORNIA 22 CASSATT AvE. 12707 HIGH BLUFF DRIVE, SUITE 200 BERWYN, PA 19312 SAN DIEGO, CA 92130 TELEPHONE: (610) 225-2677 TELEPHONE : (858) 794-1441 FACSIMILE : (610) 408-8062 FACSIMILE : (858) 794-1450 March 22, 2013 VIA CERTIFIED MAIL RETURN RECEIPT REQUESTED William H. Gates III Chairman of the Board of Directors Microsoft Corporation One Microsoft Way Redmond, WA 98052-6399 Re: Shareholder Demand Pursuant to Washington Law Dear Mr. Gates: The undersigned firms represent Kim Barovic (the "Stockholder"), a current stockholder of Microsoft Corporation ("Microsoft" or the "Company"). Pursuant to Washington law, we write on behalf of the Stockholder to demand that the Company's Board of Directors (the "Board") take action to remedy breaches of fiduciary duties by certain current and/or former directors and executive officers of the Company, including yourself ("Gates"), Steve Ballmer ("Ballmer"), Dina Dublon ("Dublon"), Maria M. Klawe ("Klawe"), Stephen J. Luczo ("Luczo"), David F. Marquardt ("Marquardt"), Charles H. Noski (''Noski"), Helmut Panke ("Panke"), John W. Thompson ("Thompson"), Peter Klein ("Klein"), Andrew Lees ("Lees"), Eric Rudder ("Rudder"), Brad Smith ("Smith") and B. Kevin Turner ("Turner"). Collectively, the foregoing executive officers and/or directors of the Company will be referred to herein as "Management." As you are aware, by reason of their positions as officers and/or directors of Microsoft and because of their ability to control the business and corporate affairs of Microsoft, members of Management owed and owe Microsoft and its shareholders the fiduciary obligations of good faith, loyalty, and due care. -

Gail Fialkov , Et Al. V. Microsoft Corporation, Et Al. 13-CV-02039

Case 2:13-cv-02039-RSM Document 52 Filed 01/24/14 Page 1 of 41 1 THE HONORABLE RICARDO S. MARTINEZ 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 WESTERN DISTRICT OF WASHINGTON 10 AT SEATTLE 11 GAIL FIALKOV, Individually and on Behalf No. 2:13-cv-02039-RSM 12 of All Others Similarly Situated, CLASS ACTION 13 Plaintiff, CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR 14 vs. VIOLATIONS OF THE FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS 15 MICROSOFT CORPORATION, et al., 16 Defendants. 17 DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 907786_1 CONSOLIDATED COMPLAINT FOR Robbins Geller Rudman & Dowd LLP II VIOLATIONS OF THE FEDERAL SECURITIES 655 West Broadway, Suite 1900, San Diego, CA 92101 Telephone: 619/231-1058 • Fax: 619/231-7423 LAWS (2:13-cv-02039-RSM) Case 2:13-cv-02039-RSM Document 52 Filed 01/24/14 Page 2 of 41 1 Lead Plaintiffs, the Seafarers Pension Plan, the Seafarers Officers and Employees Pension 2 Plan, the United Industrial Workers Pension Plan, the MCS Supplementary Pension Plan and the 3 Oklahoma Firefighters Pension and Retirement System (“Lead Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves 4 and all other persons similarly situated, allege the following based upon personal knowledge as to 5 themselves and their own acts, and information and belief as to all other matters, based upon, inter 6 alia, the investigation conducted by and through their attorneys. 7 NATURE OF THE ACTION 8 1. This is a federal securities class action brought against Microsoft Corporation 9 (“Microsoft” or the “Company”) and three of its senior officers for violations of the Securities 10 Exchange Act of 1934 (the “1934 Act”). -

Jordana George Diss

ABSTRACT Transforming Viscous Data into Liquid Data: How Does Intermediating through Digital Platforms Impact Data? Jordana Jeanne George, Ph.D. Mentor: Dorothy E. Leidner, Ph.D. This study examines how a data platform intermediary enables the evolution of viscous data into liquid data. Viscous, or difficult to use, data is the result of data usage problems that often plague information systems. Data may be viscous because of poor quality, staleness, size issues, unusable formats, missing metadata, unknown history, mysterious provenance, poor access for users, and inability to move data between systems. Viscous data is problematic to use and difficult to incorporate into decision making. On the other hand, liquid data is high quality, formatted to be machine-readable, has provenance and metadata, is easy to move in and out of different systems, is accessible by users, and lends itself well to being used for decision making. Using a longitudinal case study that follows a data platform intermediary startup company from late 2015 to 2018, I break down elements of the platform into data users, data providers, and data intermediaries. Using a lens from the Community of Practice literature, I show how social learning, data wrangling, data complementing, and data liberalizing on a digital data platform transform data from viscous to liquid. This work contributes by providing a different perspective to data management, a means to address a dearth of data skills, and a way to make data more usable for both individuals and institutions. Transforming Viscous Data into Liquid Data: How Does Intermediating through Digital Platforms Impact Data by Jordana J. -

When Standards Collide with Intellectual Property: Standard Setting Organizations, Technology, and Microsoft V

When Standards Collide with Intellectual Property: Standard Setting Organizations, Technology, and Microsoft v. Motorola Cynthia Laury Dahl University of Pennsylvania Law School January 2018 www.codes-and-standards.org This material was developed under the auspices of the Penn Program on Regulation using federal funds under awards 70NANB15H343 and 70NANB15H344 from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), U.S. Department of Commerce. Any statements, findings, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Penn Program on Regulation, the University of Pennsylvania, NIST, or the U.S. Department of Commerce. When Standards Collide with Intellectual Property: Standard Setting Organizations, Technology, and Microsoft v. Motorola Cynthia Laury Dahl In the summer of 2010, Motorola Inc. (“Motorola”) was in turmoil. After a flurry of successes in 2004, when it launched its Razr mobile phone, Motorola was most recently reeling from a $4.3 billion loss to the company between 2006 and 2009. It was looking forward to spinning off its faltering mobile phone and cable equipment divisions into a second publicly owned company called Motorola Mobility (“MM”), which would operate separately from the more traditionally stable public safety division. Although MM had an uncertain future, parent Motorola would leave MM with a solid and valuable legacy: Due to Motorola’s decades-old tradition of research and development in all realms of technology, MM would inherit a patent portfolio of over 17,000 active patents after the split.1 Motorola’s biggest competitors in 2010 were Apple and Samsung. But while those competitors were debuting devices that incorporated increasingly innovative technology, Motorola’s devices did not even incorporate many of the company’s own patented inventions. -

Summary 1 of 24

"ISRAEL M. KIRZNER AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MARKET PROCESS" A DISCUSSION HELD IN MARCH, 2017. Online: <http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/lm-kirzner> Ebooks: <http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2730>. Israel M. Kirzner Summary In this Liberty Matters online discussion Peter Boettke of George Mason University examines Israel Kirzner’s insights into the rivalrous nature of competitive behavior and the market process, his analysis of market theory and the operation of the price system, the institutional environment that enables a market economy to realize mutual gains from trade and to continuously discover gains from innovation, and to produce a system characterized by economic growth and wealth creation. Boettke concludes by arguing that Kirzner has done more than nearly any other living modern economist to improve our understanding of competitive behavior and the operation of the price system in a market economy. Boettke is joined in the discussion by Peter G. Klein, professor of entrepreneurship at Baylor University’s Hankamer School of Business, Mario Rizzo, professor of economics at New York University, and Frédéric Sautet, associate professor at The Catholic University of America. Boettke and Sautet are the editors of Liberty Fund’s 10 volume The Collected Works of Israel M. Kirzner. 1 of 24 About Liberty Matters and the Online Library of Liberty can be found at <http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2516>. “Liberty Matters” is a project of Liberty Fund, Inc. which is part of the Online Library of Liberty website. Every two months we ask a leading Copyright & Fair Use Statement scholar to present an argument on a particular topic “pertaining to liberty” in a “Lead Essay” and to develop this argument at some length. -

Microsoft Reports Record Fourth-Quarter Results Broad-Based Strength Drives Double-Digit Revenue Growth in All Business Segments

Microsoft_Investor_Relations_News_Release Microsoft Reports Record Fourth-Quarter Results Broad-based strength drives double-digit revenue growth in all business segments REDMOND, Wash. — July 22, 2010 — Microsoft Corp. today announced record fourth-quarter revenue of $16.04 billion for the quarter ended June 30, 2010, a 22% increase from the same period of the prior year. Operating income, net income and diluted earnings per share for the quarter were $5.93 billion, $4.52 billion and $0.51 per share, which represented increases of 49%, 48% and 50%, respectively, when compared with the prior year period. “This quarter’s record revenue reflects the breadth of our offerings and our continued product momentum,” said Peter Klein, chief financial officer. “The revenue growth, combined with our ongoing cost discipline, helped us achieve another quarter of margin expansion.” Product momentum continued during the quarter with the successful launch of Office 2010 and strong performance from existing products including Windows 7, which has sold more than 175 million licenses to date, Windows Server, Xbox, and Bing, which achieved its 13th consecutive month of share gain. “We saw strong sales execution across all of our businesses, particularly in the enterprise with Windows 7 and Office 2010,” said Kevin Turner, chief operating officer. “Our transition to cloud services is well underway with offerings like Windows Azure and our Business Productivity Online Services, and we look forward to continuing our product momentum this fall with the upcoming launches of Windows Phone 7 and Xbox Kinect.” For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2010, Microsoft reported record revenue of $62.48 billion, a 7% increase from the prior year. -

Microsoft Corporation

f UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 2012 OR ! TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition Period From to Commission File Number 0-14278 MICROSOFT CORPORATION WASHINGTON 91-1144442 (STATE OF INCORPORATION) (I.R.S. ID) ONE MICROSOFT WAY, REDMOND, WASHINGTON 98052-6399 (425) 882-8080 www.microsoft.com/investor Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: COMMON STOCK, $0.00000625 par value per share NASDAQ Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: NONE Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes No ! Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes ! No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. Yes No ! Indicate by check mark whether the registrant has submitted electronically and posted on its corporate Web site, if any, every Interactive Data File required to be submitted and posted pursuant to Rule 405 of Regulation S-T (§232.405 of this chapter) during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to submit and post such files). -

YOU Gave Generously: Corporations Every Year, United Way of King County Recognizes Outstanding Workplace Campaigns with the Spirit of Caring Awards

START IT S W I TH 2009-2010 SPIRIT OF CARING AwaRDS Costco Wholesale takes top honors at United Way’s Spirit of Caring Celebration YOU gave generously: Corporations Every year, United Way of King County recognizes outstanding workplace campaigns with the Spirit of Caring Awards. Costco Wholesale received the 2009-2010 Spirit of Puget Sound Award, King County’s highest achievement in corporate philanthropy. It honors outstanding community involvement, sustained campaign excellence and the promotion of volunteerism. For the 2009-2010 campaign season, the employees of Costco Wholesale showed incredible heart and boundless generosity. Chairman Jeff Brotman’s and CEO Jim Sinegal’s strong leadership and commitment to United Way of King County resonated throughout the company, and made this campaign year an exceptional success. Leadership Giving (gifts of $1,000 and above) jumped 7 percent company-wide, and overall participation was 84 percent—a 33 percent increase. Adding to Costco’s campaign success was its innovative new Express Pledge System. This point-of-sale pledge system for employees enabled gifts to go directly to United Way of King County in $5 increments, which generated nearly $60,000. Lauren Kutschka accepted the award on Costco’s behalf In all, Costco’s Northwest region raised $3.7 million for United Way of King County during a superb campaign. Costco employees also gave generously of their time, volunteering on Day of Caring. Executive of the Year Award Most Significant Increase Award Recognizing an exceptional level of support for United Way For exceptional campaign growth of King County by a top executive Charter Bank Sandy Gregory, Seattle Seahawks TOP 40 SUPPORTERS OF UNITED way OF KING COUNTY First Place School Companies listed gave between July 1, 2009 and June 30, 2010 Ambassador of the Year INCA Engineers Inc. -

Why Not Tell the Truth: Deceptive Practices and the Financial Meltdown. Charles W

Loyola University Chicago, School of Law LAW eCommons Faculty Publications & Other Works 2010 Why Not Tell the Truth: Deceptive Practices and the Financial Meltdown. Charles W. Murdock Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/facpubs Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Murdock, Charles W., Why Not Tell the Truth: Deceptive Practices and the Financial Meltdown, 41 Loy. U. Chi. L.J. 801 (2010). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Why Not Tell the Truth?: Deceptive Practices and the Economic Meltdown Charles W. Murdock* "Beware of Geeks Bearing Formulas."' 2 "[For] too long there's been a culture of anything goes." 3 "What is required of us now is a new era of responsibility." I. INTRODUCTION The above statements, one by a distinguished businessman and the others by our new president and his chief of staff, bear directly on the subject of this Article. Today we are witnessing a crisis caused by economic formulae developed without a responsible exercise of judgment and, in many instances, with a shocking disregard for the truth. The virtue of truthfulness is not just some abstract moral principle. Rather, it is a critical component of a well functioning society. As the current situation demonstrates, the lack of regard for truthfulness can have disastrous consequences, not just for our own country, but around the world. -

Volume 44 - Issue 02 - Friday, September 19, 2008

Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Rose-Hulman Scholar The Rose Thorn Archive Student Newspaper Fall 9-19-2008 Volume 44 - Issue 02 - Friday, September 19, 2008 Rose Thorn Staff Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn Recommended Citation Rose Thorn Staff, "Volume 44 - Issue 02 - Friday, September 19, 2008" (2008). The Rose Thorn Archive. 131. https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rosethorn/131 THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS ROSE-HULMAN REPOSITORY IS TO BE USED FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP, OR RESEARCH AND MAY NOT BE USED FOR ANY OTHER PURPOSE. SOME CONTENT IN THE MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT. ANYONE HAVING ACCESS TO THE MATERIAL SHOULD NOT REPRODUCE OR DISTRIBUTE BY ANY MEANS COPIES OF ANY OF THE MATERIAL OR USE THE MATERIAL FOR DIRECT OR INDIRECT COMMERCIAL ADVANTAGE WITHOUT DETERMINING THAT SUCH ACT OR ACTS WILL NOT INFRINGE THE COPYRIGHT RIGHTS OF ANY PERSON OR ENTITY. ANY REPRODUCTION OR DISTRIBUTION OF ANY MATERIAL POSTED ON THIS REPOSITORY IS AT THE SOLE RISK OF THE PARTY THAT DOES SO. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspaper at Rose-Hulman Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rose Thorn Archive by an authorized administrator of Rose-Hulman Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. T HE R OSE T HORN R OSE -H ULMAN I NSTITUTE OF T ECHNOLOGY T ERRE H AUTE , I NDIANA FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER 19, 2008 ROSE-HULMAN.EDU/THORN/ VOLUME 44, ISSUE 2 VX is gone for good News Briefs Noel Spurgeon p r o c e s s e s By Andrew Klusman Guest Writer like these are chal- n August 8, 2008, lenging be- Original Mozart music the US Army con- cause of the Ofirmed that the last need to pro- found in France ton container of nerve agent vide maxi- An original piece of music written by VX had been destroyed at mum pro- Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the famous the Newport Chemical De- tection for Classical composer, was found in a library pot in Newport, Ind.