University-Urban Interface Program. a University and Its Community Confront Problems and Goals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

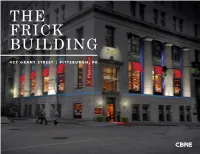

The Frick Building

THE FRICK BUILDING 437 GRANT STREET | PITTSBURGH, PA HISTORIC BUILDING. PRIME LOCATION. THE FRICK BUILDING Located on Grant Street across from the Allegheny County court house and adjacent to Pittsburgh City Hall, the Frick Building is just steps away from many new restaurants & ongoing projects and city redevelopments. The Frick Building is home to many creative and technology based fi rms and is conveniently located next to the Bike Pittsburgh bike rental station and Zipcar, located directly outside the building. RESTAURANT POTENTIAL AT THE HISTORIC FRICK BUILDING Grant Street is becoming the city’s newest restaurant district with The Commoner (existing), Red The Steak- house, Eddie V’s, Union Standard and many more coming soon Exciting restaurants have signed on at the Union Trust Building redevelopment, Macy’s redevelopment, Oliver Building hotel conversion, 350 Oliver development and the new Tower Two-Sixty/The Gardens Elevated location provides sweeping views of Grant Street and Fifth Avenue The two levels are ideal for creating a main dining room and private dining facilities Antique elevator, elegant marble entry and ornate crown molding provide the perfect opportunity to create a standout restaurant in the “Foodie” city the mezzanine AT THE HISTORIC FRICK BUILDING 7,073 SF available within a unique and elegant mezzanine space High, 21+ foot ceilings Multiple grand entrances via marble staircases Dramatic crown molding and trace ceilings Large windows, allowing for plenty of natural light Additional space available on 2nd floor above, up to 14,000 SF contiguous space Direct access from Grant Street the mezzanine AT THE HISTORIC FRICK BUILDING MEZZANINE OVERALL the mezzanine AT THE HISTORIC FRICK BUILDING MEZZANINE AVAILABLE the details AT THE HISTORIC FRICK BUILDING # BIGGER. -

2019 State of Downtown Pittsburgh

20 STATE OF DOWNTOWN PITTSBURGH19 TABLE OF CONTENTS For the past eight years, the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership has been pleased to produce the State of Downtown Pittsburgh Report. This annual compilation and data analysis allows us to benchmark our progress, both year over year and in comparison to peer cities. In this year’s report, several significant trends came to light helping us identify unmet needs and better understand opportunities for developing programs and initiatives in direct response to those challenges. Although improvements to the built environment are evident in nearly every corridor of the Golden Triangle, significant resources are also being channeled into office property interiors to meet the demands of 21st century companies and attract a talented workforce to Pittsburgh’s urban core. More than $300M has been invested in Downtown’s commercial office stock over the 4 ACCOLADES AND BY THE NUMBERS last five years – a successful strategy drawing new tenants to Downtown and ensuring that our iconic buildings will continue to accommodate expanding businesses and emerging start-ups. OFFICE, EMPLOYMENT AND EDUCATION Downtown experienced a 31% growth in residential population over the last ten years, a trend that will continue with the opening 6 of hundreds of new units over the next couple of years. Businesses, from small boutiques to Fortune 500 companies, continued to invest in the Golden Triangle in 2018 while Downtown welcomed a record number of visitors and new residents. HOUSING AND POPULATION 12 Development in Downtown is evolving and all of these investments combine to drive the economic vitality of the city, making Downtown’s thriving renaissance even more robust. -

Pittsburgh, Pa), Photographs, 1892- 1981 (Bulk 1946-1965)

Allegheny Conference On Community Development Page 1 Allegheny Conference On Community Development (Pittsburgh, Pa), Photographs, 1892- 1981 (bulk 1946-1965) Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Archives MSP# 285 30 boxes (Boxes 1-22 Prints, Boxes 23-28 Negatives, Box 28 Transparencies, Boxes 29-30 Oversized Prints) Table of Content: Historical Note page 1 Scope and Content Note page 2 Series I: Prints page 2 Sub-series: Aviation page 3 Sub-series: Buildings page 3 Sub-series: Culture page 3 Sub-series: Education page 3 Sub-series: Golden Triangle page 4 Sub-series: Health & Welfare page 4 Sub-series: Highways page 4 Sub-series: Historical page 4 Sub-series: Housing page 4 Sub-series: Miscellaneous page 5 Sub-series: PA Pitt Partner’s Program page 5 Sub-series: Personnel page 5 Sub-series: Publications page 5 Sub-series: Recreation page 6 Sub-series: Research page 6 Sub-series: Smoke Control page 6 Sub-series: Stadiums page 6 Sub-series: Transportation page 6 Sub-series: Urban Redevelopment page 7 Series II: Negatives page 7 Sub-Series: Glass Plate Negatives page 7 Series III: Transparencies page 7 Series IV: Oversized Prints & Negatives page 7 Provenance page 8 Restrictions and Separations page 8 Catalog Entries page 8 Container List page 10 Series I: Prints page 10 Sub-series: Aviation page 10 Sub-series: Buildings page 10 Sub-series: Culture page 14 Allegheny Conference On Community Development Page 2 Sub-series: Education page 16 Sub-series: Golden Triangle page 20 Sub-series: Health & Welfare page 22 Sub-series: Highways page -

Pittsburgh, PA), Records, 1920-1993 (Bulk 1960-90)

Allegheny Conference On Community Development (Pittsburgh, PA), Records, 1920-1993 (bulk 1960-90) Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania Archives MSS# 285 377 boxes (Box 1-377); 188.5 linear feet Table of Contents Historical Note Page 2 Scope and Content Note Page 3 Series I: Annual Dinner Page 4 Series II: Articles Page 4 Series III: Community Activities Advisor Page 4 Series IV: Conventions Page 5 Series V: Director of Planning Page 5 Series VI: Executive Director Page 5 Series VII: Financial Records Page 6 Series VIII: Highland Park Zoo Page 6 Series IX: Highways Page 6 Series X: Lower Hill Redevelopment Page 6 Series XI: Mellon Square Park Page 7 Series XII: News Releases Page 7 Series XIII: Pittsburgh Bicentennial Association Page 7 Series XIV: Pittsburgh Regional Planning Association Page 7 Series XV: Point Park Committee Page 7 Series XVI: Planning Page 7 Series XVII: Recreation, Conservation and Park Council Page 8 Series XVIII: Report Library Page 8 Series XIX: Three Rivers Stadium Page 8 Series XX: Topical Page 8 Provenance Page 9 Restrictions and Separations Page 9 Container List Series I: Annual Dinner Page 10 Series II: Articles Page 13 Series III: Community Activities Advisor Page 25 Series IV: Conventions Page 28 Series V: Director of Planning Page 29 Series VI: Executive Director Page 31 Series VII: Financial Records Page 34 Series VIII: Highland Park Zoo Page 58 Series IX: Highways Page 58 Series X: Lower Hill Page 59 Series XI: Mellon Square Park Page 60 Series XII: News Releases Page 61 Allegheny Conference On Community -

PHLF News Publication

Protecting the Places that Make Pittsburgh Home Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Nonprofit Org. 1 Station Square, Suite 450 U. S. Postage Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1134 PAID www.phlf.org Pittsburgh, PA Address Service Requested Permit No. 598 PHLF News Published for the members of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation No. 162 March 2002 In this issue: 6 Awards in 2001 10 Richard King Mellon Foundation Gives Major Grant to Landmarks’ Historic Rural Preservation Program 16 Remembering Frank Furness 19 Solidity & Diversity: Ocean Grove, New Jersey More on Bridges Bridges, roads, and buildings were ablaze in light in 1929, when Pittsburgh joined cities across the nation in celebrating the Pittsburgh’s Bridges: fiftieth anniversary of the lightbulb. Architecture & Engineering Walter C. Kidney to Landmarks to pay for the lighting of The following excerpt from a recent Duquesne Light Funds the Roberto Clemente Bridge. The grant review in The Journal of the Society may also be used for certain mainte- for Industrial Archaeology might nance costs so taxpayers will not have to encourage you to buy Walter Bridge Lighting bear all future maintenance costs. Kidney’s book on bridges if you We have appointed a Design Advisory have not already done so (see page 9 Committee, headed by our chairman In the summer, the Roberto Clemente Bridge will be lighted, thanks to a generous for book order information): grant from Duquesne Light Company and the cooperative efforts of Landmarks, Philip Hallen, that will work in cooperation with the Urban Design For his book, Kidney was able to the Riverlife Task Force, Councilman Sala Udin, and many interested parties. -

Regional Operations Plan – 2019

2019 Regional Operations Plan for Southwestern Pennsylvania Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission Two Chatham Center – Suite 500 112 Washington Place Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Voice 412.391.5590 Fax 412.391.9160 [email protected] www.spcregion.org July, 2019 Southwestern Pennsylvania Commission 2019 Officers Chairman: Larry Maggi Vice Chairman: Rich Fitzgerald Secretary-Treasurer: Tony Amadio Executive Director: James R. Hassinger Allegheny County Armstrong County Beaver County Butler County Rich Fitzgerald Darin Alviano Tony Amadio Kevin Boozel Lynn Heckman Pat Fabian Daniel Camp Kim Geyer Clifford Levine Richard Palilla Sandie Egley Mark Gordon Robert J. Macey Jason L. Renshaw Kelly Gray Richard Hadley David Miller George J. Skamai Charles Jones Leslie A. Osche Fayette County Greene County Indiana County Lawrence County Joe Grata Dave Coder Michael Baker Steve Craig Fred Junko Jeff Marshall Sherene Hess Robert Del Signore Dave Lohr Robbie Matesic Mark Hilliard James Gagliano Vincent A. Vicites Archie Trader Rodney D. Ruddock Amy McKinney Angela Zimmerlink Blair Zimmerman Byron G. Stauffer, Jr. Daniel J. Vogler Washington County Westmoreland County City of Pittsburgh Pennsylvania Department Larry Maggi Charles W. Anderson Scott Bricker of Transportation (2 Votes) Scott Putnam Robert J. Brooks Rev. Ricky Burgess Joseph Dubovi Harlan Shober Tom Ceraso William Peduto Kevin McCullough Diana Irey-Vaughan Gina Cerilli Mavis Rainey Cheryl Moon-Sirianni Christopher Wheat Ted Kopas Aurora Sharrard Larry Shifflet Joe Szczur Governor's Office Pennsylvania Department Port Authority of Transit Operators Committee Jessica Walls-Lavelle of Community & Allegheny County (1 Vote) Sheila Gombita Economic Development Katharine Kelleman Johnna Pro Ed Typanski Federal Highway Federal Transit U.S. Environmental Federal Aviation Administration* Administration* Protection Agency* Administration* Alicia Nolan Theresa Garcia-Crews Laura Mohollen U. -

A Golden Triangle

2 DOWNTOWN: A GOlDeN TriANGle © 2009 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. 41 fig. 2.1 The Golden Triangle f the various claims about who first likened downtown Pittsburgh to a Golden Triangle, one has primacy. After the Great Fire of 1845 ravaged the city’s core, Mayor William Howard is said to have O declared, “We shall make of this triangle of blackened ruins a golden triangle whose fame will endure as a priceless heritage.” The Golden Triangle nickname was already well established locally by 1914, when an article in the Saturday Evening Post gave it national publicity. The nickname was a good fit because the 255 acres bounded by Grant Street and the Allegheny and Monongahela rivers must count among the most gilded in the United States, having generated immense wealth. The Triangle constitutes a city in itself, with retail strips on Wood and Smithfield streets and Forbes and Fifth avenues, a government center on Grant, two churches and the Duquesne Club on Sixth Avenue, and extensive cultural facilities set among the cast-iron fronts and loft buildings on Penn and Liberty avenues. The compactness of the Golden Triangle is a marvel in its own right: no two of its points are more than a fifteen-minute walk apart. The subway route from Grant Street to Gateway Center is so tiny that its entire length is shorter than the subway platform beneath Times Square in New York. © 2009 University of Pittsburgh Press. All rights reserved. Being so small, downtown Pittsburgh is the preserve of pedestrians. In winter, they tend to stay indoors by using the subway and the tunnels, atri- ums, and interior streets of the new buildings. -

Report, Our Seventh Annual Publication Compiling Relevant, Consistent and Reliable Data About Our Greater Downtown Neighborhood

8 STATE 1 OF 0 DOWNTOWN 2 PITTSBURGH 03 ACCOLADES BY THE NUMBERS 05 OFFICE, EMPLOYMENT & EDUCATION 11 HOUSING & POPULATION 15 RESTAURANTS & RETAIL 19 HOTEL, CULTURE & ENTERTAINMENT 23 TRANSPORTATION & CONNECTIVITY 27 PLACE & ENVIRONMENT 31 DOWNTOWN DEVELOPMENT 37 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership is pleased to deliver the 2018 State of Downtown Pittsburgh report, our seventh annual publication compiling relevant, consistent and reliable data about our Greater Downtown neighborhood. More and more we see a shift in the types of businesses interested in calling Downtown home. Next generation commerce – from technology based Evoqua and Pineapple Payments to highly skilled and talented local producers and retailers like Moop, Steel City, and love, Pittsburgh – is seeking creative space, offices, and brick-and-mortar storefronts and finding them in unusual locations unique to our Downtown neighborhood. Entrepreneurs and startups utilize co-working spaces like Industrious and Level Office to develop and strengthen while local entities like Beauty Shoppe find value in Downtown for expansion. The desire and interest for authentic products is evident and the realization of Downtown as a hub for tech-savvy business and growth is equally assured. The PDP will continue exploring ways to support this renaissance reprise while providing additional opportunities for these talented businesses to expand and residents to become an even more essential part of this community. A critical mass of residential, commercial, cultural, and recreational activities is vital to ensuring a happy, healthy base of workers and we believe that Downtown is uniquely positioned to be the premier neighborhood that invites and welcomes all. This edition of the State of Downtown Pittsburgh celebrates the solid foundation of strong economic development work across many industries underpinning the growth of a vibrant Downtown Pittsburgh. -

Building an Equitable New Normal: Responding to the Crises of Racist Violence and COVID-19,” Gender Equity Commission, City of Pittsburgh

Note From the Commission Chair … The COVID-19 pandemic has caused enormous misery and harm to people across the globe and here in Pittsburgh. We grieve the lives lost and mourn the economic and social toll of the virus. We also acknowledge that the impact of the crisis has not been equal on all: in many ways, the pandemic has split wide-open the long-standing inequalities in our city. The virus did not create new inequalities, but it has disproportionately impacted our most vulnerable and marginalized communities. At the same time, the much older “virus” of white supremacy and structural racism has infected our country for more than 400 years. We denounce the brutal police killing of George Floyd. We denounce the recent murders of Breonna Taylor, Nina Pop, and many other Black and women of color. And we condemn the historical erasure of Black women and girls, including trans and gender diverse people, killed by violent practices and policies that have been normalized for far too long in our culture. In Pittsburgh, those protesting police violence in this moment have been forced to risk contracting the corona virus while facing additional police violence. We also see that our frontline and “essential” workers are so often women and people of color who are jeopardizing their lives, frequently because they can’t jeopardize their livelihoods. The pandemic has exposed the massive quantity of unpaid care-giving and domestic labor that falls disproportionately on women. It has deepened the crisis of gender and sexual violence, including for trans women of color who were already experiencing some of the highest rates of assault and murder. -

Downtown Pittsburgh Renaissance and Renewal

one Downtown Pittsburgh renaissance and renewal Edward K. Muller Q Despite a metropolitan population in decline since 1960, steady suburban- ization, and the loss of several major corporate headquarters in the past two decades, downtown Pittsburgh remains a vigorous and vital central business district, in marked contrast to the downtowns of many older mid-level cities. Office occupancy rates remain stable, and the rehabilitation of older buildings indicates a steady demand for office space. Cultural attractions and tourism are increasing; hotel space is being expanded. Although retailers struggle to compete with suburban malls, they remain an integral part of the downtown business mix. Parking is tight, traffic congestion is a constant annoyance, loft housing is growing in popularity, and the boundaries of downtown are expanding, albeit slowly, to the east and north across the Allegheny River. Several factors particular to Pittsburgh helped to sustain the Golden Triangle, as downtown is frequently called, during the post–World War II era when the downtowns of other cities were rapidly deteriorating. But, most notably, active involvement of the civic leadership—both public and private—through programs of urban renaissance, renewal, and redevelopment has played a major role in maintaining the downtown’s viability. Postwar Renaissance In 1943 when Pittsburgh’s leaders turned their attention, however briefly, away from the war and toward the future of their city, they despaired over what they saw. Despite the concentration of powerful industrial corporations 8 EDWARD K. MULLER in the region, a severely degraded environment so diminished the quality of life that corporations not only found it increasingly difficult to recruit and retain topflight personnel but some even considered moving their headquar- ters out of Pittsburgh to New York City. -

The Pittsburgh Downtown Plan a Blueprint for the 21St Century Contents

The Pittsburgh Downtown Plan A blueprint for the 21st century Contents Overview Focus Areas Districts Appendix This Plan is a flexible, mar- Each Focus Area section out- The following studies and ket-based framework for lines general strategies and reports contribute to the final Downtown development specific district proposals. Plan and are available in the over the next ten years. Adobe Acrobat® format on the accompanying CD- Why Now? . 3 Retail & Attractions . 12 ROM. Project Scope. 3 An Action Plan and Its Implications The Development Strategy— Fifth & Forbes . 65 Establishing the Business Retail Market Analysis of Downtown Pittsburgh Pittsburgh 24-Hour City . 4 Climate . 18 Gateway . 69 Summary of Findings: Phase One Sixth Street Connection . 73 Downtown Entertainment and Attractions (Present to 2001) . 5 Housing . 24 North Shore . 77 Summary of Findings: Plan The North Shore’s Business Climate Second Act . 6 Cultural District . 84 A blueprint for the 21st century Downtown Housing Action Plan The Planning Process . 7 Convention Center . 88 and Companion Tables Institutions. 30 Strip District. 91 Urban Design Guidelines Streetscape Standards Catalog South Shore . 95 Adaptive Reuse Building Code Study First Side. 98 Transportation . 35 Transportation Abstract Grant Street Corridor. 101 Downtown Transit and Retail Civic Arena / Lower Hill . 104 Relationship Urban The Relationship between Transit Design . 54 and Major Downtown Attractions Intercept Study of Shopping and Entertainment Patterns Phone Study of Shopping and Entertainment Patterns THE PITTSBURGH DOWNTOWN PLAN Page 3 c Overview Why Now? It’s been more than 35 years since Pittsburgh last undertook a comprehensive Downtown planning process. Since then, the city and region have undergone major economic View of Pittsburgh from Mount and social changes, including Washington in 1942 the diversification of its employment base, from manufacturing to one driven by tech- nologies and knowledge-based enterprise. -

Postcard Collection Library

Revised January 22, 2016 General Postcard Collection (GPCC) (See also: MSS#177 Papers of Margaret Deland MSS#389 Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh MSS#573 Rose Kaplan Papers MSS#66 Papers of the McClelland Family MSS#237 Papers of William M. McKillop MSS#860 Park-Kelly Family Papers and Photographs MSS#571 Paslawsky Family Papers and Photographs MSS#301 Richard E. Rauh Papers MSS#335 Papers of Aaronel deRoy Gruber MSS#204 Papers of Bill Green MSS#760 Britta C. Dwyer Papers MSS#773 Dwyer Family Papers MSS#938 Grete Zacharias Papers PSS#035 Howard Etzel Photograph Collection MFF#2944 Postcard Scrapbook of Dr. B. Heintzman, 1929 Acc. 1994.0001 Acc. 1994.0255 Acc. 1994.0285 Acc. 1995.0013 Acc. 1995.0014 Acc. 1996.0024 – Pittsburgh and Kittaning, Pa. postcards Acc. 1996.0084 Acc. 1996.0155 Acc. 1997.0040 Acc. 1997.0042 – Views of Pittsburgh Acc. 1997.0065 – Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania postcards Acc. 1997.0104 – Pittsburgh and Allegheny postcard album 1902 Acc. 1997.0201 – View of Pittsburgh 1849 Acc. 1997.0228 Acc. 1999.0163 Acc. 2001.0195 Acc. 2001.0243 Acc. 2002.0022 Acc. 2003.0186 Acc. 2004.0074 Acc. 2006.0096 Acc. 2008.0126 Acc. 2009.0170 Acc. 2010.0085 Postcard Collection Inventory, Page # 2 of 81 Acc. 2011.0171 – Interesting Views of Pittsburgh postcard book Acc. 2011.0218 – Pittsburgh and Western Pa. Acc. 2011.0292 – Gateway Center, Point, Downtown Acc. 2014.0017) (Book Resources: Search Postcard History Series in catalog Greetings from Pittsburgh: A Picture Postcard History/Ralph Ashworth - F159.3.P643 A84 1992 q A Pennsylvania Album: picture postcards 1900-1930/George Miller - F150.M648 long Riverlife: Postcards from the Rivers/Riverlife Task Force – HT177 .P5 P6 2002 long Box 1 Pittsburgh Aviaries Conservatory Aviary Churches All Saints Episcopal- Allegheny Bethany Evangelical Lutheran- East Liberty Bethel Presbyterian Calvary Episcopal – Shady/Walnut Calvary United Methodist – North Side Christ Evangelical Lutheran-East End Christ Church of the Ascension – Ellsworth & Neville Christ M.E.