Accents and Paradoxes of Modern Philology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Network Map of Knowledge And

Humphry Davy George Grosz Patrick Galvin August Wilhelm von Hofmann Mervyn Gotsman Peter Blake Willa Cather Norman Vincent Peale Hans Holbein the Elder David Bomberg Hans Lewy Mark Ryden Juan Gris Ian Stevenson Charles Coleman (English painter) Mauritz de Haas David Drake Donald E. Westlake John Morton Blum Yehuda Amichai Stephen Smale Bernd and Hilla Becher Vitsentzos Kornaros Maxfield Parrish L. Sprague de Camp Derek Jarman Baron Carl von Rokitansky John LaFarge Richard Francis Burton Jamie Hewlett George Sterling Sergei Winogradsky Federico Halbherr Jean-Léon Gérôme William M. Bass Roy Lichtenstein Jacob Isaakszoon van Ruisdael Tony Cliff Julia Margaret Cameron Arnold Sommerfeld Adrian Willaert Olga Arsenievna Oleinik LeMoine Fitzgerald Christian Krohg Wilfred Thesiger Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant Eva Hesse `Abd Allah ibn `Abbas Him Mark Lai Clark Ashton Smith Clint Eastwood Therkel Mathiassen Bettie Page Frank DuMond Peter Whittle Salvador Espriu Gaetano Fichera William Cubley Jean Tinguely Amado Nervo Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay Ferdinand Hodler Françoise Sagan Dave Meltzer Anton Julius Carlson Bela Cikoš Sesija John Cleese Kan Nyunt Charlotte Lamb Benjamin Silliman Howard Hendricks Jim Russell (cartoonist) Kate Chopin Gary Becker Harvey Kurtzman Michel Tapié John C. Maxwell Stan Pitt Henry Lawson Gustave Boulanger Wayne Shorter Irshad Kamil Joseph Greenberg Dungeons & Dragons Serbian epic poetry Adrian Ludwig Richter Eliseu Visconti Albert Maignan Syed Nazeer Husain Hakushu Kitahara Lim Cheng Hoe David Brin Bernard Ogilvie Dodge Star Wars Karel Capek Hudson River School Alfred Hitchcock Vladimir Colin Robert Kroetsch Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai Stephen Sondheim Robert Ludlum Frank Frazetta Walter Tevis Sax Rohmer Rafael Sabatini Ralph Nader Manon Gropius Aristide Maillol Ed Roth Jonathan Dordick Abdur Razzaq (Professor) John W. -

Udc 930.85:78(477.83/.86)”18/19” Doi 10.24919/2519-058X.19.233835

Myroslava NOVAKOVYCH, Olha KATRYCH, Jaroslaw CHACINSKI UDC 930.85:78(477.83/.86)”18/19” DOI 10.24919/2519-058X.19.233835 Myroslava NOVAKOVYCH PhD hab. (Art), Associate Professor, Professor of the Departmentof Musical Medieval Studies and Ukrainian Studies.Mykola Lysenko Lviv National Music Academy, 5 Ostapa Nyzhankivskoho Street, Lviv, Ukraine, postal code 79005 ([email protected]) ORСID: 0000-0002-5750-7940 Scopus-Author ID: 57221085667 Olha KATRYCH PhD (Art), Professor, Academic Secretary of the Academic Council, Mykola Lysenko Lviv National Music Academy, 5 Ostapa Nyzhankivskoho Street, Lviv, Ukraine, postal code 79005 ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0002-2222-1993 Scopus-Author ID: 57221111370 ResearcherID: AAV-6310-2020 Jaroslaw CHACINSKI PhD (Humanities), Assistant Professor, Head of the Department of Music Art, Pomeranian Academy in Slupsk, 27 Partyzanów Street, Slupsk, Poland, postal code 76-200 ([email protected]) ORCID: 0000-0002-3825-8184 Мирослава НОВАКОВИЧ доктор мистецтвознавства, доцент, професор кафедри музичної медієвістики та україністики Львівської національної музичної академії імені Миколи Лисенка, вул. Остапа Нижанківського, 5, м. Львів, Україна, індекс 79005 ([email protected]) Ольга КАТРИЧ кандидат мистецтвознавства, професор, вчений секретар Львівської національної музичної академії імені Миколи Лисенка, вул. Остапа Нижанківського, 5, м. Львів, Україна, індекс 79005 ([email protected]) Ярослав ХАЦІНСЬКИЙ доктор філософії (PhD humanities), доцент,завідувач кафедри музичного мистецтва Поморської академії,вул. Партизанів 27, м. Слупськ, Польща, індекс 76-200 ([email protected]) Bibliographic Description of the Article: Novakovych, M., Katrych, O. & Chacinski, J. (2021). The role of music culture in the processes of the Ukrainian nation formation in Galicia (the second half of the XIXth – the beginning of the XXth century). -

Serhii Plokhy Mystifying the Nation: the History of the Rus' and Its

O d K i j O w a d O R z y m u Z dziejów stosunków Rzeczypospolitej ze Stolicą Apostolską i Ukrainą pod redakcją M. R. Drozdowskiego, W. Walczaka, K. Wiszowatej-Walczak Białystok 2012 Serhii Plokhy H arvard mystifying the Nation: The History of the Rus’ and its French models The History of the Rus’, a key text in the creation and dissemination of Ukrainian historical identity, began to circulate in St. Petersburg on the eve of the Decembrist Revolt of 1825. Among its admirers were some of the best-known Russian literary figures of the time, including Alexander Pushkin and Nikolai Gogol, as well as some of the empire’s most prominent rebels. These included Kondratii Ryleev, a poet who was hanged for his role in the Decembrist Revolt, and Taras Shevchenko, another poet generally recognized as the father of the modern Ukrainian nation, who was exiled to the Caspian steppes for his role in a clandestine Ukrainian organization. On the surface the History of the Rus’ is little more than a chronicle of the Ukrainian Cossacks. The narrative begins in the late Middle Ages and ends on the eve of the modern era. If one digs deeper, however, the manuscript is by no means what it appears to be.1 1 On the History of the Rus’, see: S. Kozak, U źródeł romantyzmu i nowożytnej myśli społecz- nej na Ukrainie, Wrocław 1978, pp. 70–135. For the latest literature on the subject, see Volodymyr Kravchenko, Poema vil’noho narodu (“Istoriia Rusiv” ta ïï mistse v ukraïns’kii istoriohrafiï), Kharkiv 1996; N. -

Visual Text and Musical Subtext: the Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): a 21St-Century Composer’S Journey in Silent Film Scoring

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 22 | 2021 Unheard Possibilities: Reappraising Classical Film Music Scoring and Analysis Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Century Composer’s Journey in Silent Film Scoring Robert Israel Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/38488 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.38488 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Robert Israel, “Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Century Composer’s Journey in Silent Film Scoring”, Miranda [Online], 22 | 2021, Online since 23 March 2021, connection on 26 April 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/38488 ; DOI: https:// doi.org/10.4000/miranda.38488 This text was automatically generated on 26 April 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Cen... 1 Visual Text and Musical Subtext: The Cossacks (George Hill, 1928): A 21st-Century Composer’s Journey in Silent Film Scoring Robert Israel 1 This piece aims to contextualize my contribution as ethnomusicologist, composer, orchestrator, arranger, conductor, choral director, producer, music contractor, and music editor for Turner Classic Movie’s presentation of MGM’s 1928 production of The Cossacks, directed by George Hill, with additional sequences directed by Clarence Brown. Working within a limited budget; doing research into the film’s historical era and the musical practices of the culture in which it takes place; finding source material, ethnic instruments, and musicians specializing in specific ethnic styles of music performance; and, other formidable challenges which I will outline here. -

Revue Des Études Slaves, LXXXV-3 | 2014 Taras Shevchenko: the Making of the National Poet 2

Revue des études slaves LXXXV-3 | 2014 Taras Ševčenko (1814-1861) Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet Taras Ševčenko: la fabrication d’un poète national George G. Grabowicz Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/res/398 DOI: 10.4000/res.398 ISSN: 2117-718X Publisher Institut d'études slaves Printed version Date of publication: 30 December 2014 Number of pages: 421-439 ISBN: 978-2-7204-0532-7 ISSN: 0080-2557 Electronic reference George G. Grabowicz, « Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet », Revue des études slaves [Online], LXXXV-3 | 2014, Online since 26 March 2018, connection on 14 December 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/res/398 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/res.398 This text was automatically generated on 14 December 2020. Revue des études slaves Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet 1 Taras Shevchenko: The Making of the National Poet Taras Ševčenko: la fabrication d’un poète national George G. Grabowicz 1 The bicentennial of Taras Shevchenko (1814-1861) coincided with a remarkable political and social upheaval—a revolution and a national renewal that as of this writing is still ongoing and still under attack in Ukraine.1 The core, and iconic, presence of Shevchenko in that process, and dramatically and symbolically on the Euromaidan itself, has often been noted and the revolutionary changes in which it was embedded will continue to draw the attention of political, sociological and cultural studies in the foreseeable future.2 If only through those manifest optics, Shevchenko was at the center of things in Ukraine—now, as often before. -

Dutch and Flemish Art in Russia

Dutch & Flemish art in Russia Dutch and Flemish art in Russia CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie) Amsterdam Editors: LIA GORTER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory GARY SCHWARTZ, CODART BERNARD VERMET, Foundation for Cultural Inventory Editorial organization: MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER, Foundation for Cultural Inventory WIETSKE DONKERSLOOT, CODART English-language editing: JENNIFER KILIAN KATHY KIST This publication proceeds from the CODART TWEE congress in Amsterdam, 14-16 March 1999, organized by CODART, the international council for curators of Dutch and Flemish art, in cooperation with the Foundation for Cultural Inventory (Stichting Cultuur Inventarisatie). The contents of this volume are available for quotation for appropriate purposes, with acknowledgment of author and source. © 2005 CODART & Foundation for Cultural Inventory Contents 7 Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN 10 Late 19th-century private collections in Moscow and their fate between 1918 and 1924 MARINA SENENKO 42 Prince Paul Viazemsky and his Gothic Hall XENIA EGOROVA 56 Dutch and Flemish old master drawings in the Hermitage: a brief history of the collection ALEXEI LARIONOV 82 The perception of Rembrandt and his work in Russia IRINA SOKOLOVA 112 Dutch and Flemish paintings in Russian provincial museums: history and highlights VADIM SADKOV 120 Russian collections of Dutch and Flemish art in art history in the west RUDI EKKART 128 Epilogue 129 Bibliography of Russian collection catalogues of Dutch and Flemish art MARIJCKE VAN DONGEN-MATHLENER & BERNARD VERMET Introduction EGBERT HAVERKAMP-BEGEMANN CODART brings together museum curators from different institutions with different experiences and different interests. The organisation aims to foster discussions and an exchange of information and ideas, so that professional colleagues have an opportunity to learn from each other, an opportunity they often lack. -

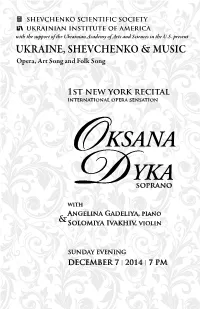

Concert Program

Oksana Dyka, soprano Angelina Gadeliya, piano • Solomiya Ivakhiv, violin I. Bellini Vincenzo Bellini Casta Diva (1801-1835) from Norma (1831) Program Mozart Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Porgi, amor, qualche ristoro (1756-1791) from The Marriage of Figaro (1786) Rossini Gioachino Rossini Selva opaca, Recitative and Aria (1792-1868) from Guglielmo Tell (William Tell, 1829) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya II. Shchetynsky Alexander Shchetynsky An Episode in the Life of the Poet, (b. 1960) an afterword to the opera Interrupted Letter (2014) World Premiere Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya III. From Poetry to Art Songs 1: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Shtoharenko Andriy Shtoharenko Yakby meni cherevyky (1902-1992) (If I had a pair of shoes, 1939) Silvestrov Valentin Silvestrov Proshchai svite (b. 1937) (Farewell world, from Quiet Songs, 1976) Shamo Ihor Shamo Zakuvala zozulen’ka (1925-1982) (A cuckoo in a verdant grove, 1958) Skoryk Myroslav Skoryk Zatsvila v dolyni (b. 1938) (A guelder-rose burst into bloom, 1962) Mussorgsky Modest Mussorgsky Hopak (1839-1881) from the opera Sorochynsky Fair (1880) Ms. Dyka • Ms. Gadeliya 2 Program — INTERMISSION — I V. Beethoven Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro vivace (1770-1827) from Sonata in G Major, Op. 30 (1801-1802) Vieuxtemps Henri Vieuxtemps Désespoir (1820-1881) from Romances sans paroles, Op. 7, No. 2 (c.1845) Ms. Ivakhiv • Ms. Gadeliya V. From Poetry to Art Songs 2: Settings of poems by Taras Shevchenko Lysenko Mykola Lysenko Oy, odna ya odna (1842-1912) (I’m alone, so alone, 1882) Rachmaninov Sergei Rachmaninov Poliubila ya na pechal’ svoyu, (1873-1943) Op. 8, No. 4 (I have given my love, 1893) Stetsenko Kyrylo Stetsenko Plavai, plavai, lebedon’ko (1882-1922) (Swim on, swim on, dear swan, 1903) Dankevych Konstantyn Dankevych Halia’s Aria (1905-1984) from the opera Nazar Stodolia (1960) VI. -

Romantic Poetry 1 Romantic Poetry

Romantic poetry 1 Romantic poetry Romanticism, a philosophical, literary, artistic and cultural era[1] which began in the mid/late-18th century[2] as a reaction against the prevailing Enlightenment ideals of the day (Romantics favored more natural, emotional and personal artistic themes),[3][4] also influenced poetry. Inevitably, the characterization of a broad range of contemporaneous poets and poetry under the single unifying name can be viewed more as an exercise in historical The Funeral of Shelley by Louis Edouard Fournier (1889); the group members, from left compartmentalization than an attempt to right, are Trelawny, Hunt and Byron to capture the essence of the actual ‘movement’.[citation needed] Poets such as William Wordsworth were actively engaged in trying to create a new kind of poetry that emphasized intuition over reason and the pastoral over the urban, often eschewing consciously poetic language in an effort to use more colloquial language. Wordsworth himself in the Preface to his and Coleridge's Lyrical Ballads defined good poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings,” though in the same sentence he goes on to clarify this statement by In Western cultural context romanticism substantially contibuted to the idea asserting that nonetheless any poem of of "how a real poet should look like". An idealized statue of a Czech poet value must still be composed by a man Karel Hynek Mácha (in Petřín Park, Prague) repesents him as a slim, tender “possessed of more than usual organic and perhaps unhealthy boy. However, anthropological examination proved sensibility [who has] also thought long that he was a man of a strong, robust and muscular body constitution. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1976, No.27

www.ukrweekly.com 1776 Happy it Birthday it America \m The Ukrainian Weekly Edition СВОБОДА SVOBODA УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОДЕННИК UKRAINIAN D A I LV VOL. LXXXIII No. 123 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JULY 4,1976 25 CENTS Thousands Help Celebrate Bicentennial- Centennial in Nation's Capital bylhorDlaboha George Washington WASHINGTON, D.C.—They came from all major Ukrainian communities east of Chicago with their American and Ukrainian flags, with placards calling for the release of Valentyn Moroz and with a great deal of pride in their past to the nation's capital, to pay homage to the Father of this Country, George Washing ton, and the Poet Laureat of Ukraine, Taras Shevchenko as a Bicentennial-Cen tennial tribute to the bi-national heritage of Ukrainian Americans. The parade here Saturday, June 26, and the two rallies at the Washington Monu ment and the Shevchenko Monument were the culminating events of a week long program celebrating the two anni versaries. Beginning last Monday, June 21, Ukrainian Americans, lead by the Ukrainian Bicentennial Committee of America the sponsoring organization, set Girls proudly carry banner telling its a Ukrainian parade. up several displays of Ukrainian culture and scholarship through out the capital TheFdtherOf city. White House Reception Hosts A fine and folk art exhibit at the Martin Luther King Library, a White House Our Country reception for Ukrainian youth and wo of the Ukrainian Bicentennial Committee 80 Ukrainian Youths, Women men's representatives, a scholarly sympo by Roma Sochan of America. sium, and finally today's manifestation, Mr. Lesawyer summarized the history which included Ukrainians from some 15 of Ukrainians in America, beginning with cities, all reflected their wanting to the arrival of Lavrentiy Bohoon in 1607 become a integral part of the American with Capt. -

Four Immortals Poets Garden at Arrow Park

FOUR IMMORTALS POETS GARDEN AT ARROW PARK CONTENTS FROM THE 1970 ORIGINAL COMMEMORATIVE BOOKLET REDESIGNED AS PART OF THE ARROW PARK HISTORICAL ARCHIVE – SEVENTIETH YEAR PROJECT — 1948-2018 ARROW PARK 1061 Orange Turnpike PO Box 465 Monroe, New York 10949 arrowparkny.com ORIGINALLY WRITTEN/PUBLISHED 1970 FOUR IMMORTALS Foreword This booklet is a collection of literary sketches of four world-known poets - Taras Shevchenko, Alexander Pushkin, Walt Whitman and Yanka Kupala. In introducing this booklet, we want to acquaint you with a short history of the monuments to the Four Immortals and Arrow Park where the monuments were erected. The park itself is situated in the beautiful hills of Upper New York State. One of its powerful attractions is a large lake for fishing, boating and swimming. Its vast wooded areas make for a beautiful resting place for the park's members and their friends. This naturally provided resort complex is complemented by specially built cottages for guests who spend their summers basking in the sun and enjoying the clean fresh air. Originally purchased by the progressive Russian American community, Arrow Park has presently become the center for other groups, including Ukrainian Americans, Polish Americans and many other nationality groups, in this manner adding an international touch to the whole project. During the summer months, Arrow Park hosts Ukrainian, Russian and Polish Days, at which the respective cultural groups (choirs, dancers and orchestras) present their programs and popularize the rich cultures of their nations for the benefit of warmly responding diverse audiences. Guided by the spirit of friendship and cultural relations with their brothers across the ocean, the shareholders of Arrow Park set up a special body, known as the Arrow Park Cultural Project Committee. -

Pavlo Zaitsev

PAVLO ZAITSEV Translated and edited by GEORGE S.N. LUCKYJ Taras Shevchenko A LI FE PAVLO ZAITSEV Translated and edited by George S.N. Luckyj Taras Shevchenko is undoubtedly Ukraine's greatest literary genius and national hero. His extraordinary life-story is recounted in this classic work by Pavlo Zaitsev. Born in 1814, the son of a poor serf, Shevchenko succeeded in winning his freedom and became an art student in St Petersburg. In 1847 he was arrested for writing revolutionary poetry, forced into the army, and exiled to deserted outposts of the Russian empire to undergo an incredible odys sey of misery for ten years. Zaitsev's re counting of Shevchenko's ordeal is a moving portrait of a man able not only to survive extreme suffering but to transform it into poetry that articulated the aspirations of his enslaved nation. To this day Ukrainians observe a national day of mourning each year on the anniversary of Shevchenko's death. Zaitsev's biography has long been recog nized by scholars as defmitive. Originally written and typeset in the 1930s, the manuscript was confiscated fro m Zaitsev by Soviet authori- ties when they annexed Galicia in 1939. The author still had proofs, however, which he revised and published in Munich in 1955. George luckyj's translation, the first in English, now offers this indispensable biography to a new audience. CEORCE S . N. LUCKYJ is Professor Emeritus of Slavic Studies, University of Toronto. He is the author of Literary Politics in tire Soviet Ukraine and Between Gogol and Shevclre11ko, and editor of Shm:henko and the Critics. -

Centre for Ukrainian Canadian Studies (CUCS)

University of Manitoba: Centre for Ukrainian Canadian Studies (CUCS) Back 15 March 2004 Discography of Shevchenko Songs Taras Shevchenko is extensively available on mainstream compact disc in compositions by Tchaikovsky, Mussorgsky, Rachmaninov, and Prokofiev. Since these composers were Russian, they worked in their own language for their own audiences. That means that these composers worked from Russian translations of Shevchenko and most of the works noted below are recorded in the Russian language. The exception is the Nelson Eddy recording of Hopak, which is sung in English. A word of warning to potential purchasers of these materials: Only one song on each disc has a Ukrainian connection. All other bands are typically Russian songs by these composers, not Ukrainian. Nevertheless, for researchers interested in obtaining examples of current recordings of Taras Shevchenko on mainstream labels, this bibliography should prove useful. Finally, it needs to be noted that the focus here is on mainstream recordings available online or through major audio shops such as A&B and HMV. The bibliography does not include specialty Ukrainian gift stores. ● Mussorgsky, M. (1866). On the Dnieper [Recorded by Vishnevskaya, G]. On Pictures at an Exhibition [CD]. 2GH 469-169: DG Panorama. 2000) ● Mussorgsky, M. (1866). On the Dnieper. [Same recording as above.]On Markevich/Vishnevskaya. 2000, BBCL 4053, BBC Legends. ● Mussorgsky, M. (1886). Gopak. On Boris Christoff: Recital [CD]. ERM 137: Ermitage. (1976) Also on EMI Great recordings of the Century, #67977, 2003. ● Mussorgsky, M. (1866). Hopak [Recorded by Linn Maxwell]. On Romances of the Russian Masters [CD]. TROY 072: Albany Records. (recorded 1992) ● Mussorgsky (1886).