World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Custodians of Culture and Biodiversity

Custodians of culture and biodiversity Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen for IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland The opinions expressed in this manual are those of the authors and do not nec - essarily represent those of IFAD. The designations employed and the presenta - tion of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IFAD concerning the legal status of any country, terri - tory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The designations “developed” and “developing” countries are in - tended for statistical convenience and do not necessarily express a judgement about the stage reached in the development process by a particular country or area. This manual contains draft material that has not been subject to formal re - view. It is circulated for review and to stimulate discussion and critical comment. The text has not been edited. On the cover, a detail from a Chinese painting from collections of Anita Kelles-Viitanen CUSTODIANS OF CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY Indigenous peoples take charge of their challenges and opportunities Anita Kelles-Viitanen For IFAD Funded by the IFAD Innovation Mainstreaming Initiative and the Government of Finland Table of Contents Executive summary 1 I Objective of the study 2 II Results with recommendations 2 1. Introduction 2 2. Poverty 3 3. Livelihoods 3 4. Global warming 4 5. Land 5 6. Biodiversity and natural resource management 6 7. Indigenous Culture 7 8. Gender 8 9. -

Guaraníes, Chanés Y Tapietes Del Norte Argentino. Construyendo El “Ñande Reko” Para El Futuro - 1A Ed Ilustrada

guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, Guaraníes, chanés y tapietes moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, del norte argentino. Construyendo huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, el ñande reko para el futuro sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, 2 selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, mapuche, kolla, wichí, pampa, moqoit/mocoví, omaguaca, ocloya, vilela, mbyá-guaraní, huarpe, mapuche-pehuenche, charrúa, chané, rankül- che, mapuche-tehuelche, atacama, comechingón, lule, sanavirón, chorote, tehuelche, diaguita cacano, selk’nam, diaguita calchaquí, qom/toba, günun-a-küna, chaná, guaycurú, chulupí/nivaclé, tonokoté, guaraní, quilmes, tapiete, -

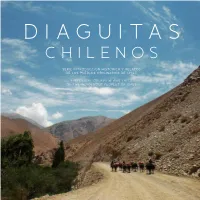

Diaguitas Chilenos

DIAGUITAS CHILENOS SERIE INTRODUCCIÓN HISTÓRICA Y RELATOS DE LOS PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS DE CHILE HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND TALES OF THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF CHILE DIAGUITAS CHILENOS |3 DIAGUITAS CHILENOS SERIE INTRODUCCIÓN HISTÓRICA Y RELATOS DE LOS PUEBLOS ORIGINARIOS DE CHILE HISTORICAL OVERVIEW AND TALES OF THE INDIGENOUS PEOPLES OF CHILE 4| Esta obra es un proyecto de la Fundación de Comunicaciones, Capacitación y Cultura del Agro, Fucoa, y cuenta con el aporte del Fondo Nacional para el Desarrollo de la Cultura y las Artes, Fondart, Línea Bicentenario Redacción, edición de textos y coordinación de contenido: Christine Gleisner, Sara Montt (Unidad de Cultura, Fucoa) Revisión de contenidos: Francisco Contardo Diseño: Caroline Carmona, Victoria Neriz, Silvia Suárez (Unidad de Diseño, Fucoa), Rodrigo Rojas Revisión y selección de relatos en archivos y bibliotecas: María Jesús Martínez-Conde Transcripción de entrevistas: Macarena Solari Traducción al inglés: Focus English Fotografía de Portada: Arrieros camino a la cordillera, Sara Mont Inscripción Registro de Propiedad Intelectual N° 239.029 ISBN: 978-956-7215-52-2 Marzo 2014, Santiago de Chile Imprenta Ograma DIAGUITAS CHILENOS |5 agradeciMientos Quisiéramos expresar nuestra más sincera gratitud al Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y las Artes, por haber financiado la investigación y publicación de este libro. Asimismo, damos las gracias a las personas que colaboraron en la realización del presente texto, en especial a: Ernesto Alcayaga, Emeteria Ardiles, Maximino Ardiles, Olinda Campillay, -

The Memorandum of Understanding Between Barrick Gold and Diaguita Communities of Chile

1 A Problematic Process: The Memorandum of Understanding between Barrick Gold and Diaguita Communities of Chile By Dr. Adrienne Wiebe, September 2015 For MiningWatch Canada and Observatorio Latinoamericano de Conflictos Ambientales (OLCA) “Canadians need to be aware of what Barrick is doing. The company is trying to make money at any cost, at the price of the environment and the life of communities. Canadians should not just believe what Barrick says. They should listen to what other voices, those from the local community, have to say.” – Raúl Garrote, Municipal Councillor, Alto del Carmen, Chile Introduction In May, 2014, Canadian mining company Barrick Gold announced that it had signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with 15 Diaguita communities in the area around the controversial Pascua Lama mine.i According to the company, the stated objective of the MOU between Diaguita Comunities and Associations with Barrick’s subsidiary Compañia Minera Nevada Spa in relation to Pascua Lama is to eXchange technical and environmental information about the project for which Barrick commited to provide financial and material resources to support its analysis. Barrick claimed that the MOU set a precedent in the world of international mining for community responsiveness and transparency. According to company officials, the agreements met and even exceeded the requirements of International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 169 and set a new standard for mining companies around the world in their relationships with local Indigenous communities.ii While this announcement sounded positive, the situation is much more compleX and problematic than that presented publically by Barrick Gold. The MOU raises questions regarding: 1) Indigenous identity, rights, and representation; 2) development and signing of the MOU, and 3) strategies used by mining companies to gain the so-called social licence from local populations. -

El-Arte-De-Ser-Diaguita.Pdf

MUSEO CHILENO DE ARTE PRECOLOMBINO 35 AÑOS 1 MUSEO CHILENO MINERA ESCONDIDA DE ARTE OPERADA POR PRECOLOMBINO BHP BILLITON 35 AÑOS PRESENTAN Organiza Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino Auspician Ilustre Municipalidad de Santiago Consejo Nacional de la Cultura y de las Artes Proyecto acogido a la Ley de Donaciones Culturales Colaboran Museo Arqueológico de La Serena – DIBAM Museo del Limarí – DIBAM Museo Nacional de Historia Natural – DIBAM Museo Histórico Nacional – DIBAM Museo de Historia Natural de Concepción – DIBAM Museo Andino, Fundación Claro Vial Instituto Arqueológico y Museo Prof. Mariano Gambier, San Juan, Argentina Gonzalo Domínguez y María Angélica de Domínguez Exposición Temporal Noviembre 2016 – Mayo 2017 EL ARTE DE SER DIAGUITA THE ART OF BEING Patrones geométricos representados en la alfarería Diaguita | Geometric patterns depicted in the Diaguita pottery. Gráca de la exposición El arte de ser Diaguita. DIAGUITA INTRODUCTION PRESENTACIÓN We are pleased to present the exhibition, The Art of Being Diaguita, but remains present today in our genetic and cultural heritage, La exhibición El Arte de ser Diaguita, que tenemos el gusto de Esta alianza de más de 15 años, ha dado nacimiento a muchas which seeks to delve into matters related to the identity of one of and most importantly in present-day indigenous peoples. presentar trata de ahondar en los temas de identidad de los pueblos, exhibiciones en Antofagasta, Iquique, Santiago y San Pedro de Chile’s indigenous peoples — the Diaguita, a pre-Columbian culture This partnership of more than 15 years has given rise to many en este caso, de los Diaguitas, una cultura precolombina que existía a Atacama. -

THE PEOPLES and LANGUAGES of CHILE by DONALDD

New Mexico Anthropologist Volume 5 | Issue 3 Article 2 9-1-1941 The eoplesP and Languages of Chile Donald Brand Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_anthropologist Recommended Citation Brand, Donald. "The eP oples and Languages of Chile." New Mexico Anthropologist 5, 3 (1941): 72-93. https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nm_anthropologist/vol5/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in New Mexico Anthropologist by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72 NEW MEXICO ANTHROPOLOGIST THE PEOPLES AND LANGUAGES OF CHILE By DONALDD. BRAND This article initiates a series in which the writer will attempt to summarize the scattered and commonly contradictory material on the present ethnic and linguistic constituency of a number of Latin Ameri- can countries. It represents some personal investigations in the field and an examination of much of the pertinent literature. Chile has been a sovereign state since the War of Independence 1810-26. This state was founded upon a nuclear area west of the Andean crest and essentially between 240 and 460 South Latitude. Through the War of the Pacific with Bolivia and Perui in 1879-1883 and peaceful agreements with Argentina, Chile acquired her present extention from Arica to Tierra del Fuego. These northern and south- ern acquisitions added little to her population but introduced numerous small ethnic and linguistic groups. Chile has taken national censuses in 1835, 1843, 1854, 1865, 1875, 1885, 1895, 1907, 1920, 1930, and the most recent one in November of 1940. -

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Argentina

Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Argentina Prepared for: The 28th Session of the United Nations Human Rights Council Universal Periodic Review March 2017 Cultural Survival is an international Indigenous rights organization with a global Indigenous leadership and consultative status with ECOSOC. Cultural Survival is located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and is registered as a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization in the United States. Cultural Survival monitors the protection of Indigenous peoples' rights in countries throughout the world and publishes its findings in its magazine, the Cultural Survival Quarterly; and on its website: www.cs.org Cultural Survival 2067 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02140 Tel: 1 (617) 441 5400 www.culturalsurvival.org [email protected] Observations on the State of Indigenous Human Rights in Argentina I. Executive Summary Historically Indigenous Peoples have struggled against Argentina’s state oppression, exclusion, and discrimination. Reporting on Indigenous Peoples in Argentina often fails to disaggregate data to demonstrate particular challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples. Available reports highlight the situation of Indigenous Peoples as one of serious marginalization. II. Background The total population of Argentina is around 43,886,748. 2.4% of the total population self-identify as Indigenous, belonging to more than 35 different Indigenous Peoples, the largest being the Mapuche (population: 205,009, 21.5% of the total), the Qom (126,967), and the Guaraní (105,907).i The rights of Indigenous Peoples were incorporated into Argentina’s Constitution in 1994, following the 1985 law on Indigenous Policy and Aboriginal Community Support,ii recognizing multi-ethnicity and acknowledging Indigenous customary law. -

State of the World's Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 (MRG)

State of the World’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 2016 Events of 2015 Focus on culture and heritage State of theWorld’s Minorities and Indigenous Peoples 20161 Events of 2015 Front cover: Cholitas, indigenous Bolivian Focus on culture and heritage women, dancing on the streets of La Paz as part of a fiesta celebrating Mother’s Day. REUTERS/ David Mercado. Inside front cover: Street theatre performance in the Dominican Republic. From 2013 to 2016 MRG ran a street theatre programme to challenge discrimination against Dominicans of Haitian Descent in the Acknowledgements Dominican Republic. MUDHA. Minority Rights Group International (MRG) Inside back cover: Maasai community members in gratefully acknowledges the support of all Kenya. MRG. organizations and individuals who gave financial and other assistance to this publication, including the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. © Minority Rights Group International, July 2016. All rights reserved. Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non-commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for Support our work commercial purposes without the prior express Donate at www.minorityrights.org/donate permission of the copyright holders. MRG relies on the generous support of institutions and individuals to help us secure the rights of For further information please contact MRG. A CIP minorities and indigenous peoples around the catalogue record of this publication is available from world. All donations received contribute directly to the British Library. our projects with minorities and indigenous peoples. ISBN 978-1-907919-80-0 Subscribe to our publications at State of www.minorityrights.org/publications Published: July 2016 Another valuable way to support us is to subscribe Lead reviewer: Carl Soderbergh to our publications, which offer a compelling Production: Jasmin Qureshi analysis of minority and indigenous issues and theWorld’s Copy editing: Sophie Richmond original research. -

Cultura Y Alimentación Indígena En Chile

CULTURA Y ALIMENTACIÓN INDÍGENA EN CHILE 1 2 CULTURA Y ALIMENTACIÓN INDÍGENA EN CHILE - Presentacion La comida ha estado en el centro de la vida familiar y ha organizado el trabajo de las comunidades a lo largo de la historia de la humanidad. Todos los pueblos han atesorado su repertorio gastronómico como una forma de identificarse en el mundo, de provocar placer y de resolver necesidades. Un viejo proverbio recomendaba que toda diferencia de opiniones se resolviera siempre después de un ban- quete. “Dios nos libre de un juez con hambre”, advertía otro antiguo dicho popular. La cocina congrega y humaniza, la buena alimentación convoca la paz y garantiza la justicia. Fue gracias a los intercambios de semillas, animales y prácticas culinarias que muchas sociedades han podido luchar contra el flagelo del hambre. Cuando miramos al pasado, es difícil imaginar la supervivencia de la humanidad sin el enorme aporte de alimentos originarios en el continente ame- ricano, región que tiene como Centro de Origen las más diversas especies hoy consideradas básicas para la alimentación humana. El placer de los sabores desconocidos ha obsesionado a infinidad de viajeros y cronistas antiguos, que sabían que nunca se termina de conocer una región si no se experimentan sus aromas, si no se ejerce la curiosidad por sus comidas y sus métodos culinarios. A lo largo de Chile, el mar, los valles verdes y la montaña han nutrido a la cocina indígena con platos diversos y una muy vasta tradición culinaria, de la que queremos dar una pequeña muestra en este libro. Se trata de recetas breves que permiten preparar las comidas que durante toda su historia han preparado las culturas indígenas en las distin- tas regiones del país. -

Infinity of Nations: Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian

Infinity of Nations: Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian Exhibition Checklist: Kuna Kantule hat Darién Province, Panama Headdresses ca. 1924 Palm leaves, macaw and harpy feathers, reed, cotton Assiniboine antelope-horn headdress cord Saskatchewan, Canada 12/9169 ca. 1850 Antelope horn, deer hide, porcupine quills, feathers, Mapuche head ornament horsehair red wool, brass bells, glass beads Trumpulo Chico, Chile 10/8302 ca. 1975 Wool, ostrich feathers 25/9039 Miccosukee Seminole turban Florida Haida frontlet headdress ca. 1930 Prince of Wales Islands, British Columbia Cotton, silver, ostrich feathers, hide ca. 1850 20/4363 Ermine, wood, haliotis shell, sea lion whiskers, wool, cotton Yup'ik hunting hat 10/4581 Yukon River, Alaska ca. 1870 Wood, ivory, baleen, iron alloy, cordage Patagonia 10/6921 Mapuche machi’s rewe pole Tiwanaku four-cornered hat Collico, Chile Chimbote, Peru ca. 1920 A.D. 600–1000 Wood Alpaca wool, dye 17/5773 22/3722 Diaguita vessel Mebêngôkre krokrokti (feather headdress or cape) Temuco, Chile Brazil A.D. 1500s ca. 1990 Clay, paint Macaw feathers, heron feathers, cotton cordage 17/7543 25/4893 Mapuche breast ornament Yoeme deer dance headdress Chile Sonora, Mexico ca. 1925 ca. 1910 Silver Deer hide, glass eyes, antlers 23/147 11/2382 Diaguita bowl Elqui Province, Chile Karuk headdress A.D. 950–1450 California Clay, paint ca. 1910 17/5128 Deer hide, woodpecker and bluejay feathers 20/9651 1 Infinity of Nations: Art and History in the Collections of the National Museum of the American Indian Early Mapuche whistle Enxet pipe Quitratúe, Chile Paraguay A.D. -

The Peopling of South America and the Trans-Andean Gene Flow of the First Settlers

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 6, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research The peopling of South America and the trans-Andean gene flow of the first settlers Alberto Gómez-Carballa,1,2,3,8 Jacobo Pardo-Seco,1,2,3 Stefania Brandini,4 Alessandro Achilli,4 Ugo A. Perego,4 Michael D. Coble,5 Toni M. Diegoli,6,7 Vanesa Álvarez-Iglesias,1,2 Federico Martinón-Torres,3 Anna Olivieri,4 Antonio Torroni,4 and Antonio Salas1,2,8 1Unidade de Xenética, Departamento de Anatomía Patolóxica e Ciencias Forenses, Instituto de Ciencias Forenses, Facultade de Medicina, Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 15782 Galicia, Spain; 2GenPoB Research Group, Instituto de Investigaciones Sanitarias (IDIS), Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela, 15706 Galicia, Spain; 3Grupo de Investigación en Genética, Vacunas, Infecciones y Pediatría (GENVIP), Hospital Clínico Universitario and Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, 15706 Galicia, Spain; 4Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie, Università di Pavia, 27110 Pavia, Italy; 5Applied Genetics Group, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, Maryland 20899, USA; 6Office of the Chief Scientist, Defense Forensic Science Center, Ft. Gillem, Georgia 30297, USA; 7Analytical Services, Incorporated, Arlington, Virginia 22201, USA Genetic and archaeological data indicate that the initial Paleoindian settlers of South America followed two entry routes separated by the Andes and the Amazon rainforest. The interactions between these paths and their impact on the peopling of South America remain unclear. Analysis of genetic variation in the Peruvian Andes and regions located south of the Amazon River might provide clues on this issue. We analyzed mitochondrial DNA variation at different Andean locations and >360,000 autosomal SNPs from 28 Native American ethnic groups to evaluate different trans-Andean demographic scenarios. -

Indigenous Movements, Citizenship and Poverty in Argentina

‘We Have Always Lived Here’: Indigenous Movements, Citizenship and Poverty in Argentina 1 Matthias vom Hau Guillermo Wilde2 1 The University of Manchester 2Universidad de San Martin, Buenos Aires [email protected] [email protected] July 2009 BWPI Working Paper 99 Brooks World Poverty Institute ISBN : 978-1-906518-98-1 Creating and sharing knowledge to help end poverty www.manchester.ac.uk/bwpi Abstract This paper explores the new politics of difference in Argentina since the 1994 constitutional reform, and its ramifications for citizenship and indigenous wellbeing. Through a comparison of land struggles among the Mbya Guaraní in Misiones and the Diaguita Calchaquí in Tucumán it is shown that new collective rights only gained traction once indigenous social movements employed the language of ‘differentiated rights’ and pushed for the implementation of multicultural legislation. At the same time, local indigenous communities continue to face adverse socioeconomic incorporation, and the new legal frameworks focus on land rights, thereby foreclosing the establishment of indigenous control over territory. The current politics of recognition in Argentina thus plays a crucial role in deepening cultural and political citizenship, while its impacts remain limited for addressing broader issues of social justice. Keywords: Social movements, Citizenship, Multiculturalism, Poverty, Development, Latin America Matthias vom Hau is Lewis-Gluckman Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Brooks World Poverty Institute, The University of Manchester. Guillermo Wilde is a Researcher at IDAES (Instituto de Altos Estudios Sociales), Universidad de San Martín, Buenos Aires. Acknowledgements The order of authorship is alphabetical. We would like to thank the Chronic Poverty Research Centre (CPRC) for funding this research, and Sam Hickey, Tony Bebbington and Alejandro Grimson for their helpful and detailed comments on the argument developed here.