Chapter 1 the Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Meanings of Boundaries: Contested Landscapes of Resource

The Meanings of Boundaries: Contested Landscapes of Resource Use in Malawi Peter A. Walker Department of Geography, University of Oregon Eugene, OR 97403-1251 [email protected] Fax: (541) 346-2067 Pauline E. Peters Harvard Institute for International Development, Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Fax: (617) 495-0527 Stream: Multiple Commons Discipline: Geography/Anthropology This paper examines the changing meanings of boundaries that demarcate community, private, and public land in Malawi and their roles in shaping resource use. Boundaries have long been a central concept in many social science disciplines, and recently considerable attention has been given to the ways that boundaries—whether physical or socio-cultural—are socially constructed and contested. In some cases landscapes are said to reflect multiple overlapping or multi-layered boundaries asserted by competing social groups. In other cases boundaries are said to be blurred, or even erased, through social contests and competing discourses. The authors of this paper, one a geographer, one an anthropologist, suggest that such choices in analytical language and metaphors tend to obscure certain key social dynamics in which boundaries play a central role. Specifically, the paper argues that in the two case studies presented from southern and central Malawi, social contests focus not on competing (‘overlapping’, or ‘multi-layered’) sets of spatially-defined boundaries but over the meanings of de jure boundaries that demarcate community, private, and state land. In asserting rights to use resources on private and state land, villagers do not seek to shift or eliminate the boundaries marking community and private or state land or to assert alternative sets of spatial boundaries. -

Property Rights, Land and Territory in the European Overseas Empires

Property Rights, Land and Territory in the European Overseas Empires Direitos de Propriedade, Terra e Território nos Impérios Ultramarinos Europeus Edited by José Vicente Serrão Bárbara Direito, Eugénia Rodrigues and Susana Münch Miranda © 2014 CEHC-IUL and the authors. All rights reserved. Title: Property Rights, Land and Territory in the European Overseas Empires. Edited by: José Vicente Serrão, Bárbara Direito, Eugénia Rodrigues, Susana Münch Miranda. Editorial Assistant: Graça Almeida Borges. Year of Publication: 2014. Online Publication Date: April 2015. Published by: CEHC, ISCTE-IUL. Avenida das Forças Armadas, 1649-026 Lisboa, Portugal. Tel.: +351 217903000. E-mail: [email protected]. Type: digital edition (e-book). ISBN: 978-989-98499-4-5 DOI: 10.15847/cehc.prlteoe.945X000 Cover image: “The home of a ‘Labrador’ in Brazil”, by Frans Post, c. 1650-1655 (Louvre Museum). This book incorporates the activities of the FCT-funded Research Project (PTDC/HIS-HIS/113654/2009) “Lands Over Seas: Property Rights in the Early Modern Portuguese Empire”. Contents | Índice Introduction Property, land and territory in the making of overseas empires 7 José Vicente Serrão Part I Organisation and perceptions of territory Organização e representação do território 1. Ownership and indigenous territories in New France (1603-1760) 21 Michel Morin 2. Brazilian landscape perception through literary sources (16th-18th centuries) 31 Ana Duarte Rodrigues 3. Apropriação econômica da natureza em uma fronteira do império atlântico 43 português: o Rio de Janeiro (século XVII) Maria Sarita Mota 4. A manutenção do território na América portuguesa frente à invasão espanhola da 55 ilha de Santa Catarina em 1777 Jeferson Mendes 5. -

A Right to Land?

Aadfadffa rightdfdadfadf to land? Population density and land rights in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, 1923-2013 Jenny de Nobel UNIVERSITEIT LEIDEN July 2016 A right to land? Population density and land rights in Malawi, Zambia and Zimbabwe, 1923-2013 A MASTER THESIS by Jenny de Nobel s1283545 Supervised by: prof. dr. Jan-Bart Gewald Second reader: dr. Marleen Dekker ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to prof. Bas van Bavel for introducing me to the academic study of long-term economic patterns. Discerning the drivers of change and essentially questioning how the foundations of societies lead to certain paths of development has inspired much of my work as a student of history. Prof. Nick Vink and prof. Ewout Frankema helped me channel this interest to an area that has been noticeably absent in the literature on questions of global development or the 'Great Divergence': Africa. I can only hope that this study can help fill that hiatus. My gratitude to dr. Cátia Antunes and prof. Robert Ross for sharing their thoughts with me and guiding me through the myriad of ideas that were once the momentum of this thesis. Many thanks to prof. Jan-Bart Gewald for his guidance, support and open-minded approach to my ideas, and dr. Dekker for her comments. Lastly, thanks to my friends and family who kept me going throughout this journey. Your support was invaluable, and this work would not be there without it. Two people, especially, made this possible, and how lucky I am that they are my parents: thank you for your endless faith. -

The Commons in the Age of Globalisation Conference

THE COMMONS IN THE AGE OF GLOBALISATION CONFERENCE Transactive Land Tenure System In The Face Of Globalization In Malawi Paper by: Dr. Edward J.W. CHIKHWENDA, BSc(Hons), MSc, MSIM, LS(Mw) University of Malawi Polytechnic P/Bag 303 Chichiri, Blantyre 3 Malawi Abstract Globalisation is a major challenge to the sustainability of both the social and economic situation of developing countries like Malawi. Since the introduction of western influence in the 1870s, Malawi has experienced social, cultural and economic transformation. The transformation has been both revolutionary and evolutionary. After ten decades of British influence, Malawi achieved economic progress in the 1970s. However, in the 1980s Malawi witnessed a significant depletion in the savings capability in the face of rising population, decline in economic growth and foreign exchange constraints(UN, 1990). This decline has continued up to the present day despite the globalization of the world economy. In fact, globalization has exacerbated economic growth and development in Malawi. It is the aim of this paper to identify the policies that need to be applied in Malawi in order to arrest the further deterioration in socio-cultural and economic situation. The fact that almost 80 percent of population in Malawi is rural, implies that land issues are paramount in inducing accelerated sustainable growth and development. The paper will focus on policies that encourage shared responsibility and strengthening of partnerships at all levels of the community. In this analysis, the importance and role of the customary land tenure concepts, practices and their associated hierarchies will be unearthed in order to provide unified concepts that are in tune with the western concepts of land and property stewardship. -

Brian Morris Palgrave Studies in World Environmental History

Palgrave Studies in World Environmental History AN ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY OF SOUTHERN MALAWI Land and People of the Shire Highlands Brian Morris Palgrave Studies in World Environmental History Series Editors Vinita Damodaran Department of History University of Sussex Brighton, United Kingdom Rohan D’Souza Graduate School of Asian and African Area Studies Kyoto University Kyoto, Japan Sujit Sivasundaram University of Cambridge Cambridge, United Kingdom James John Beattie Department of History University of Waikato Hamilton, New Zealand Aim of the Series The widespread perception of a global environmental crisis has stimulated the burgeoning interest in environmental studies. This has encouraged a wide range of scholars, including historians, to place the environment at the heart of their analytical and conceptual explorations. As a result, the under- standing of the history of human interactions with all parts of the culti- vated and non-cultivated surface of the earth and with living organisms and other physical phenomena is increasingly seen as an essential aspect both of historical scholarship and in adjacent fields, such as the history of science, anthropology, geography and sociology. Environmental history can be of considerable assistance in efforts to comprehend the traumatic environmen- tal difficulties facing us today, while making us reconsider the bounds of possibility open to humans over time and space in their interaction with different environments. This new series explores these interactions in stud- ies that together touch on all parts of the globe and all manner of environ- ments including the built environment. Books in the series will come from a wide range of fields of scholarship, from the sciences, social sciences and humanities. -

Mining Rights in Zambia

MINING RIGHTS IN ZAMBIA MINING RIGHTS IN ZAMBIA Muna Ndulo LLB (Zambia) LLM (Harvard) D. Phil (Oxon) Advocate of the High Court for Zambia, Professor of Law, University of Zambia. Kenneth Kaunda Foundation Muna Ndulo, 1987 First Published 1987 by Kenneth Kaunda Foundation (Publishing and Printing Division) P. O. Box 32664, Lusaka, Zambia ISBN 9982-01-001-8 Printed in Zimbabwe by Print Holdings Dedicated to my parents Temba and Julia: They started it all. PREFACE A legal framework is required for most human endeavours, whether it be to apply justice or to establish codes of public conduct or to provide facilities for the conduct of social or economic life by regulating and thus enabling such activities to be carried out in an orderly manner. The number of these activities have proliferated considerably mostly as a result of the extraordinary industrial and social development of the world. Hence, like in all other activities legislation is required to establish rules and regulations to control mining activities. This book is an attempt to provide a detailed study of such a legal framework within which the orderly development and operations relating to the activities of mineral exploitation in Zambia are carried out. The term mining law here is used to mean those enactments which in various ways regulate the acquisition and tenure of mining rights and mining grounds, and the practice of mining-right holders. It relates primarily to the disposition of mining rights and the specific imposts that relate to the exploitation of mineral deposits. The main aspects of mining law cover such things as definition of minerals, ownership of resources, law relating to the right to mine, conditions of governing the issue and holding of mining rights, and the relationship between mineral-and surface-right holders. -

A History of Archives in Zambia, 1890-1991

A HISTORY OF ARCHIVES IN ZAMBIA, 1890-1991 MIYANDA SIMABWACHI THIS THESIS HAS BEEN SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FOR THE CENTRE FOR AFRICA STUDIES, AT THE UNIVERSITY OF THE FREE STATE SUPERVISOR: DR. LINDIE KOORTS CO-SUPERVISORS: PROF. JACKIE DU TOIT DR. CHRIS HOLDRIDGE FEBRUARY 2019 Declaration I hereby declare that this thesis, submitted in accordance with the requirements for the award of the doctoral degree in Africa Studies in the Faculty of Humanities, for the Centre for Africa Studies at the University of the Free State is my original work and has not been previously submitted to another university for a degree. I hereby authorise copyright of this product to the University of the Free State. Signed: ________________ Date: _________________ Miyanda Simabwachi Dedication I dedicate this work to my loving mother, Rosemary Zama Simabwachi, for her unwavering support in parenting my daughters (Natasha and Mapalo) throughout the duration of my study. TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................................. i OPSOMMING .......................................................................................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... iii LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................ -

Law, Social Justice & Global Development

Law, Social Justice & Global Development (An Electronic Law Journal) Customary Land Tenure Reform and Development: A Critique of Customary Land Tenure Reform under Malawi’s National Land Policy Chikosa Mozesi Silungwe PhD Candidate School of Law University of Warwick [email protected] This is a Refereed Article published on: 23 April 2009 Citation: Silungwe, C. ‘Customary Land Tenure Reform and Development: A Critique of Customary Land Tenure Reform under Malawi’s National Land Policy’, 2009 (1) Law, Social Justice & Global Development Journal (LGD). http://www.go.warwick.ac.uk/elj/lgd/2009_1/silungwe Silungwe, C. 1 Customary Land Tenure Reform and Development Abstract Development, as a post–Second World War phenomenon, has witnessed the dominance of the market at the close of the twentieth century. In relation to agrarian reform, neo–liberal land reform models laud individual title as a catalyst for economic growth. Customary land tenure has been adjudged anathema to development as it is supposedly economically inefficient. The economy efficiency argument is not new. In Malawi, colonial and post–colonial land law and policy has favoured individual title in pursuit of a ‘capitalist’ economy. In 2002, Malawi adopted a National Land Policy. Despite the claims of a fair redistribution of land to the ‘poor’, the policy adopts a neo–liberal approach to customary land tenure reform, inter alia, to promote a formal land market. The implications of the neo–liberal framework for the ‘poor’ is that it will benefit the ‘non–poor’; it leads to the integration of customary land into the global economy; it perpetuates landlessness on the part of the ‘poor’ who might not withstand the vagaries of a formal land market. -

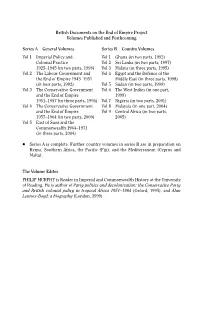

Central Africa Editor PHILIP MURPHY Part I CLOSER

00-Central Africa-Blurb-cpp 7/10/05 6:53 AM Page 1 British Documents on the End of Empire Project Volumes Published and Forthcoming Series A General Volumes Series B Country Volumes Vol 1 Imperial Policy and Vol 1 Ghana (in two parts, 1992) Colonial Practice Vol 2 Sri Lanka (in two parts, 1997) 1925–1945 (in two parts, 1996) Vol 3 Malaya (in three parts, 1995) Vol 2 The Labour Government and Vol 4 Egypt and the Defence of the the End of Empire 1945–1951 Middle East (in three parts, 1998) (in four parts, 1992) Vol 5 Sudan (in two parts, 1998) Vol 3 The Conservative Government Vol 6 The West Indies (in one part, and the End of Empire 1999) 1951–1957 (in three parts, 1994) Vol 7 Nigeria (in two parts, 2001) Vol 4 The Conservative Government Vol 8 Malaysia (in one part, 2004) and the End of Empire Vol 9 Central Africa (in two parts, 1957–1964 (in two parts, 2000) 2005) Vol 5 East of Suez and the Commonwealth 1964–1971 (in three parts, 2004) ● Series A is complete. Further country volumes in series B are in preparation on Kenya, Southern Africa, the Pacific (Fiji), and the Mediterranean (Cyprus and Malta). The Volume Editor PHILIP MURPHY is Reader in Imperial and Commonwealth History at the University of Reading. He is author of Party politics and decolonization: the Conservative Party and British colonial policy in tropical Africa 1951–1964 (Oxford, 1995), and Alan Lennox-Boyd: a biography (London, 1999) 01A-Map of Africa 7/10/05 6:56 AM Page 2 GABON R. -

Population Dynamics of Malawi: a Re-Examination of the Existing Demographic Data

Population Dynamics of Malawi: A Re-examination of the Existing Demographic Data MARTIN ENOCK PALAMULENI a thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy to the Faculty of Economics, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), University of London. December 1991 UMI Number: U056058 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U056058 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 or 'v political w| . JJ 'T0ttc\ 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the dynamics of population growth in Malawi with particular reference to the two decades immediately following independence. Due to insufficient data little is known about the demography of Malawi. This dissertation is therefore an attempt to remedy the situation and provide additional questions for future inquiries. Reliance has been on published demographic data obtained from the national censuses and demographic surveys. Reference has also been made to studies by independent researchers and other social and economic indicators obtained from various government publications. The inquiry begins by reviewing previous attempts to examine the population of Malawi. -

Imagined Communities: the British Planter in Nyasaland, 1890 - 1940

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 Imagined Communities: The British Planter in Nyasaland, 1890 - 1940 Benjamin Marnell Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Africana Studies Commons “Imagined Communities: The British Planter in Nyasaland, 1890-1940” Benjamin Marnell Thesis submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in History Joseph M. Hodge, PhD, Chair James Siekmeier, PhD Jennifer Thornton, PhD Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2021 Keywords: Malawi, Tea, British Empire, Colonialism, British World, Identity Copyright 2021 Benjamin Marnell Abstract The planters’ Legacy in Nyasaland “Imagined Communities: The British Planter in Nyasaland, 1890-1940” Benjamin Marnell This thesis examines concepts of British settler identity and how it developed across trans-national bounds. Between the 19th and 20th centuries, the rise of industrialization and developments in transportation, mass communication and print media fueled a new wave of settler movements from Britain. As settlers spread to different continents, their identity as Britons was challenged in new ways. From this, a unique subgroup of settlers developed, known as planters. In this thesis, I examine the planter community that developed in the small South Central African country of Nyasaland, now Malawi. By examining Nyasaland’s settler community as a case study, I show how the planters drew inspiration from other planting communities across the empire to develop an identity that strengthened their hold over the region. Though the planters failed in their attempt to create their imagined community, this thesis will show how they attempted to contribute to the trans-national planting class and how that shaped their perceived dominance over the African population. -

LAW and AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT in ZAMBIA By

LAW AND AGRICULTURAL DEVELOPMENT IN ZAMBIA by ANTHONY CYRIL MULIMBWA A thesis submitted to the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Law. Date: June, 1987 ProQuest Number: 11010493 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010493 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 ABSTRACT Agriculture occupies a very important place in the Zambian economy as a source of foreign exchange and as a source of food. Whatever the explanations that have been offered for low productivity - droughts, excessive rains etc., the legal framework for agriculture has been a relevant factor even though it has received the least attention from lawyers and economists alike. Law and development studies have only assumed importance in the last twenty years, that is, since the attainment of independence of many African countries. This thesis seeks to add to the growing literature on the effect of law on the agricultural development of Zambia. It is divided into five substantive chapters and a conclusion.