Bill Mckibben Is an Activist and Architect of the Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Run on the Rock

House of Commons Treasury Committee The run on the Rock Fifth Report of Session 2007–08 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 January 2008 HC 56–II [Incorporating HC 999 i–iv, Session 2006-07] Published on 1 February 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £25.50 The Treasury Committee The Treasury Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of HM Treasury, HM Revenue & Customs and associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon John McFall MP (Labour, West Dunbartonshire) (Chairman) Nick Ainger MP (Labour, Carmarthen West & South Pembrokeshire) Mr Graham Brady MP (Conservative, Altrincham and Sale West) Mr Colin Breed MP (Liberal Democrat, South East Cornwall) Jim Cousins MP (Labour, Newcastle upon Tyne Central) Mr Philip Dunne MP (Conservative, Ludlow) Mr Michael Fallon MP (Conservative, Sevenoaks) (Chairman, Sub-Committee) Ms Sally Keeble MP (Labour, Northampton North) Mr Andrew Love MP (Labour, Edmonton) Mr George Mudie MP (Labour, Leeds East) Mr Siôn Simon MP, (Labour, Birmingham, Erdington) John Thurso MP (Liberal Democrat, Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross) Mr Mark Todd MP (Labour, South Derbyshire) Peter Viggers MP (Conservative, Gosport). Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

$1.2 Million Conflict of Interest Plagues Climate Change Denial Research

$1.2 Million Conflict of Interest Plagues Climate Change Denial Research... http://natmonitor.com/2015/02/22/1-2-million-conflict-of-interest-plague... $1.2 Million Conflict of Interest Plagues Climate Change Denial Research By James Paladino, National Monitor | February 22, 2015 A recently uncovered document shows that Wei-Hok Soon, a well-known aerospace engineer, was granted over $1.2 million from fossil-fuel companies for climate research and failed to disclose a conflict of interest in his peer-reviewed publications. In Washington, climate change deniers are fighting a fierce battle to stave off energy policy reform. The latest casualty of this war of ideas is Wei-Hock Soon, a part-time employee of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Resilient to the scientific consensus that human carbon emissions are fueling gradual warming, the aerospace engineer has served as a beacon for conservative legislators. A recently uncovered document shows that Soon was granted over $1.2 million from fossil-fuel companies and failed to disclose a conflict of interest in his peer-reviewed publications. Since the Smithsonian is part of the federal government, former Greenpeace member Kert Davies legally obtained the Soon’s grant agreements through the Freedom of Information Act. Contributors include the American Petroleum Institute, the Koch brothers, Exxon Mobil and Southern Company. Several scientific papers and a congressional testimonial were termed as “deliverables,” reports The New York Times. “These proposals and contracts show debatable interventions in science literally on behalf of the Southern Company and the Kochs,” said Davies. “What it shows is the continuation of a long-term campaign by specific fossil-fuel companies and interests to undermine the scientific consensus on climate change.” These recent revelations have drawn fire from members of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center and NASA, among others. -

Climate Change Scepticism: a Transnational Ecocritical Analysis

Garrard, Greg. "Climate Scepticism in the UK." Climate Change Scepticism: A Transnational Ecocritical Analysis. By Greg GarrardAxel GoodbodyGeorge HandleyStephanie Posthumus. London,: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 41–90. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 26 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350057050.ch-002>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 26 September 2021, 23:43 UTC. Copyright © Greg Garrard, George Handley, Axel Goodbody and Stephanie Posthumus 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 2 Climate Scepticism in the UK Greg Garrard Before embarking on a detailed analysis of sceptical British texts, I will provide some historical and scholarly context. There have been many studies of anti- environmentalism in the United States (Helvarg; Brick; Ehrlich and Ehrlich; Switzer) and one on the global ‘backlash’ (Rowell), but none focuses exclusively on the UK. The sole treatment of anti-environmentalism within ecocriticism comes from the United States (Buell), just like the various exposés of climate scepticism discussed in the Introduction. As this chapter will show, British climate scepticism is possessed of a prehistory and some distinctive local features that reward closer inspection. Nevertheless, the Anglo-American axis of organized anti-environmentalism is obvious: British climate sceptics such as Christopher Monckton, James Delingpole and Nigel Lawson are darlings of the American conservative think tanks (CTTs) that promulgate sceptical perspectives, while Martin Durkin’s The Great Global Warming Swindle (2007), a British documentary shown on Channel 4, includes interviews with Richard Lindzen, Patrick Michaels and Fred Singer, all prominent American sceptics. -

Matt Ridley – a Lukewarmer's Ten Tests

A LUKEWARMER’S TEN TESTS What It Would Take To Persuade Me That Current Climate Policy Makes Sense Matt Ridley The Global Warming Policy Foundation GWPF Notes GWPF REPORTS Views expressed in the publications of the Global Warming Policy Foundation are those of the authors, not those of the GWPF, its Trustees, its Academic Advisory Council members or its Directors. THE GLOBAL WARMING POLICY FOUNDATION Director Dr Benny Peiser Assistant Director Philipp Mueller BOARD OF TRUSTEES Lord Lawson (Chairman) Baroness Nicholson Lord Donoughue Lord Turnbull Lord Fellowes Sir James Spooner Rt Rev Peter Forster Bishop of Chester Sir Martin Jacomb ACADEMIC ADVISORY COUNCIL Professor David Henderson (Chairman) Professor Richard Lindzen Adrian Berry (Viscount Camrose) Professor Ross McKitrick Sir Samuel Brittan Professor Robert Mendelsohn Sir Ian Byatt Professor Sir Alan Peacock Professor Robert Carter Professor Ian Plimer Professor Vincent Courtillot Professor Paul Reiter Professor Freeman Dyson Dr Matt Ridley Christian Gerondeau Sir Alan Rudge Dr Indur Goklany Professor Philip Stott Professor William Happer Professor Richard Tol Professor Terence Kealey Dr David Whitehouse Professor Anthony Kelly Professor Deepak Lal A Lukewarmer’s Ten Tests A Lukewarmer’s Ten Tests What It Would Take To Persuade Me That Current Climate Policy Makes Sense Dr Matt Ridley Matt Ridley has been a scientist, journalist and businessman. With BA and DPhil degrees from Oxford University, he worked for the Economist for nine years as science editor, Washington correspondent and American editor, before becoming a self-employed writer and businessman. He is the author of several books, which have sold over 900,000 copies, been translated into 30 languages, been short-listed for nine major literary prizes and won several awards. -

THE CLIMATE WARS and the Damage to Science Matt Ridley

THE CLIMATE WARS and the damage to science Matt Ridley The Global Warming Policy Foundation GWPF Essay 3 GWPF REPORTS Views expressed in the publications of the Global Warming Policy Foundation are those of the authors, not those of the GWPF, its Academic Advisory Coun- cil members or its directors THE GLOBAL WARMING POLICY FOUNDATION Director Benny Peiser BOARD OF TRUSTEES Lord Lawson (Chairman) Peter Lilley MP Lord Donoughue Charles Moore Lord Fellowes Baroness Nicholson Rt Revd Dr Peter Forster, Bishop of Chester Graham Stringer MP Sir Martin Jacomb Lord Turnbull ACADEMIC ADVISORY COUNCIL Professor Ross McKitrick(Chairman) Professor Deepak Lal Adrian Berry Professor Richard Lindzen Sir Samuel Brittan Professor Robert Mendelsohn Sir Ian Byatt Professor Ian Plimer Professor Robert Carter Professor Paul Reiter Professor Vincent Courtillot Dr Matt Ridley Professor Freeman Dyson Sir Alan Rudge Professor Christopher Essex Professor Nir Shaviv Christian Gerondeau Professor Philip Stott Dr Indur Goklany Professor Henrik Svensmark Professor William Happer Professor Richard Tol Professor David Henderson Professor Fritz Vahrenholt Professor Terence Kealey Dr David Whitehouse CREDITS Cover image David King under CC licence https://www.flickr.com/photos/bootbearwdc/515399703 THE CLIMATE WARS and the damage to science Matt Ridley c Copyright 2015 The Global Warming Policy Foundation Contents About the author vi 1 Introduction 1 2 The climate wars 3 3 Cheerleaders for alarm 4 4 What consensus about the future? 6 5 Scandal after scandal 8 6 The democratisation of science 10 7 Clearing the middle ground 11 8 Making excuses for failed predictions 13 9 The harm to science 14 About the author Matt Ridley is one of the world’s foremost science writers. -

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

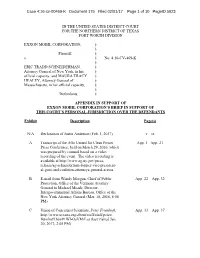

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

Private Family Portrait Collections in the North East Wednesday 9 March 2011| 11.10-16.30

Private family portrait collections in the North East Wednesday 9 March 2011| 11.10-16.30 Programme 11.10 meet at Newcastle train station 11.10-11.40 coach to Blagdon Hall, Seaton Burn 11.40-13.00 Tour of the portrait collection at Blagdon Hall, led by the proprietor Matt Ridley Blagdon Hall has been owned by the same family since 1700, when it was acquired by Matthew White I (d.1716), a coal merchant, at the time of his marriage to Jane Fenwick. Their son Matthew White II (d.1750) built the present Blagdon Hall between 1720 and 1750. The Whites intermarried with their entrepreneurial coal-mining business partners, the Ridleys, who inherited the property and baronetcy of Blagdon in 1763. The family’s property, commercial interests and influence in the region steadily increased over the generations, successive Ridley baronets (invariably bearing the Christian name Matthew) represented Newcastle or North Northumberland in Parliament before being raised to the peerage in 1900. Reflecting its role on the national stage, the family’s portrait collection includes works by the leading practitioners from the eighteenth century to the present day, artists such as Mercier, Hudson, Gainsborough, Lawrence, Hoppner, Romney, Tilly Kettle, Hubert von Herkomer, Rodrigo Moynihan, William Nicholson, Rex Whistler, Derek Hill and Andrew Festing. Of exceptional interest is the early John Hamilton Mortimer portrait of Sir Matthew White Ridley (1745-1813), 2nd baronet, and his American friend Charles Pinckney (1757-1824), demonstrating the classical tastes of two men who has studied together at Westminster and at Christchurch, Oxford. The latest addition to the portrait collection depicts the present owner Matt Ridley (our host), with his father, the 4th Viscount Ridley, and his son, by Marie-Claire Kerr. -

6, 2009 158 Goya Road Portola Valley CA 94028

SYMPOSIUM ON MATT RIDLEY’S FORTHCOMING BOOK THE OPTIMIST: ECONOMIC PROGRESS AND THE EVOLUTION OF THE FUTURE VILLAGIO INN, NAPA VALLEY, CALIFORNIA MAY 4 - 6, 2009 SPONSORED BY: GRUTER INSTITUTE FOR LAW AND BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH 158 Goya Road Portola Valley CA 94028 www.gruterinstitute.org 650.854.1191 EWING MARION KAUFFMAN FOUNDATION 4801 Rockhill Road Kansas City, MO 64110 www.kauffman.org 816.932.1000 PROPERTY AND ENVIRONMENT RESEARCH CENTER 2048 Analysis Drive STE A Bozeman MT 59718 www.perc.org 406.587.9591 The Hon. Matthew White Ridley (born February 7, 1958, in Northumberland) is an English science writer, businessman and aristocrat. Ridley was educated at Eton and Magdalen College, Oxford where he received a doctorate in zoology before commencing a career in journalism. Ridley worked as the science editor of The Economist from 1984 to 1987, and was then its Washington correspondent from 1987 to 1989, and American editor from 1990 to 1992. He is the son and heir of Viscount Ridley, whose family estate is Blagdon Hall, near Cramlington, Northumberland. Ridley is married to the neuroscientist Anya Hurlbert and lives in England; he has a son and a daughter. He was the first chairman of the International Centre for Life, a science park in Newcastle. He is a governor of the Ditchley Foundation, which organizes conferences at its stately home in Oxfordshire. Topic: Progress and the Role that Exchange and Specialization Have Played in It: Symposium on Matt Ridley’s Forthcoming Book, The Bright Side (Provisional Title) Goals: To convene a highly inter-disciplinary group of scholars, business people and journalists to discuss the subject of economic progress and the role that exchange and specialization have played in it and examine and provide comments on the then-current draft of Matt Ridley’s forthcoming book, The Bright Side. -

The Run on the Rock

House of Commons Treasury Committee The run on the Rock Fifth Report of Session 2007–08 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 24 January 2008 HC 56–I [Incorporating HC 999 i–iv, Session 2006-07] Published on Saturday 26 January 2008 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £20.00 The Treasury Committee The Treasury Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of HM Treasury, HM Revenue & Customs and associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon John McFall MP (Labour, West Dunbartonshire) (Chairman) Nick Ainger MP (Labour, Carmarthen West & South Pembrokeshire) Mr Graham Brady MP (Conservative, Altrincham and Sale West) Mr Colin Breed MP (Liberal Democrat, South East Cornwall) Jim Cousins MP (Labour, Newcastle upon Tyne Central) Mr Philip Dunne MP (Conservative, Ludlow) Mr Michael Fallon MP (Conservative, Sevenoaks) (Chairman, Sub-Committee) Ms Sally Keeble MP (Labour, Northampton North) Mr Andrew Love MP (Labour, Edmonton) Mr George Mudie MP (Labour, Leeds East) Mr Siôn Simon MP, (Labour, Birmingham, Erdington) John Thurso MP (Liberal Democrat, Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross) Mr Mark Todd MP (Labour, South Derbyshire) Peter Viggers MP (Conservative, Gosport). Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. -

Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Research

Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Research... http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/22/us/ties-to-corporate-cash... http://nyti.ms/1DIYhU3 SCIENCE Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Researcher By JUSTIN GILLIS and JOHN SCHWARTZ FEB. 21, 2015 For years, politicians wanting to block legislation on climate change have bolstered their arguments by pointing to the work of a handful of scientists who claim that greenhouse gases pose little risk to humanity. One of the names they invoke most often is Wei-Hock Soon, known as Willie, a scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who claims that variations in the sun’s energy can largely explain recent global warming. He has often appeared on conservative news programs, testified before Congress and in state capitals, and starred at conferences of people who deny the risks of global warming. But newly released documents show the extent to which Dr. Soon’s work has been tied to funding he received from corporate interests. He has accepted more than $1.2 million in money from the fossil-fuel industry over the last decade while failing to disclose that conflict of interest in most of his scientific papers. At least 11 papers he has published since 2008 omitted such a disclosure, and in at least eight of those cases, he appears to have violated ethical guidelines of the journals that published his work. The documents show that Dr. Soon, in correspondence with his corporate funders, described many of his scientific papers as “deliverables” that he completed in exchange for their money. -

8 November 2016 Programme

Programme 8 November 2016 BAFTA, London Huxley Summit Agenda 2016 3 Contents Agenda Agenda page 3 08:30 Registration Chapters page 4 09:00 Chapter 1: State of the nation Trust in the 21st Century page 6 Why trust matters page 8 10:30 Coffee and networking Speakers page 12 11:10 Chapter 2: Who do we trust? Partners page 18 12:20 Lunch and networking Attendees page 19 Round table on corporate sponsored research Round table on reasons for failure 13:50 Chapter 3: Who will we trust? 15:20 Coffee and networking 16:00 Chapter 4: Who should we trust? 17:45 Closing remarks 18:00 Drinks reception A film crew and photographer will be present at the Huxley Summit. If you do not wish to be filmed or photographed, please speak to a member of the team at British Science Association. We encourage attendees to use Twitter during the Summit, and we recommend you use the hashtag #HuxleySummit to follow the conversations. 4 Huxley Summit 2016 Chapters 5 Chapter 1: Chapter 2: Chapter 3: Chapter 4: State of the nation Who do we trust? Who will we trust? Who should we trust? The global events of 2016 have caused Many sections of business, politics and The public need to be engaged and Trust and good reputations are hard many people to question who they trust. public life have had a crisis of public informed on innovations in science won but easily lost. What drives How is this affecting the role of experts trust in recent years, but who do we trust and technology that are set to have consumers’ decision making and how and institutions? How can leaders from with science? And what can we learn a big impact on their lives and the can we drive trust in our businesses across politics, business, science and from the handling of different areas of world around them. -

Regulatory Enforcement Under New York's Martin Act: from Financial Fraud to Global Warming

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2018 Regulatory Enforcement Under New York's Martin Act: From Financial Fraud to Global Warming Richard A. Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Richard A. Epstein, "Regulatory Enforcement Under New York's Martin Act: From Financial Fraud to Global Warming," 14 New York University Journal of Law and Business 805 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEW YORK UNIVERSITY JOURNAL OF LAW & BUSINESS VOLUME 14 SUMMER 2018 NUMBER 3 REGULATORY ENFORCEMENT UNDER NEW YORK’S MARTIN ACT: FROM FINANCIAL FRAUD TO GLOBAL WARMING RICHARD A. EPSTEIN* INTRODUCTION ......................................... 806 I. THE UNLEASHING OF THE MARTIN ACT . 807 II. THE MARTIN ACT, THE COMMON-LAW ACTION FOR DECEIT, AND THE FEDERAL SECURITY AND EXCHANGE ACTS ................................ 819 A. The Origins of the Martin Act . 819 B. The Common Law of Deceit . 822 C. Basis of Liability: Fraud, Recklessness, Negligence, and Beyond .................................. 823 D. Statements of Fact: Materiality, Omissions, Opinions, and Predictions . 829 1. Materiality ............................... 830 2. Omissions ............................... 836 3. Statements of Fact and Opinion . 838 4. Predictions ............................... 844 E. Causation ................................... 845 F. Privity ...................................... 849 * Laurence A. Tisch Professor of Law, New York University School of Law; Peter and Kirsten Bedford Senior Fellow, the Hoover Institution; James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law Emeritus and Senior Lec- turer, the University of Chicago Law School; Visiting Scholar, the Manhattan Institute.