Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

$1.2 Million Conflict of Interest Plagues Climate Change Denial Research

$1.2 Million Conflict of Interest Plagues Climate Change Denial Research... http://natmonitor.com/2015/02/22/1-2-million-conflict-of-interest-plague... $1.2 Million Conflict of Interest Plagues Climate Change Denial Research By James Paladino, National Monitor | February 22, 2015 A recently uncovered document shows that Wei-Hok Soon, a well-known aerospace engineer, was granted over $1.2 million from fossil-fuel companies for climate research and failed to disclose a conflict of interest in his peer-reviewed publications. In Washington, climate change deniers are fighting a fierce battle to stave off energy policy reform. The latest casualty of this war of ideas is Wei-Hock Soon, a part-time employee of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Resilient to the scientific consensus that human carbon emissions are fueling gradual warming, the aerospace engineer has served as a beacon for conservative legislators. A recently uncovered document shows that Soon was granted over $1.2 million from fossil-fuel companies and failed to disclose a conflict of interest in his peer-reviewed publications. Since the Smithsonian is part of the federal government, former Greenpeace member Kert Davies legally obtained the Soon’s grant agreements through the Freedom of Information Act. Contributors include the American Petroleum Institute, the Koch brothers, Exxon Mobil and Southern Company. Several scientific papers and a congressional testimonial were termed as “deliverables,” reports The New York Times. “These proposals and contracts show debatable interventions in science literally on behalf of the Southern Company and the Kochs,” said Davies. “What it shows is the continuation of a long-term campaign by specific fossil-fuel companies and interests to undermine the scientific consensus on climate change.” These recent revelations have drawn fire from members of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center and NASA, among others. -

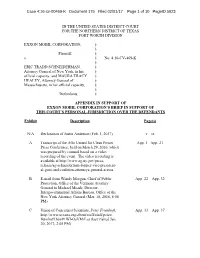

Open PDF File, 8.71 MB, for February 01, 2017 Appendix In

Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 1 of 10 PageID 5923 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS FORT WORTH DIVISION EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION, § § Plaintiff, § v. § No. 4:16-CV-469-K § ERIC TRADD SCHNEIDERMAN, § Attorney General of New York, in his § official capacity, and MAURA TRACY § HEALEY, Attorney General of § Massachusetts, in her official capacity, § § Defendants. § APPENDIX IN SUPPORT OF EXXON MOBIL CORPORATION’S BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF THIS COURT’S PERSONAL JURISDICTION OVER THE DEFENDANTS Exhibit Description Page(s) N/A Declaration of Justin Anderson (Feb. 1, 2017) v – ix A Transcript of the AGs United for Clean Power App. 1 –App. 21 Press Conference, held on March 29, 2016, which was prepared by counsel based on a video recording of the event. The video recording is available at http://www.ag.ny.gov/press- release/ag-schneiderman-former-vice-president- al-gore-and-coalition-attorneys-general-across B E-mail from Wendy Morgan, Chief of Public App. 22 – App. 32 Protection, Office of the Vermont Attorney General to Michael Meade, Director, Intergovernmental Affairs Bureau, Office of the New York Attorney General (Mar. 18, 2016, 6:06 PM) C Union of Concerned Scientists, Peter Frumhoff, App. 33 – App. 37 http://www.ucsusa.org/about/staff/staff/peter- frumhoff.html#.WI-OaVMrLcs (last visited Jan. 20, 2017, 2:05 PM) Case 4:16-cv-00469-K Document 175 Filed 02/01/17 Page 2 of 10 PageID 5924 Exhibit Description Page(s) D Union of Concerned Scientists, Smoke, Mirrors & App. -

Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Research

Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Research... http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/22/us/ties-to-corporate-cash... http://nyti.ms/1DIYhU3 SCIENCE Deeper Ties to Corporate Cash for Doubtful Climate Researcher By JUSTIN GILLIS and JOHN SCHWARTZ FEB. 21, 2015 For years, politicians wanting to block legislation on climate change have bolstered their arguments by pointing to the work of a handful of scientists who claim that greenhouse gases pose little risk to humanity. One of the names they invoke most often is Wei-Hock Soon, known as Willie, a scientist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who claims that variations in the sun’s energy can largely explain recent global warming. He has often appeared on conservative news programs, testified before Congress and in state capitals, and starred at conferences of people who deny the risks of global warming. But newly released documents show the extent to which Dr. Soon’s work has been tied to funding he received from corporate interests. He has accepted more than $1.2 million in money from the fossil-fuel industry over the last decade while failing to disclose that conflict of interest in most of his scientific papers. At least 11 papers he has published since 2008 omitted such a disclosure, and in at least eight of those cases, he appears to have violated ethical guidelines of the journals that published his work. The documents show that Dr. Soon, in correspondence with his corporate funders, described many of his scientific papers as “deliverables” that he completed in exchange for their money. -

Multiple Regression Analysis of Anthropogenic and Heliogenic Climate Drivers, and Some Cautious Forecasts a Frank Stefani

Multiple regression analysis of anthropogenic and heliogenic climate drivers, and some cautious forecasts a Frank Stefani aHelmholtz-Zentrum Dresden-Rossendorf, Institute of Fluid Dynamics, Bautzner Landstr. 400, 01328 Dresden, Germany ARTICLEINFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The two main drivers of climate change on sub-Milankovic time scales are re-assessed by means of Climate change a multiple regression analysis. Evaluating linear combinations of the logarithm of carbon dioxide Solar cycle concentration and the geomagnetic aa-index as a proxy for solar activity, we reproduce the sea surface 2 Forecast temperature (HadSST) since the middle of the 19th century with an adjusted R value of around 87 per cent for a climate sensitivity (of TCR type) in the range of 0.6 K until 1.6 K per doubling of CO2. The solution of the regression is quite sensitive: when including data from the last decade, the simultaneous occurrence of a strong El Niño on one side and low aa-values on the other side lead to a preponderance of solutions with relatively high climate sensitivities around 1.6 K. If those later data are excluded, the regression leads to a significantly higher weight of the aa-index and a correspondingly lower climate sensitivity going down to 0.6 K. The plausibility of such low values is discussed in view of recent experimental and satellite-borne measurements. We argue that a further decade of data collection will be needed to allow for a reliable distinction between low and high sensitivity values. Based on recent ideas about a quasi-deterministic planetary synchronization of the solar dynamo, we make a first attempt to predict the aa-index and the resulting temperature anomaly for various typical CO2 scenarios. -

Hockey Stick’ Global Warming’S Latest Brawl

spotlight No. 281 – February 25, 2006 BREAKING THE ‘HOCKEY STICK’ Global Warming’s Latest Brawl S U M M A R Y : Evidence from throughout the world shows that the plan- et was relatively warm 1,000 years ago during the Medieval Warm Period and relatively cold 500 years ago during the Little Ice Age. When the 1°C (1.8°F) of global warming of the past 100 years is considered in the context of climate variability of the last 1,000 years, the recent warming looks quite natural and nothing out of the ordinary. In 2001, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change prominently featured an important graph of north- ern hemispheric temperatures over the past 1,000 years, and the plot resem- bled a hockey stick. This same graph was recently highlighted in testimony to the North Carolina Legislative Commission on Climate Change. In this graph, the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age disappeared, and after 900 years of nearly steady temperatures, warming dominates the most recent 100 years. The new “hockey stick” depiction makes the recent warming look high- ly unnatural, thereby lending credence to the argument that human activities are the driving force behind global warming. The fights over the hockey stick have been among the most vicious in the two decades of heated debate over global warming. n recent months the issue of global warming has become a focus of at- tention for North Carolina policy makers. In 2005 the General Assembly established a commission on climate change to determine if the state can iadopti policies that would generate net benefits in mitigating possible global warming. -

Climate of Fear: How the Most Privileged Voices in America Have Made Climate Change Denial Mainstream Duncan B

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Student Theses 2015-Present Environmental Studies Spring 5-12-2016 Climate of Fear: How the Most Privileged Voices in America Have Made Climate Change Denial Mainstream Duncan B. Magidson Fordham University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/environ_2015 Recommended Citation Magidson, Duncan B., "Climate of Fear: How the Most Privileged Voices in America Have Made Climate Change Denial Mainstream" (2016). Student Theses 2015-Present. 30. https://fordham.bepress.com/environ_2015/30 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses 2015-Present by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Climate of Fear: How the Most Privileged Voices in America Have Made Climate Change Denial Mainstream Source: C-SPAN.org Duncan Magidson Senior Thesis Environmental Studies Spring 2016 !1 Abstract Climate change is a serious threat to the continued existence of human civilization. Despite this, the United States has yet to pass meaningful legislation to cub greenhouse gas emissions. Although tackling environmental issues once had a broad bipartisan support, the issue of climate change has driven a wedge between Democratic and Republican voters and politicians. Consequently, the United States finds itself deadlocked in the political sphere, unable to come together on any real strategies to adapt to the realities of a changing world. The driving force behind the lack of American action on climate change is the persistence of denial. Climate change denial appeals to those who hold a privileged position in American society. -

Global Temperature Change

Global Temperature Change George H. Holliday, PhD., P.E., BCEE, ASME Life Fellow Holliday Environmental Services, Inc. Abstract This study was initiated to review the existing technical literature regarding the possibility of anthropogenic carbon dioxide releases causing climate change. The literature search demonstrates no peer reviewed evidence exists, except computer climate simulations, supporting the concept of man-generated carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases causing increased global temperature. Most reports contain statements, without technical support or reference, regarding the need to control carbon dioxide e.g., “The use of these fossil fuels results in the release of carbon dioxide (CO2), which is widely believed to contribute to global climate change.” (USDOE, 2007). On the contrary, the existing technical literature report cyclic variations in climate temperature change for about 2 million years. In part, this conclusion is supported, by oxygen-28 to oxygen-16 gas ratios from analyses of ice cores covering a period of 250,000 years. The literature search leads to the conclusion anthropogenic carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions do not result in climate temperature increases. Introduction The earth’s climate forever changes in a predicable cyclic manner, apparently dictated by solar activity, Bond et al. (2001). We know Romans recorded climate warming between 200 BC and 600 AD, Lamb (1977a). In Europe, between 600 and 1300 AD, the Medieval Warming occurred. The Little Ice Age (1300 to 1850 AD) is dramatically documented by tax records of the abandonment of Greenland by the Norse population in about 1300 after nearly 300 years of moderate temperatures, when farming prospered. -

Sprievodca Svetom Vedeckého Publikovania Učebný Text Pre Kurz Publikačný Poradca

0 Centrum vedecko-technických informácií SR, Bratislava Sprievodca svetom vedeckého publikovania Učebný text pre kurz Publikačný poradca Jitka Dobbersteinová – Simona Hudecová – Zuzana Stožická Bratislava, 2019 1 Názov Sprievodca svetom vedeckého publikovania Podnázov Učebný text pre kurz Publikačný poradca Autori Mgr. Jitka Dobbersteinová PhDr. Simona Hudecová RNDr. Zuzana Stožická, PhD. Recenzenti doc. Mgr. Radoslav Harman, PhD., Fakulta matematiky, fyziky a informatiky Univerzity Komenského PhDr. Ľubica Jedličková, PhD., Slovenská poľnohospodárska knižnica Prof. RNDr. Vladimír Kováč, CSc., Prírodovedecká fakulta Univerzity Komenského Korektorka Mgr. Lucia Nižníková Vydalo Vydavateľstvo otvorenej vedy, Centrum vedecko-technických informácií SR, Bratislava Rok vydania 2019 prvé vydanie Tento učebný text (s výnimkou označených ilustrácií, ktoré sú použité so súhlasom majiteľa autorských práv) je šírený pod licenciou Creative Commons 4.0 – Atribution CC BY, ktorá umožňuje voľné používanie diela za predpokladu uvedenia mien autorov. Obálka Ing. Pavol Martinický Creative Commons 4.0 – Atribution-Non Commercial CC BY-NC (nekomerčné používanie diela za predpokladu uvedenia autora) ISBN 978-80-89965-17-5 2 Názov Sprievodca svetom vedeckého publikovania Podnázov Učebný text pre kurz Publikačný poradca Autori Jitka Dobbersteinová, Simona Hudecová, Zuzana Stožická Recenzenti doc. Mgr. Radoslav Harman, PhD. PhDr. Ľubica Jedličková, PhD. prof. RNDr. Vladimír Kováč, CSc. Počet AH 19 AH Náklad online Vydalo Vydavateľstvo otvorenej vedy, Centrum vedecko-technických -

Kconstraints on VARIABILITY of BRIGHTNESS and SURFACE MAGNETISM on TIME SCALES of DECADES to CENTURIES in the SUN and SUN-LIKE

--4. kCONSTRAINTS ON VARIABILITY OF BRIGHTNESS AND SURFACE MAGNETISM ON TIME SCALES OF DECADES TO CENTURIES IN THE SUN AND SUN-LIKE STARS: A SOURCE OF POTENTIAL TERRESTRIAL CLIMATE VARIABILITY NASA Grant NAG5-7635 Annual Report For the period 1 August 2000 to 31 July 2001 Principal Investigator Sallie L. Baliunas October 2001 Prepared for National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, D.C. 205.16 Smithsonian Institution Astrophysical Obserx_tory Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory is a member of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics The NASA Technical Officer for this Grant is James Sharber, 075.0, 300 E Street, SW/SR, Washington, DC 20546. Constraints on variability of brightness and surface magnetism on time scales of decades to centuries in the sun and sun-like stars: A source of potential terrestrial climate variability NAG5-7635 The following summarizes the most important results of our research: • Conciliation of solar and stellar photometric variability. Previous research by us and colleagues (Lockwood et al. 1992; Radick et al. 1998) suggested that the Sun might at present be showing unusually low photometric variability compared to other sun-like stars. Those early results would question the suitability of the technique of using sun-like stars as proxies for solar irradiance change on time scales of decades to centuries. How- ever, our results indicate the contrary: the Sun's observed short-term (seasonal) and long- term (year-to-year) brightness variations closely agree with observed brightness variations in stars of similar mass and age. These results were presented at the March 2000 workshop held in Tucson for investigators of this program. -

A Weak Solar Maximum, a Major Volcanic Eruption, and Possibly

MayJun13_22 4/11/03 5:26 PM Page 13 Year Without a Summer A weak solar maximum, a major volcanic eruption, and possibly even the wobbling of the Sun conspired to make the summer of 1816 one of the most miserable ever recorded. by Willie Soon and Steven H.Yaskell MayJun13_22 4/11/03 5:26 PM Page 14 Sunspots are manifestations of solar magnetic activity. In general, the more sunspots there are, the more active the Sun is. Ironically, the Sun is usually brighter when a large number of sunspots mar its visible surface. Courtesy of William C. Livingston (Kitt Peak National Solar Observatory). 200 Mounder MinimMinimumum Dolton MinimumMinimum 150 (c(c.. 1645 – 1715) (c(c.. 1795 - 1823) 100 50 0 1650 1700 1750 1800 1850 1900 1950 2000 This graph shows the annual count of sunspots from 1610 to 2000. Sunspot cycles average 11 years in length. But notice the deep drop in sunspot numbers dur- ing the Maunder and Dalton minima. Both minima were associated with global cooling. Courtesy of Tom Ford. Data courtesy of David Hathaway (NASA/MSFC). he year 1816 is still known to that was responsible for at least 70 years of Maunder minima, the Sun shifted its place scientists and historians as “eigh- abnormally cold weather in the Northern in the solar system — something it does teen hundred and froze to death” Hemisphere. The Maunder Minimum every 178 to 180 years. During this cycle, the or the “year without a summer.” It interval is sandwiched within an even better Sun moves its position around the solar was the locus of a period of known cool period known as the Little Ice system’s center of mass. -

Work of Prominent Climate Change Denier Was Funded by Energy Industry | Environment | the Guardian

05/11/2016 Work of prominent climate change denier was funded by energy industry | Environment | The Guardian Work of prominent climate change denier was funded by energy industry Willie Soon is researcher at Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics Documents: Koch brothers foundation among groups that gave total of $1.25m Suzanne Goldenberg, US environment correspondent Saturday 21 February 2015 21.32 GMT A prominent academic and climate change denier’s work was funded almost entirely by the energy industry, receiving more than $1.2m from companies, lobby groups and oil billionaires over more than a decade, newly released documents show. Over the last 14 years Willie Soon, a researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics, received a total of $1.25m from Exxon Mobil, Southern Company, the American Petroleum Institute (API) and a foundation run by the ultra-conservative Koch brothers, the documents obtained by Greenpeace through freedom of information filings show. According to the documents, the biggest single funder was Southern Company, one of the country’s biggest electricity providers that relies heavily on coal. The documents draw new attention to the industry’s efforts to block action against climate change – including President Barack Obama’s power-plant rules. Unlike the vast majority of scientists, Soon does not accept that rising greenhouse gas emissions since the industrial age are causing climate changes. He contends climate change is driven by the sun. In the relatively small universe of climate denial Soon, with his Harvard-Smithsonian credentials, was a sought after commodity. He was cited admiringly by Senator James Inhofe, the Oklahoma Republican who famously called global warming a hoax. -

Bill Mckibben Is an Activist and Architect of the Movement

THE ILLIBERAL MOVEMENT TO TURN A GENERATION AGAINST FOSSIL FUELS | 265 FORUM The following essays are written by scholars who have observed fossil fuel divestment from a variety of perspectives. Bill McKibben is an activist and architect of the movement. Matt Ridley is a scientist and popular science writer who rejects divestment movement’s claim that it can help the environment. Willie Soon, writing with Christopher Monckton of Brenchley, is a scientist who questions the extent to which anthropogenic warming will be significant or dangerous, and also questions whether divestment is practicable, necessary, or desirable. Alex Epstein is a philosopher and energy expert, best known for defending fossil fuels as a “moral” good that benefits human wellbeing. William M. Briggs is a statistician. Activists on behalf of fossil fuel divestment have sought to polarize the issue, radically reducing the options to a simple yea or nay. Polarization can be politically effective, but it impedes, rather than aids, the quest for a wise course of action. Reality rarely fits pre-packaged boxes. Prudent energy policy is no exception. In the spirit of restoring an appreciation for discourse and debate, we offer a variety of nuanced perspectives, unedited and without comment. Bill McKibben: Fossil Fuel Divestment is Moral, Financially Wise, and Strategic “The fossil fuel divestment movement,” officials of the National Association of Scholars have said, “is an exercise in futility. Its leaders fully understand that divestment, even if college trustees went along with it, would have no effect on fossil fuel companies or the environment. The divestment movement is really aimed at reinforcing the loyalty of students to the firebrands of the sustainability cause, who need a mass of followers in order to gain political leverage.” It seems to me that this assessment is wrong.