'Méliès Touch'?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Study Notes

Hugo Directed by: Martin Scorsese Certificate: U Country: USA Running time: 126 mins Year: 2011 Suitable for: primary literacy; history (of cinema); art and design; modern foreign languages (French) www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites SYNOPSIS Based on a graphic novel by Brian Selznick, Hugo tells the story of a wily and resourceful orphan boy who lives with his drunken uncle in a 1930s Paris train station. When his uncle goes missing one day, he learns how to wind the huge station clocks in his place and carries on living secretly in the station’s walls. He steals small mechanical parts from a shop owner in the station in his quest to unlock an automaton (a mechanical man) left to him by his father. When the shop owner, George Méliès, catches him stealing, their lives become intertwined in a way that will transform them and all those around them. www.hugomovie.com www.theinventionofhugocabret.com TeacHerS’ NOTeS These study notes provide teachers with ideas and activity sheets for use prior to and after seeing the film Hugo. They include: ■ background information about the film ■ a cross-curricular mind-map ■ classroom activity ideas – before and after seeing the film ■ image-analysis worksheets (for use to develop literacy skills) These activity ideas can be adapted to suit the timescale available – teachers could use aspects for a day’s focus on the film, or they could extend the focus and deliver the activities over one or two weeks. www.filmeducation.org 2 ©Film Education 2012. -

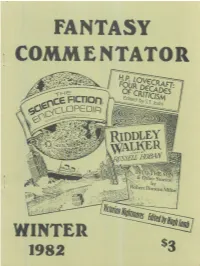

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Best Picture of the Yeari Best. Rice of the Ear

SUMMER 1984 SUP~LEMENT I WORLD'S GREATEST SELECTION OF THINGS TO SHOW Best picture of the yeari Best. rice of the ear. TERMS OF ENDEARMENT (1983) SHIRLEY MacLAINE, DEBRA WINGER Story of a mother and daughter and their evolving relationship. Winner of 5 Academy Awards! 30B-837650-Beta 30H-837650-VHS .............. $39.95 JUNE CATALOG SPECIAL! Buy any 3 videocassette non-sale titles on the same order with "Terms" and pay ONLY $30 for "Terms". Limit 1 per family. OFFER EXPIRES JUNE 30, 1984. Blackhawk&;, SUMMER 1984 Vol. 374 © 1984 Blackhawk Films, Inc., One Old Eagle Brewery, Davenport, Iowa 52802 Regular Prices good thru June 30, 1984 VIDEOCASSETTE Kew ReleMe WORLDS GREATEST SHE Cl ION Of THINGS TO SHOW TUMBLEWEEDS ( 1925) WILLIAMS. HART William S. Hart came to the movies in 1914 from a long line of theatrical ex perience, mostly Shakespearean and while to many he is the strong, silent Western hero of film he is also the peer of John Ford as a major force in shaping and developing this genre we enjoy, the Western. In 1889 in what is to become Oklahoma Territory the Cherokee Strip is just a graz ing area owned by Indians and worked day and night be the itinerant cowboys called 'tumbleweeds'. Alas, it is the end of the old West as the homesteaders are moving in . Hart becomes involved with a homesteader's daughter and her evil brother who has a scheme to jump the line as "sooners". The scenes of the gigantic land rush is one of the most noted action sequences in film history. -

Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager

Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager Special Effects Epics, 1902 – 1912 Thursday, May 15, 2008 Northwest Film Forum, Seattle, WA Co-presented by The Sprocket Society and the Northwest Film Forum Curated and program notes prepared by Spencer Sundell. Special music presentations by Climax Golden Twins and Scott Colburn. Poster design by Brian Alter. Projection: Matthew Cunningham. Mr. Sundell’s valet: Mike Whybark. Narration for The Impossible Voyage translated by David Shepard. Used with permission. (Minor edits were made for this performance.) It can be heard with a fully restored version of the film on the Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913) DVD box set (Flicker Alley, 2008). This evening’s program is dedicated to John and Carolyn Rader. The Sprocket Society …seeks to cultivate the love of the mechanical cinema, its arts and sciences, and to encourage film preservation by bringing film and its history to the public through screenings, educational activities, and our own archival efforts. www.sprocketsociety.org [email protected] The Northwest Film Forum Executive Director: Michael Seirwrath Managing Director: Susie Purves Programming Director: Adam Sekuler Associate Program Director: Peter Lucas Technical Director: Nora Weideman Assistant Technical Director: Matthew Cunningham Communications Director: Ryan Davis www.nwfilmforum.org nwfilmforum.wordpress.com THE STAR FILMS STUDIO, MONTREUIL, FRANCE The exterior of the glass-house studio Méliès built in his garden at Montreuil, France — the first movie The interior of the same studio. Méliès can be seen studio of its kind in the world. The short extension working at left (with the long stick). As you can with the sloping roof visible at far right is where the see, the studio was actually quite small. -

A Trip to the Moon As Féerie

7 FRANK KESSLER A Trip to the Moon as Féerie SHORT STORY BY JULES VERNE, first published in 1889 and describ- ing a day in the life of an American journalist in the year 2889, Aopens with the intriguing remark that “in this twenty-ninth cen- tury people live right in the middle of a continuous féerie without even noticing it.”1 This observation linking technological and scientific prog- ress to the magical world of fairy tales quite probably did not surprise Verne’s French readers at the end of the nineteenth century when widely used expressions such as “la fée électricité” emphatically conjured up the image of wondrous magic to celebrate the marvels of the modern age. However, the choice of the term “féerie,” opens up yet another dimen- sion of Verne’s metaphor, namely the realm of the spectacular. A popu- lar stage genre throughout the nineteenth century, the féerie stood for a form of theatrical entertainment combining visual splendor, fantastic plots, amazing tricks, colorful ballets, and captivating music. All these wonders, on the other hand, were not the result of any kind of magic, but of stagecraft, set design, trick techniques, and a meticulously organized mise-en-scène. Verne’s metaphor, thus, complexly intertwines magic and technology, fairy tales and progress, fantasy and science. This, precisely, is the context within which I propose to look at Méliès’s 1902 film A Trip to the Moon2—as a féerie; that is, as a film drawing from a long-standing stage tradition that had also found its way into animated pictures where Copyright © 2011. -

Syllabus Is to Be Used As a Guideline Only

**Disclaimer** This syllabus is to be used as a guideline only. The information provided is a summary of topics to be covered in the class. Information contained in this document such as assignments, grading scales, due dates, office hours, required books and materials may be from a previous semester and are subject to change. Please refer to your instructor for the most recent version of the syllabus. Fall 2018 Instructor: Dr. Ana Hedberg Olenina E-Mail: [email protected] SLC 340 Office: LL 414-D Office Hrs.: Mon. 2:30-3:30 pm & by Approaches to International Cinema appointment Overview Materials This course offers a historical survey of major film movements around the TWO BOOKS to be purchased: world, from the silent era to this day. We will explore key cinematic works, situating them in their aesthetic, cultural, and political contexts, and tracing their -- Bordwell, David and Kristin impact on the global cinematic culture. The course is organized around weekly Thompson, Film History: An Introduction. case studies of pivotal moments in national film histories – French, German, THIRD EDITION (New York: McGraw Italian, Russian, American, Japanese, Indian, Chinese, Korean, Brazilian, Hill, 2009). ISBN: 9780073386133 Senegalese, and others. We will aim to understand how and why cinematic expression around the world developed the way it did. What practices informed the emergence of stylistic innovations? What factors shaped their distribution -- Greiger, Jeffrey and R. L. Rutsky, Film and reception in the global market over time? Finally, we will critically examine Analysis: A Norton Reader. SECOND the very notion of “national” cinema – a concept that often disguises the EDITION. -

Brief History of Special/Visual Effects in Film

Brief History of Special/Visual Effects in Film Early years, 1890s. • Birth of cinema -- 1895, Paris, Lumiere brothers. Cinematographe. • Earlier, 1890, W.K.L .Dickson, assistant to Edison, developed Kinetograph. • One of these films included the world’s first known special effect shot, The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, by Alfred Clarke, 1895. Georges Melies • Father of Special Effects • Son of boot-maker, purchased Theatre Robert-Houdin in Paris, produced stage illusions and such as Magic Lantern shows. • Witnessed one of first Lumiere shows, and within three months purchased a device for use with Edison’s Kinetoscope, and developed his own prototype camera. • Produced one-shot films, moving versions of earlier shows, accidentally discovering “stop-action” for himself. • Soon using stop-action, double exposure, fast and slow motion, dissolves, and perspective tricks. Georges Melies • Cinderella, 1899, stop-action turns pumpkin into stage coach and rags into a gown. • Indian Rubber Head, 1902, uses split- screen by masking areas of film and exposing again, “exploding” his own head. • A Trip to the Moon, 1902, based on Verne and Wells -- 21 minute epic, trompe l’oeil, perspective shifts, and other tricks to tell story of Victorian explorers visiting the moon. • Ten-year run as best-known filmmaker, but surpassed by others such as D.W. Griffith and bankrupted by WW I. Other Effects Pioneers, early 1900s. • Robert W. Paul -- copied Edison’s projector and built his own camera and projection system to sell in England. Produced films to sell systems, such as The Haunted Curiosity Shop (1901) and The ? Motorist (1906). -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 469 Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Art Studies: Science, Experience, Education (ICASSEE 2020) Civilization and City Images in the Films of Georges Méliès Ekaterina Salnikova1,* 1The Media Art Department, the State Institute for Art Studies, Moscow, Russia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT The very first images of civilization and city in Georges Méliès fiction films are described in the article. His vision of "islands" of a civilization in the middle of a stony landscape and active aircraft traffic were adopted by science-fiction cinema later. In his travel films, the director creates the image of civilization not so much with the help of the spatial environment, but with references to the world of science, entertainment and spectacular urban culture. Méliès became the author of the first images of city roofs, the Middle Age city screen myth, and the confrontation of traditional city and modern technical civilization. Keywords: silent cinema, Georges Méliès, An Adventurous Automobile Trip, the Legend of Rip van Winkle, Christmas Dream, city, civilization, distraction, locations In this case, however, an image of a city is even I. INTRODUCTION more directly related to cinema, since it exists on the Studies on city images in art are an important screen in most cases as an abstract city space or even component of a modern interdisciplinary science. At the "an illusion of a city". As a rule, it is created from a State Institute for Art Studies, this issue was developed number of fragments of an urban environment, whether as part of the study on popular culture and mass media, it be nature or scenery. -

Georges Méliès's Trip to the Moon

Introduction MATTHEW SOLOMON GEORGES MÉLIÈS... is the originator of the class of cinemato- graph films which . has given new life to the trade at a time when it was dying out. He conceived the idea of portraying comical, magi- cal and mystical views, and his creations have been imitated without success ever since.... The “Trip to the Moon,” as well as... “The Astronomer’s Dream”. are the personal creations of Mr. Georges Méliès, who himself conceived the ideas, painted the backgrounds, devised the accessories and acted on the stage. —Complete Catalogue of Genuine and Original “Star” Films, 1905 If it is as a master of trick-films and fantastic spectacles that Méliès is best remembered, by no means all his pictures were of that type. —Iris Barry, Curator, Museum of Modern Art Film Library, 1939 A Trip to the Moon (1902) is certainly Georges Méliès’s best-known film, and of the tens of thousands of individual films made during cinema’s first decade, it is perhaps the most recognizable. The image of a cratered moon-face with a spaceship lodged in its eye is one of the most iconic images in all of film history and, more than a century after its initial release, the film’s story of a journey to the moon and back continues to amuse many around the world. Long recognized as a pioneering story film with an important impact on American cinema, A Trip to the Moon has also been claimed as a foundational entry in the history of several 1 © 2011 State University of New York Press, Albany 2 Matthew Solomon long-standing film genres, including science fiction, fantasy, and even the road movie.1 The film has been quoted and imitated in audiovisual works ranging from Around the World in Eighty Days (1956), to the music video for the Smashing Pumpkins’ song “Tonight, Tonight” (1996), and alluded to in literature as different as Louis-Ferdinand Céline’s nihilistic interwar novel Death on the Installment Plan (1936) and Brian Selznick’s illustrated children’s book The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007). -

Reality & Effect: a Cultural History of Visual Effects

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Communication Dissertations Department of Communication 5-3-2007 Reality & Effect: A Cultural History of Visual Effects Jae Hyung Ryu Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Ryu, Jae Hyung, "Reality & Effect: A Cultural History of Visual Effects." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2007. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/communication_diss/13 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Communication at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REALITY & EFFECT: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF VISUAL EFFECTS by JAE HYUNG RYU Under the Direction of Ted Friedman ABSTRACT The purpose of this dissertation is to chart how the development of visual effects has changed popular cinema’s vision of the real, producing the powerful reality effect. My investigation of the history of visual effects studies not only the industrial and economic context of visual effects, but also the aesthetic characteristics of the reality effect. In terms of methodology, this study employs a theoretical discourse which compares the parallels between visual effects and the discourse of modernity/postmodernity, utilizing close textual analysis to understand the symptomatic meanings of key texts. The transition in the techniques and meanings of creating visual effects reflects the cultural transformation from modernism to postmodernism. Visual effects have developed by adapting to the structural transformation of production systems and with the advance of technology.