Georges Méliès: Impossible Voyager

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Study Notes

Hugo Directed by: Martin Scorsese Certificate: U Country: USA Running time: 126 mins Year: 2011 Suitable for: primary literacy; history (of cinema); art and design; modern foreign languages (French) www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites SYNOPSIS Based on a graphic novel by Brian Selznick, Hugo tells the story of a wily and resourceful orphan boy who lives with his drunken uncle in a 1930s Paris train station. When his uncle goes missing one day, he learns how to wind the huge station clocks in his place and carries on living secretly in the station’s walls. He steals small mechanical parts from a shop owner in the station in his quest to unlock an automaton (a mechanical man) left to him by his father. When the shop owner, George Méliès, catches him stealing, their lives become intertwined in a way that will transform them and all those around them. www.hugomovie.com www.theinventionofhugocabret.com TeacHerS’ NOTeS These study notes provide teachers with ideas and activity sheets for use prior to and after seeing the film Hugo. They include: ■ background information about the film ■ a cross-curricular mind-map ■ classroom activity ideas – before and after seeing the film ■ image-analysis worksheets (for use to develop literacy skills) These activity ideas can be adapted to suit the timescale available – teachers could use aspects for a day’s focus on the film, or they could extend the focus and deliver the activities over one or two weeks. www.filmeducation.org 2 ©Film Education 2012. -

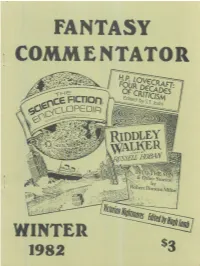

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

Classic Frenchfilm Festival

Three Colors: Blue NINTH ANNUAL ROBERT CLASSIC FRENCH FILM FESTIVAL Presented by March 10-26, 2017 Sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation A co-production of Cinema St. Louis and Webster University Film Series ST. LOUIS FRENCH AND FRANCOPHONE RESOURCES WANT TO SPEAK FRENCH? REFRESH YOUR FRENCH CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE? CONTACT US! This page sponsored by the Jane M. & Bruce P. Robert Charitable Foundation in support of the French groups of St. Louis. Centre Francophone at Webster University An organization dedicated to promoting Francophone culture and helping French educators. Contact info: Lionel Cuillé, Ph.D., Jane and Bruce Robert Chair in French and Francophone Studies, Webster University, 314-246-8619, [email protected], facebook.com/centrefrancophoneinstlouis, webster.edu/arts-and-sciences/affiliates-events/centre-francophone Alliance Française de St. Louis A member-supported nonprofit center engaging the St. Louis community in French language and culture. Contact info: 314-432-0734, [email protected], alliancestl.org American Association of Teachers of French The only professional association devoted exclusively to the needs of French teach- ers at all levels, with the mission of advancing the study of the French language and French-speaking literatures and cultures both in schools and in the general public. Contact info: Anna Amelung, president, Greater St. Louis Chapter, [email protected], www.frenchteachers.org Les Amis (“The Friends”) French Creole heritage preservationist group for the Mid-Mississippi River Valley. Promotes the Creole Corridor on both sides of the Mississippi River from Ca- hokia-Chester, Ill., and Ste. Genevieve-St. Louis, Mo. Parts of the Corridor are in the process of nomination for the designation of UNESCO World Heritage Site through Les Amis. -

Fantasies of the Institution: the Films of Georges Franju and Ince's

Film-Philosophy 11.3 December 2007 Fantasies of the Institution: The Films of Georges Franju and Ince’s Georges Franju Michael du Plessis University of Southern California Kate Ince (2005) Georges Franju Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719068282 172 pp. With the exception of Eyes Without a Face (Les yeux sans visage, 1960) and Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes, 1948), almost none of Georges Franju’s 14 short films and 8 features is currently available in the US on DVD or video, where he is now known only, if at all, as the director of a scandalously unwatchable documentary about the abattoirs of Paris and a moody (but supposedly minor) horror film about a deranged doctor who tries to graft a new face onto his disfigured daughter. Given the oblivion that surrounds this director in English-speaking countries, Kate Ince’s recent monograph on Franju in Manchester’s French Film Directors series (which includes studies of directors as varied as Georges Méliès, Jean Renoir, Marguerite Duras, and Claire Denis) serves, at the very least, as a new consideration of a significant figure in cinema history. Ince emphasises that Franju’s links to cinema as an institution go beyond his own films: he was a co-founder with Henri Langlois in 1936 of the Cinémathèque française and served as secretary of the Féderation Internationale des Archives du Film. While his involvement with the Cinémathèque may not have remained as central as it was at the beginning, Franju was made an honorary artistic director of the Cinémathèque in the last decade of his life (Ince, 2005, 1). -

Cinema and Pedagogy in France, 1909-1930 Casiana Elena Ionita Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Re

The Educated Spectator: Cinema and Pedagogy in France, 1909-1930 Casiana Elena Ionita Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 Casiana Elena Ionita All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Educated Spectator: Cinema and Pedagogy in France, 1909-1930 Casiana Elena Ionita This dissertation draws on a wide range of sources (including motion pictures, film journals, and essays) in order to analyze the debate over the social and aesthetic role of cinema that took place in France from 1909 to 1930. During this period, as the new medium became the most popular form of entertainment, moralists of all political persuasions began to worry that cinematic representations of illicit acts could provoke social unrest. In response, four groups usually considered antagonistic — republicans, Catholics, Communists, and the first film avant- garde known as the Impressionists — set out to redefine cinema by focusing particularly on shaping film viewers. To do so, these movements adopted similar strategies: they organized lectures and film clubs, published a variety of periodicals, commissioned films for specific causes, and screened commercial motion pictures deemed compatible with their goals. Tracing the history of such projects, I argue that they insisted on educating spectators both through and about cinema. Indeed, each movement sought to teach spectators of all backgrounds how to understand the new medium of cinema while also supporting specific films with particular aesthetic and political goals. Despite their different interests, the Impressionists, republicans, Catholics, and Communists all aimed to create communities of viewers that would learn a certain way of decoding motion pictures. -

Science Fiction Films of the 1950S Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 "Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s Bonnie Noonan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Noonan, Bonnie, ""Science in skirts": representations of women in science in the "B" science fiction films of the 1950s" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3653. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3653 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. “SCIENCE IN SKIRTS”: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN SCIENCE IN THE “B” SCIENCE FICTION FILMS OF THE 1950S A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Bonnie Noonan B.G.S., University of New Orleans, 1984 M.A., University of New Orleans, 1991 May 2003 Copyright 2003 Bonnie Noonan All rights reserved ii This dissertation is “one small step” for my cousin Timm Madden iii Acknowledgements Thank you to my dissertation director Elsie Michie, who was as demanding as she was supportive. Thank you to my brilliant committee: Carl Freedman, John May, Gerilyn Tandberg, and Sharon Weltman. -

Columbia Chronicle College Publications

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Columbia Chronicle College Publications 11-9-1992 Columbia Chronicle (11/09/1992) Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle Part of the Journalism Studies Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Chicago, "Columbia Chronicle (11/9/1992)" (November 9, 1992). Columbia Chronicle, College Publications, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/cadc_chronicle/158 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the College Publications at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Columbia Chronicle by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. T H E C 0 L U M B I A C 0 L L E "G E HRONICLE VOWME 26 NUMBER 7 THE EYES AND EARS OF COLUMBIA NOVEMBER 9, 1992 School to undergo ;major metamorphosis By Bum.ey Simpson slor'e remaining in the lobby. · Columbia's computer main SJII#Wrilter The jouma1ism and liler.ll arts frame and telecommunicati departments would also move Cl!l1fle£ are on the fifth floor there. Columbia will lose nearly into the Ton:o. Gall said movingthose would be $ID).(XX) a yearm rent at theTOI'CO "'n the Michigan building the tremendously expensive and buikmgwhen theStatec:illinois school plans to put a student difficult. IDIM!SoutmJure 19'X servicEs renter on the second And, even though Columbia That's what the Dlinois Depart floor by moving the Student Life recently CiDlCEied li!Oclasses due ment of Public Aid pays to offices and the Underground ID low enrollmmt, there are de OIDipy six floors in the 624 s. -

Chicago Jazz Visionaries Mike Reed and Jason Adasiewicz Perform Musical Alchemy in New Myth/Old Science, Transforming Discarde

Bio information: LIVING BY LANTERNS Title: NEW MYTH/OLD SCIENCE (Cuneiform Rune 345) Format: CD / LP Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / AVANT-JAZZ Chicago Jazz Visionaries Mike Reed and Jason Adasiewicz Perform Musical Alchemy in New Myth/Old Science, Transforming Discarded Sun Ra Rehearsal Tape Into Improvisational Gold with their group Living By Lanterns, An All-Star Nine-Piece Ensemble, Featuring a Mighty Cast of Young Chicago & New York Masters According to some versions of String Theory, ours is but one of an infinite number of universes. But you would need to dig deeply into the cosmological haystack before encountering a project as extraordinary and unlikely as New Myth/Old Science, which brings together an incandescent cast of Chicago and New York improvisers to explore music inspired by a previously unknown recording of Sun Ra. In the hands of drummer Mike Reed and vibraphonist Jason Adasiewicz, who are both invaluable and protean creative forces on Chicago’s vibrant new music scene, Ra’s informal musings serve as a portal for their cohesive but multi-dimensional combo, newly christened Living By Lanterns. Commissioned by Experimental Sound Studio (ESS), the music is one of several projects created in response to material contained in ESS’s vast Sun Ra/El Saturn Audio Archive. Rather than a Sun Ra tribute, Reed and Adasiewicz have crafted a melodically rich, harmonically expansive body of themes orchestrated from fragments extracted from a rehearsal tape marked “NY 1961,” featuring Ra on electric piano, John Gilmore on tenor sax and flute, and Ronnie Boykins on bass. -

The Bad Ass Pulse by Martin Longley

December 2010 | No. 104 Your FREE Monthly Guide to the New York Jazz Scene aaj-ny.com The THE Bad Ass bad Pulse PLUS Mulgrew Miller • Microscopic Septet • Origin • Event Calendar Many people have spoken to us over the years about the methodology we use in putting someone on our cover. We at AllAboutJazz-New York consider that to be New York@Night prime real estate, if you excuse the expression, and use it for celebrating those 4 musicians who have that elusive combination of significance and longevity (our Interview: Mulgrew Miller Hall of Fame, if you will). We are proud of those who have graced our front page, lamented those legends who have since passed and occasionally even fêted 6 by Laurel Gross someone long deceased who deserved another moment in the spotlight. Artist Feature: Microscopic Septet But as our issue count grows and seminal players are fewer and fewer, we must expand our notion of significance. Part of that, not only in the jazz world, has by Ken Dryden 7 been controversy, those players or groups that make people question their strict On The Cover: The Bad Plus rules about what is or what is not whatever. Who better to foment that kind of 9 by Martin Longley discussion than this month’s On The Cover, The Bad Plus, only the third time in our history that we have featured a group. This tradition-upending trio is at Encore: Lest We Forget: Village Vanguard from the end of December into the first days of January. 10 Bill Smith Johnny Griffin Another band that has pushed the boundaries of jazz, first during the ‘80s but now with an acclaimed reunion, is the Microscopic Septet (Artist Feature).