Georges Méliès's Trip to the Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dossier De Presse 2015

DOSSIER DE PRESSE 2015 Réalisation du dossier de presse: Blues Passions - Programmation sous réserve - Licences n°2-3 : 113040 - 11304 1 - Siret : 441 136 330 00020 - Ape : 9001Z DANIEL MOURGUET Président de Blues Passions Le monde géopolitique est en perpétuel mouvement, dans un contexte économique difficile, avec des grandes régions en construction ; et ceux qui étaient nos références artistiques vieillissent. Pour continuer à vous offrir un festival convivial, riche de découvertes, et des scènes magiques, nous devons anticiper tous ces changements. Toute l’équipe de Cognac Blues Passions, salariés et bénévoles, travaille sans relâche pour s'adapter, tout en gardant ce qui est notre savoir-faire, ce qui a fait notre succès grâce à votre présence et votre participation. Ce festival, inscrit dans le patrimoine vivant de la ville de Cognac et de son territoire, doit avancer pour garantir sa pérennité. Cette édition 2015 fait une large place à la jeunesse, à ceux qui seront nos références de demain et j’espère sincèrement que beaucoup d’entre vous diront plus tard : « j’y étais », ou « c’est à Cognac que je l’ai vu(e) la première fois ! » Au nom de toute l’équipe - les professionnels, le Conseil d’Administration et tous les bénévoles passionnés par l'événement - je vous souhaite un très bon festival 2015. © CHRISTOPHE DUCHESNAY © CHRISTOPHE DUCHESNAY MICHEL rolland Directeur et programmateur du festival Voici des mois, que nos yeux et nos oreilles sont saturés d’échos d’une éclatante absurdité, celle du comportement humain ! Répéter en boucle que tout va mal ne peut qu’inciter au découragement. -

Hugo Study Notes

Hugo Directed by: Martin Scorsese Certificate: U Country: USA Running time: 126 mins Year: 2011 Suitable for: primary literacy; history (of cinema); art and design; modern foreign languages (French) www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites SYNOPSIS Based on a graphic novel by Brian Selznick, Hugo tells the story of a wily and resourceful orphan boy who lives with his drunken uncle in a 1930s Paris train station. When his uncle goes missing one day, he learns how to wind the huge station clocks in his place and carries on living secretly in the station’s walls. He steals small mechanical parts from a shop owner in the station in his quest to unlock an automaton (a mechanical man) left to him by his father. When the shop owner, George Méliès, catches him stealing, their lives become intertwined in a way that will transform them and all those around them. www.hugomovie.com www.theinventionofhugocabret.com TeacHerS’ NOTeS These study notes provide teachers with ideas and activity sheets for use prior to and after seeing the film Hugo. They include: ■ background information about the film ■ a cross-curricular mind-map ■ classroom activity ideas – before and after seeing the film ■ image-analysis worksheets (for use to develop literacy skills) These activity ideas can be adapted to suit the timescale available – teachers could use aspects for a day’s focus on the film, or they could extend the focus and deliver the activities over one or two weeks. www.filmeducation.org 2 ©Film Education 2012. -

Paul Motian Trio I Have the Room Above Her

ECM Paul Motian Trio I Have The Room Above Her Paul Motian: drums; Bill Frisell: guitar; Joe Lovano: tenor saxophone ECM 1902 CD 6024 982 4056 (4) Release: January 2005 “Paul Motian, Bill Frisell and Joe Lovano have celebrated solo careers, but when they unite a special magic occurs, a marvel of group empathy” – The New Yorker "I Have The Room Above Her" marks the return of Paul Motian to ECM, the label that first provided a context for his compositions and his musical directions. The great American- Armenian drummer, now in his 74th year, is currently at a creative peak, and his trio, launched in 1984 with the ECM album "It Should Have Happened A Long Time Ago", has never sounded better. Motian, of course, has continued to be an important contributor to ECM recordings over the years -- see for instance his recent work with Marilyn Crispell and with Paul Bley - but hasn't recorded as a leader for the label in almost 20 years. His anthology in ECM’s Rarum series, however, released at the beginning of 2004, served as a powerful reminder of just how original his musical concept remains. As a drummer, improviser, composer of intensely lyrical melodies, and musical thinker, Paul Motian is a unique figure, and a musician of vast and varied experience. As a young man, he played with Thelonious Monk, whose idiosyncratic sense of swing (and stubborn independence from all prevailing trends) was to be a lifelong influence. Motian played with Coleman Hawkins, with Lennie Tristano, with Sonny Rollins, even, fleetingly, with John Coltrane. -

Chesley Bonestell: Imagining the Future Privacy - Terms By: Don Vaughan | July 20, 2018

HOW PRINT MYDESIGNSHOP HOW DESIGN UNIVERSITY EVENTS Register Log In Search DESIGN TOPICS∠ DESIGN THEORY∠ DESIGN CULTURE∠ DAILY HELLER REGIONAL DESIGN∠ COMPETITIONS∠ EVENTS∠ JOBS∠ MAGAZINE∠ In this roundup, Print breaks down the elite group of typographers who have made lasting contributions to American type. Enter your email to download the full Enter Email article from PRINT Magazine. I'm not a robot reCAPTCHA Chesley Bonestell: Imagining the Future Privacy - Terms By: Don Vaughan | July 20, 2018 82 In 1944, Life Magazine published a series of paintings depicting Saturn as seen from its various moons. Created by a visionary artist named Chesley Bonestell, the paintings showed war-weary readers what worlds beyond our own might actually look like–a stun- ning achievement for the time. Years later, Bonestell would work closely with early space pioneers such as Willy Ley and Wernher von Braun in helping the world understand what exists beyond our tiny planet, why it is essential for us to go there, and how it could be done. Photo by Robert E. David A titan in his time, Chesley Bonestell is little remembered today except by hardcore sci- ence fiction fans and those scientists whose dreams of exploring the cosmos were first in- spired by Bonestell’s astonishingly accurate representations. However, a new documen- tary titled Chesley Bonestell: A Brush With The Future aims to introduce Bonestell to con- temporary audiences and remind the world of his remarkable accomplishments, which in- clude helping get the Golden Gate Bridge built, creating matte paintings for numerous Hol- lywood blockbusters, promoting America’s nascent space program, and more. -

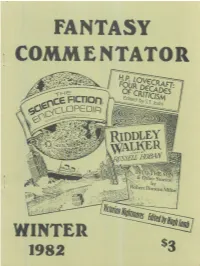

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A

Fantasy Commentator EDITOR and PUBLISHER: CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: A. Langley Searles Lee Becker, T. G. Cockcroft, 7 East 235th St. Sam Moskowitz, Lincoln Bronx, N. Y. 10470 Van Rose, George T. Wetzel Vol. IV, No. 4 -- oOo--- Winter 1982 Articles Needle in a Haystack Joseph Wrzos 195 Voyagers Through Infinity - II Sam Moskowitz 207 Lucky Me Stephen Fabian 218 Edward Lucas White - III George T. Wetzel 229 'Plus Ultra' - III A. Langley Searles 240 Nicholls: Comments and Errata T. G. Cockcroft and 246 Graham Stone Verse It's the Same Everywhere! Lee Becker 205 (illustrated by Melissa Snowind) Ten Sonnets Stanton A. Coblentz 214 Standing in the Shadows B. Leilah Wendell 228 Alien Lee Becker 239 Driftwood B. Leilah Wendell 252 Regular Features Book Reviews: Dahl's "My Uncle Oswald” Joseph Wrzos 221 Joshi's "H. P. L. : 4 Decades of Criticism" Lincoln Van Rose 223 Wetzel's "Lovecraft Collectors Library" A. Langley Searles 227 Moskowitz's "S F in Old San Francisco" A. Langley Searles 242 Nicholls' "Science Fiction Encyclopedia" Edward Wood 245 Hoban's "Riddley Walker" A. Langley Searles 250 A Few Thorns Lincoln Van Rose 200 Tips on Tales staff 253 Open House Our Readers 255 Indexes to volume IV 266 This is the thirty-second number of Fantasy Commentator^ a non-profit periodical of limited circulation devoted to articles, book reviews and verse in the area of sci ence - fiction and fantasy, published annually. Subscription rate: $3 a copy, three issues for $8. All opinions expressed herein are the contributors' own, and do not necessarily reflect those of the editor or the staff. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Catalogo Giornate Del Cinema Muto 2011

Clara Bow in Mantrap, Victor Fleming, 1926. (Library of Congress) Merna Kennedy, Charles Chaplin in The Circus, 1928. (Roy Export S.A.S) Sommario / Contents 3 Presentazione / Introduction 31 Shostakovich & FEKS 6 Premio Jean Mitry / The Jean Mitry Award 94 Cinema italiano: rarità e ritrovamenti Italy: Retrospect and Discovery 7 In ricordo di Jonathan Dennis The Jonathan Dennis Memorial Lecture 71 Cinema georgiano / Georgian Cinema 9 The 2011 Pordenone Masterclasses 83 Kertész prima di Curtiz / Kertész before Curtiz 0 1 Collegium 2011 99 National Film Preservation Foundation Tesori western / Treasures of the West 12 La collezione Davide Turconi The Davide Turconi Collection 109 La corsa al Polo / The Race to the Pole 7 1 Eventi musicali / Musical Events 119 Il canone rivisitato / The Canon Revisited Novyi Vavilon A colpi di note / Striking a New Note 513 Cinema delle origini / Early Cinema SpilimBrass play Chaplin Le voyage dans la lune; The Soldier’s Courtship El Dorado The Corrick Collection; Thanhouser Shinel 155 Pionieri del cinema d’animazione giapponese An Audience with Jean Darling The Birth of Anime: Pioneers of Japanese Animation The Circus The Wind 165 Disney’s Laugh-O-grams 179 Riscoperte e restauri / Rediscoveries and Restorations The White Shadow; The Divine Woman The Canadian; Diepte; The Indian Woman’s Pluck The Little Minister; Das Rätsel von Bangalor Rosalie fait du sabotage; Spreewaldmädel Tonaufnahmen Berglund Italianamerican: Santa Lucia Luntana, Movie Actor I pericoli del cinema / Perils of the Pictures 195 Ritratti / Portraits 201 Muti del XXI secolo / 21st Century Silents 620 Indice dei titoli / Film Title Index Introduzioni e note di / Introductions and programme notes by Peter Bagrov Otto Kylmälä Aldo Bernardini Leslie Anne Lewis Ivo Blom Antonello Mazzucco Lenny Borger Patrick McCarthy Neil Brand Annette Melville Geoff Brown Russell Merritt Kevin Brownlow Maud Nelissen Günter A. -

The Coming of Sound Film and the Origins of the Horror Genre

UNCANNY BODIES UNCANNY BODIES THE COMING OF SOUND FILM AND THE ORIGINS OF THE HORROR GENRE Robert Spadoni UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS BERKELEY LOS ANGELES LONDON University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more informa- tion, visit www.ucpress.edu. A previous version of chapter 1 appeared as “The Uncanny Body of Early Sound Film” in The Velvet Light Trap 51 (Spring 2003): 4–16. Copyright © 2003 by the University of Texas Press. All rights reserved. The cartoon on page 122 is © The New Yorker Collection 1999 Danny Shanahan from cartoonbank.com. All rights reserved. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Spadoni, Robert. Uncanny bodies : the coming of sound film and the origins of the horror genre / Robert Spadoni. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-520-25121-2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-520-25122-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Horror films—United States—History and criticism. 2. Sound motion pictures—United States— History and criticism. I. Title. pn1995.9.h6s66 2007 791.43'6164—dc22 2006029088 Manufactured in the United States -

Chapter Fourteen Men Into Space: the Space Race and Entertainment Television Margaret A. Weitekamp

CHAPTER FOURTEEN MEN INTO SPACE: THE SPACE RACE AND ENTERTAINMENT TELEVISION MARGARET A. WEITEKAMP The origins of the Cold War space race were not only political and technological, but also cultural.1 On American television, the drama, Men into Space (CBS, 1959-60), illustrated one way that entertainment television shaped the United States’ entry into the Cold War space race in the 1950s. By examining the program’s relationship to previous space operas and spaceflight advocacy, a close reading of the 38 episodes reveals how gender roles, the dangers of spaceflight, and the realities of the Moon as a place were depicted. By doing so, this article seeks to build upon and develop the recent scholarly investigations into cultural aspects of the Cold War. The space age began with the launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, by the Soviet Union on October 4, 1957. But the space race that followed was not a foregone conclusion. When examining the United States, scholars have examined all of the factors that led to the space technology competition that emerged.2 Notably, Howard McCurdy has argued in Space and the American Imagination (1997) that proponents of human spaceflight 1 Notably, Asif A. Siddiqi, The Rocket’s Red Glare: Spaceflight and the Soviet Imagination, 1857-1957, Cambridge Centennial of Flight (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) offers the first history of the social and cultural contexts of Soviet science and the military rocket program. Alexander C. T. Geppert, ed., Imagining Outer Space: European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012) resulted from a conference examining the intersections of the social, cultural, and political histories of spaceflight in the Western European context. -

Chinese International Students Talk Coronavirus Outbreak

VOLUME 104, ISSUE NO. 18 | STUDENT-RUN SINCE 1916 | RICETHRESHER.ORG | WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 19, 2020 FEATURES Candidates argue efficacy Chinese of SA at Thresher debate international RYND MORGAN students talk ASST. NEWS EDITOR Student Association internal vice president candidate Kendall Vining and write-in IVP coronavirus candidate Ashley Fitzpatrick debated the functions of roles within the SA and the SA’s relationship to the student body, and presidential candidate Anna Margaret Clyburn discussed similar issues in the SA Election Town Hall and Debate on Monday, Feb. 17, hosted by the Thresher. outbreak During the debate, Fitzpatrick said that she would be prepared to stand up to and confront Rice administration when their interests conflicted with the student body’s KELLY LIAO interests. Fitzpatrick, the Martel College SA senator, said that she had experience THRESHER STAFF directly confronting administration figures such as Dean of Undergraduates Bridget Gorman and would be willing to confront entities like the Rice Management As Chinese families around the Company, even if it meant that the administration might disown the SA as a world prepared for the Lunar New legitimate campus body. Year, the Chinese city Wuhan, with “If anything, I think that that would make the SA stronger,” Fitzpatrick, a a population of 11 million, prepared sophomore, said. “I am very much prepared to continue to stand up for the for something darker: announcing a student body.” quarantine to contain the unexpected Vining, a former Martel New Student Representative, said that she outbreak of the novel coronavirus. would be willing to confront power structures within the SA itself by Fears for family back home put a reforming the NSR role to empower students in that role. -

Die Letzten Ca. 1000 Einträge Aus Der Gesamtliste (Stand 01.10.2021)

www.jukeboxrecords.de - die letzten ca. 1000 Einträge aus der Gesamtliste (Stand 01.10.2021) Best.Nr. Name A B Kat.Nr. Land Cover/Zst. Platte/Zst. LP/EP/Si Jahr Label VK Preis 76961 1910 Fruitgum Co. Goody Goody Gumdrops Candy Kisses 201025 D 2+ 1- Si 68 Buddah 4,00 76845 1910 Fruitgum Co. May I Take A Giant Step (Into Your Heart)(Poor Old) Mr. Jensen BDA39 US LC 2 Si 68 Buddah 1,25 78154 5000 Volts (Airbus) I'm On Fire Bye Love EPC3359 D 2+ 2- Si 75 Epic 1,50 76270 53rd & 3rd & The Sound Of ShagChick-A-Boom Kingmaker 2012002 D LC 2 Si 75 UK Records 1,25 77931 Abba Does Your Mother Know Kisses Of Fire 2001881 D 2-woc 2 Si 79 Polydor 1,75 77915 Abba Head Over Heals The Visitors 2002122 D 2+ 2+ Si 81 Polydor 1,75 78139 Abba I Have A Dream Take A Chance On Me(live) 2001931 D 2- 2- Si 79 Polydor 1,50 77929 Abba Money Money Money Crazy World 2001696 D 2woc 2 Si 76 Polydor 1,75 78713 Abba One Of Us Should I love Or Cry 2002113 D 2- 2- Si 81 Polydor 1,50 78560 Abba Summer Night City Medley 2001810 D 2 2+ Si 78 Polydor 1,50 76316 Abba Take A Chance On Me I'm A Marionette 2001758 D 2 2+ Si 77 Polydor 2,00 76036 Abba The Name Of The Game I Wonder 2001742 D 2- 2 Si 77 Polydor 1,50 78045 Abba The Winner Takes It All Elaine 456460 DDR 2+ 2+ Si 80 Amiga 2,00 77052 Abba Under Attack You Owe Me One 2002204 D 1- 2+ Si 82 Polydor 1,50 75689 Abba Voulez-Vous Angeleyes 2001899 D 2+ 2- Si 79 Polydor 1,50 77328 Abba Waterloo Watch Out 2040114 D 3 2- Si 74 Polydor 1,75 78704 Abba Waterloo Watch Out 2040114 D 2+ 2+ Si 74 Polydor 2,50 78308 Abdul, Paula Forever Your Girl Next To You 112244100 D 2+ 2+ Si 89 Virgin 1,50 77104 Adam & The Ants Stand And Deliever Beat My Guest 1065 D 2 2+ Si 81 CBS 1,50 76485 Aguilar, Freddie Todo Cambia ( Everything Changes) Worries PB5849 D 2 2+ Si 80 RCA 1,50 75189 A-ha Cry Wolf Maybe, maybe 9285007 D 2 2 Si 86 WB 1,50 76269 Alligators Like The Way (You Funk With Me) instr. -

Dystopian Science Fiction Cinema In

Between the Sleep and the Dream of Reason: Dystopian Science Fiction Cinema In 1799, Francisco Goya published Los Caprichos, a collection of eighty aquatinted etchings satirising “the innumerable foibles and follies to be found in any civilized society, and … the common prejudices and deceitful practices which custom, ignorance, or self-interest have made usual.”i The most famous of them, “Capricho 43,” depicts a writer, slumped on his desk, while behind him strange creatures – a large cat, owls that shade into bats – emerge from the encompassing gloom. It is called “El sueño de la razón produce monstrous,” which is usually translated as “the sleep of reason produces monsters,” but could as easily be rendered “the dream of reason produces monsters.” In that ambiguous space – between reason’s slumber unleashing unreason and reason becoming all that there is – dystopia lies. In 1868, John Stuart Mill coined the word “dystopia” in a parliamentary speech denouncing British government policy in Ireland. Combining the Greek dys (bad) and topos (place), it plays on Thomas More’s “utopia,” itself a Greek pun: “ou” plus “topos” means “nowhere,” but “ou” sounds like “eu,” which means “good,” so the name More gave to the island invented for his 1516 book, Utopia, suggests that it is also a “good place.” It remains unclear whether More actually intended readers to consider his imaginary society, set somewhere in the Americas, as better than 16th century England. But it is certainly organized upon radically different lines. Private property and unemployment (but not slavery) have been abolished. Communal dining, legalized euthanasia, simple divorces, religious tolerance and a kind of gender equality have been introduced.