Peter Hardeman Burnett's Short but Notorious Judicial Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A. -

The History of Portland's African American Community

) ) ) ) Portland City Cor¡ncil ) ) Vera Katz, Mayor ) ) EarI Blumenauer, Comrrissioner of Public Works Charlie Hales, Commissioner of Public Safety ) Kafoury, Commissioner of Public Utilities Gretchen ,) Mike Lindberg, Commissioner of Public Affairs ) ) ) Portland CitV Planning Commission ) ) ) W. Richard Cooley, President Stan Amy, Vice-President Jean DeMaster Bruce Fong Joan Brown-Kline Margaret Kirkpatrick Richard Michaelson Vivian Parker Doug Van Dyk kinted on necJrcJed Paper History of Portland's African American Community (1805-to the Present) CityofPortland Br¡reau of Planning Gretchen Kafoury, Commissioner of Public Utilities Robert E. Stacey, Jr., Planning Director Michael S. Harrison, AICP, Chief Planner, Community Planning PnojectStatr Kimberly S. Moreland, City Planner and History Project Coordinator Julia Bunch Gisler, City Planner Jean Hester, City Planner Richard Bellinger, Graphic Illustrator I Susan Gregory, Word Processor Operator Dora Asana, Intern The activity that is the subject of the publication has been frnanced in part with federal funds from the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, as provided through the Oregon State Historic Preservation Offrce. However, the õontents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of Interior. This program receives federal frnancial assistance. Under Title VI of the Civil Righti Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of L973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, nafional origin, age or handicap in its federally-assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility operated by a recipient of federal assistance, you should write to: Office for Equal Opportunity, U.S. -

Map of the Elders: Cultivating Indigenous North Central California

HIYA ‘AA MA PICHAS ‘OPE MA HAMMAKO HE MA PAP’OYYISKO (LET US UNDERSTAND AGAIN OUR GRANDMOTHERS AND OUR GRANDFATHERS): MAP OF THE ELDERS: CULTIVATING INDIGENOUS NORTH CENTRAL CALIFORNIA CONSCIOUSNESS A Thesis Submitted to the Committee on Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Science. TRENT UNIVERSITY Peterborough, Ontario, Canada © Copyright by Diveena S. Marcus 2016 Indigenous Studies Ph.D. Graduate Program September 2016 ABSTRACT Hiya ʼAa Ma Pichas ʼOpe Ma Hammako He Ma Papʼoyyisko (Let Us Understand Again Our Grandmothers and Our Grandfathers): Map of the Elders, Cultivating Indigenous North Central California Consciousness By Diveena S. Marcus The Tamalko (Coast Miwok) North Central California Indigenous people have lived in their homelands since their beginnings. California Indigenous people have suffered violent and uncompromising colonial assaults since European contact began in the 16th century. However, many contemporary Indigenous Californians are thriving today as they reclaim their Native American sovereign rights, cultural renewal, and well- being. Culture Bearers are working diligently as advocates and teachers to re-cultivate Indigenous consciousness and knowledge systems. The Tamalko author offers Indigenous perspectives for hinak towis hennak (to make a good a life) through an ethno- autobiographical account based on narratives by Culture Bearers from four Indigenous North Central California Penutian-speaking communities and the author’s personal experiences. A Tamalko view of finding and speaking truth hinti wuskin ʼona (what the heart says) has been the foundational principle of the research method used to illuminate and illustrate Indigenous North Central California consciousness. -

CURRICULUM on CITIZENSHIP Eureka!

State of California – Military Department California Cadet Corps CURRICULUM ON CITIZENSHIP Strand C1: The State of California Level 11 This Strand is composed of the following components: A. California Basics B. California Government C. California History Eureka! “California, Here I Come!” Updated: 15 Feb 2021 California Cadet Corps Strand C1: The State of California Table of Contents B. California Basics .................................................................................................................................... 3 Objectives ................................................................................................................................................. 3 B1. California State Government – Executive Branch ........................................................................... 4 B2. California State Government – Legislative Branch ......................................................................... 7 B3. California State Government – Judicial Branch .............................................................................. 8 B4. State: Bill Becomes Law .................................................................................................................. 9 B5. California Governors ..................................................................................................................... 11 B6. Voting and the Ballot Initiative Process ........................................................................................ 19 References ................................................................................................................................................. -

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Citizenship

California Cadet Corps Curriculum on Citizenship “California, Here I Come!” C1B: California Government Updated: 16 FEB 2021 CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT B1. California State Government – Executive Branch B2. California State Government – Legislative Branch B3. California State Government – Judicial Branch B4. State: Bill Becomes Law B5. California Governors B6. Voting and the Ballot Initiative Process CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT: UNIT OBJECTIVES OBJECTIVES: The desired outcome of this unit is that Cadets will be able to explain the design of the government of California and how it carries out governmental functions. Plan of Action: 1. Be able to identify the three branches of California state government and describe in general ways who makes up each branch. 2. Describe the function of the California State Cabinet. 3. Match the executive branch elected officials to the office they hold 4. Name the Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Adjutant General. 5. Describe the legislative breakdown of senators and representatives and name the ones that represent you. 6. Name the three types of state courts in California. 7. Identify the steps for a bill to become a law in California. 8. Match facts about California Governors with the Governor. 9. Identify the steps in the ballot initiative process. 10. Describe a ballot initiative. California State Government: Executive Branch OBJECTIVES: DESIRED OUTCOME (Followership) Cadets will be able to explain the design of the government of California and how it carries out governmental functions. Plan of Action: 1. Be able to identify the three branches of California state government and describe in general ways who makes up each branch. 2. Describe the function of the California State Cabinet. -

Oigon Historic Tpms REPORT I

‘:. OIGoN HIsToRIc TPms REPORT I ii Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council May, 1998 h I Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents . Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon’s Historic Trails 7 C Oregon’s National Historic Trails 11 C Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail 13 Oregon National Historic Trail 27 Applegate National Historic Trail 47 a Nez Perce National Historic Trail 63 C Oregon’s Historic Trails 75 Kiamath Trail, 19th Century 77 o Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 87 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, 1832/1834 99 C Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1833/1834 115 o Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 129 Whitman Mission Route, 1841-1847 141 c Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 183 o Meek Cutoff, 1845 199 o Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 o Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 C General recommendations 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 247 4Xt C’ Executive summary C The Board of Directors and staff of the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council present the Oregon Historic Trails Report, the first step in the development of a statewide Oregon Historic C Trails Program. The Oregon Historic Trails Report is a general guide and planning document that will help future efforts to develop historic trail resources in Oregon. o The objective of the Oregon Historic Trails Program is to establish Oregon as the nation’s leader in developing historic trails for their educational, recreational, and economic values. The Oregon Historic Trails Program, when fully implemented, will help preserve and leverage C existing heritage resources while promoting rural economic development and growth through C heritage tourism. -

The Haun's (Hawn's) Mill Massacre by C. C. A. Christensen, Oil on Canvas

The Haun’s (Hawn’s) Mill Massacre by C. C. A. Christensen, oil on canvas, part of the Mormon Panorama, a series of large paintings depicting the early history of the Church. Baugh: Jacob Hawn and the Hawn’s Mill Massacre 1 Jacob Hawn and the Hawn’s Mill Massacre: Missouri Millwright and Oregon Pioneer Alexander L. Baugh For a number of years I have had a keen interest in researching and writ- ing about the Missouri period of early Mormonism (1831–1839). This interest propelled me to write my doctoral dissertation, completed in 1996, entitled “A Call to Arms: The 1838 Mormon Defense of Northern Missouri,” which work has since been published in BYU Studies under the same title.1 Included in this study was an extensive examination of the incident generally known as the Hawn’s Mill Massacre and its aftermath. On the afternoon of October 30, 1838, an extralegal force composed of over two-hundred men, primarily from Livingston and Daviess Counties, Missouri, attacked the isolated settlement of Hawn’s Mill, situated in eastern Caldwell County, killing seventeen Latter- day Saint civilians and wounding another fourteen. This incident, part of the larger Mormon-Missouri War, is the singular most tragic event in terms of loss of life and injury enacted by an anti-Mormon element against Latter-day Saints in the Church’s history. In conducting my research about the massacre, I canvassed all the prima- ry sources available to me at the time—personal narratives and reminiscences, affidavits, newspapers, government documents, and state and local histories. -

Gov. John Downey

John Gately Downey -Timeline with Endnote Seventh Governor of California June 24 th 1827 - March 1 st 1894 Born Castlesampson Town-land Taughmaconnell Parish South County Roscommon Ireland In his own handwritten notes archived at the Bancroft Library, in Berkeley California, John Downey describes himself as being 5’ 6” tall, with a square build, fair completion, auburn hair which turned white in later years, and hazel eyes. He claims a quick manner of address, concise and to the point, and said he was very forceful. He wanted it known that even though he was a Catholic; he donated the land for the Methodist oriented University of Southern California. 1 Page 016543-OS-5-12-DHS14 John Gately Downey -Timeline with Endnote TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Subject 1 Coversheet 2 Introduction 3 to 22 Timeline, 1734 to 1949 23 John Gately Downey portrait circa 1867 24 to 32 Endnotes 2 to 13 33 to 41 Endnotes 14 to 32 42 to 52 Endnotes 32 to 57 53 to 62 Endnotes 58 to 62 63 to 79 Endnotes 62 to 79 80 to 88 Endnotes 80 to 88 89 to 95 Endnotes 89 to 95 96 to 109 Endnotes 95 to 117 110 to120 Endnotes 118 to 139 121 to 126 Endnotes 140 to 147 127 to 134 Chronicle of the builders of the commonwealth: Vol. 2. HH Bancroft 135 to138 Transcript of Governor Downey’s personal notes to Bancroft in 1888 139 to145 Excerpts from The Irish Race in California & the Pacific Coast by Hugh Quigley 146 to154 Downey relatives biography’s plus miscellaneous notes and articles 155 to 157 Bibliography 157 to 162 Web Links 163 to 177 Miscellaneous Notes 178 to 182 Civil War notes and letters 183 to 188 Notes Articles & Family tree information 189 to 217 The Story of John Gately Downey by Mark Calney 218 to 226 Miscellaneous John Gately Downey related information 2 Page 016543-OS-5-12-DHS14 John Gately Downey -Timeline with Endnote Introduction By any historical measure, the life and times of Governor John Gately Downey are recent history. -

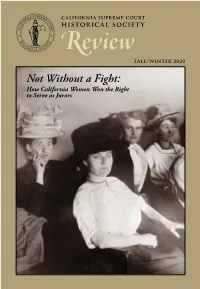

CSCHS Review Fall/Winter 2020

California Supreme Court Historical Society Review FALL/WINTER 2020 Not Without a Fight: How California Women Won the Right to Serve as Jurors Above, and on front cover: In November 1911, less than a month after the California suffrage amendment, Los Angeles County seated the first all-woman jury in the state. (Courtesy George Grantham Bain Collection and the Library of Congress.) Woman Jurors in California: Recognizing a Right of Citizenship BY COLLEEN REGAN doption of the Nineteenth Amendment to Like early struggles for the right to vote prior to the United States Constitution in August 1920, adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment, acceptance of Aextending the franchise to women, has been cel- women as jurors arrived on a state-by-state basis. Some ebrated this year with exhibits, marches and films. Less states automatically coupled jury service with the voting celebrated, but equally compelling, is the history of equal franchise, but most, including California, treated voting rights for women as jurors in civil and criminal cases. rights and jury participation as separate issues, requiring A constitutional amendment was necessary to guar- women to wage separate battles to serve as jurors.2 antee voting equality for women because, in 1874, the U.S. Supreme Court had held that the Constitution 2. In eight states (Nevada, Michigan, Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, did not guarantee a citizen the right to vote.1 Therefore, Kentucky, Ohio and Pennsylvania), “as soon as women were although women were recognized to be citizens, vot- accorded the right to vote in such states, their right to serve on ing could be restricted to men. -

Litutamautt Coim^ Fliatoriral ^Oriatg ^Umtcattcn Na.12

litUtamautt Coim^ fliatoriral ^oriatg ^uMtcattcn Na.12 0 i \ tO \ J- U I <1 \ - 0 1 m/imlf'tHt. V Fbanki. w I L s M H»S ** ■r'L Vm(* w,\ \ J*> /ta1fk*w TZh^m.'* /fa^ •/ TSnrtsM**' \ Vv^-r £. ')D rOfSZi Co. ^|inng 19BI :;->i WILLIAMSON COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY PUBLICATION Number 12 Spring 1981 Published by Williamson County Historical Society Franklin, Tennessee 1981 WILLIAMSON COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY PUBLICATION Number 12 Spring 1981 Published by the Williamson County Historical Society T. Vance Little and George F. Watson, Publication Co-Chairmen OFFICERS President Miss Mary Trim Anderson 1st Vice-President Earl J. Smith 2nd Vice-Presidents T. Vance Little and George F. Watson Treasurer Herman Major Recording Secretary Mrs. John Lester Corresponding Secretary Mrs. Thelma Richardson PUBLICATION COMMITTEE T. Vance Little Mrs. Louise G. Lynch George F. Watson Mrs. Virginia G. Watson The WILLIAMSON COUNTY HISTORICAL PUBLICATION is sent to all members of the Williamson County Historical Society. The annual membership dues are $8, which includes this publication and a frequent NEWSLETTER to all members. Correspondence concerning additional copies of the WILLIAMSON COUNTY HISTORICAL PUBLICATION should be addressed to Mrs. Clyde Lynch, Route 10, Franklin, Tennessee 37064. Contributions to future issues of the WILLIAMSON COUNTY HISTORICAL PUBLICATION should be addressed to T. Vance Little, Beech Grove Farm, Route 1, Brentwood, Tennessee 37027. Correspondence concerning membership and payment of dues should be addressed to Herman Major, Treasurer, P. 0. Box 71, Franklin, Tennessee 370614. PRESIDENT'S REPORT "A land without ruins is a land without memories a land without memories is a land without history." So wrote Abram Joseph Ryan. -

Traducción De Textos Políticos Relacionados Con El Exterminio De Los Indios Norteamericanos

This is the published version of the bachelor thesis: Tarrago Gallifa, Diana; López Guix, Juan Gabriel, dir. Traducción de textos políticos relacionados con el exterminio de los indios norteamericanos. 2015. (1202 Grau en Traducció i Interpretació) This version is available at https://ddd.uab.cat/record/146934 under the terms of the license TRADUCCIÓN DE TEXTOS POLÍTICOS RELACIONADOS CON EL EXTERMINIO DE LOS INDIOS NORTEAMERICANOS 103698 - TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO Grado en Traducción e Interpretación Curso académico 2014-2015 Estudiante: Diana Tarragó Gallifa Tutor: Gabriel López Guix 10 de junio de 2015 Facultad de Traducción e Interpretación Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona 2 Datos del TFG Título: Traducción de textos políticos relacionados con el exterminio de los indios norteamericanos Autora: Diana Tarragó Gallifa Tutor: Gabriel López Guix Centro: Facultad de Traducción e Interpretación Estudios: Grau en Traducción e Interpretación Curso académico: 2014‐15 Palabras clave Textos políticos, exterminio, indios norteamericanos, traducción, Andrew Jackson, John Ross, Peter Burnett, discursos. Resumen del TFG Este trabajo se basa en la traducción de unos fragmentos extraídos de discursos que pronunciaron Andrew Jackson (séptimo presidente de los Estados Unidos), John Ross (jefe principal de la nación cheroqui) y Peter Burnett (el primer gobernador de California), durante sus respectivos mandatos. Los tres fragmentos en cuestión tratan sobre el mismo tema desde puntos de vista muy diferentes: el trato hacia los indios. Aviso legal © Diana Tarragó Gallifa, Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona, 2015. Todos los derechos reservados. Ningún contenido de este trabajo puede ser objeto de reproducción, comunicación pública, difusión y/o transformación, de forma parcial o total, sin el permiso o la autorización de su autora.