James D. Saules and the Enforcement of the Color Line in Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890 Richard P. Matthews Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Matthews, Richard P., "Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3808. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5692 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Richard P. Matthews for the Master of Arts in History presented 4 November, 1988. Title: Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier: East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington county, 1840 - 1890. APPROVED BY MEMBE~~~ THESIS COMMITTEE: David Johns n, ~on B. Dodds Michael Reardon Daniel O'Toole The evolution of the small towns that originated in Oregon's settlement communities remains undocumented in the literature of the state's history for the most part. Those .::: accounts that do exist are often amateurish, and fail to establish the social and economic links between Oregon's frontier towns to the agricultural communities in which they appeared. The purpose of the thesis is to investigate an early settlement community and the small town that grew up in its midst in order to better understand the ideological relationship between farmers and townsmen that helped shape Oregon's small towns. -

Oregon and Manifest Destiny Americans Began to Settle All Over the Oregon Country in the 1830S

NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ Manifest Destiny Lesson 1 The Oregon Country ESSENTIAL QUESTION Terms to Know joint occupation people from two countries living How does geography influence the way in the same region people live? mountain man person who lived in the Rocky Mountains and made his living by trapping animals GUIDING QUESTIONS for their fur 1. Why did Americans want to control the emigrants people who leave their country Oregon Country? prairie schooner cloth-covered wagon that was 2. What is Manifest Destiny? used by pioneers to travel West in the mid-1800s Manifest Destiny the idea that the United States was meant to spread freedom from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean Where in the world? 54°40'N Alaska Claimed by U.S. and Mexico (Russia) Oregon Trail BRITISH OREGON 49°N TERRITORY Bo undary (1846) COUNTRY N E W S UNITED STATES MEXICO PACIFIC OCEAN ATLANTIC OCEAN When did it happen? DOPA (Discovering our Past - American History) RESG Chapter1815 13 1825 1835 1845 1855 Map Title: Oregon Country, 1846 File Name: C12-05A-NGS-877712_A.ai Map Size: 39p6 x 26p0 Date/Proof: March 22, 2011 - 3rd Proof 2016 Font Conversions: February 26, 2015 1819 Adams- 1846 U.S. and Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission is granted to reproduce for classroom use. Copyright © McGraw-Hill Education. Permission 1824 Russia 1836 Whitmans Onís Treaty gives up claim to arrive in Oregon Britain agree to Oregon 49˚N as border 1840s Americans of Oregon begin the “great migration” to Oregon 165 NAME _____________________________________________ DATE __________________ CLASS ____________ Manifest Destiny Lesson 1 The Oregon Country, Continued Rivalry in the Northwest The Oregon Country covered much more land than today’s state Mark of Oregon. -

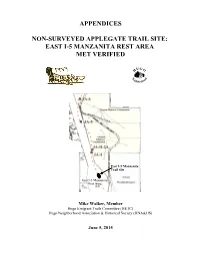

Appendices Non-Surveyed Applegate Trail Site: East I

APPENDICES NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED Mike Walker, Member Hugo Emigrant Trails Committee (HETC) Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HNA&HS) June 5, 2015 NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED APPENDICES Appendix A. Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HuNAHS) Standards for All Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix B. HuNAHS’ Policy for Document Verification & Reliability of Evidence Appendix C. HETC’s Standards: Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix D1. Pedestrian Survey of Stockpile Site South of Chancellor Quarry in the I-5 Jumpoff Joe-Glendale Project, Josephine County (separate web page) Appendix D2. Subsurface Reconnaissance of the I-5 Chancellor Quarry Stockpile Project, and Metal Detector Survey Within the George and Mary Harris 1854 - 55 DLC (separate web page) Appendix D3. May 18, 2011 Email/Letter to James Black, Planner, Josephine County Planning Department (separate web page) Appendix D4. The Rogue Indian War and the Harris Homestead Appendix D5. Future Studies Appendix E. General Principles Governing Trail Location & Verification Appendix F. Cardinal Rules of Trail Verification Appendix G. Ranking the Reliability of Evidence Used to Verify Trial Location Appendix H. Emigrant Trail Classification Categories Appendix I. GLO Surveyors Lake & Hyde Appendix J. Preservation Training: Official OCTA Training Briefings Appendix K. Using General Land Office Notes And Maps To Relocate Trail Related Features Appendix L1. Oregon Donation Land Act Appendix L2. Donation Land Claim Act Appendix M1. Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855 Appendix M2. How Accurate Were the GLO Surveys? Appendix M3. Summary of Objects and Data Required to Be Noted In A GLO Survey Appendix M4. -

The Capitol Dome

THE CAPITOL DOME The Capitol in the Movies John Quincy Adams and Speakers of the House Irish Artists in the Capitol Complex Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way A MAGAZINE OF HISTORY PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL HISTORICAL SOCIETYVOLUME 55, NUMBER 22018 From the Editor’s Desk Like the lantern shining within the Tholos Dr. Paula Murphy, like Peart, studies atop the Dome whenever either or both America from the British Isles. Her research chambers of Congress are in session, this into Irish and Irish-American contributions issue of The Capitol Dome sheds light in all to the Capitol complex confirms an import- directions. Two of the four articles deal pri- ant artistic legacy while revealing some sur- marily with art, one focuses on politics, and prising contributions from important but one is a fascinating exposé of how the two unsung artists. Her research on this side of can overlap. “the Pond” was supported by a USCHS In the first article, Michael Canning Capitol Fellowship. reveals how the Capitol, far from being only Another Capitol Fellow alumnus, John a palette for other artist’s creations, has been Busch, makes an ingenious case-study of an artist (actor) in its own right. Whether as the historical impact of steam navigation. a walk-on in a cameo role (as in Quiz Show), Throughout the nineteenth century, steam- or a featured performer sharing the marquee boats shared top billing with locomotives as (as in Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), the the most celebrated and recognizable motif of Capitol, Library of Congress, and other sites technological progress. -

Clackamas County

EXHIBIT A - Invisible Walls: Housing Discrimination in Clackamas County 94 Table of Contents A Note About This Project ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Class Bios ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 2 Project Introduction and Methods Statement …………………………………………………………………………. 3 Timeline ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 8 Historic Property Deed Research …………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Metropolitan Setting of the Suburban Zone ………………………………………………………………………….. 21 Community Highlights: - Lake Oswego ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 24 - Milwaukie ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 28 - Oregon City ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 34 Land and Conflict: The Genesis of Housing Discrimination in Clackamas County ……………………. 38 Migrant Labor in Oregon: 1958 Snapshot ………………………………………………………………………………. 41 Migrant Labor in Oregon: Valley Migrant League …………………………………………………………………… 43 Chinese in Clackamas County ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 48 Japanese in Clackamas County ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 51 Direct Violence: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 54 - Richardson Family ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 55 - Perry Ellis …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 56 Resistance in Lane County …………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 57 John Livingston ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 58 Political Structure: - Zoning in Clackamas County ………………………………………………………………………………………. 59 - Urban Growth Boundary ……………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Whitman Mission

WHITMAN MISSION NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE WASHINGTON At the fur traders' Green River rendezvous that A first task in starting educational work was to Waiilatpu, the emigrants replenished their supplies perstitious Cayuse attacked the mission on November year the two men talked to some Flathead and Nez learn the Indians' languages. The missionaries soon from Whitman's farm before continuing down the 29 and killed Marcus Whitman, his wife, and 11 WHITMAN Perce and were convinced that the field was promis devised an alphabet and began to print books in Columbia. others. The mission buildings were destroyed. Of ing. To save time, Parker continued on to explore Nez Perce and Spokan on a press brought to Lapwai the survivors a few escaped, but 49, mostly women Oregon for sites, and Whitman returned east to in 1839. These books were the first published in STATION ON THE and children, were taken captive. Except for two MISSION recruit workers. Arrangements were made to have the Pacific Northwest. OREGON TRAIL young girls who died, this group was ransomed a Rev. Henry Spalding and his wife, Eliza, William For part of each year the Indians went away to month later by Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson's Waiilatpu, "the Place of the Rye Grass," is the Gray, and Narcissa Prentiss, whom Whitman mar the buffalo country, the camas meadows, and the When the Whitmans Bay Company. The massacre ended Protestant mis site of a mission founded among the Cayuse Indians came overland in 1836, the in 1836 by Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. As ried on February 18, 1836, assist with the work. -

Trail News Fall 2018

Autumn2018 Parks and Recreation Swimming Pool Pioneer Community Center Public Library City Departments Community Information NEWS || SERVICES || INFORMATION || PROGRAMS || EVENTS City Matters—by Mayor Dan Holladay WE ARE COMMEMORATING the 175th IN OTHER EXCITING NEWS, approximately $350,000 was awarded to anniversary of the Oregon Trail. This is 14 grant applicants proposing to make improvements throughout Ore- our quarto-sept-centennial—say that five gon City utilizing the Community Enhancement Grant Program (CEGP). times fast. The CEGP receives funding from Metro, which operates the South Trans- In 1843, approximately 1,000 pioneers fer Station located in Oregon City at the corner of Highway 213 and made the 2,170-mile journey to Oregon. Washington Street. Metro, through an Intergovernmental Agreement Over the next 25 years, 400,000 people with the City of Oregon City, compensates the City by distributing a traveled west from Independence, MO $1.00 per ton surcharge for all solid waste collected at the station to be with dreams of a new life, gold and lush used for enhancement projects throughout Oregon City. These grants farmlands. As the ending point of the Ore- have certain eligibility requirements and must accomplish goals such as: gon Trail, the Oregon City community is marking this historic year ❚ Result in significant improvement in the cleanliness of the City. with celebrations and unique activities commemorating the dream- ❚ Increase reuse and recycling efforts or provide a reduction in solid ers, risk-takers and those who gambled everything for a new life. waste. ❚ Increase the attractiveness or market value of residential, commercial One such celebration was the Grand Re-Opening of the Ermatinger or industrial areas. -

Portland Blocks 178 & 212 ( 4Mb PDF )

Portland Blocks 178 & 212 Portland blocks 178 and 212 are part of the core of the city’s vibrant downtown business district and have been central to Portland’s development since the founding of the city. These blocks rest on a historical signifi cant area within the city which bridge the unique urban design district of the park blocks and the rest of downtown with its block pattern and street layout. In addition, this area includes commercial and offi ce structures along with theaters, hotels, and specialty retail outlets that testify to the economic growth of Portland’s during the twentieth century. The site of the future city of Portland, Oregon was known to traders, trappers and settlers of the 1830s and early 1840s as “The Clearing,” a small stopping place along the west bank of the Willamette River used by travellers en route between Oregon City and Fort Vancouver. In 1840, Massachusetts sea captain John Couch logged the river’s depth adjacent to The Clearing, noting that it would accommodating large ocean-going vessels, which could not ordinarily travel up-river as far as Oregon City, the largest Oregon settlement at the time. Portland’s location at the Willamette’s confl uence with the Columbia River, accessible to deep-draft vessels, gave it a key advantage over its older peer. In 1843, Tennessee pioneer William Overton and Asa Lovejoy, a lawyer from Boston, Massachusetts, fi led a land claim encompassed The Clearing and nearby waterfront and timber land. Overton sold his half of the claim to Francis W. Pettygrove of Portland, Maine. -

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

The Anglo-American Crisis Over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw

92 BC STUDIES For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw. New York: Peter Lang, 1995. xii, 240 pp. Illus. US$44.95 cloth. In the years prior to 1846, the Northwest Coast — an isolated region scarcely populated by non-Native peoples — was for the second time in less than a century the unlikely flashpoint that brought far-distant powers to the brink of war. At issue was the boundary between British and American claims in the "Oregon Country." While President James Polk blustered that he would have "54^0 or Fight," Great Britain talked of sending a powerful fleet to ensure its imperial hold on the region. The Oregon boundary dispute was settled peacefully, largely because neither side truly believed the territory worth fighting over. The resulting treaty delineated British Columbia's most critical boundary; indeed, without it there might not even have been a British Columbia. Despite its significance, though, the Oregon boundary dispute has largely been ignored by BC's historians, leaving it to their colleagues south of the border to produce the most substantial work on the topic. This most recent analysis is no exception. For Honor or Destiny: The Anglo-American Crisis over the Oregon Territory, by Donald Rakestraw, began its life as a doctoral thesis completed at the University of Alabama. Published as part of an American University Studies series, Rakestraw's book covers much the same ground as did that of his countryman Frederick Merk some decades ago. By making extensive use of new primary material, Rakestraw is able to present a fresh, succinct, and well-written chronological narrative of the events leading up to the Oregon Treaty of 1846. -

The Old Northwest and the Texas Annexation Treaty

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 7 Issue 2 Article 5 10-1969 The Old Northwest and the Texas Annexation Treaty Norman E. Tutorow Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation Tutorow, Norman E. (1969) "The Old Northwest and the Texas Annexation Treaty," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 7 : Iss. 2 , Article 5. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol7/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ea!(t Texas Historical Journal 67 THE OLD NORTHWEST AND THE TEXAS ANNEXATION TREATY NORMAN E. TUTOROW On April 22. 1844. President Tyler submitted the Texas treaty to the United States Senate. sending with it scores of official documents and a catalog of arguments in (avor of annexation.' He offered evidence of popular support within Texas itself for annexation. He also argued that Britain had designs on Texas which, if allowed to mature, would pose Ii serious threat tu the South's "peculiar institution.'" According to Tyler, the annexation of Texas would be a blessing to the whole nation. Because Texas would most likely concentrate its e.fforts on raising cotton, the North and West would find there a market fOl" horses, beef, and wheat. Among the most important of the obvious advantages was security from outside interference with the institution of slavery, especially from British abolition· ists, who were working to get Texas to abolish slavery. -

Lt. Aemilius Simpson's Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826

The Journal of the Hakluyt Society August 2014 Lt. Aemilius Simpson’s Survey from York Factory to Fort Vancouver, 1826 Edited by William Barr1 and Larry Green CONTENTS PREFACE The journal 2 Editorial practices 3 INTRODUCTION The man, the project, its background and its implementation 4 JOURNAL OF A VOYAGE ACROSS THE CONTINENT OF NORTH AMERICA IN 1826 York Factory to Norway House 11 Norway House to Carlton House 19 Carlton House to Fort Edmonton 27 Fort Edmonton to Boat Encampment, Columbia River 42 Boat Encampment to Fort Vancouver 62 AFTERWORD Aemilius Simpson and the Northwest coast 1826–1831 81 APPENDIX I Biographical sketches 90 APPENDIX II Table of distances in statute miles from York Factory 100 BIBLIOGRAPHY 101 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Fig. 1. George Simpson, 1857 3 Fig. 2. York Factory 1853 4 Fig. 3. Artist’s impression of George Simpson, approaching a post in his personal North canoe 5 Fig. 4. Fort Vancouver ca.1854 78 LIST OF MAPS Map 1. York Factory to the Forks of the Saskatchewan River 7 Map 2. Carlton House to Boat Encampment 27 Map 3. Jasper to Fort Vancouver 65 1 Senior Research Associate, Arctic Institute of North America, University of Calgary, Calgary AB T2N 1N4 Canada. 2 PREFACE The Journal The journal presented here2 is transcribed from the original manuscript written in Aemilius Simpson’s hand. It is fifty folios in length in a bound volume of ninety folios, the final forty folios being blank. Each page measures 12.8 inches by seven inches and is lined with thirty- five faint, horizontal blue-grey lines.