Characteristics of Major Scales Tips for Learning and Rehearsing Scales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

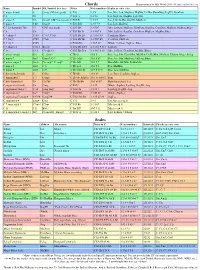

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

HOW to FIND RELATIVE MINOR and MAJOR SCALES Relative

HOW TO FIND RELATIVE MINOR AND MAJOR SCALES Relative minor and major scales share all the same notes–each one just has a different tonic. The best example of this is the relative relationship between C-major and A-minor. These two scales have a relative relationship and therefore share all the same notes. C-major: C D E F G A B C A-minor: A B C D E F G A Finding the relative minor from a known major scale (using the 6th scale degree) scale degrees: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 C-major: C D E F G A B C A-(natural) minor: A B C D E F G A A-minor starts on the 6th scale degree of C-major. This relationship holds true for ALL major and minor scale relative relationships. To find the relative minor scale from a given major scale, count up six scale degrees in the major scale–that is where the relative minor scale begins. This minor scale will be the natural minor mode. 1 2 3 4 5 6 C-D-E-F-G-A The relative minor scale can also be found by counting backwards (down) by three scale degrees in the major scale. C-major: C D E F G A B C ←←← count DOWN three scale degrees and arrive at A 1 2 3 C-B-A Finding the relative major from a known minor scale (using the 3rd scale degree) scale degrees: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 A-(natural) minor: A B C D E F G A C-major: C D E F G A B C C-major starts on the 3rd scale of A-minor. -

The Major Scale Music Sounds the Way It Does Has to Do with the Group of Notes the Composer Decided to Use

music theory for musicians and normal people by toby w. rush one of the reasons that a particular piece of The Major Scale music sounds the way it does has to do with the group of notes the composer decided to use. 2 2 , 17 bach na e bachr a magdal ian jo t a ann bas m G for se n i ann ook oh eb inuett j M no œ#œ œ œ œ œ œ &43 œ œ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ ˙. take this melody, for example... let’s first remove all the duplicate notes, regardless of which octave they’re in. œ#œ œ &43 œ œ œ œ next, let’s put the notes in alphabetical order, œ #œ œ starting on the note œ #œ œ œ œ œ that the melody sounded œ œ œ œ like it was centering on. œ œ what we end up with there are actually many is the for “palette” different types of scales, this particular piece... each with a different pattern of whole steps and half steps. œ œ œ #œ œ œ œ œ a half step is the distance between like the board on which a painter holds two adjacent keys the bits of paint being used in the painting on the piano keyboard, being created. regardless of color. in music, this “palette” is called a scale. though we usually write scales from low to high, the order is actually unimportant; it’s the notes contained in the scale that help make a piece sound the way it does. -

11-Music Scales

Scales in Music Gary Hardegree Department of Philosophy University of Massachusetts Amherst, MA 01003 1. Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 2. The Fundamental Unit – The Octave...............................................................................................2 1. An Aside on Logarithmic Scales .........................................................................................5 2. Cents and Sensibility............................................................................................................6 3. The Pythagorean Construction of the Major Scale..........................................................................7 4. Ptolemaic Tuning...........................................................................................................................10 5. Mean-Tone Temperament (Tuning by Major Thirds) ...................................................................11 6. Problems with Perfect Tuning........................................................................................................12 1. An Aside on The Circle of Fifths and the Circle of Thirds................................................14 2. Back to the Problem of Tuning by Fifths...........................................................................14 3. Ptolemaic Tuning Makes Matters Even Worse! ................................................................15 4. Mean-Tone Temperament’s Wolves..................................................................................17 -

Finding Alternative Musical Scales

Finding Alternative Musical Scales John Hooker Carnegie Mellon University October 2017 1 Advantages of Classical Scales • Pitch frequencies have simple ratios. – Rich and intelligible harmonies • Multiple keys based on underlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. – Can play all keys on instrument with fixed tuning. – Complex musical structure. • Can we find new scales with these same properties? – Constraint programming is well suited to solve the problem. 2 Simple Ratios • Acoustic instruments produce multiple harmonic partials. – Frequency of partial = integral multiple of frequency of fundamental. – Coincidence of partials makes chords with simple ratios easy to recognize. Perfect fifth C:G = 2:3 3 Simple Ratios • Acoustic instruments produce multiple harmonic partials. – Frequency of partial = integral multiple of frequency of fundamental. – Coincidence of partials makes chords with simple ratios easy to recognize. Octave C:C = 1:2 4 Simple Ratios • Acoustic instruments produce multiple harmonic partials. – Frequency of partial = integral multiple of frequency of fundamental. – Coincidence of partials makes chords with simple ratios easy to recognize. Major triad C:E:G = 4:5:6 5 Multiple Keys • A classical scale can start from any pitch in a chromatic with 12 semitone intervals. – Resulting in 12 keys. – An instrument with 12 pitches (modulo octaves) can play 12 different keys. – Can move to a different key by changing only a few notes of the scale. 6 Multiple Keys Let C major be the tonic key C 1 D#E 6 A C major b 0 notes F#G -

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale

In Search of the Perfect Musical Scale J. N. Hooker Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, USA [email protected] May 2017 Abstract We analyze results of a search for alternative musical scales that share the main advantages of classical scales: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an un- derlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. The search is based on combinatorics and a constraint programming model that assigns frequency ratios to intervals. We find that certain 11-note scales on a 19-note chromatic stand out as superior to all others. These scales enjoy harmonic and structural possibilities that go significantly beyond what is available in classical scales and therefore provide a possible medium for innovative musical composition. 1 Introduction The classical major and minor scales of Western music have two attractive characteristics: pitch frequencies that bear simple ratios to each other, and multiple keys based on an underlying chromatic scale with tempered tuning. Simple ratios allow for rich and intelligible harmonies, while multiple keys greatly expand possibilities for complex musical structure. While these tra- ditional scales have provided the basis for a fabulous outpouring of musical creativity over several centuries, one might ask whether they provide the natural or inevitable framework for music. Perhaps there are alternative scales with the same favorable characteristics|simple ratios and multiple keys|that could unleash even greater creativity. This paper summarizes the results of a recent study [8] that undertook a systematic search for musically appealing alternative scales. The search 1 restricts itself to diatonic scales, whose adjacent notes are separated by a whole tone or semitone. -

Natural Minor Scale Is Given

Minor Scales Minor scales/keys are used by composers when they wish to express a different mood than those characterized my major scales in music. Minor scales and keys conjure feelings of sorrow or tension. Minor scales also have their own unique set of intervals found between the 8 pitches in the scale. The major scale which used all white notes on the piano is the C major scale (example #1). Example #1 q Q Q l=============& _q q q q l q =l[ The minor scale which uses all white notes on the piano the scale with no sharps or flats is A minor. The C major scale and the A minor scale are related (they are cousins) because they share the same key signature, no sharps or flats. Example #2 shows that relationship very clearly. All of notes in the A minor scale are found in the C major scale with the difference between the two just the starting note or tonic. The C major scale starts on C which is its tonic and the A minor scale starts on A which is its tonic. Example #2 Î Î q Q Q Major l===============& _q q lq q q l =l[ l l q q q Î Î Minor l===============& _q _q _q q l q l =l[ The unique relationship of major and minor makes the work of studying minor simpler. As we know from the information above each major scale/key has a relative (cousin) minor that uses the same notes and key signatures however each starts on a different note (tonic). -

A LIGHTWEIGHT NOTATION for PLAYING PIANO for FUN by R.J.A

A LIGHTWEIGHT NOTATION FOR PLAYING PIANO FOR FUN by R.J.A. Buhr 1. INTRODUCTION Music notation gets in the way of the joy of making music on the piano that can be had without first spending thousands of hours at the keyboard to develop piano “wizardry,” meaning a combination of keyboard skill and mastery of music notation. The message of this document is the joy can be had, without any loss of musical substance, with no more wizardry than is required to read and play single melody lines. The vehicle is a lightweight notation I call PKP (for Picturing Keyboard Patterns) for annotating the core flow of harmony in interval terms above the staff. I developed the notation as an adult beginner with no training in music theory after becoming frustrated with the way music notation obscures the keyboard simplicity of harmony. That the notation has substance in spite of this humble origin is indicated by the following opinion of PKP provided by a music theorist specializing in improvisational music (see supplementary pages): “The hook ... , at least in my opinion, is that it's possible to attain a deep understanding of chords (and their constituent intervals) without recourse to Western notation. This has direct consequences for physical patterning, fingerings, etc. Essentially, your method combines the utility of a play-by-ear approach with the depth of a mathematically-informed theory of music.” PKP follows from two observations that anyone can make. One is the piano keyboard supplies only 12 piano keys to play all the notes of an octave that music notation describes in many more than 12 ways by key signatures and accidentals (sharps, flats, naturals). -

The Processing of Pitch and Scale: an ERP Study of Musicians Trained Outside of the Western Musical System

Empirical Musicology Review Vol. 1, No. 4, 2006 The Processing of Pitch and Scale: An ERP Study of Musicians Trained Outside of the Western Musical System LAURA BISCHOFF RENNINGER [1] Shepherd University MICHAEL P. WILSON University of Illinois EMANUEL DONCHIN University of South Florida ABSTRACT: The current study extends the efforts of Bischoff Renninger, Granot and Donchin (2003) to non-Western musical systems and focuses specifically on Event- Related Potential (ERP) responses to scalar deviations within the Javanese pélog scale by groups of musicians trained within the Western and Javanese systems. The principal aim is to ascertain whether results found in previous experiments may be obtained cross- culturally. Participants include five subjects trained in the Western system only (control group) and five subjects trained in both the Western and Javanese systems (experimental group). Tasks include identifying scalar deviations within the Western diatonic scale, identifying scalar deviations within the Javanese pèlog scale, and identifying target letters in a visual control task. ERP and overt behavioral responses are recorded. Results show significant differences between group responses to diatonic and Javanese scale conditions. Interesting results also arise in terms of how tones and intervals in the different scales are conceptualized by subjects in both groups. Control subjects especially tend to assimilate pélog scale intervals to intervals in the Western equal- tempered scale. Submitted 2006 June 21; accepted 2006 June 26. KEYWORDS: music, scale, ERP, event-related potential, tuning, interval, enculturation INTRODUCTION IN human culture, music is as far-reaching a phenomenon as language. And, like language, learning another culture’s music can be both complicated and challenging. -

Harmonic Major – Part I, Blackbird by Adam Coulombe

Harmonic Major – Part I, Blackbird By Adam Coulombe The tonality of harmonic there is an absence of seven triad on the flat sixth degree. G major is a fundamental tonality in primary chords and their scales. harmonic major is spelled : music harmony. There are those Usually, only the G A B C D E♭ F♯ G that have never heard of it, and tonalities of major, melodic minor, My belief is that those that have heard of it but do and harmonic minor are taught and eventually everyone will have the not understand that it is a used when analysing the harmony a opportunity to understand tertian completely tertian and diatonic piece of music moves through. This harmony correctly, and completely, tonality. Tertian harmony is the can create an incorrect analysis of that there are four tonalities, term given to chords spelled with a the harmony in a piece when major, harmonic major, melodic major or minor third interval chords from harmonic major are minor, and harmonic minor. I between each chord tone in root used but not recognized as such. believe this should be a standard position, to start with. Diatonic For example, the sheet music to model for all musicians to study as refers to one note being the center Paul McCartney’s Blackbird has a basis to understand all other of the tonality, called the tonic been consistently printed forms of applied harmony. note, and that the harmony created incorrectly due to this lack of I am interested to know in this tonality relates ‘to the tonic.’ knowledge of the tonality of what other institutions and Why this tonality is largely harmonic major.