A LIGHTWEIGHT NOTATION for PLAYING PIANO for FUN by R.J.A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

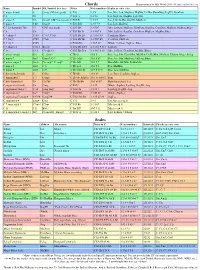

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

Naming a Chord Once You Know the Common Names of the Intervals, the Naming of Chords Is a Little Less Daunting

Naming a Chord Once you know the common names of the intervals, the naming of chords is a little less daunting. Still, there are a few conventions and short-hand terms that many musicians use, that may be confusing at times. A few terms are used throughout the maze of chord names, and it is good to know what they refer to: Major / Minor – a “minor” note is one half step below the “major.” When naming intervals, all but the “perfect” intervals (1,4, 5, 8) are either major or minor. Generally if neither word is used, major is assumed, unless the situation is obvious. However, when used in naming extended chords, the word “minor” usually is reserved to indicate that the third of the triad is flatted. The word “major” is reserved to designate the major seventh interval as opposed to the minor or dominant seventh. It is assumed that the third is major, unless the word “minor” is said, right after the letter name of the chord. Similarly, in a seventh chord, the seventh interval is assumed to be a minor seventh (aka “dominant seventh), unless the word “major” comes right before the word “seventh.” Thus a common “C7” would mean a C major triad with a dominant seventh (CEGBb) While a “Cmaj7” (or CM7) would mean a C major triad with the major seventh interval added (CEGB), And a “Cmin7” (or Cm7) would mean a C minor triad with a dominant seventh interval added (CEbGBb) The dissonant “Cm(M7)” – “C minor major seventh” is fairly uncommon outside of modern jazz: it would mean a C minor triad with the major seventh interval added (CEbGB) Suspended – To suspend a note would mean to raise it up a half step. -

MUSIC THEORY UNIT 5: TRIADS Intervallic Structure of Triads

MUSIC THEORY UNIT 5: TRIADS Intervallic structure of Triads Another name of an interval is a “dyad” (two pitches). If two successive intervals (3 notes) happen simultaneously, we now have what is referred to as a chord or a “triad” (three pitches) Major and Minor Triads A Major triad consists of a M3 and a P5 interval from the root. A minor triad consists of a m3 and a P5 interval from the root. Diminished and Augmented Triads A diminished triad consists of a m3 and a dim 5th interval from the root. An augmented triad consists of a M3 and an Aug 5th interval from the root. The augmented triad has a major third interval and an augmented fifth interval from the root. An augmented triad differs from a major triad because the “5th” interval is a half-step higher than it is in the major triad. The diminished triad differs from minor triad because the “5th” interval is a half-step lower than it is in the minor triad. Recommended process: 1. Memorize your Perfect 5th intervals from most root pitches (ex. A-E, B-F#, C-G, D-A, etc…) 2. Know that a Major 3rd interval is two whole steps from a root pitch If you can identify a M3 and P5 from a root, you will be able to correctly spell your Major Triads. 3. If you need to know a minor triad, adjust the 3rd of the major triad down a half step to make it minor. 4. If you need to know an Augmented triad, adjust the 5th of the chord up a half step from the MAJOR triad. -

Day 17 AP Music Handout, Scale Degress.Mus

Scale Degrees, Chord Quality, & Roman Numeral Analysis There are a total of seven scale degrees in both major and minor scales. Each of these degrees has a name which you are required to memorize tonight. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 & w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic A triad can be built upon each scale degree. w w w w & w w w w w w w w 1. tonicw 2.w supertonic 3.w mediant 4. subdominant 5. dominant 6. submediant 7. leading tone 1. tonic The quality and scale degree of the triads is shown by Roman numerals. Captial numerals are used to indicate major triads with lowercase numerals used to show minor triads. Diminished triads are lowercase with a "degree" ( °) symbol following and augmented triads are capital followed by a "plus" ( +) symbol. Roman numerals written for a major key look as follows: w w w w & w w w w w w w w CM: wI (M) iiw (m) wiii (m) IV (M) V (M) vi (m) vii° (dim) I (M) EVERY MAJOR KEY FOLLOWS THE PATTERN ABOVE FOR ITS ROMAN NUMERALS! Because the seventh scale degree in a natural minor scale is a whole step below tonic instead of a half step, the name is changed to subtonic, rather than leading tone. Leading tone ALWAYS indicates a half step below tonic. Notice the change in the qualities and therefore Roman numerals when in the natural minor scale. -

Practical Music Theory – Book 1 by Pete Ford Table of Contents

Practical Music Theory – Book 1 by Pete Ford Table of Contents Preface xi About This Book Series xii To the Instructor xii Acknowledgements xii Part One Chapter 1: Notation 1 Clefs 1 The Grand Staff 2 Notes 2 Rests 3 Note Names 4 Rhythm 5 Simple Time 6 Dotted Notes in Simple Time 7 Compound Time 8 Subdivision in Compound Time 10 The Phrase Marking, Slur and the Tie 12 The Tie in Simple Time 12 The Tie in Compound Time 13 Repeat Signs, da Capo, and More 14 Assignment 1-1: Name the Notes 19 Assignment 1-2: Simple Time 21 Assignment 1-3: Compound Time 23 Chapter 2: Key Signatures 25 Writing Accidental Signs 25 The Cycle of Fourths 26 Key Signatures with Flats 27 Key Signatures with Sharps 28 Enharmonic Keys 30 Assignment 2-1: Name the Key Signature 33 Assignment 2-2: Key Signatures 35 Table of Contents Chapter 3: Building Scales 37 Writing the Major Scale 38 Introduction to Solfege 39 The Relative Minor Scale 40 The Cycle with Minor Keys Added 41 Writing the Natural Minor Scale 41 Solfege in Minor Keys 42 The Harmonic Minor Scale 44 The Melodic Minor Scale 46 Assignment 3-1: Write the Scales #1 49 Assignment 3-2: Write the Scales #2 51 Chapter 4: Intervals 53 Primary Intervals of the Major Scale 53 Writing Ascending Intervals 55 Writing Descending Intervals 57 Playing Intervals on the Piano 59 Hearing and Singing Intervals 59 Secondary Intervals 60 Writing Descending Secondary Intervals 62 Assignment 4-1: Write the Intervals 65 Assignment 4-2: Secondary Intervals 67 Part Two Chapter 5: Building Chords (SATB) 71 Triads of the Major Scale -

The Sonata, Its Form and Meaning As Exemplified in the Piano Sonatas by Mozart

THE SONATA, ITS FORM AND MEANING AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIANO SONATAS BY MOZART. MOZART. Portrait drawn by Dora Stock when Mozart visited Dresden in 1789. Original now in the possession of the Bibliothek Peters. THE SONATA ITS FORM AND MEANING AS EXEMPLIFIED IN THE PIANO SONATAS BY MOZART A DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS BY F. HELENA MARKS WITH MCSICAL EXAMPLES LONDON WILLIAM REEVES, 83 CHARING CROSS ROAD, W.C.2. Publisher of Works on Music. BROUDE BROS. Music NEW YORK Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the Library of DR. ARTHUR PLETTNER AND ISA MCILWRAITH PLETTNER Crescent, London, S.W.16. Printed by The New Temple Press, Norbury PREFACE. undertaking the present work, the writer's intention originally was IN to offer to the student of musical form an analysis of the whole of Mozart's Pianoforte Sonatas, and to deal with the subject on lines some- what similar to those followed by Dr. Harding in his volume on Beet- hoven. A very little thought, however, convinced her that, though students would doubtless welcome such a book of reference, still, were the scope of the treatise thus limited, its sphere of usefulness would be somewhat circumscribed. " Mozart was gifted with an extraordinary and hitherto unsurpassed instinct for formal perfection, and his highest achievements lie not more in the tunes which have so captivated the world, than in the perfect sym- metry of his best works In his time these formal outlines were fresh enough to bear a great deal of use without losing their sweetness; arid Mozart used them with remarkable regularity."* The author quotes the above as an explanation of certain broad similarities of treatment which are to be found throughout Mozart's sonatas. -

The Misunderstood Eleventh Amendment

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW Founded !"#$ Formerly AMERICAN LAW REGISTER © !"!# University of Pennsylvania Law Review VOL. !"# FEBRUARY $%$! NO. & ARTICLE THE MISUNDERSTOOD ELEVENTH AMENDMENT WILLIAM BAUDE† & STEPHEN E. SACHS†† The Eleventh Amendment might be the most misunderstood amendment to the Constitution. Both its friends and enemies have treated the Amendment’s written † Professor of Law, University of Chicago Law School. †† Colin W. Brown Professor of Law, Duke University School of Law. We are grateful for comments and suggestions from Sam Bray, Tom Colby, Scott Dodson, Jonathan Gienapp, Tara Grove, Julian Davis Mortenson, Caleb Nelson, Jim Pfander, Richard Re, Amanda Schwoerke, Eric Segall, Jonathan Urick, Ingrid Wuerth, and from participants in the Fall Speaker Series of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution, the Hugh & Hazel Darling Foundation Originalism Works-in-Progress Conference at the University of San Diego Law School, and Advanced Topics in Federal Courts at the University of Virginia School of Law. Thanks as well to Brendan Anderson, Kurtis Michael, and Scotty Schenck for research assistance, and to the SNR Denton Fund and Alumni Faculty Fund at Chicago for research support. (!"#) !"# University of Pennsylvania Law Review [Vol. "!$: !#$ text, and the unwritten doctrines of state sovereign immunity, as one and the same— reading broad principles into its precise words, or treating the written Amendment as merely illustrative of unwritten doctrines. The result is a bewildering forest of case law, which takes neither the words nor the doctrines seriously. The truth is simpler: the Eleventh Amendment means what it says. It strips the federal government of judicial power over suits against states, in law or equity, brought by diverse plaintiffs. -

The Devil's Interval by Jerry Tachoir

Sound Enhanced Hear the music example in the Members Only section of the PAS Web site at www.pas.org The Devil’s Interval BY JERRY TACHOIR he natural progression from consonance to dissonance and ii7 chords. In other words, Dm7 to G7 can now be A-flat m7 to resolution helps make music interesting and satisfying. G7, and both can resolve to either a C or a G-flat. Using the TMusic would be extremely bland without the use of disso- other dominant chord, D-flat (with the basic ii7 to V7 of A-flat nance. Imagine a world of parallel thirds and sixths and no dis- m7 to D-flat 7), we can substitute the other relative ii7 chord, sonance/resolution. creating the progression Dm7 to D-flat 7 which, again, can re- The prime interval requiring resolution is the tritone—an solve to either a C or a G-flat. augmented 4th or diminished 5th. Known in the early church Here are all the possibilities (Note: enharmonic spellings as the “Devil’s interval,” tritones were actually prohibited in of- were used to simplify the spelling of some chords—e.g., B in- ficial church music. Imagine Bach’s struggle to take music stead of C-flat): through its normal progression of tonic, subdominant, domi- nant, and back to tonic without the use of this interval. Dm7 G7 C Dm7 G7 Gb The tritone is the characteristic interval of all dominant bw chords, created by the “guide tones,” or the 3rd and 7th. The 4 ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ tritone interval can be resolved in two types of contrary motion: &4˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ bbw one in which both notes move in by half steps, and one in which ˙ ˙ w ˙ ˙ b w both notes move out by half steps. -

Major and Minor Scales Half and Whole Steps

Dr. Barbara Murphy University of Tennessee School of Music MAJOR AND MINOR SCALES HALF AND WHOLE STEPS: half-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that are adjacent on the piano keyboard whole-step - two keys (and therefore notes/pitches) that have another key in between chromatic half-step -- a half step written as two of the same note with different accidentals (e.g., F-F#) diatonic half-step -- a half step that uses two different note names (e.g., F#-G) chromatic half step diatonic half step SCALES: A scale is a stepwise arrangement of notes/pitches contained within an octave. Major and minor scales contain seven notes or scale degrees. A scale degree is designated by an Arabic numeral with a cap (^) which indicate the position of the note within the scale. Each scale degree has a name and solfege syllable: SCALE DEGREE NAME SOLFEGE 1 tonic do 2 supertonic re 3 mediant mi 4 subdominant fa 5 dominant sol 6 submediant la 7 leading tone ti MAJOR SCALES: A major scale is a scale that has half steps (H) between scale degrees 3-4 and 7-8 and whole steps between all other pairs of notes. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 W W H W W W H TETRACHORDS: A tetrachord is a group of four notes in a scale. There are two tetrachords in the major scale, each with the same order half- and whole-steps (W-W-H). Therefore, a tetrachord consisting of W-W-H can be the top tetrachord or the bottom tetrachord of a major scale. -

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth Chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen Chords Sometimes Referred to As Chords with 'Extensions', I.E

Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteenth chords Ninth, Eleventh and Thirteen chords sometimes referred to as chords with 'extensions', i.e. extending the seventh chord to include tones that are stacking the interval of a third above the basic chord tones. These chords with upper extensions occur mostly on the V chord. The ninth chord is sometimes viewed as superimposing the vii7 chord on top of the V7 chord. The combination of the two chord creates a ninth chord. In major keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a whole step above the root (plus octaves) w w w w w & c w w w C major: V7 vii7 V9 G7 Bm7b5 G9 ? c ∑ ∑ ∑ In the minor keys the ninth of the dominant ninth chord is a half step above the root (plus octaves). In chord symbols it is referred to as a b9, i.e. E7b9. The 'flat' terminology is use to indicate that the ninth is lowered compared to the major key version of the dominant ninth chord. Note that in many keys, the ninth is not literally a flatted note but might be a natural. 4 w w w & #w #w #w A minor: V7 vii7 V9 E7 G#dim7 E7b9 ? ∑ ∑ ∑ The dominant ninth usually resolves to I and the ninth often resolves down in parallel motion with the seventh of the chord. 7 ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ & ˙ ˙ #˙ ˙ C major: V9 I A minor: V9 i G9 C E7b9 Am ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ? ˙ ˙ The dominant ninth chord is often used in a II-V-I chord progression where the II chord˙ and the I chord are both seventh chords and the V chord is a incomplete ninth with the fifth omitted. -

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context

When the Leading Tone Doesn't Lead: Musical Qualia in Context Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Claire Arthur, B.Mus., M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: David Huron, Advisor David Clampitt Anna Gawboy c Copyright by Claire Arthur 2016 Abstract An empirical investigation is made of musical qualia in context. Specifically, scale-degree qualia are evaluated in relation to a local harmonic context, and rhythm qualia are evaluated in relation to a metrical context. After reviewing some of the philosophical background on qualia, and briefly reviewing some theories of musical qualia, three studies are presented. The first builds on Huron's (2006) theory of statistical or implicit learning and melodic probability as significant contributors to musical qualia. Prior statistical models of melodic expectation have focused on the distribution of pitches in melodies, or on their first-order likelihoods as predictors of melodic continuation. Since most Western music is non-monophonic, this first study investigates whether melodic probabilities are altered when the underlying harmonic accompaniment is taken into consideration. This project was carried out by building and analyzing a corpus of classical music containing harmonic analyses. Analysis of the data found that harmony was a significant predictor of scale-degree continuation. In addition, two experiments were carried out to test the perceptual effects of context on musical qualia. In the first experiment participants rated the perceived qualia of individual scale-degrees following various common four-chord progressions that each ended with a different harmony. -

Boris's Bells, by Way of Schubert and Others

Boris's Bells, By Way of Schubert and Others Mark DeVoto We define "bell chords" as different dominant-seventh chords whose roots are separated by multiples of interval 3, the minor third. The sobriquet derives from the most famous such pair of harmonies, the alternating D7 and AI? that constitute the entire harmonic substance of the first thirty-eight measures of scene 2 of the Prologue in Musorgsky's opera Boris Godunov (1874) (example O. Example 1: Paradigm of the Boris Godunov bell succession: AJ,7-D7. A~7 D7 '~~&gl n'IO D>: y 7 G: y7 The Boris bell chords are an early milestone in the history of nonfunctional harmony; yet the two harmonies, considered individually, are ofcourse abso lutely functional in classical contexts. This essay traces some ofthe historical antecedents of the bell chords as well as their developing descendants. Dominant Harmony The dominant-seventh chord is rightly recognized as the most unambiguous of the essential tonal resources in classical harmonic progression, and the V7-1 progression is the strongest means of moving harmony forward in immediate musical time. To put it another way, the expectation of tonic harmony to follow a dominant-seventh sonority is a principal component of forehearing; we assume, in our ordinary and long-tested experience oftonal music, that the tonic function will follow the dominant-seventh function and be fortified by it. So familiar is this everyday phenomenon that it hardly needs to be stated; we need mention it here only to assert the contrary case, namely, that the dominant-seventh function followed by something else introduces the element of the unexpected.