Joint Statutory Committee on the Independent Commission Against Corruption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Annual Report 2019-2020

Leading � rec�very Annual Report 2019–2020 TARONGA ANNUAL REPORT 2019–2020 A SHARED FUTURE � WILDLIFE AND PE�PLE At Taronga we believe that together we can find a better and more sustainable way for wildlife and people to share this planet. Taronga recognises that the planet’s biodiversity and ecosystems are the life support systems for our own species' health and prosperity. At no time in history has this been more evident, with drought, bushfires, climate change, global pandemics, habitat destruction, ocean acidification and many other crises threatening natural systems and our own future. Whilst we cannot tackle these challenges alone, Taronga is acting now and working to save species, sustain robust ecosystems, provide experiences and create learning opportunities so that we act together. We believe that all of us have a responsibility to protect the world’s precious wildlife, not just for us in our lifetimes, but for generations into the future. Our Zoos create experiences that delight and inspire lasting connections between people and wildlife. We aim to create conservation advocates that value wildlife, speak up for nature and take action to help create a future where both people and wildlife thrive. Our conservation breeding programs for threatened and priority wildlife help a myriad of species, with our program for 11 Legacy Species representing an increased commitment to six Australian and five Sumatran species at risk of extinction. The Koala was added as an 11th Legacy Species in 2019, to reflect increasing threats to its survival. In the last 12 months alone, Taronga partnered with 28 organisations working on the front line of conservation across 17 countries. -

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Wednesday, 23 September 2020 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Wednesday, 23 September 2020 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 10:00. The PRESIDENT read the prayers. Motions MANUFACTURING PROJECTS UPDATE The Hon. PETER PRIMROSE (10:01:47): I move: (1) That this House notes the resolution of the House of Wednesday 16 September 2020 in which this House recognised the critical importance of manufacturing jobs in Western Sydney and called on the Government to stop sending manufacturing jobs overseas. (2) That this House calls on the Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council to report to the House on the following matters: (a) the specific major manufacturing projects since 2011 for both Western Sydney and New South Wales, that the Government or any of its agencies procured from overseas; (b) the estimated total number of jobs for each major manufacturing project since 2011 that have been exported from New South Wales as a consequence of the decision to undertake procurement from overseas; (c) the specific manufacturing projects over the period of the forward estimates that the Government or any of its agencies propose to procure from overseas; (d) any additional legislative and regulatory frameworks proposed to be introduced by the Government in order to implement the resolution of the House that it stop sending manufacturing jobs overseas; and (e) any immediate and long term additional investments proposed by the Government in TAFE; including how it will expand training, education and employment pathways especially for young people. Motion agreed to. Committees LEGISLATION REVIEW COMMITTEE Membership Ms ABIGAIL BOYD: I move: That under section 5 of the Legislation Review Act 1987, Mr David Shoebridge be discharged from the Legislation Review Committee and Ms Abigail Boyd be appointed as a member of the committee. -

2020 Review of the Annual Reports of Oversight Bodies

Parliament of New South Wales Committee on the Ombudsman, the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission and the Crime Commission 1/57 – August 2020 2020 Review of the Annual Reports of oversighted bodies New South Wales Parliamentary Library cataloguing-in-publication data: New South Wales. Parliament. Committee on the Ombudsman, the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission and the Crime Commission. 2020 Review of the annual reports of oversighted bodies / Committee on the Ombudsman, the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission and the Crime Commission, Parliament NSW. [Sydney, N.S.W.] : the Committee, 2020. – 1 online resource (47 pages) (Report ; no. 1/57). Chair: Dugald Saunders, MP. ISBN: 9781921012921 1. Administrative agencies—New South Wales—Auditing. 2. Corporation reports—New South Wales. 3. Corruption investigation—New South Wales. I. Title II. Saunders, Dugald. III. Series: New South Wales. Parliament. Committee on the Ombudsman, the Law Enforcement Conduct Commission and the Crime Commission. Report ; no. 1/57 352.88 (DDC) The motto of the coat of arms for the state of New South Wales is “Orta recens quam pura nites”. It is written in Latin and means “newly risen, how brightly you shine”. 2020 review of oversighted bodies Contents Membership ____________________________________________________________ iii Chair’s foreword __________________________________________________________iv Findings and recommendations ______________________________________________ v Chapter One – Law Enforcement Conduct Commission and Inspector of the Law Enforcement -

Annual Report 2020 CONTENTS Thank You! 4

Annual Report 2020 CONTENTS Thank You! 4. Report from the President Tresillian acknowledges the generosity of the many companies and individuals who have provided financial or 7. Report from the CEO in-kind sponsorship to our services throughout the year. 12. Tresillian Centres & Services We especially thank our major sponsors, Johnson & Johnson, who have generously supported Tresillian 13. Social Impact for over 27 years, contributing to services such as the 14. COVID-19 Snapshot Parent’s Help Line and Tresillian Live Advice. We also thank Allianz, Reckitt Benckiser and the many other 15. Digital Services companies whose support enables parents to receive 16. How Tresillian Supports Families timely, practical advice from Tresillian. 18. Report from Clinical Services 22. Report on Governance, Risk & Performance 24. Report from the Tresillian Professor 25. Tresillian’s History Incorporated by an Act of 26. Executive Team Parliament 27. Organisation Structure The Royal Society for the Welfare of Mothers and 28. The Tresillian Board Babies was incorporated by an Act of Parliament in 30. Financial Report New South Wales, Australia in 1919. 31. Financial Performance & Position (Tresillian’s official name is The Royal Society for the Welfare of Mothers & Babies). 32. Our People Patron We are proud to have Queen Elizabeth II as our Patron. 2020 Tresillian Annual General Meeting The 2019/2020 Tresillian Annual Report was presented at the 2020 Tresillian Annual General Meeting at 3pm, Tresillian acknowledges the Traditional Thursday 26th November 2020, at the Royal Automobile Club, 89 Macquarie Street, Sydney. Owners of the lands on which live and work and pays its respects to their Elders past, present and emerging. -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 4 August 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Tuesday, 4 August 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 12:00. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. [Notices of motions given.] Bills GAS LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (MEDICAL GAS SYSTEMS) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Kevin Anderson, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr KEVIN ANDERSON (Tamworth—Minister for Better Regulation and Innovation) (12:16:12): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. I am proud to introduce the Gas Legislation Amendment (Medical Gas Systems) Bill 2020. The bill delivers on the New South Wales Government's promise to introduce a robust and effective licensing regulatory system for persons who carry out medical gas work. As I said on 18 June on behalf of the Government in opposing the Hon. Mark Buttigieg's private member's bill, nobody wants to see a tragedy repeated like the one we saw at Bankstown-Lidcombe Hospital. As I undertook then, the Government has taken the steps necessary to provide a strong, robust licensing framework for those persons installing and working on medical gases in New South Wales. To the families of John Ghanem and Amelia Khan, on behalf of the Government I repeat my commitment that we are taking action to ensure no other families will have to endure as they have. The bill forms a key part of the Government's response to licensed work for medical gases that are supplied in medical facilities in New South Wales. -

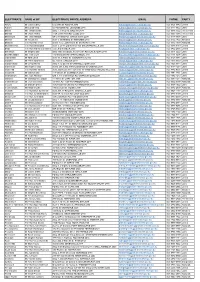

NSW Govt Lower House Contact List with Hyperlinks Sep 2019

ELECTORATE NAME of MP ELECTORATE OFFICE ADDRESS EMAIL PHONE PARTY Albury Mr Justin Clancy 612 Dean St ALBURY 2640 [email protected] (02) 6021 3042 Liberal Auburn Ms Lynda Voltz 92 Parramatta Rd LIDCOMBE 2141 [email protected] (02) 9737 8822 Labor Ballina Ms Tamara Smith Shop 1, 7 Moon St BALLINA 2478 [email protected] (02) 6686 7522 The Greens Balmain Mr Jamie Parker 112A Glebe Point Rd GLEBE 2037 [email protected] (02) 9660 7586 The Greens Bankstown Ms Tania Mihailuk 9A Greenfield Pde BANKSTOWN 2200 [email protected] (02) 9708 3838 Labor Barwon Mr Roy Butler Suite 1, 60 Maitland St NARRABRI 2390 [email protected] (02) 6792 1422 Shooters Bathurst The Hon Paul Toole Suites 1 & 2, 229 Howick St BATHURST 2795 [email protected] (02) 6332 1300 Nationals Baulkham Hills The Hon David Elliott Suite 1, 25-33 Old Northern Rd BAULKHAM HILLS 2153 [email protected] (02) 9686 3110 Liberal Bega The Hon Andrew Constance 122 Carp St BEGA 2550 [email protected] (02) 6492 2056 Liberal Blacktown Mr Stephen Bali Shop 3063 Westpoint, Flushcombe Rd BLACKTOWN 2148 [email protected] (02) 9671 5222 Labor Blue Mountains Ms Trish Doyle 132 Macquarie Rd SPRINGWOOD 2777 [email protected] (02) 4751 3298 Labor Cabramatta Mr Nick Lalich Suite 10, 5 Arthur St CABRAMATTA 2166 [email protected] (02) 9724 3381 Labor Camden Mr Peter Sidgreaves 66 John St CAMDEN 2570 [email protected] (02) 4655 3333 Liberal -

3021 Business Paper

3021 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2019-20-21 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT BUSINESS PAPER No. 86 TUESDAY 16 MARCH 2021 GOVERNMENT BUSINESS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Rob Stokes, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 24 October 2019—Mr Paul Scully). 2 Firearms and Weapons Legislation Amendment (Criminal Use) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr David Elliott, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 26 February 2020— Ms Steph Cooke). 3 COVID-19 Legislation Amendment (Stronger Communities and Health) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Mark Speakman, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 18 February 2021—Mr Paul Lynch). 4 Budget Estimates and related papers 2020-2021; resumption of the interrupted debate, on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this House take note of the Budget Estimates and related papers 2020-21". (Moved 19 November 2020—Mr Guy Zangari speaking, 11 minutes remaining). 5 Reference to the Independent Commission Against Corruption; consideration of the message from the Legislative Council dated 18 September 2019. (Mr Andrew Constance). 3022 BUSINESS PAPER Tuesday 16 March 2021 BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE—PETITIONS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Petition—from certain citizens requesting the Legislative Assembly support cancellation plans for a bridge at River Street, Dubbo, and instead raise Troy Bridge above the flood plain to create a Newell Highway bypass. (Mr David Harris). -

3119 Business Paper

3119 PROOF LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY 2019-20-21 FIRST SESSION OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH PARLIAMENT BUSINESS PAPER No. 89 TUESDAY 23 MARCH 2021 GOVERNMENT BUSINESS ORDERS OF THE DAY— 1 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Rob Stokes, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 24 October 2019—Mr Paul Scully). 2 Firearms and Weapons Legislation Amendment (Criminal Use) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr David Elliott, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 26 February 2020— Ms Steph Cooke). 3 COVID-19 Recovery Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021—Ms Janelle Saffin). 4 Mutual Recognition (New South Wales) Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Dominic Perrottet, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021— Ms Sophie Cotsis). 5 Real Property Amendment (Certificates of Title) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Victor Dominello, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021—Ms Sophie Cotsis). 6 Local Government Amendment Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mrs Shelley Hancock, "That this bill be now read a second time". (Introduced 17 March 2021—Mr Greg Warren). 7 Civil Liability Amendment (Child Abuse) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate on the motion of Mr Mark Speakman, "That this bill be now read a second time". -

BUSINESS PROGRAM Fifty-Seventh Parliament, First Session Legislative Assembly

BUSINESS PROGRAM Fifty-Seventh Parliament, First Session Legislative Assembly Thursday 4 June 2020 At 9.30 am Giving of Notices of Motions (General Notices) (for a period of up to 15 minutes) GOVERNMENT BUSINESS (for a period of up to 30 minutes) Orders of the Day No. 1 Environmental Planning and Assessment Amendment (Territorial Limits) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Mr Rob Stokes—Mr Paul Scully*). No. 2 Firearms and Weapons Legislation Amendment (Criminal Use) Bill; resumption of the adjourned debate (Mr David Elliott—Ms Steph Cooke*). No. 3 Budget Estimates and related papers 2019-2020; resumption of the interrupted debate (Mr Dominic Perrottet—Ms Janelle Saffin speaking (7 minutes remaining)). * denotes Member who adjourned the debate GENERAL BUSINESS Notices of Motions (for Bills) (for a period of up to 20 minutes) No.2 Transport Administration Amendment (International Students Travel Concession) Bill introduction of the bill (Ms Jenny Leong) No. 3 Water Management Amendment (Water Rights Transparency) Bill (No. 2); introduction of the bill (Mrs Helen Dalton) Notices of Motions (General Notices) (until 1.15pm) No.1034 Kim Goldsmith – Dubbo Arts (Mr Dugald Saunders) No.1035 Ausgrid Linesmen – Hunter Region (Ms Sonia Hornery) No.1036 Newman Senior Technical College – Pink Stumps Day (Mrs Leslie Williams) No.1037 Local Government Councillors – Freedom of Speech (Mrs Helen Dalton) No.1038 Orange Courthouse (Ms Steph Cooke) No. 1039 National Parks Budget (Ms Kate Washington) No.1040 Dunlea Centre – 80th Anniversary (Mr Lee -

Up to 10,000 People Rallied to Stop Abortion Bill in New South Wales

RIGHT TO LIFE NEWS AUGUST SEPTEMBER 2019 The NSW Abortion Debate 2019 Up to 10,000 people rallied to stop Australia has recently been reminded of its disgraceful record on government- abortion bill in New South Wales funded abortions with the NSW parliament engaged in a fiery debate over the total legislation of abortion until birth! To our utter disgrace this is now the Margaret Tighe situation in Victoria, Tasmania and Queensland with South Australia poised to follow suit after the usual “government inquiry”. Amazingly Sydney has been rocked by large anti-abortion protests in its streets and outside its parliament. Clearly the churches have played a major role in turning out the protestors. The sad reality is that abortions have been widely available in New South Wales for many years – late abortion included. An abortion clinic even operated opposite the NSW Parliament building in Macquarie Street. Many years ago, on enquiring at a Written by Jane Landon. Jane is a supporter of Right to Life well-known Sydney abortuary. I was told I could have an abortion Australia who was very active during our Federal Election up till 22 weeks! So – what’s new? campaign in Bennelong Electorate. Picture by Aleshia Fewster. Sadly, passage of this bill in Parliament will serve to legitimise the killing of the unborn – from 22 weeks and after if two doctors and Pro-life protestors gathered for a vigil at Martin Place, Sydney on Tues the woman agree. 20 August 2019 at 6pm. The rally was to oppose the abortion bill being And – it will lead to the killing of more and more children in the debated in Parliament House. -

Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1

Thursday, 22 October 2020 Legislative Assembly- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Thursday, 22 October 2020 The Speaker (The Hon. Jonathan Richard O'Dea) took the chair at 09:30. The Speaker read the prayer and acknowledgement of country. Announcements THOUGHT LEADERSHIP BREAKFAST The SPEAKER: I inform the House that we had two outstanding leaders of Indigenous heritage at our Thought Leadership breakfast this morning. I thank all those members who attended that event. In particular I thank our guest speakers: Tanya Denning-Allman, the director of Indigenous content at SBS, and Benson Saulo, the incoming Consul-General to the United States, based in Houston. I thank both of them and note we will have another event in November. [Notices of motions given.] Bills STRONGER COMMUNITIES LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (DOMESTIC VIOLENCE) BILL 2020 First Reading Bill introduced on motion by Mr Mark Speakman, read a first time and printed. Second Reading Speech Mr MARK SPEAKMAN (Cronulla—Attorney General, and Minister for the Prevention of Domestic Violence) (09:46:44): I move: That this bill be now read a second time. The Stronger Communities Legislation Amendment (Domestic Violence) Bill 2020 introduces amendments to support procedural improvements and to close gaps in the law that have become apparent. Courts can be a daunting place for victims of domestic and family violence. The processes can be overwhelming. Domestic violence is a complex crime like no other because of the intimate relationships between perpetrators and victims. Those close personal connections intertwine complainants and defendants in ways that maintain a callous grip on victims. This grip can silence reports of abuse, delay reports when victims are brave enough to come forward, and intimidate victims to discontinue cooperating with prosecutions. -

Project Update Week Ending 13 November 2020

Project Update Week ending 13 November 2020 Strandline appoints Contract Power as preferred contractor to build Coburn’s power fuelled generation with state-of-the-art solar facilities and battery storage technology. 4 November The proposed power solution enables HIGHLIGHTS Strandline to capture energy supply cost • Strandline appoints Contract Power as savings relative to the Definitive Feasibility preferred contractor to build, own and Study (DFS) published in June 2020. operate a 32MW hybrid gas and renewable energy solution for the Coburn mineral sands Contract Power, a wholly-owned subsidiary of project in WA Pacific Energy Ltd, specialises in turn-key • The proposed power solution enables design, installation and operation of energy Strandline to capture energy supply cost assets and has a strong track record of savings relative to the Definitive Feasibility delivery in the mining sector of WA. Study (DFS) published in June 2020 • Innovative low-cost, low-emission solution Coburn’s power station will be located near integrating gas-fuelled power generation with the mineral separation plant (MSP). The solar renewable energy and battery storage power station is designed suitable for a technology maximum demand capacity of 16 MW and • The parties have now commenced average consumed power of ~10 MW. preparation of final contract documentation to the satisfaction of Strandline and Coburn’s Natural gas will be supplied by others under lender group an industry standard long-term LNG supply • The scope represents a major development agreement and trucked to an on-site storage package and is one of Strandline’s conditions and re-vapourisation facility supplied by precedent to finalise project funding Contract Power.