Downloaded from Brill.Com09/28/2021 06:32:40AM Via Free Access 332 CHAPTER 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Systems at Yasileh

ARAM, 23 (2011) 619-644. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.23.0.2959676 WATER SYSTEMS AT YASILEH Prof. ZEIDOUN AL-MUHEISEN* (Yarmouk University) Yasileh is located 9 km east of Irbid and 5 km west of ar-Ramtha, in north- ern Jordan. The site of Yasileh has an important geographical location since the area was a crossroad sfor the ancient trading routes between Southern Syria, Jordan and Palestine, in addition to the fact that the land in the sur- rounding area is very fertile and very well suited to agriculture. The Wadi ash-Shallalih area, including the site of Yasileh, a natural basin in which to collect rainwater where the annual rainfall for the Yasileh area has been esti- mated at between 400-500 mm. A sufficient supply of water was also ensured by cisterns cut into the rocky sides of Wadi Yasileh, as well as a spring located 1 km to the north of the site. Yasileh has a variety of water sources, storage and delivery systems including springs, reservoirs, wells, dams, tunnels and canals. Since 1988, ten campaigns have been carried out by the Institute of Archeology and Anthropology at Yarmouk University. Based on the results of the archaeological activities in the site headed by the author, this article will shed light on the water systems at Yasileh. INTRODUCTION The Yasileh site is located in Wadi ash-Shallalih, which represents the lower reaches of Wadi Warran (Schumacher 1890, 108). Wadi ash-Shallalih runs through the area between Hauran and ‘Ajlun and is fed by tributaries arising in the ‘Ajlun mountains; running west of the village of Suf, it continues north- ward to reach the area of ar-Ramtha, where it is known as Wadi Warran. -

Jeffrey Eli Pearson

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dx9g1rj Author Pearson, Jeffrey Eli Publication Date 2011 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture By Jeffrey Eli Pearson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Erich Gruen, Chair Chris Hallett Andrew Stewart Benjamin Porter Spring 2011 Abstract Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture by Jeffrey Eli Pearson Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Erich Gruen, Chair The Nabataeans, best known today for the spectacular remains of their capital at Petra in southern Jordan, continue to defy easy characterization. Since they lack a surviving narrative history of their own, in approaching the Nabataeans one necessarily relies heavily upon the commentaries of outside observers, such as the Greeks, Romans, and Jews, as well as upon comparisons of Nabataean material culture with Classical and Near Eastern models. These approaches have elucidated much about this -

Tourism Impacts in the Site of Umm Qais: an Overview

Journal of Tourism and Hospitality Management December 2018, Vol. 6, No. 2, pp. 140-148 ISSN 2372-5125 (Print) 2372-5133 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jns.v6n2a12 URL: https://doi.org/10.15640/jns.v6n2a12 Tourism Impacts in the Site of Umm Qais: An Overview Mairna H. Mustafa1, Dana H. Hijjawi2 and Fadi Bala'awi3 Abstract This paper aims at shedding the light on the different impacts of tourism development in the site of Umm Qais (Gadara) in Jordan. Despite the economic benefits gained by tourism, deterioration has been witnessed in this site due to damage of archaeological features as well as the displacement of the local community. Implications were suggested to achieve a more sustainable tourism development in the site. Keywords: Umm Qais (Gadara), Tourism impacts, Sustainable development, Local community of Umm Qais. Introduction The Site of Umm Qais (the Greco-Roman Decapolis town of Gadara) is 120 Km north of Amman, and 30 Km northwest of Irbid (both located in Jordan). The site is 518 meters above sea level and is over looking both Lake Tiberias and the Golan Heights, which creates a great point to watch nearby lands across the borders (Teller, 2006) (Map 1). The city was mentioned in the New Testament as χωρά των͂ Γαδαρηνων,͂ (chorā̇ ton̄̇ Gadarenō n)̄̇ or “country of the Gadarenes” (Matthew 8:28), it's the place where Jesus casted out the devil from two men into a herd of pigs (Matthew 8: 28-34), mentioned as well in the parallel passages as (Mark 5:1; Luke 8:26, Luke 8:37): χωρά των͂ Γερασηνων,͂ chorā̇ ton̄̇ Gerasenō n̄̇ “country of the Gerasenes.” (Bible Hub Website: http://biblehub.com/commentaries/matthew/8-28.htm). -

A Comparative Study for the Traditional and Modern Houses in Terms of Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption in Umm Qais City, Jordan

Journal of Ecological Engineering Received: 2018.12.17 Revised: 2019.02.18 Volume 20, Issue 5, May 2019, pages 14–22 Accepted: 2019.03.15 Available online: 2019.04.01 https://doi.org/10.12911/22998993/105324 A Comparative Study for the Traditional and Modern Houses in Terms of Thermal Comfort and Energy Consumption in Umm Qais city, Jordan Hussain H. Alzoubi1*, Amal Th. Almalkawi1 1 College of Architecture and Design, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid 22110, Jordan * Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research presents a comparison study between the vernacular architecture represented by the heritage houses (Fallahy Houses) and the typical contemporary houses in Umm Qais city in the northern part of Jordan, in terms of thermal performance. It analyzes the parameters of the heritage houses to explore the impact on the human thermal comfort and energy consumption compared with the typical modern houses. The study investigates the performance of the vernacular houses and how they respond to the physical and climatic conditions. It also shows how these houses depend on passive design to control solar gains, and decrease heating and cooling loads keeping a good level of thermal comfort inside. The study compares these vernacular houses with the traditional contemporary house in Umm Qais. The selected samples from each type of houses were taken to evaluate the impact of the vernacular principles of design, building construction and materials on the thermal performance and the thermal comfort inside the houses. Computer simulation, accompanied with measuring tools and thermal cameras, was used for thermal analysis in the selected houses. -

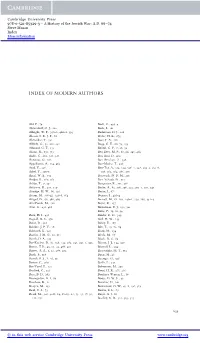

Index of Modern Authors

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-85329-3 - A History of the Jewish War: A.D. 66–74 Steve Mason Index More information INDEX OF MODERN AUTHORS Ahl, F., 74 Beck, C., 493–4 Ahrensdorf, O. J., 221 Beck, I., 101 Albright, W. F., 396–8, 400–1, 593 Bederman, D. J., 220 Alcock, S. E., J. F., 60 Beebe, H. K., 274 Alexandre, Y., 341 Beer, F. A., 218 Alföldy, G., 35, 216, 241 Begg, C. T., 60, 74, 133 Allmand, C. T., 171 Bellori, G. P., 8, 26, 30 Alston, R., 139, 313 Ben Zeev, M. P., 68, 90, 248, 460 Ando, C., 260, 326, 328 Ben-Ami, D., 460 Antonius, G., 262 Ben-Avraham, Z., 398 Appelbaum, A., 154, 462 Ben-Moshe, T., 336 Arad, Y., 538 Ben-Tor, A., 514, 524, 526–7, 548, 550–3, 555–6, Arbel, Y., 350–1 558, 562, 564, 566, 571 Arnal, W. E., 339 Bentwich, N. D. M., 201 Arubas, B., 560, 565 Ben-Yehuda, N., 514 Ashby, T., 7, 39 Bergmeier, R., 131, 458 Atkinson, K., 279, 570 Berlin, A., 65, 136, 206, 225, 230–1, 339, 349 Attridge, H. W., 60, 339 Berlin, I., 67 Aviam, M., 338–41, 345–8, 364 Bernays, J., 491–4 Avigad, N., 68, 466, 469 Bernett, M., 61, 203, 240–1, 259, 266, 342–3 Avi-Yonah, M., 526 Beyer, K., 157 Avni, G., 458, 466 Bickerman, E. J., 232, 301 Bilde, P., 19, 60, 94 Bach, H. I., 491 Binder, D. D., 349 Bagnall, R. S., 470 Bird, H. W., 244 Bahat, D., 468 Birley, E., 167 Balsdon, J. -

My Voice Is My Weapon: Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics Of

MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON MY VOICE IS MY WEAPON Music, Nationalism, and the Poetics of Palestinian Resistance David A. McDonald Duke University Press ✹ Durham and London ✹ 2013 © 2013 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ♾ Cover by Heather Hensley. Interior by Courtney Leigh Baker Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data McDonald, David A., 1976– My voice is my weapon : music, nationalism, and the poetics of Palestinian resistance / David A. McDonald. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5468-0 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5479-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Palestinian Arabs—Music—History and criticism. 2. Music—Political aspects—Israel. 3. Music—Political aspects—Gaza Strip. 4. Music—Political aspects—West Bank. i. Title. ml3754.5.m33 2013 780.89′9274—dc23 2013012813 For Seamus Patrick McDonald Illustrations viii Note on Transliterations xi Note on Accessing Performance Videos xiii Acknowledgments xvii introduction ✹ 1 chapter 1. Nationalism, Belonging, and the Performativity of Resistance ✹ 17 chapter 2. Poets, Singers, and Songs ✹ 34 Voices in the Resistance Movement (1917–1967) chapter 3. Al- Naksa and the Emergence of Political Song (1967–1987) ✹ 78 chapter 4. The First Intifada and the Generation of Stones (1987–2000) ✹ 116 chapter 5. Revivals and New Arrivals ✹ 144 The al- Aqsa Intifada (2000–2010) CONTENTS chapter 6. “My Songs Can Reach the Whole Nation” ✹ 163 Baladna and Protest Song in Jordan chapter 7. Imprisonment and Exile ✹ 199 Negotiating Power and Resistance in Palestinian Protest Song chapter 8. -

Jeffrey Eli Pearson

Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture By Jeffrey Eli Pearson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Erich Gruen, Chair Chris Hallett Andrew Stewart Benjamin Porter Spring 2011 Abstract Contextualizing the Nabataeans: A Critical Reassessment of their History and Material Culture by Jeffrey Eli Pearson Doctor of Philosophy in Ancient History and Mediterranean Archaeology University of California, Berkeley Erich Gruen, Chair The Nabataeans, best known today for the spectacular remains of their capital at Petra in southern Jordan, continue to defy easy characterization. Since they lack a surviving narrative history of their own, in approaching the Nabataeans one necessarily relies heavily upon the commentaries of outside observers, such as the Greeks, Romans, and Jews, as well as upon comparisons of Nabataean material culture with Classical and Near Eastern models. These approaches have elucidated much about this enigmatic civilization but have not always fully succeeded in locating specifically Nabataean motivations and perspectives within and behind the sources. To address this lacuna, my dissertation provides a critical re-reading and analysis of the ancient evidence, including literary, documentary, numismatic, epigraphic, art historical, and archaeological material, in order to explore the Nabataeans’ reaction to, effect upon, and engagement with, historical events and cultural movements during the period from 312 BCE, when the Nabataeans first appear in the historical record in the wake of the conquests of Alexander the Great, to the annexation of their territory by the Romans in 106 CE. -

Occident & Orient

OCCIDENT & ORIENT NecosLeCfen of the Genman Pnotestant Institute of. AachaeoLogy in Amman THE GERMAN PROTESTANT INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY IN AMMAN (DEI) News and Changes This is the sixth volume of our News Goethe-Institute, Amman, the Vorder- Vol. 6, No. 1&2, September 2001 letter Occident &. Orient, but the first asiatisches Museum, Berlin, the Depart CONTENTS volume under a new editorship. As ment of Antiquities of Jordan, Amman, most of our valued readers already and Yarmouk University, Irbid. • Late Roman Belt Buckles 2 know, Dr. Hans-Dieter Bienert left the The annual "Lehrkurs" (a group of institute and Jordan at the end of March • Qanawat 3 scholars holding a travel scholarship 2001. He was succeeded by Dr. Ro from the DEI) spent three weeks in Jor • Words of Appreciation to land Lamprichs, who took office in April dan. They were guided to many ar Dr. Hans-Dieter Bienert 6 and was introduced by the church on chaeological sites by the director of the • Welcome to Dr. Roland Lamprichs 7 September, 16th 2001. DEI-Amman and enjoyed the assistance • Fellows in residence 8 The institute's varied activities since and support of several organizations, • Farewell to Mr. Achilles 9 then have included, for example, lo authorities and institutes within Jordan. • Resafa (Syria) 9 gistical support for several visiting scho A further, very important event in • Digital terrain models examples 12 lars and excavation teams working in recent months was the participation of • Celebrating the Amman Institute 13 Tell Zera" a and Umm Qais, among the institute in the Eighth International • The Jordan Valley Village Project 1 5 others. -

THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM of JORDAN Columbus Travel Pre- Holy Land Adventure Petra, Jerash, Amman, Madaba, Karak, & Mt

THE HASHEMITE KINGDOM OF JORDAN Columbus Travel Pre- Holy Land Adventure Petra, Jerash, Amman, Madaba, Karak, & Mt. Nebo March 12-17, 2022 Our exciting and unique “Kingdom of Jordan” pre-tour adventure provides the Columbus Holy Land traveler an adventure into another part of the Bible Lands where prophets, kings, and Jesus Christ traversed. This tour highlights the major sites of Jordan prior to your Holy Land experience in Israel and Palestine. At the conclusion of our Jordan tour, you will be transferred to our tour group hotel in Netanya, Israel, for the start of our Holy Land tour. Day 1, Saturday. USA to Amman, Jordan. Depart your home city to Amman, the capital of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Day 2, Sunday. Arrive Amman. You will be met upon your arrival in Amman where you will be greeted by your tour host, Dann Hone, and transferred to your deluxe Mövenpick Hotel Amman. Day 3, Monday. Amman & Jerash Today we journey north from the Jordanian capital city of Amman (known in Greco-Roman times as Philadelphia) to Jerash, the monumental Graeco-Roman Decapolis city, visiting its magnificent ruins and review Old and New Testament events that occurred along the route. We will cross the Jabbok River near Penuel and recall that the patriarch Jacob was renamed “Israel” at its banks after wrestling with an angel all through the night. You return to Amman for visits to the famous downtown Souk (open-air market), Amman Citadel, location of the Jordan Archaeological Museum (houses some of the Dead Sea Scrolls), Temple of Hercules, and other significant sites. -

Jordan Experience Study Guide

Jordan Experience Study Guide Page 1 of 52 Amman 4 Al – Karak 8 Aqaba 13 Dead Sea 17 Jerash 19 Lot’s Cave 24 Machaerus 27 Madaba 29 Mount Nebo 30 Penuel 34 Petra 35 Red Sea 41 Tishbe 44 Umm Ar-Rasas 46 Umm Qais 47 in’Ma Zarqa 51 Page 2 of 52 Page 3 of 52 Amman Being situated north, Amman is the administrative centre of the Amman Governorate. It is the capital and most populated city of Jordan, considered to be one of the most liberal and modernized Arab cities. ‘Ain Ghazal is the earliest known settlement dating back to the Neolithic site, Amman itself being built on the site of “Rabbath Ammon” an Iron Age settlement, the capital of the Ammonites. During the Greek and Roman periods it was known as Philadelphia before being renamed as Amman. Modern Amman dates back to the 19th century AD, being abandoned for most of the medieval and post medieval periods, when a new village developed with its municipality being birthed in 1909. Starting on seven hills, it has expanded over 19 hills, combining 27 district, which are managed by the Greater Amman Municipality with Yousef Al-Shawarbeh as its mayor. Each are is named after the hills they occupy or the valleys. The west of Amman is more modern and serves as the economic centre of the city while the East side of Amman is filled with historuc sites that host cultural activities. Being found on the outskirts of Amman in 1974 by construction workers, the site of ‘Ain Ghazal was presumed to be inhabited 3000 during the 7000 BC, being a typical aceramic Neolithic village with rectangular mud-bricked buildings with walls made up of lime plaster. -

Biography of Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan

001 m 17 6,111IM , 1~ I ~A~ 7 IIr ILl .ii: ve ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © 46J& JI JjA- e. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher or the translator. Published by: '*4. j Ji a..4RJ Li - DARUSSALAM Publishers and Distributors P.O. Box 22743, Riyadh 11416 Tel. 4033962 - Fax: 4021659 Kingdom of Saudi Arabia Printed in July, 1997 Printing supervised by ABDUL MALIK MUJAHID Computerized Typesetting, designing and proof reading carried out at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia under the supervision of Dr. Muhammad Muhsin Khan assisted by a team of highly qualified persons. () Maktaba Dar us Salam, 1997 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data Al-B ukhari, Muhanimed Ibn Ismaiel Sahih A1-Bukhari\ translated by Muhammad Muhsin Khan.- Riyadh. 500p., 14x2lcm ISBN: 9960-717-31-3 (set) 9960-717-31-1 (v.1) 1- Al-Hadith - Six books I- Khan, Muhammad Muhsin (tr.) II-Title 235.1 dc 0887/18 Legal Deposit no. 0887/18 ISBN: 9960-717-31-3 (set) 9960-717-32-1 (v.11) *1 (-&~?I I- ~ ~- 4t 4J,j LJ 4i A3 4L*J LJJ U ç JI ç L jZJ L )y& y*J & y*JI 4~.L A1 d JyL Lb 4, ii-i- Lk,t.;j <L4 (Vl-liL----l- t,iJt -. r- SIR. : 4I ZJ4L 4L z9n Z.Lil LI R4i1, 4JJj ZUJ Jt JL •4JI '- LJ UJI Ijt4 ?U) , _Joi LL.L, 4J1 L4 J JI 4JIJ. -

A Study of an Arabic Manuscript

JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) CHAIRMAN OF EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Hajar A. HAJAR AL BINALI (Qatar) EDITORS IN CHIEF Dr. Ayşegiil DEMIRHAN ERDEMIR (Turkey) Dr. Abdul Nasser KAADAN (Syria) ASSOCIATE EDITORS Dr. Oztan USMANBAŞ(Turkey) Dr. Sharif KafAL-GHAZAL (England) EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Mahdi MUHAQAK (Iran) Dr. Husain NAGAMIA (USA) Dr. Nil SARI (Turkey) Dr. Faisal ALNASIR (Bahrain) Dr. Mostafa SHEHATA (Egypt) Dr. Rachel HAJAR (Qatar) INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD Dr. Alain TOUWAIDE (Belgium) Dr. Taha AL-JASSER (Syria) Dr. Ahmad KANAAN (KSA) Dr. Rolando NERI-VELA (Mexico) Dr. David W. TSCHANZ (KSA) Dr. Zafar Afaq ANSARI (Malaysia) Dr. Abed Ameen YAGAN (Syria) Dr. Husaini HAFIZ (Singapore) Dr. Salim AYDÜZ (Turkey) Dr. Talat Masud YELBUZ (USA) Dr. Keishi HASEBE (Japan) Dr. Mohamed RASH ED (Libya) Dr. Mustafa Abdul RAHMAN (France) Dr. Nabil El TABBAKH (Egypt) Dr. Bacheer AL-KATEB (Syria) Dr. Hakim Naimuddin ZUBAIRY (Pakistan) Dr. Plinio PRIORESCHI (USA) Dr. Ahmad CHAUDHRY (England) Hakim Syed Z. RAHMAN (India) Dr. Fraid HADDAD (USA) Dr. Abdul Mohammed KAJBFZADEH (Iran) Dr. Ibrahim SYED (USA) Dr. Nancy GALLAGHER (USA) Dr. Henry Amin AZAR (USA) Dr. Riem HAWI (Germany) Dr. Gary FERNGREN (USA) Dr. Esin KAHYA (Turkey) Dr. Ann NAM AL (Turkey) Dr. Mamoun MO BAYED (England) Dr. Hanzade DOGAN (Turkey) I JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC MEDICINE (JISHIM) Periods: Journal of ISHIM is published twice a year in April and October. Address Changes: The publisher must be informed at least 15 days before the publication date. All articles, figures, photos and tables in this journal can not be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher.