The History of the Chemical Weapons Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Okinawa - the Pentagon’S Toxic Junk Heap of the Pacific 沖縄、太平 洋のペンタゴン毒性ゴミ溜め

The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Volume 11 | Issue 47 | Number 6 | Nov 22, 2013 Okinawa - The Pentagon’s Toxic Junk Heap of the Pacific 沖縄、太平 洋のペンタゴン毒性ゴミ溜め Jon Mitchell Japanese translationavailable have contained kitchen or medical waste.4 (http://besobernow-yuima.blogspot.jp/2013/11/ja However, the conclusions of the Japanese and panfocus_27.html) international scientific community were unequivocal: Not only did the barrels disprove Pentagon denials of the presence of military Decades of Pentagon pollution poison servicedefoliants in Japan, the polluted land posed a members, local residents and the future of the island.threat to the health of local residents and required immediate remediation.5 In June 2013, construction workers unearthed more than 20 rusty barrels from beneath a soccer * * * pitch in Okinawa City. The land had once been The Pentagon is the largest polluter on the part of Kadena Air Base - the Pentagon’s largest planet.6 installation in the Pacific region - but was returned to civilian usage in 1987. Tests revealed Producing more toxic waste than the U.S.A.’s top that the barrels contained two ingredients of three chemical manufacturers combined, in 2008 military defoliants used in the Vietnam War - the 25,000 of its properties within the U.S. were herbicide 2,4,5-T and 2,3,7,8-TCDD dioxin. Levels found to be contaminated. More than 100 of thee of the highly toxic TCDD in nearby water were classified by the Environmental Protection 1 measured 280 times safe limits. Agency as Superfund sites which necessitated urgent clean-up.7 The Pentagon has repeatedly denied the storage of defoliants - including Agent Orange - on Although Okinawa Island hosts more than 30 2 Okinawa. -

Chemical Munitions Igloos for the Container Storage of Wastes Generated from the Maintenance of the Chemical Munitions Stockpile Attachment D.2

Tooele Army Depot - South Hazardous Wae Storage Permit Permit Attachment 12 - Container Management Modification Date: March 3. 1994 Chemical Munitions Igloos for the Container Storage of Wastes Generated from the Maintenance of the Chemical Munitions Stockpile Attachment D.2. Containers with Free Liquids The stockpile of chemical munitions stored at TEAD(S) (which included the M-55 rockets before they were declarbed obsolete, and became a hazardous waste) requires continual maintenance. These maintenance activities generate wastes, examples of which are: The valves and plugs used on ton containers used to store bulk chemical agent are changed out on a periodic basis, the valves and plugs that are removed are decontaminated, containerized, and managed as a hazardous waste. Wastes of this type would typically carry waste numbers F999 and/or P999, in addition to other waste numbers where applicable. Discarded protective clothing (including suites, boots, gloves, canister to personnel breathing apparatus, etc.) is containerized and managed as a hazardous waste. Certain types of impregnated carbon have been found to contain chromium and silver in leachable quantities exceeding the TCLP criteria for hazardous waste. In such cases, EPA Waste Numbers D007 and DOll would be assigned to these wastes in addition to any other applicable hazardous waste numbers. Any indoor area where chemical agents, or agent filled munitions are stored has the potential to be ventilated. The air removed from the area passes through a bed of activated carbon before being released to the atmosphere. When the activated charcoal is changed out, the spent' carbon is containerized, and managed as a hazardous waste. -

Desind Finding

NATIONAL AIR AND SPACE ARCHIVES Herbert Stephen Desind Collection Accession No. 1997-0014 NASM 9A00657 National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC Brian D. Nicklas © Smithsonian Institution, 2003 NASM Archives Desind Collection 1997-0014 Herbert Stephen Desind Collection 109 Cubic Feet, 305 Boxes Biographical Note Herbert Stephen Desind was a Washington, DC area native born on January 15, 1945, raised in Silver Spring, Maryland and educated at the University of Maryland. He obtained his BA degree in Communications at Maryland in 1967, and began working in the local public schools as a science teacher. At the time of his death, in October 1992, he was a high school teacher and a freelance writer/lecturer on spaceflight. Desind also was an avid model rocketeer, specializing in using the Estes Cineroc, a model rocket with an 8mm movie camera mounted in the nose. To many members of the National Association of Rocketry (NAR), he was known as “Mr. Cineroc.” His extensive requests worldwide for information and photographs of rocketry programs even led to a visit from FBI agents who asked him about the nature of his activities. Mr. Desind used the collection to support his writings in NAR publications, and his building scale model rockets for NAR competitions. Desind also used the material in the classroom, and in promoting model rocket clubs to foster an interest in spaceflight among his students. Desind entered the NASA Teacher in Space program in 1985, but it is not clear how far along his submission rose in the selection process. He was not a semi-finalist, although he had a strong application. -

U.S. Disposal of Chemical Weapons in the Ocean: Background and Issues for Congress

Order Code RL33432 U.S. Disposal of Chemical Weapons in the Ocean: Background and Issues for Congress Updated January 3, 2007 David M. Bearden Analyst in Environmental Policy Resources, Science, and Industry Division U.S. Disposal of Chemical Weapons in the Ocean: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The U.S. Armed Forces disposed of chemical weapons in the ocean from World War I through 1970. At that time, it was thought that the vastness of ocean waters would absorb chemical agents that may leak from these weapons. However, public concerns about human health and environmental risks, and the economic effects of potential damage to marine resources, led to a statutory prohibition on the disposal of chemical weapons in the ocean in 1972. For many years, there was little attention to weapons that had been dumped offshore prior to this prohibition. However, the U.S. Army completed a report in 2001 indicating that the past disposal of chemical weapons in the ocean had been more common and widespread geographically than previously acknowledged. The Army cataloged 74 instances of disposal through 1970, including 32 instances off U.S. shores and 42 instances off foreign shores. The disclosure of these records has renewed public concern about lingering risks from chemical weapons still in the ocean today. The risk of exposure to chemical weapons dumped in the ocean depends on many factors, such as the extent to which chemical agents may have leaked into seawater and been diluted or degraded over time. Public health advocates have questioned whether contaminated seawater may contribute to certain symptoms among coastal populations, and environmental advocates have questioned whether leaked chemical agents may have affected fish stocks and other marine life. -

® Chemical Weapons Convention Bulletin

® CHEMICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION BULLETIN ISSUE NO. 2 Autumn 1988 Published by the Federation of American Scientists Fund (FAS Fund) THE PROPOSED CHEMICAL WEAPONS CONVENTION: AN INDUSTRY PERSPECTIVE Kyle B. Olson Associate Director for Health, Safety and Chemical Regulations Chemical Manufacturers Association, Washington DC On October 12, 1987, the Board of Directors of the US Chemical Manu """facturers Association (CMA) adopted a policy of support for the Chemical Weapons Convention. CMA is a nonprofit trade association whose members represent over 90% of the basic chemical productive capacity of the united states. CMA has been, if not the sole, then certainly the strongest advo cate of industry's interests in the debate on a chemical weapons treaty. CMA traces its involvement in this issue back nearly a decade, though for many of those years it was a priority issue for only a limited number of companies. It had its home at CMA in a special panel funded and staffed by companies with an interest in phosphorous compounds. This was because of the early concentration of interest by diplomats in the CW agents based on phosphorous. Activity during this period was steady but generally low key, with a few lonely individuals carrying the industry's concerns on their backs. In early 1987, however, CMA decided to throw the issue into the main stream of its operations. The small phosphorous-focused panel was dis solved and the group was reconstituted within the Technical Department of ~he Association. This move, which , Jreatly expanded the number of com panies and professionals involved in the issue, occurred just as major shifts in the Soviet Union's negotiat ing position were sending the Geneva talks on an exhilarating rollercoaster ride. -

Chemical Weapons Technology Section 4—Chemical Weapons Technology

SECTION IV CHEMICAL WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY SECTION 4—CHEMICAL WEAPONS TECHNOLOGY Scope Highlights 4.1 Chemical Material Production ........................................................II-4-8 4.2 Dissemination, Dispersion, and Weapons Testing ..........................II-4-22 • Chemical weapons (CW) are relatively inexpensive to produce. 4.3 Detection, Warning, and Identification...........................................II-4-27 • CW can affect opposing forces without damaging infrastructure. 4.4 Chemical Defense Systems ............................................................II-4-34 • CW can be psychologically devastating. • Blister agents create casualties requiring attention and inhibiting BACKGROUND force efficiency. • Defensive measures can be taken to negate the effect of CW. Chemical weapons are defined as weapons using the toxic properties of chemi- • Donning of protective gear reduces combat efficiency of troops. cal substances rather than their explosive properties to produce physical or physiologi- • Key to employment is dissemination and dispersion of agents. cal effects on an enemy. Although instances of what might be styled as chemical weapons date to antiquity, much of the lore of chemical weapons as viewed today has • CW are highly susceptible to environmental effects (temperature, its origins in World War I. During that conflict “gas” (actually an aerosol or vapor) winds). was used effectively on numerous occasions by both sides to alter the outcome of • Offensive use of CW complicates command and control and battles. A significant number of battlefield casualties were sustained. The Geneva logistics problems. Protocol, prohibiting use of chemical weapons in warfare, was signed in 1925. Sev- eral nations, the United States included, signed with a reservation forswearing only the first use of the weapons and reserved the right to retaliate in kind if chemical weapons were used against them. -

Medical Aspects of Chemical and Biological Warfare, Index

Index INDEX A Aircrew uniform, integrated battlefield (AUIB), 373 Air delivery Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, 398, 409–410 history, 28, 31, 34–35, 49–50 See also Edgewood Arsenal, Maryland See also Aerosol; Inhalational injury; specific agent ABG Airplane smoke tanks, 31 See Arterial blood gases (ABG) AIT Abortion See Aeromedical Isolation Team (AIT) septic, in brucellosis, 516 Alarms, 377–383 Abrin, 610, 632 biological agent, 431 Abrus precatorius, 610, 632 history, 23, 53, 60–62, 66–67 AC LOPAIR, E33 Area Scanning, 53 See Hydrogen cyanide (AC) M8A1 Automatic Chemical Agent, 380–381 Acetaminophen, 627 M21 Remote Sensing Chemical Agent (RSCAAL), 381 Acetylcholine (ACh), 132–134, 136, 159, 647 Portable Automatic Chemical Agent, 60–62 Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), 131–132, 134, 182–184 See also Detection Acetylene tetrachloride, 34 Alastrim, 543 Acid hydrolysis, 355 Alexander, Stewart, 103 Action potential, 133 Algal toxins, 457, 609, 617 Activated charcoal, 217, 362–363, 366, 370, 373, 670 Alimentary toxic aleukia (ATA), 659, 667 Adamsite Alkaline hydrolysis, 355 See DM (diphenylaminearsine) Allergic contact sensitivity, 238–239, 249, 314, 316–317 Additives, 122 a -Naphthylthiourea (ANTU), 638 Adenine arabinoside (Ara-A), 553 Alphaviruses, 562 Adenosine triphosphate (ATP), 275, 383, 431 antigenic classification, 564–565 S-Adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase inhibitors, 552 structure and replication, 569–570 Adenoviridae, 575, 683 See also Viral encephalitides; specific virus Adrenaline, 132 Alphavirus virion, 569 Adrenergic nervous system, -

NSIAD-95-67 Chemical Weapons: Stability of the U.S. Stockpile

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Subcommittee GAO on Environment, Energy, and Natural Resources, Committee on Government Operations, House of Representatives December 1994 CHEMICAL WEAPONS Stability of the U.S. Stockpile GAO/NSIAD-95-67 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-259506 December 22, 1994 The Honorable Mike Synar Chairman, Subcommittee on Environment, Energy, and Natural Resources Committee on Government Operations House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: Since 1985, the U.S. Army has been working to implement congressional direction to dispose of the U.S. stockpile of unitary1 chemical weapons and agents—a process the Army currently estimates will cost $8.5 billion. Because the Army continues to experience delays in implementing its disposal program and may have to store the stockpile longer than planned, you asked us to review the Army’s (1) prediction of how long chemical weapons can be stored safely and (2) contingency plans for disposing of chemical weapons that become dangerous. Background In November 1985, Congress passed Public Law 99-145 directing the Department of Defense (DOD) to destroy its stockpile of unitary chemical agents and weapons by September 30, 1994. The weapons are stored at eight sites in the continental United States and on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. (See app. I for the stockpile munitions and storage locations.) To comply with the congressional direction, the Army, DOD’s lead service in chemical matters, developed a plan to burn the stockpile on-site in specially designed high-temperature incinerators. -

Restoration | Appendix S: Sea Disposal of Military Munitions Agent Weight (NCAW) of CWM According to the CA and Disposal Location

disposed of in U.S. coastal waters. It also identifies sites where conventional military munitions were disposed of in these waters. DoD’s research into sea disposal of CWM has identified approximately 30,000 tons of disposed CA at 21 sites in U.S. coastal waters. The term CA, as used in this appendix, is limited to those substances on the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) schedule of chemicals. Figure S-1 provides a summary of the net chemical Restoration | Appendix S: Sea Disposal of Military Munitions agent weight (NCAW) of CWM according to the CA and disposal location. NCAW totals were determined using assumptions regarding the container sizes and densities Under Section 314 of the Fiscal Year (FY) 2007 In the interim, DoD will report, annually, any new of the disposed materials. National Defense Authorization Act, the Department information identified during the review. of Defense (DoD) is required to conduct a historical Figure S-2 displays the locations of each disposal This interim report identifies the Department’s review of available records to determine the number, site in U.S. coastal waters. progress on the historical review since FY2006. size, and probable locations of sites where the Specifically, this report updates the general Figures S-3 through S-32 provide information on each military disposed of military munitions in U.S. locations, types, and quantities of chemical disposal site. For CWM disposal sites, these figures coastal waters. The Department will include the munitions or chemical agents (CA), collectively include CA type, the type of munition or container, the final Section 314 report in the FY2009 Defense referred to as chemical warfare material (CWM), quantity that was sea disposed, and the NCAW. -

Disposal of Chemical Weapons: Alternative Technologies (Part 4 of 8)

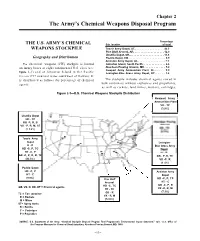

Chapter 2 The Army’s Chemical Weapons Disposal Program Percentage THE U.S. ARMY’S CHEMICAL Site Iocation of total WEAPONS STOCKPILE Tooele Army Depot, UT,. 42.3 Pine Bluff Arsenal, AR. 12.0 Umatilla Depot, OR... 11.6 Geography and Distribution Pueblo Depot, CO. 9.9 Anniston Army Depot, AL.. 7.1 The chemical weapons (CW) stockpile is located Johnston Island, South Pacific . 6.6 on Army bases at eight continental U.S. sites (see Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD. 5.0 Newport Army Ammunition Plant, IN...... 3.9 figure 2-1) and at Johnston Island in the Pacific Lexington-Blue Grass Army Depot, KY. 1.6 Ocean (717 nautical miles southwest of Hawaii). It is distributed as follows (by percentage of chemical The stockpile includes chemical agents stored in agent): bulk containers without explosives and propellants, as well as rockets, land mines, mortars, cartridges, Figure 2-1—U.S. Chemical Weapons Stockpile Distribution I Newport Army I Ammunition Plant I VX - TC / (3.9%) Umatilla Depot HD - TC GB -P, R, B VX - P, R, M, ST (1 1.6%) Tooele Army Depot Lexington- H-P Blue Grass Army HD -C, P, TC HT -C, P GB -C, P, R, B, TC GB - P, R, TC (42.3%) VX -P, R (1 .6%) Pueblo Depot HD -C, P Anniston Army HT - C Depot (9.9%) Pine Bluff HD -C, P, TC Arsenal HT - C HD -C, TC GB -C, P, R GB, VX, H, HD, HT = Chemical agents. HT - TC VX -P, R, M GB - R (7.1%) TC = Ton container VX - R, M R = Rockets (12.0%) M = Mines ST= Spray tanks B = Bombs C = Cartridges P = Projectiles SOURCE: U.S. -

Milestones in U.S. Chemical Weapons Storage and Destruction with More Than 2,600 Dedicated Employees Plus Contractor Support Staff, the U.S

Milestones in U.S. Chemical Weapons Storage and Destruction With more than 2,600 dedicated employees plus contractor support staff, the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency (CMA) leads the world in chemical weapons destruction with a demonstrated history of safely storing, recovering, assessing and disposing of U.S. chemical weapons and related materials. CMA manages all U.S. chemical materiel except for the disposal of two weapons stockpiles that fall under the Department of Defense’s U.S. Army Element Assembled Chemical Weapons Alternatives pilot neutralization program. Through its Chemical Stockpile Emergency Preparedness Program, CMA works with local emergency preparedness and response agencies at weapons stockpile locations. 1960-1982 1960s and before 1971 1979 The United States begins stockpiling and The United States finishes transferring The Army constructs and begins using chemical weapons against Germany chemical munitions from Okinawa, Japan, operating the Chemical Agent in World War I, which lasts from 1914 to to Johnston Island, located about 800 Munitions Disposal System (CAMDS), 1918. The weapons are securely stored miles from Hawaii, in September of 1971. a pilot incineration facility located at U.S. military installations at home at what is now the Deseret Chemical and abroad. 1972 Depot (DCD), Utah. The Army tests disposal equipment and processes The Edgewood Arsenal, Md., produces The Army forms the U.S. Army Materiel at the plant. More than 91 tons of mustard and phosgene but the Arsenal Command’s Program Manager for chemical agent are safely destroyed. is not large enough to store the agent Demilitarization of Chemical Materiel, and new installations are constructed in headquartered at Picatinny Arsenal, Huntsville, Ala., Denver, Colo., Pine Bluff, near Dover, NJ. -

Umatilla Chemical Agent Disposal Facility

INCHING AWAY FROM ARMAGEDDON: DESTROYING THE U.S. CHEMICAL WEAPONS STOCKPILE April 2004 By Claudine McCarthy and Julie Fischer, Ph.D. With the assistance of Yun Jung Choi, Alexis Pierce and Gina Ganey The Henry L. Stimson Center Introduction i Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from The Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. The Henry L. Stimson Center 11 Dupont Circle, NW 9th Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org ii The Henry L. Stimson Center Introduction INTRODUCTION On 3 September 2003, the Department of Defense issued a press release noting that the United States (US) would be unable to meet the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) deadline for the destruction of 45 percent of its chemical weapons stockpile by 27 April 2004.1 This announcement also indirectly confirmed that the United States will be unable to meet the CWC’s deadline for destroying its entire stockpile by 27 April 2007. The treaty allows for a five-year extension of this final deadline, which the United States will likely need to request as that date draws closer. Chemical weapons destruction is the exception to the old adage that it is easier to destroy than to create. While some of the toxic agents are stored in bulk containers that must be emptied, their contents neutralized, and the contaminated containers destroyed, more remain in weaponized form (inside rockets, bombs, landmines, and other armaments) in storage igloos at six sites in the US.