Transformation and Composition of the Komnenos “Clan” (1081–1200) – a Statistical Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger – the First One Not to Become a Blind Man? Political and Military History of the Bryennios Family in the 11Th and Early 12Th Century

Studia Ceranea 10, 2020, p. 31–45 ISSN: 2084-140X DOI: 10.18778/2084-140X.10.02 e-ISSN: 2449-8378 Marcin Böhm (Opole) https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5393-3176 Nikephoros Bryennios the Younger – the First One Not to Become a Blind Man? Political and Military History of the Bryennios Family in the 11th and Early 12th Century ikephoros Bryennios the Younger (1062–1137) has a place in the history N of the Byzantine Empire as a historian and husband of Anna Komnene (1083–1153), a woman from the imperial family. His historical work on the his- tory of the Komnenian dynasty in the 11th century is an extremely valuable source of information about the policies of the empire’s major families, whose main goal was to seize power in Constantinople1. Nikephoros was also a talented commander, which he proved by serving his father-in-law Alexios I Komnenos (1081–1118) and brother-in-law John II Komnenos (1118–1143). The marriage gave him free access to people and documents which he also enriched with the history of his own family. It happened because Nikephoros Bryennios was not the first representative of his family who played an important role in the internal policy of the empire. He had two predecessors, his grandfather, and great grand- father, who according to the family tradition had the same name as our hero. They 1 J. Seger, Byzantinische Historiker des zehnten und elften Jahrhunderts, vol. I, Nikephoros Bryennios, München 1888, p. 31–33; W. Treadgold, The Middle Byzantine Historians, Basingstoke 2013, p. 344–345; A. -

La Sainte Face De Laon

Université de Montréal Faculté des études supérieures et post-doctorales Ce mémoire intitulé : LA SAINTE FACE DE LAON Présenté par : Nicole Sabourin Département d’Histoire de l’Art et d’Études Cinématographiques Faculté des Arts Et des Sciences A été évalué par un jury composé des personnes suivantes : Ersy Contogouris, présidente-rapporteuse Sarah Guérin, directrice de recherche Robert Marcoux, membre du jury Août 2017 © Nicole Sabourin i Résumé La cathédrale de Laon conserve dans son trésor une précieuse icône du 13e siècle appelée Sainte Face de Laon. Selon la tradition, en 1249 Jacques Pantaléon de Troyes, chapelain du pape à Rome et futur pape Urbain IV envoie à sa sœur Sybille alors abbesse du monastère cistercien de Montreuil-en-Thiérache (Picardie) cette image sainte, copie du Mandylion d’Édesse. Une lettre, maintenant disparue, accompagne cet envoi. Une double inscription sur l’icône, une première en caractères cyrilliques et en slavon ancien et une autre en langue grecque pose encore aujourd’hui des interrogations sur l’origine de l’icône, soit russe, bulgare ou serbe. Cette recherche a pour but d’explorer les possibilités d’une origine serbe de l’icône de Laon et de retracer son trajet entre la Serbie et la France, via Rome. Pour y arriver nous ferons un détour historique à travers l’histoire de la Serbie dirigée à cette époque par la dynastie des Nemanjić, fondateurs de monastères en Serbie, en Italie byzantine et grands donateurs d’icônes et d’objets liturgiques y compris à la basilique Saint-Nicolas-de-Bari. L’origine orthodoxe de l’icône pose la question des déplacements d’œuvres entre l’Orient et l’Occident et celle de la circulation des artistes entre Constantinople et les pays limitrophes après le sac de Constantinople de 1204. -

BYZANTINE CAMEOS and the AESTHETICS of the ICON By

BYZANTINE CAMEOS AND THE AESTHETICS OF THE ICON by James A. Magruder, III A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland March 2014 © 2014 James A. Magruder, III All rights reserved Abstract Byzantine icons have attracted artists and art historians to what they saw as the flat style of large painted panels. They tend to understand this flatness as a repudiation of the Classical priority to represent Nature and an affirmation of otherworldly spirituality. However, many extant sacred portraits from the Byzantine period were executed in relief in precious materials, such as gemstones, ivory or gold. Byzantine writers describe contemporary icons as lifelike, sometimes even coming to life with divine power. The question is what Byzantine Christians hoped to represent by crafting small icons in precious materials, specifically cameos. The dissertation catalogs and analyzes Byzantine cameos from the end of Iconoclasm (843) until the fall of Constantinople (1453). They have not received comprehensive treatment before, but since they represent saints in iconic poses, they provide a good corpus of icons comparable to icons in other media. Their durability and the difficulty of reworking them also makes them a particularly faithful record of Byzantine priorities regarding the icon as a genre. In addition, the dissertation surveys theological texts that comment on or illustrate stone to understand what role the materiality of Byzantine cameos played in choosing stone relief for icons. Finally, it examines Byzantine epigrams written about or for icons to define the terms that shaped icon production. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Famouskin.Com Relationship Chart of Charles Darwin Theory of Evolution 19Th Cousin 2 Times Removed of Thomas Sim Lee 2Nd and 7Th Governor of Maryland

FamousKin.com Relationship Chart of Charles Darwin Theory of Evolution 19th cousin 2 times removed of Thomas Sim Lee 2nd and 7th Governor of Maryland Isaac II Angelos - - - - - - - - - - - Irene Angelina Irene Angelina Philip of Swabia Philip of Swabia Marie of Hohenstaufen Marie of Hohenstaufen Henry II, Duke of Brabant Henry II, Duke of Brabant Matilda of Brabant Matilda of Brabant Robert I, Count of Artois Robert I, Count of Artois Blanche of Artois Blanche of Artois Edmund Plantagenet Edmund Plantagenet Henry Plantagenet Henry Plantagenet Maud de Chaworth Maud de Chaworth Eleanor Plantagenet Eleanor Plantagenet Richard FitzAlan Richard FitzAlan Alice FitzAlan Sir Richard FitzAlan FamousKin.comSir Thomas de Holand Elizabeth de Bohun A B © 2010-2021 FamousKin.com Page 1 of 3 30 Sep 2021 FamousKin.com Relationship Chart of Charles Darwin to Thomas Sim Lee A B Margaret de Holand Elizabeth FitzAlan Sir John Beaufort Sir Robert Goushill Edmund Beaufort Joan Goushill Eleanor Beauchamp Sir Thomas Stanley Eleanor Beaufort Katherine Stanley Sir Robert Spencer Sir John Savage Margaret Spencer Dulcia Savage Sir Thomas Carey Sir Henry Bold Sir William Carey Maud Bold Mary Boleyn Thomas Gerard Catherine Carey Jennet Gerard Sir Francis Knollys Richard Eltonhead Henry Knollys William Eltonhead Margaret Cave Anne Bowers Lettice Knollys Richard Eltonhead William Paget Anne Sutton William Paget Alice Eltonhead Frances Rich Henry Corbin Penelope Paget Laetitia Corbin FamousKin.comPhilip Foley Richard Lee C D © 2010-2021 FamousKin.com Page 2 of 3 30 Sep 2021 FamousKin.com Relationship Chart of Charles Darwin to Thomas Sim Lee C D Paul Foley Philip Lee Elizabeth Turton Sarah Brooke Penelope Foley Thomas Lee Charles Howard Christiana Sim Mary Howard Thomas Sim Lee Erasmus Darwin 2nd and 7th Governor of Maryland Dr. -

The Daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the Wife of a GalicianVolhynian Prince

The daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the wife of a GalicianVolhynian Prince «The daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the wife of a GalicianVolhynian Prince» by Alexander V. Maiorov Source: Byzantinoslavica Revue internationale des Etudes Byzantines (Byzantinoslavica Revue internationale des Etudes Byzantines), issue: 12 / 2014, pages: 188233, on www.ceeol.com. The daughter of a Byzantine Emperor – the wife of a Galician-Volhynian Prince Alexander V. MAIOROV (Saint Petersburg) The Byzantine origin of Prince Roman’s second wife There is much literature on the subject of the second marriage of Roman Mstislavich owing to the disagreements between historians con- cerning the origin of the Princeís new wife. According to some she bore the name Anna or, according to others, that of Maria.1 The Russian chronicles give no clues in this respect. Indeed, a Galician chronicler takes pains to avoid calling the Princess by name, preferring to call her by her hus- band’s name – “âĺëčęŕ˙ ęí˙ăčí˙ Ðîěŕíîâŕ” (Roman’s Grand Princess).2 Although supported by the research of a number of recent investiga- tors, the hypothesis that she belonged to a Volhynian boyar family is not convincing. Their arguments generally conclude with the observation that by the early thirteenth century there were no more princes in Rusí to whom it would have been politically beneficial for Roman to be related.3 Even less convincing, in our opinion, is a recently expressed supposition that Romanís second wife was a woman of low birth and was not the princeís lawful wife at all.4 Alongside this, the theory of the Byzantine ori- gin of Romanís second wife has been significantly developed in the litera- ture on the subject. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) and the Western Way of War the Komnenian Armies

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 11 (2008-2009) Viewpoints 1 The Eastern Roman Empire (Byzantium) and the Western Way of War The Komnenian Armies Byzantium. The word invokes to the modern imagination images of icons, palaces and peaceful Christianity rather than the militarism associated with its European counterparts during the age of the Byzantine Empire. Despite modern interpretations of the Empire, it was not without military dynamism throughout its 800-year hold on the East. During the “Second Golden Age” of Byzantium, this dominion experienced a level of strength and discipline in its army that was rarely countered before or after. This was largely due to the interest of the Komnenian emperors in creating a military culture and integrating foreign ideas into the Eastern Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire faced unique challenges not only because of the era in which they were a major world power but also for the geography of Byzantium. Like the Rome of earlier eras, the territory encompassed by Byzantium was broad in scope and encompassed a variety of peoples under one banner. There were two basic areas held by the empire – the Haemus and Anatolia, with outposts in Crete, the Crimea and southern Italy and Sicily (Willmott 4). By the time of the Komnenos dynasty, most of Anatolia had been lost in the battle of Manzikert. Manuel I would attempt to remedy that loss, considered significant to the control of the empire. Of this territory, the majority was arid or mountainous, creating difficulties for what was primarily an agricultural economy. This reliance on land-based products helped to bolster the reluctance for war in the eastern Roman Empire. -

Heineman Royal Ancestors Medieval Europe

HERALDRYand BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE HERALDRY and BIOGRAPHIES of the HEINEMAN ROYAL ANCESTORS of MEDIEVAL EUROPE INTRODUCTION After producing numerous editions and revisions of the Another way in which the royal house of a given country familiy genealogy report and subsequent support may change is when a foreign prince is invited to fill a documents the lineage to numerous royal ancestors of vacant throne or a next-of-kin from a foreign house Europe although evident to me as the author was not clear succeeds. This occurred with the death of childless Queen to the readers. The family journal format used in the Anne of the House of Stuart: she was succeeded by a reports, while comprehensive and the most popular form prince of the House of Hanover who was her nearest for publishing genealogy can be confusing to individuals Protestant relative. wishing to trace a direct ancestral line of descent. Not everyone wants a report encumbered with the names of Unlike all Europeans, most of the world's Royal Families every child born to the most distant of family lines. do not really have family names and those that have adopted them rarely use them. They are referred to A Royal House or Dynasty is a sort of family name used instead by their titles, often related to an area ruled or by royalty. It generally represents the members of a family once ruled by that family. The name of a Royal House is in various senior and junior or cadet branches, who are not a surname; it just a convenient way of dynastic loosely related but not necessarily of the same immediate identification of individuals. -

Constantinople 1 L Shaped H

The Shroud of Turin in Constantinople? Paper I An analysis of the L Shaped markings on the Shroud of Turin and an examination of the Holy Mandylion and Holy Shroud in the Madrid Skylitzes © Pam Moon Introduction This paper begins by looking at the pattern of marks on the Shroud of Turin which look like an L shape. The paper examines [1] the folding patterns, [2] the probable cause of the burn marks, and argues, with Aldo Guerreschi and Michele Salcito that it is accidental damage from incense. [3] It compares the marks with the Hungarian Pray manuscript. [4] In the second part, the paper looks at the historical text The Synopsis of the Histories attributed to Ioannes (John) Skylitzes. The illustrated history is known as the Madrid Skylitzes. It is the only surviving illustrated manuscript for Byzantine history for the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries. The paper looks at images from the Madrid Skylitzes which relate to the Holy Mandylion, also known as the Image of Edessa. The Mandylion was the most precious artefact in the Byzantine empire and is repeatedly described as an image ‘not-made-by-hands.’ [5] The paper identifies a miniature in the Madrid Skylitzes (fol.26v; see below) which apparently shows the procession of a beheaded emperor Leon V in AD 820 and suggests that there could be a scribal error. The picture seems to show the Varangian Guard who arrived in Constantinople after AD 988, 168 years later. The picture may instead depict the procession of AD 1036, where the Holy Mandylion (and in some translations Holy Shroud) were carried though the streets of Constantinople. -

Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century

A “Truly Unmonastic Way of Life”: Byzantine Critiques of Monasticism in the Twelfth Century DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hannah Elizabeth Ewing Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Professor Timothy Gregory, Advisor Professor Anthony Kaldellis Professor Alison I. Beach Copyright by Hannah Elizabeth Ewing 2014 Abstract This dissertation examines twelfth-century Byzantine writings on monasticism and holy men to illuminate monastic critiques during this period. Drawing upon close readings of texts from a range of twelfth-century voices, it processes both highly biased literary evidence and the limited documentary evidence from the period. In contextualizing the complaints about monks and reforms suggested for monasticism, as found in the writings of the intellectual and administrative elites of the empire, both secular and ecclesiastical, this study shows how monasticism did not fit so well in the world of twelfth-century Byzantium as it did with that of the preceding centuries. This was largely on account of developments in the role and operation of the church and the rise of alternative cultural models that were more critical of traditional ascetic sanctity. This project demonstrates the extent to which twelfth-century Byzantine society and culture had changed since the monastic heyday of the tenth century and contributes toward a deeper understanding of Byzantine monasticism in an under-researched period of the institution. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my family, and most especially to my parents. iii Acknowledgments This dissertation is indebted to the assistance, advice, and support given by Anthony Kaldellis, Tim Gregory, and Alison Beach. -

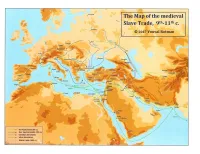

The Map Is Based on the Following Data Organized Chronologically and Geographically

The map is based on the following data organized chronologically and geographically Table 1: data concerning the slave trade in the medieval Mediterranean 8th-11th c. Western Europe Central Europe Italy-Adriatic Sea Syria-Palestine- Byzantium Balkans Caucasus-Black Iraq-Iran Egypt Sea-Russia 7th –8th c.: the 712: first Rhodian Sea Law kommerkiarioi, 729: Itil, first (mentions of attested in evidences 776: letter from trafficked slaves) Thessalonica 740: documents 762: Abbassids Pope Hadrian I to 728: last known (including of slaves) attesting Jews settle in Charlemagne sigillographical among the Baghdad regarding the mention of Khazars slave trade apothēkai 801: Irene lowers 8th c.: Abydikoi taxes (responsible of 812/814: the 809: Nicephorus I import taxes) of Franks leave the taxes slaves Thessalonica Adriatic Sea entering by the attested 822–852: al- 814–820: 824: Arab Dodecanese Ghazāl on the Byzantino- conquest of Crete Spain-Baltic Venetian edict routes against trade 833–844: Arab 841: the thema of 846: first 825: privileges with the Arabs raids in Sicily and 831–833: new Kherson version of granted by Louis 831: Arab Peloponnesus; kommerkiarioi mid-ninth Kitāb al- the Pious to a conquest of Byzantine raids century: Masālik wa’l- Jewish merchant Palermo in Syria 860: the Serbs pay -Life of George of mamālik, by of Sargossa 830–860: Arab their tribute to the Amastris (tax in Ibn 846: Agobard of raids in southern Bulgars in slaves Trebizond). Ḵhurradāḏhbih Lyons writes Italy 864: - Rus’ merchants : references to against the Christianization