Reassessing the Fair Tax University of Pittsburgh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tearing out the Income Tax by the (Grass)Roots

FLORIDA TAX REVIEW Volume 15 2014 Number 8 TEARING OUT THE INCOME TAX BY THE (GRASS)ROOTS by Lawrence Zelenak* Rich People’s Movements: Grassroots Campaigns to Untax the One Percent. By Isaac William Martin New York: Oxford University Press. 2013. I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 649 II. A CENTURY OF RICH PEOPLE’S ANTI-TAX MOVEMENTS ......... 651 III. EXPLAINING THE SUPPORT OF THE NON-RICH .......................... 656 IV. BUT WHAT ABOUT THE FLAT TAX AND THE FAIRTAX? ............ 661 V. THE RHETORIC OF RICH PEOPLE’S ANTI-TAX MOVEMENTS: PARANOID AND NON-PARANOID STYLES .................................... 665 VI. CONCLUSION ................................................................................. 672 I. INTRODUCTION Why do rich people seeking reductions in their tax burdens, who have the ability to influence Congress directly through lobbying and campaign contributions, sometimes resort to grassroots populist methods? And why do non-rich people sometimes join the rich in their anti-tax movements? These are the puzzles Isaac William Martin sets out to solve in Rich People’s Movements.1 Martin’s historical research—much of it based on original sources to which scholars have previously paid little or no attention—reveals that, far from being a recent innovation, populist-style movements against progressive federal taxation go back nearly a century, to the 1920s. Although Martin identifies various anti-tax movements throughout the past century, he strikingly concludes that there has been “substantial continuity from one campaign to the next, so that, in some * Pamela B. Gann Professor of Law, Duke Law School. 1. ISAAC WILLIAM MARTIN, RICH PEOPLE’S MOVEMENTS: GRASSROOTS CAMPAIGNS TO UNTAX THE ONE PERCENT (2013) [hereinafter MARTIN, RICH PEOPLE’S MOVEMENTS]. -

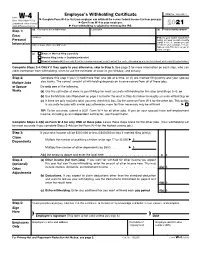

Form W-4, Employee's Withholding Certificate

Employee’s Withholding Certificate OMB No. 1545-0074 Form W-4 ▶ (Rev. December 2020) Complete Form W-4 so that your employer can withhold the correct federal income tax from your pay. ▶ Department of the Treasury Give Form W-4 to your employer. 2021 Internal Revenue Service ▶ Your withholding is subject to review by the IRS. Step 1: (a) First name and middle initial Last name (b) Social security number Enter Address ▶ Does your name match the Personal name on your social security card? If not, to ensure you get Information City or town, state, and ZIP code credit for your earnings, contact SSA at 800-772-1213 or go to www.ssa.gov. (c) Single or Married filing separately Married filing jointly or Qualifying widow(er) Head of household (Check only if you’re unmarried and pay more than half the costs of keeping up a home for yourself and a qualifying individual.) Complete Steps 2–4 ONLY if they apply to you; otherwise, skip to Step 5. See page 2 for more information on each step, who can claim exemption from withholding, when to use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App, and privacy. Step 2: Complete this step if you (1) hold more than one job at a time, or (2) are married filing jointly and your spouse Multiple Jobs also works. The correct amount of withholding depends on income earned from all of these jobs. or Spouse Do only one of the following. Works (a) Use the estimator at www.irs.gov/W4App for most accurate withholding for this step (and Steps 3–4); or (b) Use the Multiple Jobs Worksheet on page 3 and enter the result in Step 4(c) below for roughly accurate withholding; or (c) If there are only two jobs total, you may check this box. -

The Alternative Minimum Tax

Updated December 4, 2017 Tax Reform: The Alternative Minimum Tax The U.S. federal income tax has both a personal and a Individual AMT corporate alternative minimum tax (AMT). Both the The modern individual AMT originated with the Revenue corporate and individual AMTs operate alongside the Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-600) and operated in tandem with an regular income tax. They require taxpayers to calculate existing add-on minimum tax prior to its repeal in 1982. their liability twice—once under the rules for the regular Table 2 details selected key individual AMT parameters. income tax and once under the AMT rules—and then pay the higher amount. Minimum taxes increase tax payments Table 2. Selected Individual AMT Parameters, 2017 from taxpayers who, under the rules of the regular tax system, pay too little tax relative to a standard measure of Single/ Married their income. Head of Filing Married Filing Household Jointly Separately Corporate AMT Exemption $54,300 $84,500 $42,250 The corporate AMT originated with the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-514), which eliminated an “add-on” 28% bracket 187,800 187,800 93,900 minimum tax imposed on corporations previously. The threshold corporate AMT is a flat 20% tax imposed on a Source: Internal Revenue Code. corporation’s alternative minimum taxable income less an exemption amount. A corporation’s alternative minimum The individual AMT tax base is broader than the regular taxable income is the corporation’s taxable income income tax base and starts with regular taxable income and determined with certain adjustments (primarily related to adds back various deductions, including personal depreciation) and increased by the disallowance of a exemptions and the deduction for state and local taxes. -

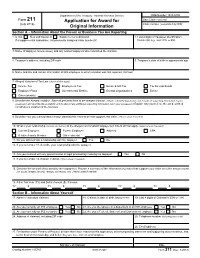

Form 211, Application for Award for Original Information

Department of the Treasury - Internal Revenue Service OMB Number 1545-0409 Form 211 Application for Award for Date Claim received (July 2018) Claim number (completed by IRS) Original Information Section A – Information About the Person or Business You Are Reporting 1. Is this New submission or Supplemental submission 2. Last 4 digits of Taxpayer Identification If a supplemental submission, list previously assigned claim number(s) Number(s) (e.g., SSN, ITIN, or EIN) 3. Name of taxpayer (include aliases) and any related taxpayers who committed the violation 4. Taxpayer's address, including ZIP code 5. Taxpayer's date of birth or approximate age 6. Name and title and contact information of IRS employee to whom violation was first reported, if known 7. Alleged Violation of Tax Law (check all that apply) Income Tax Employment Tax Estate & Gift Tax Tax Exempt Bonds Employee Plans Governmental Entities Exempt Organizations Excise Other (identify) 8. Describe the Alleged Violation. State all pertinent facts to the alleged violation. (Attach a detailed explanation and include all supporting information in your possession and describe the availability and location of any additional supporting information not in your possession.) Explain why you believe the act described constitutes a violation of the tax laws 9. Describe how you learned about and/or obtained the information that supports this claim. (Attach sheet if needed) 10. What is your relationship (current and former) to the alleged noncompliant taxpayer(s)? Check all that apply. (Attach sheet if needed) Current Employee Former Employee Attorney CPA Relative/Family Member Other (describe) 11. Do you still maintain a relationship with the taxpayer Yes No 12. -

2021 Instructions for Form 6251

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

Real Tax Reform: Flat-Tax Simplicity with a Progressive Twist Donald Marron

Real Tax Reform: Flat-Tax Simplicity with a Progressive Twist Donald Marron Abstract In a contribution to the Christian Science Monitor, Donald Document date: November 28, 2011 Marron agrees that there are good reasons for a simpler tax Released online: November 25, 2011 system, as found in the flat-tax plans of GOP hopefuls Perry, Gingrich, and Cain. But they need to be made more progressive to amount to real tax reform that can pass muster politically. Christian Science Monitor, The New Economy: Real Tax Reform: Flat-Tax Simplicity with a Progressive Twist Tax reform has emerged as a key issue for GOP presidential hopefuls. Texas Gov. Rick Perry wants to scrap our current system and replace it with a 20 percent flat tax on individual and corporate incomes. Former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich wants to do the same, but with even lower rates. Then there's pizza magnate Herman Cain. His "9-9-9" plan would replace today's income and payroll taxes with a trio of levies: a 9 percent flat tax on individuals, another on businesses, and a 9 percent retail sales tax. But Mr. Cain's ultimate vision is to eliminate anything remotely resembling today's tax system in favor of a national retail sales tax, which proponents call the FairTax. These three plans have much in common. Catchy names, for one. More important, they all focus on taxing consumption - what people spend - rather than income. The flat tax is most famous, of course, for applying a single rate to all corporate earnings and to all individual earnings above some exemption. -

The Viability of the Fair Tax

The Fair Tax 1 Running head: THE FAIR TAX The Viability of The Fair Tax Jonathan Clark A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Fall 2008 The Fair Tax 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Gene Sullivan, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Donald Fowler, Th.D. Committee Member ______________________________ JoAnn Gilmore, M.B.A. Committee Member ______________________________ James Nutter, D.A. Honors Director ______________________________ Date The Fair Tax 3 Abstract This thesis begins by investigating the current system of federal taxation in the United States and examining the flaws within the system. It will then deal with a proposal put forth to reform the current tax system, namely the Fair Tax. The Fair Tax will be examined in great depth and all aspects of it will be explained. The objective of this paper is to determine if the Fair Tax is a viable solution for fundamental tax reform in America. Both advantages and disadvantages of the Fair Tax will objectively be pointed out and an educated opinion will be given regarding its feasibility. The Fair Tax 4 The Viability of the Fair Tax In 1986 the United States federal tax code was changed dramatically in hopes of simplifying the previous tax code. Since that time the code has undergone various changes that now leave Americans with over 60,000 pages of tax code, rules, and rulings that even the most adept tax professionals do not understand. -

The Fairtax Treatment of Housing

A FairTaxsm White Paper The FairTax treatment of housing Advocates of tax reform share a common motivation: To iron out the mangled economic incentives resulting from statutory inequities and misguided social engineering that perversely cripple the American economy and the American people. Most importantly, ironing out the statutory inequities of the federal tax code need not harm homebuyers and homebuilders. The FairTax does more than do no harm. The FairTax encourages home ownership and homebuilding by placing all Americans and all businesses on equal footing – no loopholes, no exceptions. A specific analysis of the impact of the FairTax on the homebuilding industry/the housing market shows that the new homebuilding market would greatly benefit from enactment of the FairTax. The analysis necessarily centers upon two issues: (1) Whether the FairTax’s elimination of the home mortgage interest deduction (MID) adversely impacts the housing market (new and existing) in general, and home ownership and the homebuilding industry specifically; and (2) Whether the FairTax’s superficially disparate treatment of new vs. existing housing has an adverse impact on the market for new homes and homebuilding. The response to both of the above questions is no. Visceral opposition to the repeal of a “good loophole” such as the MID is understandable, absent a more thorough and empirical analysis of the impact of the FairTax vs. the MID on home ownership and the homebuilding industry. Such an analysis demonstrates that preserving the MID is the classic instance of a situation where the business community confuses support for particular businesses with support for enterprise in general. -

Form 1040 Page Is at IRS.Gov/Form1040; the Pub

Note: The draft you are looking for begins on the next page. Caution: DRAFT—NOT FOR FILING This is an early release draft of an IRS tax form, instructions, or publication, which the IRS is providing for your information. Do not file draft forms and do not rely on draft forms, instructions, and publications for filing. We do not release draft forms until we believe we have incorporated all changes (except when explicitly stated on this coversheet). However, unexpected issues occasionally arise, or legislation is passed—in this case, we will post a new draft of the form to alert users that changes were made to the previously posted draft. Thus, there are never any changes to the last posted draft of a form and the final revision of the form. Forms and instructions generally are subject to OMB approval before they can be officially released, so we post only drafts of them until they are approved. Drafts of instructions and publications usually have some changes before their final release. Early release drafts are at IRS.gov/DraftForms and remain there after the final release is posted at IRS.gov/LatestForms. All information about all forms, instructions, and pubs is at IRS.gov/Forms. Almost every form and publication has a page on IRS.gov with a friendly shortcut. For example, the Form 1040 page is at IRS.gov/Form1040; the Pub. 501 page is at IRS.gov/Pub501; the Form W-4 page is at IRS.gov/W4; and the Schedule A (Form 1040/SR) page is at IRS.gov/ScheduleA. -

UBS Financial Services Inc

Ratings: Moody’s: “Aa1” Standard & Poor’s: “AAA” Fitch: “AAA” (See “RATINGS” herein) OFFICIAL STATEMENT Dated: April 19, 2011 NEW ISSUE: BOOK-ENTRY-ONLY In the opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Bonds is excludable from gross income for purposes of federal income taxation under existing law, subject to the matters described under “TAX MATTERS-Tax Exemption” herein, including the alternative minimum tax on corporations. $15,000,000 CITY OF CARROLLTON, TEXAS (Dallas, Denton and Collin Counties) GENERAL OBLIGATION IMPROVEMENT BONDS, SERIES 2011 Dated: April 15, 2011 Due: August 15, as shown below Interest on the $15,000,000 City of Carrollton, Texas, General Obligation Improvement Bonds, Series 2011 (the “Bonds”), will be payable August 15 and February 15 of each year, commencing August 15, 2011 until maturity or prior redemption. The Bonds will be issued only in fully registered form in any integral multiple of $5,000 of principal amount, for any one maturity. Principal of the Bonds will be payable to the registered owner at maturity or prior redemption upon their presentation and surrender to the Paying Agent/Registrar (the “Paying Agent/Registrar”), initially U.S. Bank N.A.. Interest on the Bonds will be payable, by check, dated as of the interest payment date, and mailed first class, postage prepaid, by the Paying Agent/Registrar to the registered owners as shown on the records of the Paying Agent/Registrar on the Record Date (see “Record Date for Interest Payment” herein), or by such other method, acceptable to the Paying Agent/Registrar, requested by, and at the risk and expense of, the registered owner. -

![[REG-107100-00] RIN 1545-AY26 Disallowance of De](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2433/reg-107100-00-rin-1545-ay26-disallowance-of-de-1222433.webp)

[REG-107100-00] RIN 1545-AY26 Disallowance of De

[4830-01-p] DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY Internal Revenue Service 26 CFR Part 1 [REG-107100-00] RIN 1545-AY26 Disallowance of Deductions and Credits for Failure to File Timely Return AGENCY: Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Treasury. ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking by cross-reference to temporary regulations and notice of public hearing. SUMMARY: This document contains proposed regulations relating to the disallowance of deductions and credits for nonresident alien individuals and foreign corporations that fail to file a timely U.S. income tax return. The current regulations permit nonresident aliens and foreign corporations the benefit of deductions and credits only if they timely file a U.S. income tax return in accordance with subtitle F of the Internal Revenue Code, unless the Commissioner waives the filing deadlines. The temporary regulations revise the waiver standard. The text of the temporary regulations on this subject in this issue of the Federal Register also serves as the text of these proposed regulations set forth in this cross-referenced notice of proposed rulemaking. This document also provides notice of a public hearing on these proposed regulations. DATES: Written comments must be received by April 29, 2002. Requests to speak and outlines of topics to be discussed at the public hearing scheduled for June 3, 2002, at 10 a.m. must be received by May 13, 2002. ADDRESSES: Send submissions to: CC:ITA:RU (REG-107100-00), room 5226, Internal -2- Revenue Service, POB 7604, Ben Franklin Station, Washington, DC 20044. Submissions may be hand delivered Monday through Friday between the hours of 8 a.m. -

Comparing Average and Marginal Tax Rates Under the Fairtax and the Current System of Federal Taxation

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES COMPARING AVERAGE AND MARGINAL TAX RATES UNDER THE FAIRTAX AND THE CURRENT SYSTEM OF FEDERAL TAXATION Laurence J. Kotlikoff David Rapson Working Paper 11831 http://www.nber.org/papers/w11831 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 2005 © 2005 by Laurence J. Kotlikoff and David Rapson. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Comparing Average and Marginal Tax Rates Under the FairTax and the Current System of Federal Taxation Laurence J. Kotlikoff and David Rapson NBER Working Paper No. 11831 December 2005, Revised November 2006 JEL No. H2 ABSTRACT This paper compares marginal and average tax rates on working and saving under our current federal tax system with those that would arise under a federal retail sales tax, specifically the FairTax. The FairTax would replace the personal income, corporate income, payroll, and estate and gift taxes with a 23 percent effective retail sales tax plus a progressive rebate. The 23 percent rate generates more revenue than the taxes it replaces, but the rebate's cost necessitates scaling back non-Social Security expenditures to their 2000 share of GDP. The FairTax's effective marginal tax on labor supply is 23 percent. Its effective marginal tax on saving is zero. In contrast, for the stylized working households considered here, current effective marginal labor taxes are higher or much higher than 23 percent. Take our stylized 45 year-old, married couple earning $35,000 per year with two children.